Mace Maben hadn’t sung in a year when he got a call to join his friends Eddie Miller and the Heavy Hitters onstage at the now-defunct Ridglea Jazz Café. There wasn’t much anguish in the decision to take the offer — it wasn’t his gig, after all, and the time seemed right.

But word got out.

“The house was packed with all of our friends,” Mace’s wife Suzie recalled. And the excitement among them was palpable.

Here was Mace, nearing 59, beginning the last reinvention of his career. Starting over is something he’d been doing effortlessly since he was a teenager. But in August 2010, the renewal had been fundamental: He’d had to change everything from the sort of musical mnemonic devices that had become second nature to the gauge of his strings, now far lighter to accommodate a new sensitivity in his fingers.

“I’m used to using 11s, and I had cut down to 9s — that’s what the heavy-metal kids play!” he explained with a laugh.

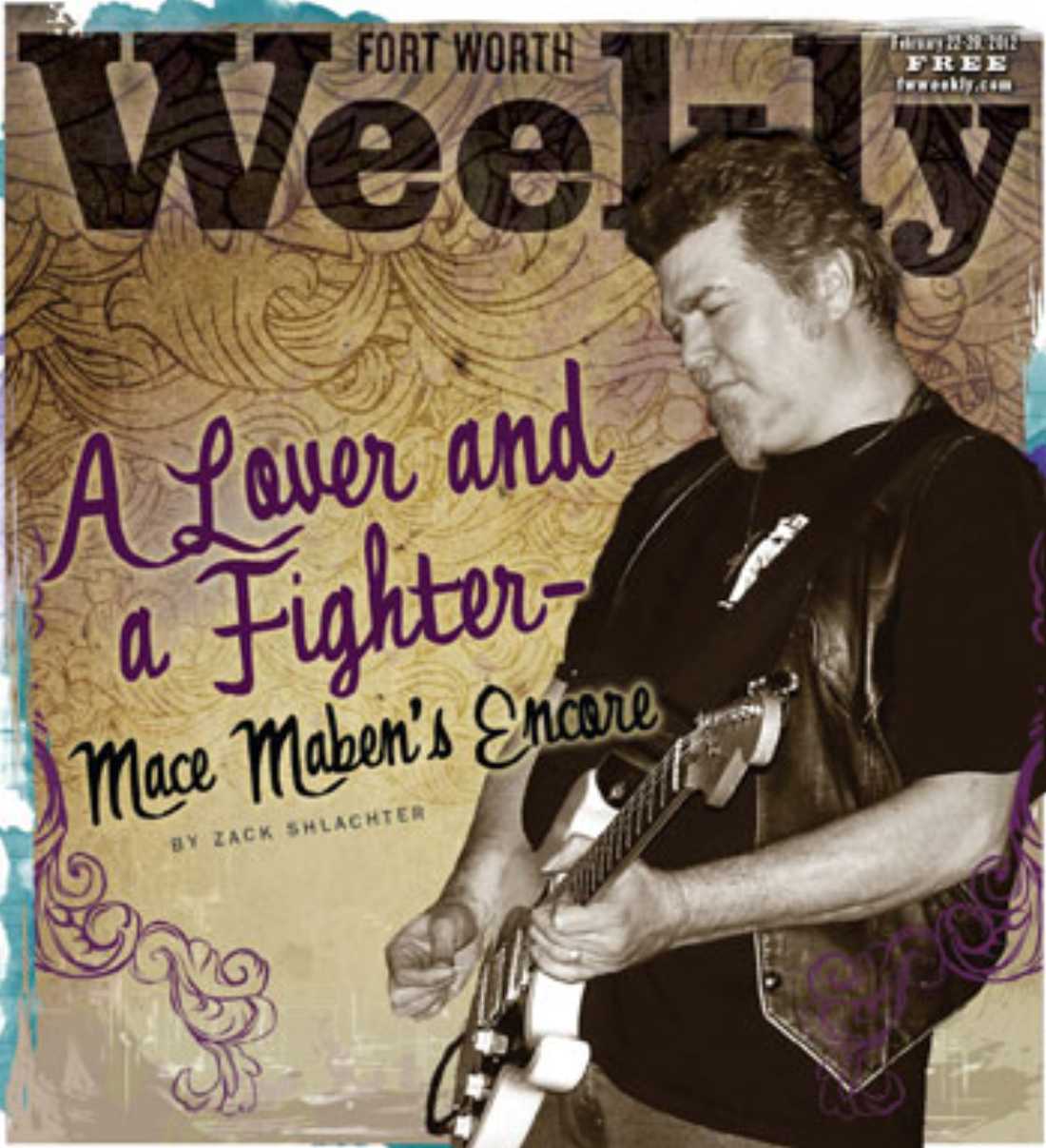

Friends from all the stages of his life, beginning with his days in Fort Worth’s teen pop scene, turned out. Mace has played all over the country, fronted several different bands, opened for many of his heroes. In his day, he was as big a rock star as Fort Worth ever produced, the real article from mop-top cutie to hard-rock sex god. He’s also been forced to adjust to the many disappointments in a career that didn’t go as far as he’d dreamed.

This time, though, he was coming back from lung cancer and dealing with neuropathy severe enough that he’d had to re-teach himself how to play the guitar.

But music was his life, what kept him going. So he climbed up on the stage, thinking he’d only accompany the band (itself accompanied by karaoke-like instrumental tracks) for a few numbers.

“He ended up singing the whole night,” said Suzie.

His confidence surging, Mace dedicated the first song to Suzie, who’d been with him in the years after the heyday and had taken care of him when everything changed. She hadn’t known whether he would even be able to sing again until he got on stage that night — he’d simply told her not to worry.

For that momentous occasion, he chose a Sam Cooke classic and crooned to her, “Darling, you send me / I know you send me / Darling, you send me / Honest you do.”

“I bawled,” Suzie said.

This was going to be a story about Mace Maben’s greatest comeback. After the success at the Jazz Café, he resumed a residency at the Keys Lounge starting in October 2010 that lasted, off and on, until this past December. An oldies/blues bar tucked into a nondescript shopping center in southwest Fort Worth, the Keys was a familiar place for Mace to settle into for this newest incarnation of his career. His band consisted of a rotating crew of friends.

