In 2014, Rick Wilkins took a gamble. Wilkins, curator of the Olden Year Musical Museum in nearby Duncanville, wanted to do something that had never been done before: transform a 150-year-old manually wound clock into an automated mechanism. “I couldn’t travel because I had to wind the clock every night,” Wilkins said. Also, the tower’s weight-driven movement had to be moved from its 30-foot perch to the ground floor. “I wanted the public to view it,” Wilkins said. “It would be unique to see a working tower mechanism at street level.”

So he thought of his old friend Bill Edwards. They had bought and traded antiques for 30 years. He knew Edwards had a high interest in clocks and had even been president of the local clock society. Someone told him Edwards had been involved in restoring a street clock in Grapevine’s Historic District after it had been run over by a garbage truck. Wilkins approached Edwards about the clock automation because, Wilkins said, Edwards was “familiar with large-format clocks.”

Edwards couldn’t refuse. “I’d never worked on a tower clock,” he recalled.

He faced a daunting challenge – devise a winding mechanism that would not block the view of the movement.

He scoured the internet. He decided to repurpose low-speed car window motors and printing press clutches for the job. He bet the window motors would be strong enough to lift the weights up the height of the tower, and the press devices would halt the motors to allow for the weights to descend, powering the movement below that controlled the dial and chimes above by cables and chains.

After the initial installation in June 2015, Edwards and crew faced one another with trepidation. The motors hauled their loads, but the pulley cables and sprockets didn’t mesh with the motors. The time and chimes didn’t synchronize either. Edwards told his crew, “We just have to keep working ’til we get it.”

They went through various redesigns and tryouts over the months ahead. They worked the early morning shift on scaffolds in the 10-square-foot tower made of brick and cast stone in miserable triple-digit summer heat. Wilkins brought in a portable fan and kept the men hydrated with bottled water. They persisted when seasons changed through subfreezing temperatures in the unheated tower.

It took more than two years of persistence to transform the hand-cranked Austro-Prussian War-era tower clock into a publicly visible self-winding mechanism. In gratitude, museum founder Homer DeFord made a five-figure donation to the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors’ local Lone Star Chapter 124. The chapter used the undesignated gift to free up monies to fund the annual NAWCC convention this year. “The gift was a very big deal,” said convention general chair John Acker.

Lone Star is hosting the first NAWCC national convention, Mavericks of Time, to be held in North Texas in 24 years this Thursday through Saturday at the Arlington Convention Center. The 73rd annual NAWCC convention will feature the largest gathering of seasoned watch and clock collectors and dealers this year. Visitors will have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to tour the most extensive show ever assembled of early 19th-century wooden- and brass-movement clocks by pioneer American clock maker Joseph Ives and attend lectures with expert horologists.

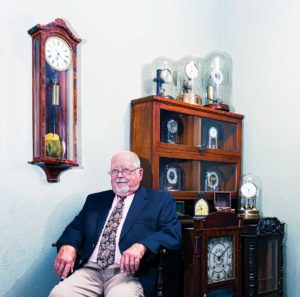

Fort Worth’s Edwards helped make this historic event happen by performing a clock-making miracle borne out of a boyhood determination to preserve cultural artifacts and an early love of complicated mechanical devices.

Bill Edwards was always a tinkerer. He grew up in a community of West Texas cotton farmers with the work ethic “Whatever breaks, you have to learn to fix it yourself.”

His father, the sole grocer in town, “never threw anything away if there was any use for it,” Edwards recalled.

As a boy, he started collecting radios before clocks for their resale value. In junior high school, he put a playing radio found in a second-hand shop in his dad’s store window by the checkout desk. In hours, it was bought by some braceros, Mexican natives brought to town under a U.S. government program to help harvest cotton. “They loved battery-run radios because they didn’t have electricity at home,” Edwards said.

From then on, when his parents went to Midland or Big Springs, Edwards begged them to bring back pawn shop radios that he could repair with the help of a local radio repairman and sell on weekends. He began collecting radios and delighted in anything that came along to see if he could “get it working.” Near high school graduation, his radio shop mentor told him, “Get an education. You don’t want to do this for the rest of your life.”

