Around 3 p.m. on a December Sunday in 2016, a 911 call sent D.C. Metro police racing to Comet Ping Pong, a pizza place in the nation’s capital. Employees and patrons with children had scrambled for safety after 28-year-old Edgar Maddison Welch stormed into the restaurant carrying an AR-15 rifle, which he fired at least once as he headed for a back room. That was where then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and her former campaign chief, John Podesta, were operating a child sex-trafficking ring.

Welch was so convinced that leading Democrats were sexually exploiting children that he drove four and a half hours from his home in North Carolina to rescue young victims, only to find that they didn’t exist.

The Associated Press reported that Federal Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson told Welch during his sentencing hearing in June that even though he had not physically harmed anyone, his bizarre actions had “literally left psychological wreckage.”

Ten days before Welch was sentenced to four years in prison –– a direct result of a widely disseminated lie and his own gullibility –– the University of Texas at Arlington announced a project to fight fake news. Much of the fake news that spread on social media in the months leading up to the election has been traced to Russian hackers.

Through grant funding and a partnership with professors at the University of Texas at Dallas, the UTA team will build computer tools to spot and flag social bots that create and spread misinformation. The team, headed by Chengkai Li, an associate professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, will use highly sophisticated algorithms to combat the bots.

The project, entitled “Bot vs. Bot: Automated Detection of Fake News Bots,” will focus on Twitter accounts run by computer programs that automatically publish and forward content, follow other accounts, leave comments, and conduct activity that seems “real” but isn’t driven by an actual person.

Li said the project’s focus is not on politics but rather on national security threats, since bots are often sponsored by nation states that are hostile to U.S. interests, such as Russia.

The associate professor said that a study of 140,000 Twitter accounts in the battleground state of Michigan found that in the 10 days before the election, about as many false, election-related stories were spread on social media as accurate ones. After analyzing political stories from the three months leading up to the election, Buzzfeed News concluded that fake clickbait headlines drew more readers than headlines based on factual news.

Such findings speak to the “significance of the problem,” Li said.

“Bot vs. Bot” is being funded through the Texas National Security Network Excellence Fund out of the University of Texas at Austin’s Clements Center for National Security and The Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law. The $30,000 seed grant was awarded last summer and will fund a year’s work. Li plans to seek federal funding to extend the project.

Besides Li, the project will involve: graduate students; Christoph Csallner, associate professor in UTA’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering; Mark Tremayne, an associate professor in UTA’s Department of Communication; and UTD professors Zhiqiang Lin, who is an associate professor of computer science, and Angela Lee, an assistant professor of emerging media and communication.

Tremayne said the group is looking to create a system of flagging posts, but a challenge to that effort is that oftentimes fake news contains a nugget of truth.

“You might find that a bot takes a piece of real and true information, then adds an element that isn’t true,” he said. “So, in the end, you have different levels of fake news.”

That’s not the only challenge.

“In many cases, even if you point out various evidence why something is fake, people may not buy it because of different ideology and so on,” Li said.

Li believes that any flagging will need to be supported by some sort of justification, such as determinations from experts that a particular site routinely spreads false information, or a certain Twitter account posts nothing but information from a routinely unreliable source. Also, he said, the system could inform social media users that a profile photo is an image downloaded from a site where photos have been downloaded for many fake accounts, or that a particular account tweets at a rate that indicates it is not human-driven.

“That’s an example of data mining,” he said. “You basically need to look at the track record of all of the accounts.”

This isn’t Li’s first venture into research that deals with fact checking. In collaboration with researchers from Duke and Stanford universities, he used grants from the National Science Foundation and the Knight Foundation to create ClaimBuster, an automated tool that has been used in checking the veracity of statements made by candidates in U.S. presidential debates. Tremayne, too, is a participant on the ClaimBuster project.

The “Bot vs. Bot” team began gearing up in the fall 2017 semester but is still in “the very early stages,” Tremayne said.

