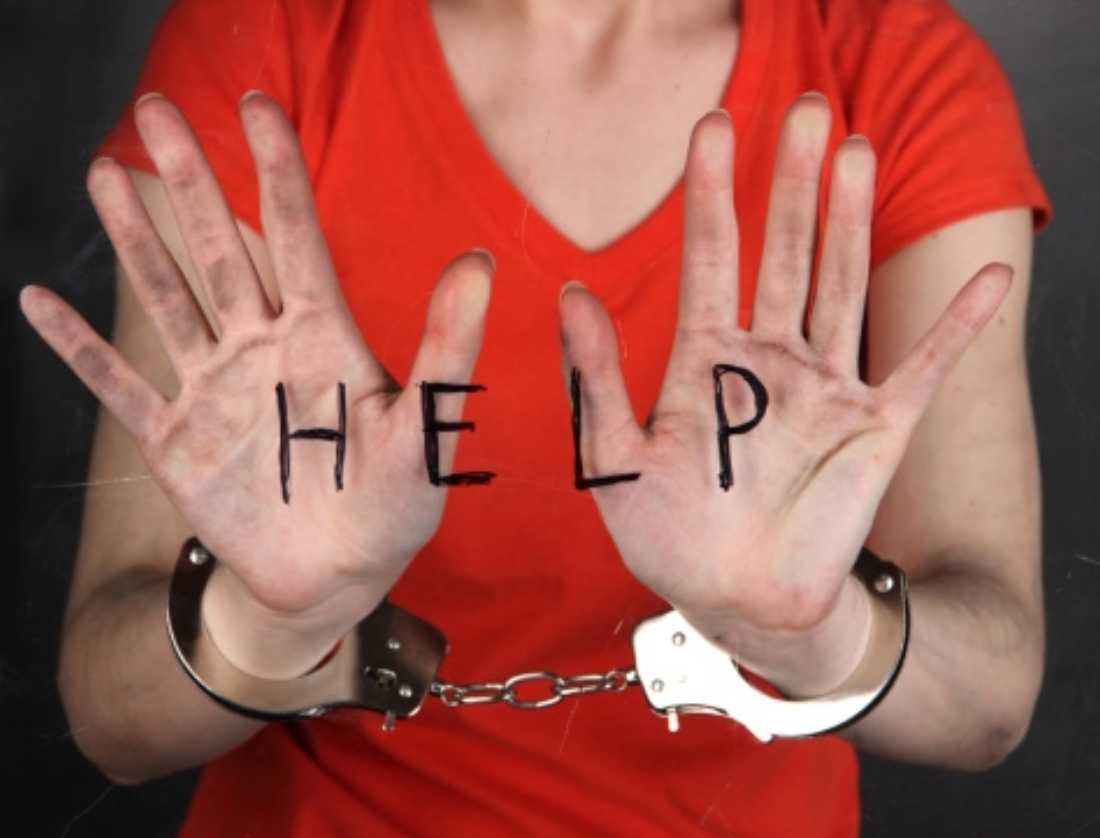

You’ve done the crime, been caught, found guilty, and sent to a state prison. Your primary connection to the outside world is via visits from family members. But suddenly you’re transferred from your own state’s prison to a facility hundreds or thousands of miles away. Phone calls replace in-person visits, but long-distance rates are expensive. Your connection to one of the most important elements of rehabilitation — your family — has just disappeared. You’re on your own now.

“If rehabilitation is the goal, sending people away from their friends, families, and communities is not the way to accomplish that,” said Holly Kirby, the author of a new report on moving prisoners from state to state. In fact, she said, it’s “one of the worst things you can do to a prisoner.”

In the report, prepared for an Austin-based nonprofit called Grassroots Leadership, Kirby concluded that interstate transfers of inmates, intended to relieve overcrowding in the originating states, ultimately does nothing to enhance the public good. The practice, she said, serves only the “interests of an industry that views prisoners as commodities and perpetuates our nation’s mass incarceration crisis.”

Corrections Corporation of America, the largest private-prison firm in the country, is the only company currently accepting cross-state prisoners, under contracts worth up to $320 million per year, the report says. Company officials did not reply to requests for interviews for this story.

Kirby compiled figures showing that more than 10,500 state-level inmates are currently serving their time in private prisons in other states. (Federal prisoners are not included in the report.) The farthest move: prisoners from Hawaii who are incarcerated in Arizona. Inmates describe being awakened in the middle of the night and loaded onto buses for a transfer, with no chance to notify their families. Some are moved multiple times, making it almost impossible for spouses, for instance, to relocate nearby.

Currently, only Hawaii, California, Idaho, and Vermont ship prisoners out of state, with West Virginia close to becoming the fifth. Receiving prisons are located in Arizona, Colorado, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Oklahoma.