In February 2011, the cancer resurfaced in Mace’s lymph nodes, but he decided to forgo any further treatment. The doctors gave him eight months. He kept playing, and though he stayed ahead of it for almost another year, he knew his swan song wouldn’t last indefinitely.

On Christmas Eve last year, he suffered a major fall in his kitchen. On the way down, he hit the corner of a microwave oven, breaking his jaw so severely that it required extensive — and creative — surgery. Because he was prone to pneumonia due to the cancer, the surgeons couldn’t wire his mouth shut, opting instead for bands that stayed on for a month.

Forget singing. Mace’s food intake dropped and, with it, his energy. Meanwhile the cancer has continued to spread, and now there’s a different last verse to the story of his life in music.

********

When Suzie dragged Mace to the doctor in September 2009, she had no inkling of a problem with his lungs.

“We went to the hospital because I was constipated,” Mace said in an interview in early December.

Since the condition had been persistent, the doctor ordered an X-ray. Standard procedure. But the technician mistakenly scanned Mace’s chest instead of his abdomen. And that’s when he and Suzie got the shock of their lives: The X-ray revealed a tumor two to three inches long lodged in his upper-right lung.

But if the revelation felt like a cruel bait-and-switch, they didn’t have time to contemplate it.

“The doctor said you have to get back here — seven o’clock in the morning,” Suzie said. “We walked in the door, and he said, ‘I was gonna give you two more minutes, and then I was gonna come and get you.’ I said, ‘What’s going on?’ That’s when all hell broke loose.”

The radiologist had confirmed what the doctors had initially suspected, that Mace had small-cell lung cancer. According to the National Cancer Institute, small-cell lung cancer is fast-growing, starting in lung tissue before spreading to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes and brain. A lifelong smoker, Mace had been susceptible to the disease. “They gave him two months when they first examined him,” recalled Mace’s brother Garry.

Deciding against surgery, the doctors suggested aggressive chemotherapy and radiation. Mace underwent radiation daily for seven weeks and simultaneously did chemo — a three-day ordeal every two and a half weeks, four times.

“Every time he did a round of chemo,” Suzie said, “it kicked his ass.”

“It is the worst thing I’ve ever been through,” Mace admitted. And though Suzie would joke that Mace was an awful patient (he tried to leave the hospital a couple of times, ripping out his IV, which would invariably lengthen his stay), eventually he accepted his condition and the treatment.

