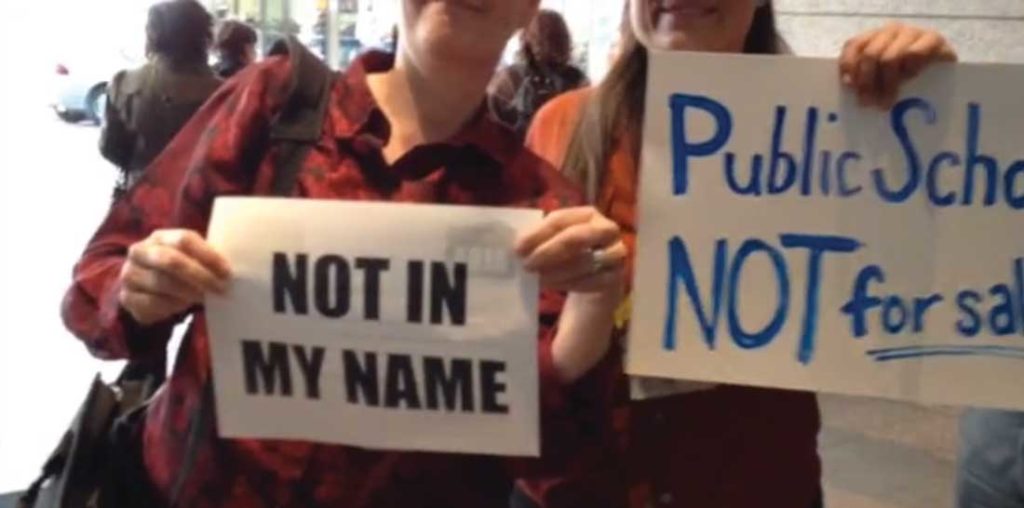

On a hot July day in 2014, protesters from the Badass Teachers Association swarmed the Department of Education in Washington, D.C., chanting witty jabs, wicking away sweat from their brows while hoisting high the signs they and their children had made the night before. Up and down the plaza they marched for hours, demanding that U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan come outside and listen, for once, to the problems of educational privatization.

Alongside the protestors, Mayme Francyne Huckaby marched. An associate professor of education at Texas Christian University, she asked questions about the students in question and asked how she could help.

Alongside the protestors, Mayme Francyne Huckaby marched. An associate professor of education at Texas Christian University, she asked questions about the students in question and asked how she could help.

Almost three years later, Huckaby is still asking questions and sharing answers, chiefly through her four-year ethnographic film and digital book project, Public Education Project: Participatory Democracy in Times of Privatization. Her films examine the impact of people’s resistance to educational policies established by laissez-faire economics and the privatization of schools across America. She’s spotlighted the stories of dozens of disenfranchised students, frustrated parents, and teachers severely lacking in financial resources and basic school supply needs. These stories don’t shine with the same veneer of ones you’ll hear on the 5 o’clock news. These stories are counterstories, ones that stare down waxy representations of public schools in mainstream media while using film to give voice and recognition to people the mainstream media forget to interview.

Films for the People

At a public lecture in February at TCU, Huckaby stood in front of dozens of Fort Worthians and wove together an intricate, tapestry-like narrative of her public education research, intentionally complicated by her philosophical stances as a black feminist, a budding documentarian, and an advocate of participatory democracy. On the floor of the sloping hall, she introduces the audience to footage of then 8-year-old activist rapper Asean Johnson protesting on that hot July day. Johnson personifies all the spirit of “Kid President” Robby Novak but with a willingness to tackle more serious issues. Audience affirmations soar in the background of the footage as Johnson reads his own educational bill of rights and challenges spectators to think about the government’s flippant attitude toward his underfunded elementary school.

Huckaby then showed footage of a concerned parent bringing compelling testimony before the school board of the Houston school district. The man stood at the front of the room with his tiny daughter, and he began listing off the first school where his children were zoned to, which the district promptly closed, followed by a second school that closed, and a third school up for closure — and that was then closed at the board meeting later that night. With persuasive certitude, he stated, “This is done on purpose to kill off communities. So are they going to have to relocate every other week when you see it fit, Mr. Grier?”

Then Houston Superintendent Terry Grier announced he’d be leaving office the following year.

In another short film, Huckaby unravels the anecdotes of community members who participated in the Dyett High School Hunger Strike of 2015. Dyett High was one of dozens of Chicago public schools that administrators had been threatening to close for years, citing poor test scores or dwindling graduation rates as the primary reasons for termination.

Jitu Brown sees things differently. As managing director of Journey for Justice Alliance, a grassroots organization that supports communities threatened by school closures, Brown was one of 12 hunger strikers who went over a month without eating. On camera, he speaks candidly to Huckaby about his participation in the strike, saying, “The Dyett Hunger Strike was the culmination of years of being ignored. We met with every bureaucrat. We jumped through every hoop. … In the absence of a vision for our children from the district, we created one. I think that people who are watching this should understand that in middle class white communities, they don’t have to develop proposals. They don’t have to do sit-ins and get arrested to get a return on their tax dollars.”