“There is a dismal record of human- rights violations, lawsuits, and scandals that have followed interstate transfer of prisoners at the state level,” said Bob Libal, executive director of Grassroots Leadership, the 33-year old social justice organization that works to end the for-profit private-prison industry. “And those problems have led to some important changes in the practice, yet those four states continue the practice.”

Though Texas no longer either sends or receives interstate prisoners, key parts of that record of human-rights violations were written here. CCA was awarded the first contract from the federal Immigration and Naturalization Services for a private detention center and now operates nine detention facilities in Texas. The GEO Group, formerly Wackenhut Corrections Corporation, operates 12 prisons and several drug treatment centers in Texas, making it the largest private-prison company in the state.

Both companies have many black marks on their records for failing to protect inmate safety. Earlier this year, CCA lost two Texas contracts when the Mineral Wells Pre-Parole Transfer facility and Dawson State Jail were shut down. Dawson was shuttered after inmate deaths and reports of poor conditions.

The GEO Group experience in Texas is similar. In 1999 a dozen employees at a Wackenhut-run jail in Austin were indicted for sexual assault and related charges. Girls at the company’s juvenile justice center in Coke County were sexually abused by a guard; eight years later, conditions at the same facility were so bad that the Texas Youth Commission pulled all of the nearly 200 juveniles from the facility. In 2001 an inmate was beaten to death in front of the warden at the company’s jail in Raymondville.

GEO Group didn’t do any better when dealing with prisoners transferred from Idaho to Texas. In 2006 Idaho prisoners in the Newton County Correctional Facility were removed after they complained about abuse they received from prison guards. In 2007 an Idaho prisoner serving time at the company’s correctional center in the town of Spur in West Texas committed suicide; an investigation revealed squalid conditions.

John Miller, with the Associated Press, wrote at the time that the death made it clear that Idaho’s mantra for dealing with inmates sent to other states was “out of sight, out of mind.” In the story, Idaho’s prison health director described the Spur facility as “beyond repair” and said conditions included verbal and physical intimidation by the warden and guards.

Shortly after that investigation, 125 Idaho prisoners at the West Texas facility were moved to another GEO Group-operated prison in Val Verde, before Idaho finally severed its connection with GEO-run facilities in Texas. Idaho continues to ship some prisoners out of state, but not to Texas.

Kirby said overcrowding has been successfully addressed in some states through alternatives that allow nonviolent and first-time offenders to serve their time in rehabilitation rather than in prison.

One of the prisoners profiled in Kirby’s report is identified only as John — he didn’t want his real name used. He was convicted of sexual assault and lewd and lascivious conduct in Vermont in 2004 and given a six- to 20-year sentence.

“While in the prison in Vermont, I had between 15 and 20 people on my visiting list,” he told Fort Worth Weekly, “and never had a weekend pass without a visitor.” His son saw him frequently, and his parents came every weekend.

A few years into his sentence, he was awakened during the night, told to gather his things, and put on a bus with about 30 other prisoners, he said. A day and a half later, they arrived at a CCA prison in Kentucky.

“Initially my father and I described it as a ‘vacation in the South’,” he said. “But it was no vacation. I arrived in October 2006, saw my parents just after that and again just before Thanksgiving that year, and didn’t see them or anyone else — not a single visit — for 18 months.”

The isolation caused depression that led him to attempt suicide. It also exacerbated a heart condition that caused him to be hospitalized several times. “It was horrendous,” he recalled. “I was torn away from my support. I could call my parents every night, and did,” but the cost of collect calls nearly resulted in his parents losing their phone service.

Other prisoners from Vermont had a difficult time as well in Kentucky. “There was a lot of fighting among us that we didn’t have in Vermont. Some of the guys were deeply depressed. We had each other and no one else,” he said.

John was paroled in 2009 and has been an advocate for prisoners’ issues ever since. “I try to make people pay attention to the effects that out-of-state prisons have on inmates,” he said, “as well as trying to get those folks to focus on how to help people coming out of prison and back into our communities so that we’re not creating a cycle of recidivism.”

In the report, Kirby also focused on a wife who’d moved twice to be near her incarcerated husband and then discovered he was going to be moved again. The woman had no idea how she would be able to afford selling another house — and then not knowing how long her husband would be at his third prison before possibly being moved again.

“Imagine if you’re from Hawaii or Vermont and you get shipped to Arizona,” she said. “Shipping someone so far away isn’t just hard on the prisoner but very hard on their families as well.”

Libal said that sending prisoners so far away from families constitutes abuse. “The practice has got to stop,” he said.

The thing is ‘Pigs are going to be Pigs’….what else can they be??? God bless America. YEEeeeeeeeHawwwwww!