“Basically, the first step is really coming up with a system to identify automated social media accounts,” he said. “The idea behind machine learning is you give a computer program examples of fake news items, and you can program it to look at those items linguistically and look for certain elements, certain types of words, certain sentence structures, and it can actually begin to learn what a fake item looks like.”

Tremayne said that, with a flagging system, users would be able to see the warnings as they scroll through their feeds. People tend to share and comment on things that are “extreme and shocking,” he said, and most people might be surprised at how much information that is shared on social media is pushed out by bots, oftentimes for moneymaking purposes.

Russia’s interference, though, wasn’t about money.

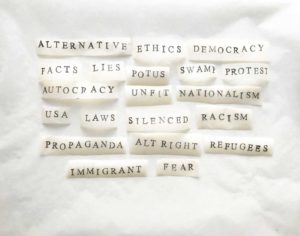

The purpose of the fake news bots during the presidential campaign “was to create confusion, to create division in the country,” Li said. They “certainly confused a lot of people.”

The purpose of the fake news bots during the presidential campaign “was to create confusion, to create division in the country,” Li said. They “certainly confused a lot of people.”

In December 2016, as the dust settled from a surprise win by Donald Trump that none of the top pollsters had predicted, several mainstream media outlets published articles about fake news and its prevalence during the election. The Los Angeles Times reported that only three of the top 20 fake news stories spread during the campaign cast a bad light on Trump. Fake news played such a significant role in the presidential election that Politifact named it its “Lie of the Year.”

A ranking by Business Insider of “the most ridiculous fake news stories” during the 2016 campaign based on Facebook engagements (shares, likes, and comments) included: a claim by famous drag queen RuPaul that Trump had touched him inappropriately during a party in 1995; WikiLeaks confirming that Hillary Clinton had sold weapons to ISIS; then-vice presidential candidate and Indiana Gov. Mike Pence calling Michelle Obama “the most vulgar First Lady we’ve ever had”; and then-President Barack Obama signing an executive order banning the Pledge of Allegiance in schools nationwide.

Snopes, one of the first online fact-checking websites, debunked the falsehoods, but who knows how many people who had read the original stories later learned that they were fake? The Obama/Pledge of Allegiance nonsense reached 2.2 million Facebook users, according to Business Insider.

“For those who care about accuracy and evidence, it’s time to recognize that something really has gone off course,” an article in Politico stated.

During the past year, much has come to light regarding Russia’s role in the spread of misinformation during the campaign. It was revealed during congressional hearings last October involving executives with Facebook, Google, and Twitter that more than 126 million Facebook users may have been exposed to inflammatory political ads from the Internet Research Agency, a company linked to the Kremlin.

Though the term has been widely used for more than a year now, fake news itself is not new.

Politico detailed how the spread of false information caused a series of horrific events after a toddler named Simonino went missing in Trent, Italy, in the spring of 1475. On Easter Sunday, a Franciscan cleric preached that the boy had been murdered by Jews and that they drained his blood and drank it to celebrate Passover. Though the story was without merit, it quickly spread. Soon there was another baseless claim: the child’s body had been found in the basement of a Jewish house.

Prince-Bishop of Trent Johannes IV Hinderbach ordered that the entire Jewish community be arrested and tortured. Fifteen people were burned at the stake, inspiring other communities to commit similar atrocities.

The papacy tried to intervene, but the attempts only caused Hinderbach to double down, spreading more false information. It is believed, Politico reported, that the roots of anti-Semitism go back to that chapter in history, even though it was never proven that Jewish people had anything to do with the little boy’s disappearance.

Not all fake news incidents from past centuries were as chilling as what happened in Trent.

In 1835, the New York Sun published a six-part series about the discovery of life on the moon. There wasn’t a word of truth to it, but in those days, that wasn’t particularly unusual. Many newspapers published short stories, poetry, and such.

Tremayne said that during the late 1800s, “yellow journalism” was common, whether news stories were outright false or were exaggerated or sensationalized.