Edwards was accepted into the work-study program at Arlington State College (now the University of Texas-Arlington) as a major in electrical engineering. His studies developed his mechanical imagination evident in his ability to precisely calculate how multiple clock weights for time and chimes coordinate. “Most engineers like to work on complicated things,” Edwards said. “They are trained to appreciate how many parts work together to solve a problem.”

That engineer’s talent for synchronizing parts coupled with additional courses advanced his career. After attaining a two-year associate degree, he worked for Texas Electric Service Company owned by TX Utilities (now TXU Energy) designing power lines to Midland homes and farms. Later, after taking some computer programming courses, he transferred to the company’s computer department at the Fort Worth headquarters. During the late 1970s and early ’80s, as TESCO switched to computers for engineering studies and customer accounts, he eventually became the manager responsible for all of the company’s information technology programming. In 1984, when the newly created holding company, Texas Utilities Electric Company, merged his company with Dallas Power & Light and Texas Power & Light Company, he supervised an 80-employee department responsible for integrating the three companies’ 2.2 million customer records into one data system.

In 1990, when the company downsized, he took early retirement at 50, and the next day went to work for Electronic Data Systems (EDS), installing customer information systems all over the United States and England. His two grown sons visited him there, and his oldest, Josef, also a UTA graduate, later named his first Dallas antique mall The Gathering after a Scottish pub that he and his father frequented.

England gave Edwards the chance to purchase his first tall clock. In 1996, at the annual Midland Clock & Watch Fair in Birmingham, he discovered a “find” – a 30-hour traditional English grandfather clock with darkened walnut veneer, circa 1840. The hand-painted maker’s name – Briggs – and his hometown – Skipton, a market town in Yorkshire in Northern England – were still evident on the linen-colored dial under a scroll top. “It was an old-fashioned English clock,” Edwards said. “That’s what attracted me to it. As a child in West Texas, the only clock we had was a cheap Westclox with white background and black numbers in a metal case.”

Most importantly, his wife Karen, who listened during our telephone interviews, liked it. “If she doesn’t,” Edwards said, “it doesn’t come into our home.”

By 2000, when he returned to the United States and retired from EDS, his collecting focus had shifted from radios to clocks. He had acquired classics of early radio manufacturers like Crosley, Atwater Kent, and Grebe, but he had become disillusioned with collecting antique tube radios because of their limited time period. “The diversity and availability of collectible clocks is unlimited,” Edwards said. “It was a gradual realization there are a lot more collectible clocks out there.”

Edwards got an inside track on the antique market after his son sold The Gathering and opened up a moderately priced antique mall, Found Antiques, in the Dallas Design District in 2003, which had about 50 dealers. Since Edwards was available, he managed it.

Three years later, he did the same at the sister mall, Lost Antiques, next door, where he still has a booth. But his inside track on antiques did not produce any extraordinary finds for his clock collection.

Bill Edwards acquired his best clocks by purchasing entire collections that other collectors had assembled over decades. “The acquisitions helped finance my collection,” Edwards said. “I’d buy a few, sell a few, and keep the very best ones. It was a way to develop a collection.”

His estate purchases began in earnest in 1988 because his radio collecting had created an interest in early telegraph equipment. For $3000, he bought the entire estate of a telegraph repairman. “We ate a lot of beans that year,” Edwards said. “It was the biggest investment we’d ever made.”

His lot included 100 telegraph keys and sounders (to receive senders’ keystrokes), two Edison stock tickers, and 25 Western Union clocks. In their day, Western Union clocks were revolutionary. Made by the Self Winding Company from the late 19th to the mid 20th century, Western Union’s battery-activated, motor-driven, spring-powered pendulum clocks received time synchronized with the U.S. Naval Observatory over telegraph wires. They, in turn, transmitted the standard U.S. time to slave clocks throughout schools, businesses, and railroad stations.

The estate’s clocks had been stored in a chicken coop subject to all weather. “They were in terrible condition,” Edwards said.

Some he restored and gave to family members. Others he sold or set aside for their interchangeable parts. Or trashed.

He spent a month restoring one very blackened Western Union clock for his personal collection. “It’s a filthy, smelly job,” he said. “You get chemicals all over yourself. You mess up your garage floor and your wife’s kitchen counters. But you’re saving something from the scrap pile and bringing it back for future generations.”

Karen, who normally was quiet during our telephone interviews, joined in, “And you hope it will become a prosperous endeavor as well.”

