Night begins to fall outside a dilapidated 80-year-old former warehouse on Chester Street when a call echoes through the dimly lit, cavernous interior: “Turn out the lights! Let’s go!”

That’s Sabian Hernandez’s cue to heft his chainsaw, adjust his mask, and stretch to his full height of well over 8 feet. Striding into the gathering darkness, he swings the buzzing blade menacingly at people lined up along a wall.

It’s the start of another shift for Hernandez and 30 other scare actors at Junkyard Haunted House, located on a backstreet behind the Southside headquarters of the Humane Society of North Texas. As the night gets underway, Hernandez reveals himself as a man who loves his work.

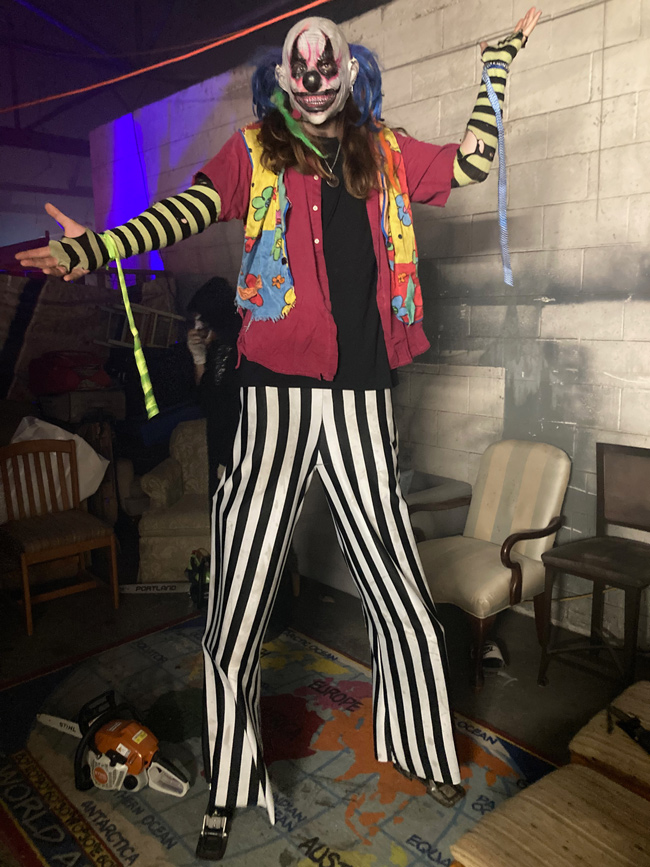

Perched atop 3-foot-tall stilts, clad in a tight striped costume, and wearing a black-and-white mask that Gene Simmons would approve of, Hernandez lunges energetically toward patrons waiting to enter the haunted house. Some cower before the roaring saw — actually a harmless prop — while others capture the scene on phones.

On any weekend night in October, hundreds of other scare actors across North Texas are similarly gesticulating, making faces, tottering like zombies, uttering ghastly screams and weird laughs, and otherwise plying their craft. Many work long hours, usually for no pay, often wearing hot and heavy costumes and not infrequently fending off rowdy and disrespectful customers. The actors say it’s all worth it.

“It’s a feeling you can’t explain,” Hernandez said of scare acting, also known as “haunt acting” or simply “haunting.” “Most people will never understand it — the fun of putting real fear into people.”

What does real fear look like?

Hernandez paused. “They pee,” he finally said, “or they take off running.”

For Hernandez, this sort of fun runs in the family — both his parents worked at Cutting Edge, the venerable Fort Worth fright attraction recently voted the nation’s top haunted house in a contest run by USA Today. With a decade at the gig, he’s practically an elder statesman on the local scare-actor scene.

Fellow Junkyard haunter Vanna Ryan plays a character clad in a torn white dress, adorned with dripping blood-red makeup, and named Mallory Chambers. Like most scare actors, Ryan created her own backstory to give her character depth.

“She was a girl who dared to break into an attraction at night,” Ryan said. “She didn’t make it out, and now she’s one of the monsters.”