“Eventually, readers got sick of it and moved toward a different type of journalism in the 1900s,” he said.

The Los Angeles Times’ December 2016 piece about fake new stated that by the late 1800s and early 1900s, “respectable papers refused to publish false stories.”

Still, that didn’t completely stop fake news. In 1938, the Federal Communications Commission investigated claims of mass hysteria following the radio broadcast of “The War of the Worlds.” The episode, presented by actor Orson Welles as a series of simulated news bulletins based on the 1898 H.G. Wells’ novel, allegedly caused mass panic –– but even those reports turned out to be fake news. The most extreme reaction to the broadcast was by a group of residents in Grover Mills, New Jersey, who attacked a water tower believing it was an alien.

Amusing though that incident may be, the water tower and “pizzagate” absurdities are indicators of how gullible the public can be.

Though Americans have always had political differences, modern day politically oriented fake news has deepened divisions and fueled hatred. Tremayne believes the rift began in1996, when Fox News debuted. The cable news channel was an instant hit, he said, drawing many conservative viewers away from CNN, which had been in operation for 16 years and had covered news down the middle.

“Also in 1996, you had every news organization going online and readers beginning to experiment with reading news online,” Tremayne said.

By the late 1990s, political blogs began to pop up, and people who might not have been avid readers of political magazines began reading those blogs, he said. They were also watching cable news channels that were growing increasingly partisan.

“And what you saw with blogs and what you saw with cable news and Fox was that if you were strongly partisan, your ratings tended to do quite well,” Tremayne said. “And when it came to political blogs, if you tried to be sort of moderate or neutral, you did not attract a lot of readers. But if you took a strong partisan stance one way or another, your blog tended to do better.”

During the George W. Bush administration, Tremayne said, MSNBC, which had started the same year as Fox and initially tried to report neutrally, started to move to the left. The cable channel “became sort of a liberal version of Fox News in prime time” and its ratings spiked, Tremayne said.

“There was a cultural shift,” he said. “People wanted some partisan news. They wanted some partisan media. And so that’s the environment that we’ve been in. My own feeling is that at some point it will probably follow the pattern of history, and it will shift back the other way where people will decide they’re sick of it, and perhaps we’re at that point. Maybe it’s reached the fever pitch of ridiculousness, and people will decide they’re fed up with it.”

Those on UTA’s “Bot vs. Bot” team aren’t the only soldiers fighting fake news. Shortly after the 2016 election, Melissa Zimdars, an assistant professor of communication at Merrimack College in Massachusetts, created a checklist of sites to serve as a guide for her students and others.

Not everyone appreciated her efforts. Zimdars said she received thousands of threats through voicemails and emails.

Zimdars said that headlines accompanying articles about her checklist focused on the fake news angle, even though the checklist also includes satirical news sites as well as partisan sites that are reliable and others that are semi-reliable.

“Some of the websites included on that list were not particularly happy to be associated with fake news, although I would argue that [some] probably still could be, because they circulate a lot of misinformation,” Zimdars said. “They encouraged their readers to let me know how they felt, and so I received thousands of hate messages, as did my employer, as did some of my students.”

Zimdars said that one of her students, who works in the campus library media center, received a phone call telling him that if he “knew what was good for him,” he would leave school rather than have her as an instructor.

The assistant professor said she created the checklist after noticing that her students were citing questionable information in their papers and that even some of her educated friends and colleagues were having trouble at times distinguishing fake news from factual reporting. Zimdars said she herself even fell for a bogus news story. It was about football, though, not politics.

“It could happen to anyone,” she said.

During the months she worked on the checklist, Zimdars shared it with friends who are librarians and journalists. Some asked to share it with their friends, she said.

“I switched it to public, and it spiraled out of control,” she said. “When I realized that it was being shared so frequently, it made me realize how people really do want solutions.”

It also made her realize that some purveyors of fake or questionable news wanted to “silence” her.

“Clearly, they couldn’t defend themselves on the merits of their content and what they were doing,” Zimdars said. “The only way they could defend themselves was discrediting someone who was analyzing them.”