Between that first estate purchase in ’88 and until his EDS retirement in 2000, Edwards said he was “working all the time” and “didn’t have any time for clock collecting.”

His next big estate buy – a horologic library – came from a living collector. In 2011, Edwards was asked to recommend a book appraiser for the estate of Chester Johnson, Santa Fe’s revered master clockmaker and the owner of the famed Antique Clock Repair shop. Johnson’s library contained rarities such as leather-bound 17th- and 18th-century works written on parchment, a late 16th-century book on sundials, another on astrolabes, and recent out-of-print books on barometers and theories on timekeeping and solar planets.

Despite ads in relevant horologic periodicals, the estate didn’t have any luck finding a buyer for the whole collection and called on Edwards, who, with Karen, visited Johnson, then 84, at his shop to negotiate. Though Santa Fe’s master clockmaker held back several works and periodicals, he sold the bulk of the 140-book library for what Johnson called the “great bargain price of $3,500.”

Edwards bought the library to sell at clocks shows, but he retained 10 works that catered to his interests in barometers, antique ship clocks, and sextants.

Two years later, the son of a deceased NAWCC member contacted Edwards about another private sale. When he went south to Galveston to view the collection, he was dumbstruck. “In my 25 years of collecting clocks, I’d never seen clocks like these on the local market,” Edwards said.

The 20 timepieces were early 19th-century Biedermeier-styled Vienna Regulator wall clocks. Their rectilinear architectural simplicity strongly appealed to his aesthetic. “It was a gut instinct,” he said. “I thought you could do well selling them, and the $8,000 price wasn’t outrageous.”

The prettiest of the three Vienna Regulators that he kept graces his office wall. Housed under a classic pediment, the clock’s eye-catching mahogany veneer panels bordered by lighter sandalwood encase three glass panes on the top tier, narrow-waisted middle, and bottom. Known as the “9 Light,” it has a German name, Laterndluhr, which roughly translates to “lantern clock.”

Its nearly 200-year-old movement — the oldest in Edwards’ collection — is original, but Edwards suspects the wooden casing and glass may have been rebuilt a century ago. “It doesn’t matter to me,” he said. “I still love it. It’s still a beautiful clock.”

In 2014, when Lone Star began organizing for the convention, Edwards volunteered for the steering committee. “I wanted to do my part to make the convention a success,” Edwards said.

Convention business took a minimum of two to three days a month for the next three years. “He is one of my two chairs, and if I die, he will take over my responsibilities,” general chair John Acker said.

First they had to secure a venue.

“The Fort Worth Convention Center was perfect,” Edwards said. “It had the right location, tourist attractions, hotels, easy access for deliveries. But Fort Worth refused to let us tie up a portion of their space two years in advance.”

So they looked at other accommodations. Happily, the Arlington Convention Center offered just the right size for the events and expected 1,100 attendees. More importantly, its $30,000 rental fee fit the host chapter’s budget.

At the same time, Edwards continued to expand his personal collection by going to regional and local chapter meets. He purchased his most beautiful chiming clock on a whim at a Lone Star auction. Near the end, a rare 6-foot, 5-inch electrically powered 1949 Revere grandfather clock came up for bid. It had five gorgeous large tubular bells suspended in a rich mahogany case. Edwards hadn’t even looked at it. But when the auctioneer announced it was electric, Edwards raised his hand. “I didn’t have to wind it,” he said. “And I liked the early-American tall clock look.”

Nobody matched his $75 opening bid. “Some clock collectors are snobs,” Edwards said. “They want nothing but mechanical clocks.”

At home, he discovered an unexpected benefit. The tubular bells played the traditional London Westminster sequence. “They resonate like church bells,” Edwards said. “I love their sound.”

A 2015 Nevada meet introduced him to a new genre, military clocks, and, in particular, the renowned Chelsea Clock Company of Boston. Chelsea had received its first U.S. government orders for marine clocks in the early 1900s.

Edwards had never paid Chelsea much attention until the Nevada dealer showed him a Korean War-era naval deck clock. The round, 8-and-a-half-inch 24-hour clock was housed in a no-nonsense black phenolic case with dust-proof, cork-sealed bezel with the manufacturer’s name and “U.S. Government” emblazoned in black on the white dial. “It was new to me,” Edwards said.

Its industrial look and reasonable $300 price tag appealed to him. It was a “keeper.”