“I took him to his radiation and chemo treatments,” said Garry Maben. “He had 48 radiation treatments. It’s brutal. He never complained, never one word. We’d get back in the car and start sharing stories about our parents, stop at the convenience store for a lotto ticket and a Big Red, and go home.”

While some of the radiation was preventive, to keep the cancer from metastasizing to his brain, the treatment took its toll on Mace’s short-term memory. And the chemotherapy and radiation caused damage to his nerves, known as neuropathy, resulting in numbness and burning in his legs and hands — a guitarist’s nightmare.

Other folks might have folded up the musician tent right there. But Mace just went back to learn all over again the skills he’d built his life on.

********

Mace Maben’s musical education started at home. “We were pretty wealthy at one time,” he explained. “We had a huge music room, with a Hammond organ and a piano back-to-back and a set of drums.” Mace’s mother was a concert pianist. His father, the owner of a floral business, played the organ; his oldest brother Minton played vibes and keys, while older brother Garry sat behind the drum set.

Mace started on piano and, as a choir boy, took voice lessons. Then, around age 12, he took up the guitar. As the youngest member of the family, this was a surefire way to stand out.

“He wasn’t as effervescent as I was as a kid,” said Garry, now 69. “I was always more outgoing, but when Mace hit his stride playing guitar, then he really lit up. It sparked an inner talent that he wouldn’t have had otherwise.”

Along with thousands of other teens across the country, Mace picked up his guitar in the wake of The Beatles and the British invasion. But his first band, the Viscounts, seemed to have an advantage, courtesy of their well-to-do parents. “A bunch of kids in the neighborhood just got together and started playing,” he recalled. “So our parents hired us a manager — a British guy, Alexander Everett.” The manager’s day job? Teaching Latin at the nascent Fort Worth Country Day School.

Despite having their own personal Brian Epstein, the Viscounts never took off. A few years later, Mace formed the band Courtship and had his first real shot at stardom. Fashioning their hair into mop-tops and donning suits, the band had a look and sound that still landed in the poppier end of the musical spectrum. The group would eventually relocate to Los Angeles in pursuit of a record deal, but first it left a mark on Fort Worth’s teen scene.

If The Beatles had Hamburg, Mace and his bandmates had The Cellar. In an interview for Giles McCrary’s forthcoming documentary about the famous downtown club, Mace recalled that Courtship held a residency there, turning out sets from 7:30 p.m. to midnight five nights a week for weeks at a time. (Then they’d scurry to the Eastside Club on Belknap and play for another five hours or so.)

In the two years that McCrary has been working on the film, in his spare time and from his own pocket, he’s found that The Cellar wasn’t just any rock club. “It offered a training ground where [musicians] could play with and learn from others,” he wrote in the treatment for the film. “The Cellar represented one of the few places that a musician could work full time and make a living at it.”

A generation came of age at the Cellar, which from 1959 to 1972 provided Fort Worth youth an introduction to the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. At the time, this meant everything from cutting-edge music to sexual exploration, underage drinking to racial segregation. So notorious was the nightclub that it even became a footnote in history, turning up in the Warren Commission Report on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. (The night before Kennedy was shot in Dallas, members of his Secret Service entourage had partied at The Cellar. There’s no conspiracy theory, McCrary clarified, just an interesting connection.)

The Cellar’s status as a rock ’n’ roll outpost where Fort Worth teens participated in the social transformations of the 1960s also dovetailed with a distinctly local history. “There’s a direct line from Hell’s Half Acre to the Jacksboro Highway to The Cellar,” said McCrary in an interview last month at his home studio. “It was the last vestige of ‘wild’ Fort Worth — and Mace was in the middle of all that.”

“It changed my life,” Mace says in the film. “I found out there that I could be a real, honest outlaw — and still stay out of jail.”

Performing also confirmed for him that music was his calling. The next logical step was to shoot for a record deal, and that meant the band would have to move to L.A. Back then,“You had to be on a major label,” Mace explained. “Now you don’t. Guess I was behind my time or ahead of my time.”

When the band made the move, Mace was only 17 and a year shy of graduating from Arlington Heights High School.

“I was a little ticked with my mother and father at the time,” Garry admitted. “I wanted to see him at least finish high school, but he and his band were so good, our parents just felt like that was his future.”