She took down the checklist for a time to reorganize it, making it a tool that can stand alone without instruction. When she reposted it, the threats started again.

Zimdars said that she was taken aback when the firestorm first hit.

“It was a little scary,” she said. “There was a long weekend when I didn’t leave my house. I just kind of hunkered down.”

UTA’s Li said that figuring out how to distinguish real news from fake on social media won’t be nearly as difficult as changing attitudes among a deeply divided public.

“It’s an engineering problem, and every engineering problem has a solution,” he said. “My personal view is this is more of a social and political problem than [a] technical [problem]. It’s bigger than the technical challenge.”

The persecution of Zimdars, and Trump repeatedly labeling reputable media outlets as “fake news,” are indicative of what some believe is an increasingly toxic atmosphere for journalists and a danger to the free press. Trump has continued his attacks on the media despite criticism. Last summer, The New York Times reported that the human rights chief for the United Nations said that Trump’s repeated claims that some media outlets are “fake news” could constitute incitement of violence and has potentially dangerous consequences outside the United States. In his unusual criticism of a head of state, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein said it was “quite amazing” that freedom of the press, which the United States had defended for years and is a cornerstone of the Constitution, “is now under attack from the president himself,” the Times reported.

When House Democrats initiated an impeachment bid against Trump last November –– it failed –– their five articles of impeachment included Trump’s undermining of the freedom of the press.

Journalism professors Daxton “Chip” Stewart of Texas Christian University and Tracy Everbach of the University of North Texas are worried. Stewart has gone so far as to advise his students to take a self-defense class and has given them tips for staying safe at political rallies and other events where there are large crowds. His recommendations have included traveling in pairs when possible, scoping out an exit route, and, to the extent they are able, keeping their hands free –– “things that I certainly didn’t have to learn in journalism school,” he said. “I don’t think we ever thought we would have to learn that.”

Katy Tur, who covered the Trump campaign for NBC News and MSNBC, recounted in her 2017 book Unbelievable: My Front-Row Seat to the Craziest Campaign in American History what it was like being singled out by Trump at a rally in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, on Dec. 7, 2015. After Trump implied that she had lied in her reporting, the crowd seemed to “roar as one,” Tur recounted, and was like “a giant, unchained animal.” After the rally, the Secret Service escorted her to her car.

On May 24, 2016, when the presidential campaign was in full swing, a journalist covering a Montana congressional race was assaulted on the job. Ben Jacobs, a reporter for The Guardian, was body-slammed and punched by Republican frontrunner Greg Gianforte after Jacobs asked him for his views on the GOP healthcare bill.

Gianforte, who won the election, was charged with assault. He received a 180-day deferred sentence and was ordered to perform 40 hours of community service and attend 20 hours of anger management training. He also was required to pay a $300 fine and an $85 court fee. Jacobs donated his glasses, which had been broken in the assault, to the Newseum, a Washington, D.C.-based museum dedicated to journalism.

“I think that journalists are in peril just in standard situations now more than I think we have ever seen before,” Stewart said. “We’re so thoroughly and consistently demonized by politicians, by right-wing media, by conspiratorial [groups] out there. So many people are blaming us for society’s ills, calling us enemies of the American people, that we’re targets for violence. It only takes one or two loons.”

Everbach said that she is “very concerned” about potential violence against journalists, most of whom she feels are trying to inform the public “in a fair and accurate way.”

“When the president of the United States starts attacking the news media for reporting the news and calling them fake news, that puts the fourth estate in danger,” she said. “Journalists are there for checks and balances. That’s why they’re called the fourth estate, the fourth branch of government. So when the president starts attacking them, that should be of concern to all of us. The First Amendment says we have a free press, and he’s accusing them of lying and making things up. So I do think it’s a threat, not only to journalism but also to the public. It has the potential to silence journalists from getting the news out there. And in a democracy, that’s a huge problem.”

