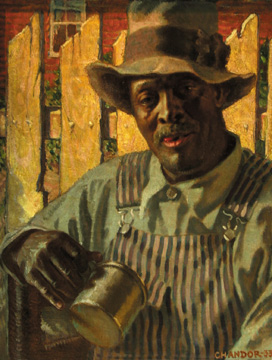

“That’s the Mona Lisa of Texas art,” A.C. Cook said, motioning toward one of the numerous canvases hanging in The Bull Ring, his Stockyards ice cream parlor — and art museum.

“That’s the Mona Lisa of Texas art,” A.C. Cook said, motioning toward one of the numerous canvases hanging in The Bull Ring, his Stockyards ice cream parlor — and art museum.

Cook, a scholar and collector of pre-1950 Texas artists, owns many paintings but none more dear than the portrait of Alphonse Harrison.

It might surprise some to know that cowboys and Indians don’t define what’s referred to as early Texas art. Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington created Western paintings and sculptures that enthralled Fort Worth Star-Telegram owner Amon Carter, who made sure that countless Fort Worth residents could marvel at the action-packed images for decades to come. But as great as those artists were, Russell (of Montana) and Remington (New York) weren’t representative of early Texas art, at least not the genre that’s prompting fevered attention among collectors and museum curators these days.

“For many decades, Texas art was considered an oxymoron; if it was good fine art it couldn’t have been made in Texas,” said Ted Pillsbury, a former director of the Kimbell Art Museum who is now helping Houston’s Heritage Galleries prepare for an early Texas art show.

Texas artists were as scarce as pearly white teeth in the 1800s. The state was wild and hard, and most people focused on survival. Art from the era leaned toward the historical, as mapmakers, illustrators, and painters documented the Mexican War, Indian skirmishes, and the local geography. Robert Onderdonk’s painting of Davy Crockett wielding his rifle as a club at the Alamo is among the most famous, even though it was born more of imagination than fact. These highly valued historical paintings now hang in museums, government buildings, and private collections.

Texas artists were as scarce as pearly white teeth in the 1800s. The state was wild and hard, and most people focused on survival. Art from the era leaned toward the historical, as mapmakers, illustrators, and painters documented the Mexican War, Indian skirmishes, and the local geography. Robert Onderdonk’s painting of Davy Crockett wielding his rifle as a club at the Alamo is among the most famous, even though it was born more of imagination than fact. These highly valued historical paintings now hang in museums, government buildings, and private collections.

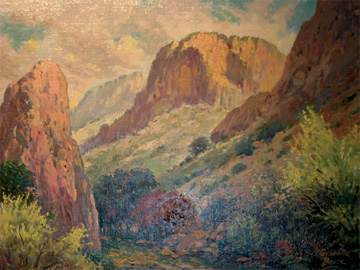

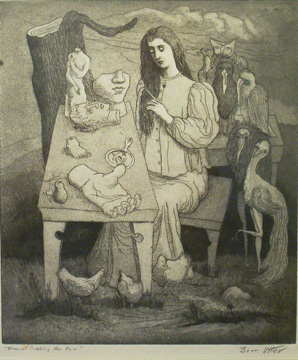

By the end of the 1800s, many Texas artists were leaving the state to study abroad or in New York and Chicago and then returning here to paint. This art reflected the state’s hardscrabble but gorgeous landscapes and the lives of common folks: Julian Onderdonk’s bluebonnet-splashed pastures, Sallie Mummert’s ranch and town landscapes, Kathleen Blackshear’s stylized homage to African-American women, Everett Gee Jackson’s working families, Bror Utter’s gentle watercolors and modernist creations, Porfirio Salinas’ impressionistic scenes of cactus and scrub oaks.

Despite an influx of talented artists between 1900 and 1950, most were ignored in East Coast and international art circles. Heck, they were ignored here at home — few of them made a living from painting. They came from all walks of life but were often homemakers, women who sought professional training at art schools and had their paintings placed in exhibits and galleries but were virtually unknown outside the narrow confines of the Texas art world. Included in that world was a group called the Fort Worth Circle, who brought a whole new style of painting to Cowtown in the 1940s and 1950s.