As the baby of the family, Mace always had the support of his parents. When he got busted for smoking pot after a Courtship show in Odessa, his dad came to the rescue. “Back in those days, you could get a 20-year sentence,” Garry said. “Dad immediately got in the car and drove to Odessa, bribed the judge, and got him off.”

“I kinda needed to get out of town ’cause I was a real bad kid,” Mace said. “I just hit the road and stayed on the road, off and on, for about eight or nine years.”

********

Courtship released one single with Capitol Records, “Comment,” but never put out an album. Though he was still a teenager, Mace didn’t romanticize the experience.

“I don’t know if ‘exciting’ is the word,” he said with a laugh. “It was a lot of work. A lot of rehearsal and writing, long days.”

At some point, Courtship morphed into a new band, Texas. The main differences were some minor personnel changes and the desire, Mace recalled (not without some eye-rolling), “to get ‘heavier.’ ”

Though Texas also tried playing the record-label game in California and toured all over the country, the group was ultimately a “big regional act,” in the words of friend Sammy Roberts. It was as a member of Texas that Mace acquired celebrity status in Fort Worth. As frontman, he set the tone for the band.

“We were rock stars,” drummer Gary Osier said plainly. “I wouldn’t go to the 7-Eleven without full makeup on. I was all velvet and corduroys and full spandex.”

By all accounts, they made an impression. Amid a relentless touring schedule, Texas held a residency of sorts at Spencer’s Corner in Fort Worth, but the club didn’t fulfill the same role for the band as The Cellar had for Courtship. This was less a training ground than the place where Mace and the group held court.

Roberts, then a bartender at the club, recalled the first time he saw Texas play at Spencer’s. Serving drinks while facing a wall of often very bad sound on a nightly basis, he was hard to impress. But when Texas showed up with a “huge truck, roadies, spotlights,” they gave off an aura of professionalism and glamour he hadn’t seen before. From the sound of the first chord, he was convinced — and changed. “It gave me a whole new appreciation for that kind of music,” he said.

Legend has it that owner Spencer Taylor engaged in and won a bidding war with a local competitor over the band — accounts vary, but drinks were surely involved — that resulted in a monthly Sunday-night slot devoted solely to Texas and paying around $2,000. While that was unheard-of in 1970s Cowtown, the group was worth it — they classed up the joint. Being there, Roberts reminisced, “was like seeing a rock ’n’ roll version of a show at the Copacabana. It was a given: There’s no place else you’d be on a Sunday night.”

If Texas was rock royalty in Fort Worth, Mace was the undisputed king. “He was like a totem pole in the middle of the band,” Roberts said. “He never really had to try.” His status, however, didn’t come from showy guitar playing or an in-your-face stage presence. Instead, Mace had an effortless, indescribable swagger — and an irresistible pull, from his half-glam, half-hard rock aesthetic to his technique as a performer.

“There was a lot of ‘come hither’ in his music,” said Jerry Shiffman, a longtime friend and former business partner. “The way the chords would draw you in — and then release … .”

Elizabeth Macey caught her first Texas performance in Oklahoma City as a high-schooler, where she was visiting a friend. She and Mace were instantly drawn to each other and began talking — et cetera — after Texas’ set.

“There was nobody else in the room,” she recalled. “There was, of course, but not to me.” She went back home to Houston and that was that. Or so she thought. A couple of years later, listening to her car radio, she heard a DJ mention an upcoming Texas show at Whiskey River. “I turned up the volume and freaked out,” she said. She went to the concert and reconnected with Mace. After a couple years of dating casually, she moved to Fort Worth to be with him.

“I grew up with him,” Macey said. Having come from a single-parent household, the responsibility had fallen to Macey to raise herself and her younger brother, and much of her youth was spent running wild. She’d made a second home at rock shows. In Fort Worth, that behavior became a lifestyle for a while.

“After every show, it was ‘party at Elizabeth and Mace’s house,’ ” she said.

Life gradually settled down, and the couple stayed together for 16 years. Elizabeth wanted kids, Mace didn’t, and eventually they split amicably. (And neither wound up having children.)

Reflecting the frequent intersection of love, friendship, and work that defined Mace’s life, in the early years of their relationship he and Elizabeth labored together for several years at This is the Pits, a recording studio he started with Shiffman.