“When the president of the United States starts attacking the news media for reporting the news and calling them fake news, that puts the fourth estate in danger,” she said. “Journalists are there for checks and balances. That’s why they’re called the fourth estate, the fourth branch of government. So when the president starts attacking them, that should be of concern to all of us. The First Amendment says we have a free press, and he’s accusing them of lying and making things up. So I do think it’s a threat, not only to journalism but also to the public. It has the potential to silence journalists from getting the news out there. And in a democracy, that’s a huge problem.”

Everbach said that some supporters of Trump showed up at rallies wearing t-shirts with messages about lynching journalists. She said that many of UNT’s journalism students now worry what the future holds for them and their chosen profession. The university’s population, she said, is diverse, and most of its students do not come from privileged backgrounds. Many will be the first in their families to earn a college degree.

“After the election, I would say that a lot of them were scared,” Everbach said. “A lot of them expressed to me that they’re afraid of what is going to happen now that Trump is president and should they become a journalist, because if they become a journalist, they become a target and what would they have to deal with on the job. So we do have open discussions about those issues in class.”

Some students have decided to go into public relations or marketing instead of news reporting, she said.

Stewart described a similar reaction among his students at TCU, though some were thrilled that Trump won the election.

“A lot of people were really dispirited,” he said of one of his classes that met the day after the election. “I think it was a gut punch to a lot of students because of the way he is to women and minorities and gays and journalists. You could see their souls were hurting that this had happened. But maybe a quarter to a third of the class was pretty excited. We’ve got private school kids who were pretty well off and were excited that things were changing. Some of the ones who were most cheerful about it didn’t show for class that day. They were celebrating in their own way.”

Most of the students in TCU’s newsroom had a difficult time with Trump’s election win, Stewart said, particularly females and minorities.

“It was as if they had been physically assaulted,” he said. “You could just tell that they were psychologically struggling, accepting that our country had turned to this.”

Tommy Thomason, former director of TCU’s Bob Schieffer College of Communication and founding director of the Texas Center for Community Journalism, agrees with Stewart that self-defense training for journalism’s up-and-coming generation isn’t a bad idea. In the past 20 or so years, he said, 115 journalists were killed internationally, and about 20 have been murdered in the United States since 1990.

But are reporters in more danger now than ever before, largely because of Trump?

In his opinion, no.

“I think we’re overreacting if we say, ‘My gosh. Journalists are in more danger than they have ever been,’ ” Thomason said during a discussion in a recent Public Affairs Reporting night class. “There are parts of the world where journalists really are in danger.”

Thomason acknowledged that deliberate attempts were made by the Republican nominee to “gin up” crowds against the media during the 2016 presidential campaign, “but at no point did they ever attack journalists.” Despite hostile messages on t-shirts, “there have been no attempts at lynching journalists,” he said. As for Tur being given an escort to her car after a rally, Thomason said there are “police officers all over the place” and “all kinds of security” at rallies that feature appearances by a presidential candidate.

“At no point have they ever had to take journalists out because people were throwing bottles at them and things like Philadelphia fans did at the Dallas Cowboys,” he said.

Thomason was referring to a December 2014 incident in which fans of the Philadelphia Eagles pelted the Cowboys team bus and a Dallas media bus with eggs and beer bottles.

Thomason also pointed out that Trump has historically low approval ratings, indicating that the majority of Americans do not support his bashing of the media.

When Trump announced via Twitter on Tuesday, Jan. 2, that he would announce within days “the most dishonest & corrupt media awards of the year,” late night comedians Stephen Colbert of CBS’ The Late Show and Trevor Noah of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show used it for comedic fodder.

“Nothing gives you more credibility than having Donald Trump call you a liar,” Colbert said.

The comedy show hosts purchased ads hyping themselves as worthy of the awards, which Colbert dubbed “The Fakies.” Colbert even bought a billboard in Times Square, which he referred to as “the failing New York Times Square,” a reference to Trump’s repeated references to “the failing New York Times,” drawing laughs from his audience.

