A devout blues lover on his way through Texas to track down Houstonian Lightnin’ Hopkins, Strachwitz asked them if they knew of any surviving local bluesmen — they didn’t say much, probably out of fear that the white dude with the funny accent was a bill collector or cop. But after a few minutes of chat one of the guys mentioned a name, “Black Ace.” Strachwitz remembered the name from a list he’d been sent by another blues aficionado. He asked where he could find him. “At five o’clock at that tavern there,” one of the guys said, pointing across the street to a plain, monolithic storefront. “You can’t miss him. He’s got a white shirt on that says ‘Ace’ on it.”

A devout blues lover on his way through Texas to track down Houstonian Lightnin’ Hopkins, Strachwitz asked them if they knew of any surviving local bluesmen — they didn’t say much, probably out of fear that the white dude with the funny accent was a bill collector or cop. But after a few minutes of chat one of the guys mentioned a name, “Black Ace.” Strachwitz remembered the name from a list he’d been sent by another blues aficionado. He asked where he could find him. “At five o’clock at that tavern there,” one of the guys said, pointing across the street to a plain, monolithic storefront. “You can’t miss him. He’s got a white shirt on that says ‘Ace’ on it.”

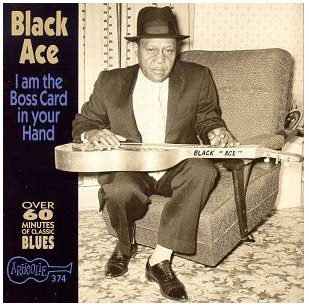

The man with “Ace” embroidered on his shirt turned out to be Babe Karo Lemon Turner, a longtime employee at a Fort Worth photography studio. Turner took Strachwitz home to the modest shotgun house he lived in on 1306 E. Jessamine St., near the Union-Pacific railroad tracks. They talked, and Ace eventually retrieved his old guitar from the attic. It was a heavy, square-necked National Style 2 Tricone Resonator with engraved flowers and busted strings. It was an artifact of acoustic amplification before Muddy Waters went electric and rendered such experiments moot. Not many of them had survived the scrap-metal drives of World War II. Strachwitz paid for fresh strings, and soon Ace had it tuned Sebastopol-style. He played it by laying it across his knees and sliding a little glass cough-syrup bottle across the frets. The sounds that came out, according to Strachwitz’ account, were downright eerie: “I am the Black Ace, the boss card in your hand / And I’ll play for you, woman / If you’ll, please, let me be your man.”

From 1936 until 1941, Ace performed this song, his signature number, on a weekly show on KFJZ, a 100-watt Fort Worth radio station owned by Elliot Roosevelt, FDR’s son. The song also got Ace signed by the legendary Decca label when its honchos came trawling through Texas and helped him land a small role in the seminal and now-historic “race” film, The Blood of Jesus. As Strachwitz listened, he intuited why Black Ace was a big deal to Strachwitz’ fellow blues lover, an Englishman, Paul Oliver. Ace’s style was a throwback, but it was also a living sample of recombinant blues DNA. Ace’s repertoire was part Dallas speakeasy, part raucous Louisiana roadhouse, part Delta house-party moan, part loopy Hawaiian luau. His lyrics were about the usual — wimmin trouble — often rendered in elaborate, veiled metaphors that could slide graphic sexual content right over the heads of children and toe-tapping church women and FCC goons, who all no doubt thought they were hearing songs about Santa Claus or stranded tourists. “If you’re a hitch-hikin’ woman, you can thumb a ride with me / I just had my crankcase drained, mama / My motor won’t give out on me.”

Strachwitz heard enough in Fort Worth to know that he would be coming back to record. What he didn’t know yet: His little do-it-yourself record company, Arhoolie, would someday be one of the world’s most important reservoirs of vanishing vintage blues. And the Englishman Oliver would soon be one of the world’s experts on American blues. All Strachwitz really knew was that Ace’s music was outsider art that shouldn’t be allowed to die. Thus the young Californian began his life’s work, tracking names that were once mighty in the blues world: not only Lightnin’ Hopkins and Black Ace but Mance Lipscomb, Alex Moore, Big Mama Thornton, Joe Callicott, Fred McDowell, Bukka White, and Big Joe Turner. A lot of the songs that Strachwitz recorded would be covered by such diverse talents as Janis Joplin, The Rolling Stones, and Alan Jackson. But none by Black Ace. At least not yet.