Photo by Mark Henricks

As Mallory, Ryan lurks atop an old refrigerator and lunges down to claw at the faces of patrons squeezing through a narrow passageway. Shifts can be long.

“There have been nights when I’ve acted until 3 a.m.,” she said, and she drives nearly two hours each way to work from her home in Sanger.

None of this is too much sacrifice for Ryan, who dabbled with traditional acting before trying haunting. “I fell in love and decided this was the kind of acting I want to do.”

Part of the fun is the freedom. Scare actors typically have no script to work with, so improvisation is the rule.

Scare acting can produce income as well as fulfillment — Junkyard Haunted House pays actors $100 a night — but most performers labor for love alone. In fact, Ryan says this is her first paid scaring job, after nine years of volunteering at other scare attractions.

Junkyard owner Ricardo Hernandez (no relation to Sabian) said he was surprised to learn that most venues, including some of the area’s best-known, expect actors to work for free.

“We’ve always paid our employees,” said Hernandez, who also operates a Junkyard Haunted House in Dallas.

In Fort Worth, scores of people queued up to pay $25 a head within minutes of opening time on this mid-October evening. The fee is slightly less than at other venues, but seemingly even a lower-priced haunted house can produce ample black ink.

“It’s a good business,” Hernandez said. “It’s a very good business.”

Behind the profit, it’s not all gore and games. Ryan says that in addition to long hours of usually volunteer labor, haunters must cope with significant on-the-job hazards. These can include respiratory ailments caused by inadequately disinfected fog machines, lack of water breaks to hydrate, and frequent physical abuse from unruly patrons.

“I’ve been grabbed and hit,” Ryan said.

Sometimes, she said, this happens when surprised customers reflexively throw up a protective hand and accidentally contact a performer who pops up without warning.

At times, the physicality goes further and descends into intentional and even sustained violence.

“The girls, unfortunately, get groped,” Sabian said.

Not surprisingly, actors hope for more from their workplaces. Ryan has recently formed a group to advocate for better working conditions in scare attractions.

Risk to actors varies by venue. A performer at Six Flags Fright Fest says the theme park has security personnel who will respond quickly to an actor’s call for help. However, sometimes the damage is already done.

“We had someone who got knocked out cold when somebody punched her,” said the actor, who is not being named because she didn’t have the venue’s permission to speak.

Whether they work at one of the more desirable venues, such as Junkyard and Six Flags, that pay actors and provide breaks and responsive security or a volunteer gig where performers get fewer of both niceties and necessities, scare actors need to be physically robust. Six Flags’ job description includes constant standing, talking, climbing, reaching, stooping, crouching, bending, kneeling, and other activities.

More unusual talents may also be called for. Sliders, for example, are specialist actors who wear knee pads and armored gloves and slide across floors to frighten guests. Being a little wild probably won’t hurt. The popular Bedford haunted house Moxley Manor advertised job openings with the tag: “We’re looking for actors and makeup artists to help us scare the cr*p out of our victims.”

All this must be done wearing costumes weighing up to 20 pounds, often including masks, wigs, gloves, thick makeup, and little ventilation.

“My costume is really heavy and stiff,” the Six Flags actor said. “At the end of the night, all of us can hardly walk to our cars.”

If this sounds appealing, getting a gig as a scare actor is likely possible, even for beginners. Auditions, which usually happen in late summer, tend to be relaxed. Especially at voluntary venues, nearly anyone willing and able can get onboard.

Hours can reach 40 a week or more when houses start scaring seven days a week as Oct. 31 approaches. And some run from September through early December. A few open other times of year for Friday the 13th or Bloody Valentine shows.

However, generally speaking, this is part-time seasonal work that actors do either as a brief annual dramatic endeavor or as one of a variety of jobs throughout the year. That describes Sabian Hernandez.

“I’m the Easter Bunny, I do Uncle Sam, I do birthday parties,” he said. “Last year, I was part of the Dallas Christmas parade. I’m an entertainer.”

Then Sabian smiled, pulled on his mask, picked up his saw, and headed out to see if he could make somebody wet their pants.