The following year, Edwards joined other convention planners at meets at Louisville, Las Vegas, and other places to drum up excitement for the North Texas convention. He took his turn at the convention table answering questions, helping to fill out registration forms, and choose table locations. “Some wanted tables by the concession stand, by the loading dock, by the entrance door, or by their friends,” Acker said. “There was no logic for their choices.”

Edwards developed a $45 tour of the Cowboys’ and Rangers’ stadiums via an Arlington Convention & Visitors Bureau trolley for local and out-of-state visitors and came up with the entertainment for the banquet – a folksy cowboy poet in the vein of Will Rogers.

His most recent estate purchase occurred last year. A Fort Worth collector called the Lone Star club for anyone to buy a collection. “The gentleman was a motivated seller,” said Edwards, who accepted the invitation. “He was downsizing and wanted the clocks gone from his house.”

It was an extraordinary collection of early 19th-century wooden-movement mantle clocks. Some contained yellowed patent notices identifying them as made and sold by Seth Thomas and licensed by Eli Terry, the Connecticut clockmaker. Terry pioneered the mass production of affordable wooden clocks with interchangeable parts in 1816 in what some call the world’s first mass-produced machines.

Edwards purchased about a dozen, knowing they would sell well to collectors “because they were so early. They were a part of American history.” But he didn’t keep any wooden movement clocks for his personal collection. “They warp. They don’t keep accurate time.”

He has reserved four tables at the center of the NAWCC convention mart to sell a vanload or 75 clocks and watches worth up to $15,000.

*****

The 2017 convention mart – which will showcase heirloom clocks, vintage tools, sought-after parts, and horologic books – will occupy the entire 48,600-square-foot Exhibit Hall at the Arlington Convention Center. Demand for its 600 6-foot-long display tables from the 150 NAWCC chapters exploded just before the convention, forcing the organizers to open an overflow room for more tables. A group of mart tables will be dedicated to half-a-dozen silent auctions on Friday and Saturday.

The Ives clock exhibit in the Grand Hall, valued at nearly $500,000, is the largest-ever-assembled display of wooden-and-brass movement clocks made or licensed by radically innovative American clockmaker Joseph Ives from 1810 to 1850. Seventy-three spectacular Ives mantle, table, tall, and wall clocks, the last mounted on custom-designed panels, will be there. There could have been more, but General Chair Acker told exhibit organizer Philip Morris, “Stop. I don’t have anymore space.”

Retired lawyer George Goolsby, who’s loaning more than 20 Ives clocks, is driving up from Houston with his precious cargo wrapped in peanuts, bubble-wrap, and blankets snug in boxes cushioned by honeycomb mattress pads. “I don’t place them on the rear axle,” Goolsby said. “They ride like passengers.”

This exceptional show includes museum loans from the NAWCC’s National Watch & Clock Museum in Columbia, Pa., and the American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol, Conn. Some have never been seen outside their home location.

Ives is being honored with this historic exhibition because he revolutionized clock making in his own lifetime. As Philip Morris, author of the 2011 book, American Wooden Movement Tall Clocks: 1712-1835, said, “Ives is known for two significant inventions. His cantilevered spring that generated power as it unwound replaced the long weight-driven pendulum and permitted clocks to shrink to more compact, mobile cases. Secondly, Ives perfected the rolling pinions in the movement’s gears. The rolling pinions reduced friction and allowed Ives to produce 8-day clocks rather than the more common 30-hour.”

For the first time, the North Texas convention is offering the public a special deal. Visitors can attend the landmark Ives exhibition and expert lectures for free. Normally, admission to the mart and auctions costs $55 plus an $85 NAWCC membership. But the Lone Star Chapter will comp paying visitors with a free $35 four-month introductory NAWCC membership. It includes all the publications and, of course, entrée to the auctions and mart.

“Why should people pay extra for something they’ve never seen,” Acker said. “We just want to get them in the door.”

NAWCC National Convention, Mavericks of Time Thu-Sat at the Arlington Convention Center, 1200 Ballpark Way, Arlington. Free-$55. 214-467-0076.

I love this man dearly…Not many like him left in the world unfortunately

He’s a great guy and a positive influence on any organization!

Thoroughly enjoyed the article.

Don’t know what I would have done without him. I’d still be looking for tower clock help! Rick