Originally issued on vinyl in 1961, I Am The Boss Card in Your Hand is now being re-released in CD form by Arhoolie. It contains 17 songs, all recorded in Ace’s living room, as well as the six sides he recorded for Decca in Chicago in 1937. Aside from a couple of un-issued recordings done for Vocalion in Dallas (most likely in the same warehouse at 508 Park Ave. that Robert Johnson recorded in), I Am the Boss Card represents Black Ace’s entire recorded oeuvre. I Am the Boss Card is a handy little piece of intelligence, useful in the normal human quest to “keep it real.” Ace’s music comes from an old wellspring: hard-scrabble rural beginning in Hughes Springs, Texas, singing in the church choir, and a homemade first guitar as good as a ticket on a passenger train to a better place — even if that place was the sweet, rough, ice-pick circuit of turpentine camps and juke joints in East Texas and West Louisiana, and, eventually, the more urbane but equally dangerous Shreveport. Black Ace was 30 when he recorded his 78’s, and these are the cuts to listen to first. In the original Deccas, the Resonator is dazzling: all bright, tight spangles of laconic slide, mortared together with that ’30s tempo where foxtrot meets mule-clop. In “Triflin’ Woman,” the words bite a little, sort of like Johnson’s:

I want you to get up in the morning, woman,

And try to find yourself a job

Stop sitting’ around here tellin’ me, baby,

’Bout the times bein’ hard

Don’t you ride no streetcar, mama

You must walk all over town

And you must find yourself a job, woman,

Before the evenin’ sun goes down

In the version that Strachwitz captured decades later, the guitar chops are not as stellar, and the words don’t bite anymore. They soothe and encourage in a way that the slightly nihilistic Johnson eschewed. This places Ace among the great blues survivors, like Bill Broonzy or John Lee Hooker. That’s the key difference between the old cuts and the newer ones: what the man lived long enough to learn. In the later work, Ace’s voice is a deeply expressive instrument, informed by decades of survival and of trying to understand women. He knew what it meant to have to set aside your aspirations for someone or something else. In 1943, Ace had to give up music and serve an entity he always referred to as “Uncle Sam,” only to find himself unemployable afterward. Ace worked the cotton fields again, then mopped floors for several years at Meacham Field (now Meacham International Airport) before being laid off in 1955. After that, he landed steady work at Don Juarez, the photography studio.

One of Ace’s songs is about as frank an admission of male vulnerability as has been uttered by a musician anywhere: “I’ve been in love with you, baby, ever since the day I was born / You found out that I love you / Now, please be kind to me.” Other songs are simply instrumental “stomps” or “breakdowns” that veer off into deliberate atonal experiments that still fascinate blues purists and that sound now like an ancestor of thrash. Black Ace’s last public performance was in the 1962 Sam Charters documentary The Blues, two clips of which are available on YouTube. Ace passed away in 1972 and is buried in Malakoff, a small town about 50 miles southwest of Tyler. There’s a historical marker where he rests. Perhaps another one should be installed at the corner of Beverly and East Jessamine in Stop Six, where Black Ace recorded his songs for Chris Strachwitz.

Like much of the roots music revisited on porches and in juke joints from Navasota to Detroit, Ace’s creations still have the power to astound, mainly in their stark outsider’s integrity. It’s like studying your own birthright, to hear Arhoolie’s canon of songs from some of America’s janitors, grass-cutters, and gas station attendants who agreed to put their shoulder to the same old wheel that cast them off decades earlier and who did it with such grace and well-documented lack of bitterness.

Black Ace’s songs are all here for the taking, not only for that small die-hard cadre of blues hobbyists but also for some smart and enterprising young guitarist somewhere. The songs on I Am the Boss Card in Your Hand are ripe for the covering.