Their art, however, isn’t a secret any longer, and a spate of exhibits being planned across the state in the next few months will introduce early Texas painters to an even wider audience. Museum curators in Fort Worth, Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, and points in between are gathering this artwork for upcoming shows. At the same time, reference books published in recent years are providing information on once-obscure Texas artists. Collectors are buying, selling, and trading in a frenzy.

“The more people see early Texas art, the more they see how wonderful and valid it really is,” said Carter Bowden, a Fort Worth arts and antiques dealer. “The market is increasing, the prices are going up, the best things are getting harder and harder to find, meaning people are holding on to them and looking for them. It’s going to get stronger and stronger.”

Cook is in demand for his knowledge of the state’s artists, taking frequent calls from collectors, loaning his artworks to curators, speaking at colleges, and giving impromptu Bull Ring tours to startled customers who walk into a Stockyards ice cream parlor only to find the walls covered in fine art.

Most impressive of all Cook’s paintings, perhaps, is Douglas Chandor’s portrait of Alphonse Harrison, his gardener. The English-born Chandor was world-renowned in the early 20th century. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Queen Elizabeth II, and Winston Churchill posed for him. He painted socialites and tycoons. So some people were surprised when one of the greatest portrait artists of his time married a Weatherford girl, settled west of Fort Worth, and designed and built a world-quality garden that is still drawing raves from visitors.

“That garden was the love of his life,” recalled former Speaker of the House Jim Wright, who was Weatherford’s mayor from 1949 to 1954.

Chandor might have been a blueblood, but he didn’t mind getting his hands dirty. As he worked on Chandor Gardens, he became close friends with Harrison. “He had a fondness for Alphonse, carrying rocks and other mundane things that had to be done,” Wright said.

Chandor might have been a blueblood, but he didn’t mind getting his hands dirty. As he worked on Chandor Gardens, he became close friends with Harrison. “He had a fondness for Alphonse, carrying rocks and other mundane things that had to be done,” Wright said.

It was 73 years ago that Chandor painted Harrison and hung the portrait above his fireplace mantel. “It wasn’t fashionable for an artist to paint a magnificent portrait of a black man, especially an artist who’d been painting FDR and FDR’s wife,” Cook said. “To most people, these were stoop-labor cotton pickers who couldn’t drink from water fountains or use the same restrooms. Then, to hang it in his own home! A lot of people are too young and don’t remember when black and white people didn’t get along. If you don’t understand what it meant, it’s just a portrait of a black guy. But if you understand the situation and the times, then you understand what this painting represents.”

The painting, like much of the work produced here after 1900, represents the rich but unromanticized art of the state’s history, its “back stories” of hard work and diverse cultures, and breathtaking, back-breaking terrains that ranged from dry buttes to Piney Woods and coastal plains.

Of course, while these gems were being painted, most art collectors weren’t paying attention. They were seeking European and East Coast art. Texans relied on Big Apple art snobs to tell them what to buy, and their own homegrown painters were viewed as little more than primitive folk artists. Even after California and New Mexico saw their regional art catch on nationally, Texas languished.

Of course, while these gems were being painted, most art collectors weren’t paying attention. They were seeking European and East Coast art. Texans relied on Big Apple art snobs to tell them what to buy, and their own homegrown painters were viewed as little more than primitive folk artists. Even after California and New Mexico saw their regional art catch on nationally, Texas languished.

A man noted for helping turn the tide is Fort Worth’s own David Dike. Twenty years ago, he was among the first to anticipate a growing interest in Texas art. He opened a gallery in Dallas and began buying pieces by overlooked artists. Today, his annual auctions — held the third Saturday in October at his gallery — are legendary. Ten years ago, the auction generated $200,000 in sales; last year’s offerings fetched $1.7 million.

“David really sensed that there might be a market here for early Texas work and went after it,” local collector Scott Barker said. “He’s reaping the rewards now for sensing that something was there. He [created] the auction market for early Texas paintings. His annual auction has become a highly anticipated event. That’s been a big factor in spreading the word.”

“David really sensed that there might be a market here for early Texas work and went after it,” local collector Scott Barker said. “He’s reaping the rewards now for sensing that something was there. He [created] the auction market for early Texas paintings. His annual auction has become a highly anticipated event. That’s been a big factor in spreading the word.”