Though Trump has provided no shortage of material for comedians, journalists who cover national politics have, for the past year, covered a White House that treats them with open disdain and leaves them scrambling to fact-check a president who is himself a purveyor of fake news. CNN reported on Saturday, Jan. 6, that the Twitterer-in-chief has disseminated untruthful or misleading information almost 2,000 times. The cable news channel –– which is much despised by Trump, who routinely refers to it as “fake news” –– used four large, clear containers full of colorful gumballs to provide a visual for its viewers.

This is the life of the mainstream media in the “alternative facts” era of Trump. (“Alternative facts” was a term famously coined by Kellyanne Conway, a counselor to the president, in an appearance on Meet the Press after then-Press Secretary Sean Spicer claimed that the crowd that had witnessed Trump’s swearing-in was the largest “to ever witness an inauguration, period” –– despite ample photographic evidence to the contrary. Spicer slammed the mainstream media apparatus for its alleged attempts to “minimize the enormous support that had gathered on the National Mall.” Conway labeled his facts as alternative.)

Graduating journalism students seem fated to enter a profession at a time in history when facts are considered by some to be a matter of opinion and some supporters of political candidates think nothing of wearing shirts with messages about lynching journalists.

UTA’s Tremayne, who teaches courses in public relations and broadcast journalism, said the fears that Stewart and Everbach have for their students don’t apply to most of his students. He said he does have some concern, though, for former students of the university who are now covering politics for bigger media markets.

The danger “is obviously real,” he said. “The question is, how likely is it to happen?”

Thus far, staying safe on the job is not a subject that Tremayne has brought up in his classroom.

“I have enough negative things to tell students,” he said, mainly “about how much money they’re not going to make.” l

Find a story in an ultra-liberal tabloid bemoaning attacks on the media, and you can bet it will target Republicans and conservatives. And you didn’t disappoint. So you’re troubled that attacks on the media undermine the First Amendment and thus threaten our democracy? Sorry, it seems to me that if we are to presume that our democracy will stand media criticism of the president, we should likewise presume that it will stand presidential criticism of the media. The media isn’t above criticism.

And what do you propose about unbalanced reporting? Suppose of 100 armed robberies in a given period, 10 were committed by people with Hispanic surnames. If the media were to selectively report only the 10, it will lead to a false impression that most robberies are by Hispanics, even if each story is itself 100% true. The media’s selective negative reporting on Donald Trump in particular, and Republicans and conservatives in general, has itself contributed to distrust of the media.

I’m not troubled by false reporting from Russians; it’s Americans that I’m worried about.

The Russian collusion is nothing more than something made up by those who will not accept the 2016 election results, and don’t realize that a majority of Americans in a majority of states want nothing more to do with the Clintons and their corrupt behavior. I know that, and most Americans know that. We see through the little schemes of liberals and don’t buy into them.

It’s ridiculous to say that the MSM is not almost 100% Liberal. I would not like it if it was the other way either.

Reporters are not innocent victims of presidential attacks against journalism. Reporters are responsible for the criticism of the media because they are too unprofessional and, dare I say, entitled, immature and self absorbed to set aside their own political preferences and bias against certain elected officials and candidates, to do their jobs correctly – which is to report the facts without bias. Good journalism in the U.S. mostly died when reporters at CNN and other media outlets were sobbing about the results of the 2016 election while they were ON THE AIR. How unprofessional and immature! And it’s this self centeredness and entitlement mentality to not accept the person who was fairly elected by a majority of Americans in a majority of states that has caused most of the division among Americans. I didn’t vote for Obama either time, but I didn’t go around whining about that and letting his being elected impact me professionally or personally. I have enough maturity to not do that. I, and many other Americans, are fed up with the whining and childish behavior of liberals, particularly those in the media who are not supposed to engage in any behavior that shows their political preference.

Is it a sign that liberals are losing when the Weekly’s commenters mostly take the other side? Hope so.