Located at the corner of West Allen and Fairmount avenues in a former grocery store, the recording studio operated from 1979 to 1985, well before Fairmount became the artists’ enclave it is today. Shiffman and Mace were pioneers of adaptive re-use. “I still remember the dairy cases — like walk-in coolers,” Shiffman said. “We turned them into echo chambers for recording.”

Shiffman had first seen Mace play with Courtship in 1967 at the Eastside Club, but the two didn’t link up until the ’70s. Shiffman wanted to start a recording studio with Mace for two reasons. “I wanted to provide a vehicle for him to create and to further his art form,” he said. And in turn, “Mace showed me the stuff that makes music.” Mace was the producer and in-house session musician, Shiffman ran the business while learning audio engineering under Mace, and Elizabeth was Shiffman’s secretary.

Though the studio didn’t last, Mace would increasingly shift his efforts away from clawing for a foothold in the mainstream music world. Texas had had several false starts over the years, beginning with Motown when the legendary R&B label moved house to Los Angeles. As with Courtship, none of Texas’ work ever saw release on the majors, until they signed with Bell Records.

The band put out one album with Bell, the self-titled Texas, in 1973. “The label spent half a million to promote the record, and it was selling like hotcakes in the first six weeks,” said Garry. By 1974, however, “Bell went into receivership, and Mace never got the rights to his music back.”

Other chances would come and go. “We came right to the edge — we were 20 minutes from it,” Osier said. He said Texas lost a contract with Elektra in 1977 — and it went to The Cars instead. That detail is telling: the Boston-based five-piece was at the forefront of New Wave music. Texas, by contrast, was still dealing in a bluesy hard rock with a pop sensibility, a mode whose time in the mainstream spotlight had largely passed.

But if Texas was ultimately a bar band, it also did things differently. The wall of sound that had so impressed Sammy Roberts wasn’t so much the lush instrumentation associated with Phil Spector as something that filled the space in bars like nothing before.

“We took arena-level sound — a Stevie Wonder or Steely Dan level of sound — and took it into clubs,” said Osier. “We found arena horns and learned how to use them in clubs. Sound system-wise, we took all this club bullshit to another level. Among the musicians and the art people, we were renowned.”

Neither Mace nor Osier can recall when Texas finally broke up; after too many rotten deals and missed chances, the band just petered out. “We just got tired of beating our heads up against the wall,” Mace explained. “There comes a point when there’s only so much you can do, and you gotta make a change.”

By the 1980s, Mace was playing more and more on his own. He wrote a song with Christopher Cross, “Deal ’Em Again,” which appeared on Cross’ 1983 album, Another Page. “I tried to use that to help the studio,” Shiffman recalled, “but I didn’t know how to sell the package.”

Trying his hand at business outside the music industry, Mace was a silent partner in a restaurant on Eagle Mountain Lake. But when lake levels dropped during a particularly bad drought, the restaurant was cut off from the boaters who were its customers, and the place shut down. Meanwhile, the Maben family’s fortunes reversed when their floral business closed in the mid-1980s.

“You deal with things because you have to,” Osier reflected. “I consider it to have been an education.” He eventually quit playing music but didn’t quit the biz, becoming a talent buyer for venues like Billy Bob’s and WinStar Casinos.

That’s how Mace saw it too. “Especially when you start as young as I did, you can get bitter real, real soon,” he said.

Many of Mace’s closest friends from bands and venues eventually found other full-time work. Those who still play do so on the side, for fun. Though he dabbled in business, Mace would always be a musician first. Besides, he said, “I had to keep playing to pay the bills.”

********

Naturally, it was through music that Mace met Suzie, a singer, in 1991. They were introduced via one of Mace’s bandmates and quickly began dating.

“By ’93, he’d decided to [leave that band and] do his own thing,” she recalled. “He said, ‘I want you to come with me.’ ”

In the mid-1990s, a lot of Mace’s old bandmates were hanging up their instruments. Gone were the cushy gigs he could get in his 20s. “There was nothing to book around here, all the clubs had dried up,” Suzie said. “Then Lindy Wilson called [and asked Mace] to go be a show-dude.” For a while, Mace played in Wilson’s band, Lindy and the Look, performing throughout the West and the South. The band specialized in oldies, everything from big band and show tunes to the pop-rock of the ’50s through the ’70s.