Another impetus was attention from politicians such as Tom Delay, Bob Bullock, and George W. Bush, who hung Texas art in the state capitol. Currently, Bush has three Onderdonk paintings in the Oval Office to remind him of his home state. Also hanging there are a Tom Lea image of West Texas and a painting by Frank Reaugh of a cattle herd.

Major museums and institutions legitimize art through their exhibits, and early Texas art is climbing steadily in the eyes of those experts. The coming years are expected to cement that interest, aided greatly by the influx of reference books, such as the Dictionary of Texas Artists, 1800-1945 by Paula and Michael Grauer, which came out in 1999.

Texas Painters, Sculptors and Graphic Artists by John and Deborah Powers — a book that experts refer to simply as “Powers” — was published in 2000 and became a bible to collectors. “Listed” artists who received formal training and displayed their work in juried exhibitions are included, providing valuable insight to those pursuing and purchasing the genre.

Texas Painters, Sculptors and Graphic Artists by John and Deborah Powers — a book that experts refer to simply as “Powers” — was published in 2000 and became a bible to collectors. “Listed” artists who received formal training and displayed their work in juried exhibitions are included, providing valuable insight to those pursuing and purchasing the genre.

“Information is the key to the whole thing, and if you have the information at hand, you can be a successful collector,” Barker said. “Without information you’re just shooting in the dark. Ten years from now there will a lot more information than there is now. That’s why I think this thing is going to continue to grow.”

Many of the painters in the genre have either died or are nearing the end of their lives. In the art world, time and death offer perspective, and some of those once-overlooked artists are now being lionized. Add in the effect of eBay, where buying a painting is as easy as pushing a button, and early Texas art appears poised for an explosion of interest. Works by first-tier artists are already out of reach for any but the wealthy. Last year at Dike’s auction, an Onderdonk bluebonnet painting went for $138,000. Even a little pastel by Reaugh brought three times the expected $6,000 selling price.

“People are waking up and wanting to collect what they should have been collecting all along — their own artists,” Cook said. “There is a lot of good Texas art in the second, third, and fourth tiers, thank goodness. We can still collect good art.”

“People are waking up and wanting to collect what they should have been collecting all along — their own artists,” Cook said. “There is a lot of good Texas art in the second, third, and fourth tiers, thank goodness. We can still collect good art.”

Works by talented but obscure artists remain abundant, although many of these artists won’t be considered obscure forever. And while landscapes remain a fixture of the genre, early Fort Worth artists who introduced modernism to locals are among those gaining acclaim (Bror Utter, Dickson Reeder, Bill Bomar, Kelly Fearing, David Brownlow, Marjorie Lee, Olive Pemberton, and many others).

“The Fort Worth Circle artists are a bargain now,” Dike said. “They were very cutting edge and avant garde for their day.”

Barker for years has considered compiling and publishing a dictionary of Fort Worth artists, and Cook is convinced the book would sell well. Reference books about artists usually increase interest in — and prices for — their work.

As for which painting is Texas’ answer to the Mona Lisa, collectors and dealers have their own opinions. Dike described Chandor’s portrait of Harrison as a “very important piece of art” but said Dallas artist Tom Stell’s self-portrait, done during the Depression, was most comparable. And, yes, there is an interesting backstory to the Stell portrait, as with many of Texas’ best artworks.

“It was lost for 80 years, and this doctor in San Antonio ended up finding it and buying it,” Dike said.

The quality of Texas art and its homage to history, combined with the collector’s desire for conquest and profit, keep enthusiasts such as Wally DeRoeck on the lookout for new acquisitions. DeRoeck owns golf courses around the state and often visits Dike’s gallery when he’s in town. On a recent afternoon, he stopped in to find more art for his home and office in Austin.

“I love the detail, the light,” he said, looking at a large landscape by Harold Roney of San Antonio, who had somehow captured the brilliance of sunrise with nothing but oil paint. “I don’t like dark paintings. I’m a happy guy.”

Thirty minutes later, he had purchased the Roney and four other paintings for about $30,000.

Increasing demand and rising prices foreshadow things to come, Pillsbury said. “In the next 10 years, the interest in early Texas art will kind of move from an antiquarian level and get broader recognition as a significant movement,” he said. “There is a growing recognition that some of these artists are of tremendous significance.”

You can reach Jeff Prince at Jeff.Prince@fwweekly.com.