Suzie had sent Mace out on one such tour, starting in Las Vegas, with her last $50. “ ‘I’ll send you some when I make some,’ you know,” she recalled him saying beforehand. One night he called her from a casino with good news:“Guess what I just did! I won $1,700!”

Ecstatic, she told him to go do it again. To her amazement, he did just that: Thirty minutes later he returned from the video-game keno machines and reported, “I just won $2,000!” He asked her if he could use the money to buy a new amp, and she agreed before insisting he send her the remainder of the money.

“But go back down and do it again — I know you can do it,” she told him. “He calls me 30 minutes later. Son of a bitch, he won again, another $1,400. I said, ‘Now really, send it home, ’cause you’re gonna spend it all.’ And so he goes, ‘Well, why don’t you get a ticket and come out here?’ ”

“She got a plane ticket,” Mace cut in, finishing a story the two never tire of telling, “and asked, ‘Well, what are we gonna do tomorrow?’ I said, ‘We’re gonna get married.’ ”

Suzie continued to sing with Mace, but it never became a career for her. She found work as a collections manager at a law firm and became the primary breadwinner in the relationship. She likes to joke that her New Jersey origins have given her a toughness that’s helped her through everything. But those who know Suzie and Mace note the annual toy drive she organizes at Keys and the tax service she provides free of charge to friends. She’s simply a caring and devoted person.

********

When Mace’s cancer surfaced again last February, this time in his lymph nodes, he’d already spent the better part of a year recovering from the radiation and chemotherapy.

“I just said whatever God wants, God gets,” Mace recalled of his decision to forgo further treatment. “I’m not going through that crap anymore.”

The chemo and radiation had taken such a toll on him, Suzie said, “I don’t think he’d [have been] strong enough to handle it again. He had lost a hundred pounds in three months. It was different when he was first diagnosed — he had the weight on him, and he was strong.”

Mace resumed as much of his old life as he could. Suzie dismantled the protective buffer she’d kept around him for months. As soon as Mace could handle solid food and was up to seeing people again, she started hosting small dinner parties.

Centered on her famous meatloaf, and with a pajamas dress code, these Sunday night dinners became a hit. The radiation treatment had shrunk Mace’s esophagus, making it difficult for him to swallow. “When he was finally able to eat, it was cause for celebration,” Suzie said.

After that, Mace moved on to his next goal: playing music again. A couple of months after the show at Ridglea Jazz Café, Mace made his proper return, headlining at Keys Lounge. There was no venue more appropriate for the comeback.

“It was very frightening, but all my friends were there,” he said. “I knew they wouldn’t bitch if I was horrible.”

That night, Mace defied expectations — most of all his own. “I couldn’t remember shit,” he chuckled, “but I was grinding that ax.”

Certainly, his friends had all hoped he would take the stage again. But his prospects had been grim. After the initial diagnosis, “I really didn’t expect him to live,” said his brother.

Once Mace regained his strength, though, there was no doubt he’d be back. Performing gave him something he couldn’t get anywhere else. “All of us have to do it — everybody who’s a musician,” said Keys Lounge owner Danny Ross, who often joined Mace’s band on keyboards. “You want to let it out. And the whole music thing is camaraderie.”

Mace played twice weekly at Keys for the next year, taking off when health problems flared up. On Sunday nights he led a jam, fittingly called Group Therapy, and the Tuesday night slot was reserved for Mace and his band, the Mabenettes. He fronted the group on guitar and vocals, backed by Linda Waring on drums and Bobby Counts on bass. Also upfront were Suzie and friend Denise Mandell Hughes — backup singers, duet partners, and occasional leads. An informal enterprise, the lineup rotated often but always involved friends.

He’d adapted to the neuropathy and managed to sling his guitar again. “He re-taught himself how to play the guitar without having to feel the strings,” said Garry. But if the feeling was gone on one level, Mace hadn’t lost his passion for performing.

“I’d ask him, ‘What kinda voodoo do you do to make this work?’ ” recalled Shiffman.

Turning 60 last September, Mace could no longer hit all the high notes from his glory days, but lung cancer or not, his pipes were in astonishingly good condition. “I’m singing as well if not better,” he said in November, between sets. Frequent bouts of pneumonia, common among lung cancer patients, would keep him home for a couple of weeks at a time, but he kept coming back.

“He got stronger every week,” said Ross.

********

For a singer to get lung cancer and for its treatment to wreak havoc on his guitar-playing fingers — these are cruel ironies. Mace overcame them, if only for a short period. In his post-treatment tenure at Keys Lounge, his repertoire of love songs and party music mixed oldies staples with the occasional gem from his own songbook, all falling under the classic rock and pop labels. In spite of his condition, this wasn’t the blues. Not in style — and not in feeling.

Nonetheless, Mace readily admitted that cancer and the treatment were worse than anything he had ever experienced. “Nothing can prepare you for this,” Suzie said. Even when life approached its most normal, he had to take 35 to 40 pills a day.

Even when Suzie had insurance that covered his treatment, the costs were heavy. Then, almost a year ago, she lost her job — and their insurance. This coincided with the gradual deterioration in Mace’s condition, and she was always there for him.

“She has been his champion,” said Sammy Roberts. When money got tight, Suzie kept them going.

She has no idea how she did it. “It’s like pulling a rabbit out of a hat,” Suzie mused.

When Mace and Suzie couldn’t claim government benefits, Suzie found support from nonprofits such as Cancer Care Services and Community Hospice. Friends put together two benefits at Keys and one at the Capital Bar to help the Mabens with the mounting bills, medical and day-to-day. Others have given directly to them, repaying the generosity the couple has always shown their friends and the community.

It would be facile to suggest that his professional disappointments prepared Mace for the health troubles, but it’s telling that he never viewed those experiences as debilitating. Instead, he was along for the ride, wherever it took him.

At the height of his powers, this meant a rock ’n’ roll lifestyle and the chance to see life from the road as a touring musician. And for as long as he could find his way onto the stage, music gave him a creative outlet that became something of a lifeline.

“I think that playing is a big part of what has kept him alive,” said Ross. Just being able to look forward to Sunday and Tuesday, he said, must have given Mace some fuel.

Mace went into jaw surgery with pneumonia and lost more weight and energy throughout the month-long recovery when his mouth was banded shut. Shortly thereafter, Suzie and Mace called in hospice care to their home, mainly to handle his medications. The hospice team has concluded that his cancer has spread further, likely to his brain.

Though Mace can no longer perform, personal connections he’d made during a lifetime of music still sustain him. From the benefit concerts organized by his buddies to the coterie of exes that never ceased being supportive friends, Mace had built all of these relationships on music. And none has been more important than his 15-year marriage to Suzie.

“She is the best thing that ever happened to him,” said Denise Mandell Hughes.

In late January, with little to do but wait for Mace to recover from the massive jaw surgery, he and Suzie would run through music together in their bedroom. The bands had just come off his teeth, and he had lost even more weight. The Keys gigs had come to an end, and he had only enough strength to go out for the occasional game of bingo.

The money problems continued to mount. In the midst of this, Suzie began penning a song, fittingly titled “I’m Disgusted.” She and Mace worked out the words and phrasings by singing it until they got it just right. But it’s not a plaintive blues or an angry screed. Taking its aim at city hall shenanigans instead of their personal situation, the song had the couple in stitches of laughter — providing a brief distraction but also connecting the two as they had first come together, through music.

Back in December, Suzie and Mace sat on their bed to give an interview for this story. She had been explaining his short-term memory problems but quickly brushed aside the subject to count her blessings.

“Most people don’t survive the treatment,” Suzie noted. “So he’s pretty much a miracle.”

“A fighter,” Mace offered.

“You had to do it,” she responded. “I wasn’t done with you.”

I’m so very sorry for your loss Suzie. In the 70’s I saw them in concert in Shreveport, Louisiana – TEXAS was the first band to play, although I don’t remember which band they fronted for – I absolutely remember TEXAS and a song on their album that was handed out to the audience goers (which was handed to me by Mace himself and he was a perfect polite gentleman) – the song was called Burger King Blues. That moment with stay with me forever – I was 16

I was sorry to hear of Mace’s passing. I had been a Bartender at Spencer’s in 76-77 and loved the night’s Texas would play. I was forced to throw away my Texas t-shirt sometime in 1989-90 when it was full of holes and you couldn’t make out the word anymore.

But I will always remember the way Mace would stand at the mic and look out over the crowd as he sang. It is to this day one of my fondest music memories and they always finished with “Tighten Up”