Brown’s expressions surge with energy as he turns slightly more toward Huckaby’s camera, explaining that he and other concerned community members realized that they would need to take more extreme measures when the Chicago school district “violated its own process,” cancelling a public hearing and giving no standard notice.

Looking back at Huckaby’s camera, Brown asks his imagined audience to “do the deeper analysis,” to realize that public education protestors don’t want to be entered into a charter school lottery and that they don’t want to be privy to special contracts or insider information.

“They just want the district to do its job,” he said. “And just for that, we had to go to that extreme.”

He pauses for a moment before confessing, “To me, [that] taught me what white supremacy looks like.”

On the 34th day, Brown and his fellow strikers brought their protest to an end. He said, “We didn’t stop the hunger strike because we were beaten. We stopped the hunger strike because we realized that [Chicago Mayor] Rahm Emmanuel would watch us die, and I mean that.”

Deep in Her Veins

For anyone wondering how a professor like Huckaby, who also holds the title of Director of TCU’s Center for Public Education, can step out of the ivory towers of academia and listen to the counterstories of educationally disadvantaged groups, ask her about her own experiences in public education.

“I grew up in the Third Ward of Houston,” she told me, adding that in the last few years three public elementary schools had closed in that neighborhood, leaving one elementary school left for an entire community to use. “What do they do?” she asks. “Things like that, I am really concerned about, and I know there is going to be a ripple effect into our future, that we are raising kids who are being disenfranchised from an education, and that has an impact on democracy. That has an impact on all of us. I see myself in others and others in myself.”

Huckaby hails from a long line of educators, and she’s got the family tree to prove it. A few years ago, she traced her lineage back to the mid-1800s — finding relatives in Texas and outside of Texas. The first ancestor who was free on her maternal side was her Grandma Humphrey.

“She was the daughter of a slave and someone who worked on the plantation, and her father, who was white, we thought was the owner,” she said. “But it turns out he wasn’t. It was probably his brother that was the plantation owner. He ended up having three daughters with a slave and sent them all to Oberlin College in Ohio. When they completed their education, [she] left Ohio and came south. Grandma Humphrey settled in Kendleton, Texas, and in some ways she planted a seed for the rest of us that came after her: Education was important.”

Huckaby reflected on how privileged her grandmother was. Born enslaved and the daughter of a white plantation worker, Grandma Humphrey was able to earn a college education in the late 1800s and as a black woman, no less. After her first husband died, she married a man named Benjamin F. Williams, who served three terms in the Texas Legislature while Jim Crow law was in effect.

In addition to serving in the House of Representatives, he was a delegate to the 1968-69 Constitutional Convention. He refused to sign the 1869 Texas Constitution because he was dissatisfied with the suffrage clause, according to Huckaby.

“One of the things he was really interested in was education and public education for all people,” Huckaby said. “From what I understand, Grandma Humphrey and Ben Williams were struggling on the [issue] of education, and establishing the right to vote for free people. So that’s been part of my family historically.”

Another maternal figure, the one after whom Huckaby was named, was a school teacher. This woman was Huckaby’s biological great-great-aunt, who in her mid-50s adopted Huckaby’s mother at 6 weeks old. Grandma Mamie Frances died in 1986 at the age of 97 but not without leaving an impressive educational legacy behind her. As the eldest child and first college graduate, she ensured that all but two of her seven younger siblings graduated with college degrees.

“One of the things she was most proud of was that, as a school teacher, she was able to ensure that all of her children got to go to college, which is pretty darn good,” said Huckaby with a laugh. “It was pretty darn good for the earlier half of last century to be able to send all of your black children to college. Not all of her children finished their college degrees, but the majority did. She was very determined to make it a path that was possible” for her students.

“In some ways,” Huckaby continued, “I don’t have a choice but to care about education. It’s in my genes. I can’t get away from it, and in some ways I know how hard my family struggled to ensure that the children of the family got a good education throughout the generations.”

After everything her family endured for the sake of education, Huckaby continues to fight for educational justice while wondering why this universal right presents such a hard struggle. She acknowledges the privileged position her education has afforded her while also commenting on how much harder it is for 21st-century parents to advocate for their children’s education.

“When I think about the decisions my mom made for me, the options that were available for her, and what she could do, it was easier for her in ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s to craft my early childhood care and then education. And it’s not that easy for parents today to do.”

With all the affordances and ease modern technology provides to our daily lives, she thinks it should be easier to craft a quality educational experience for any child, and yet, that’s still not the case. Now, too many people distinguish a “bad school” from a “good school” based on the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood around the school.

Second-Nature Segregation

As much as she’ll acknowledge the educational opportunity she’s been given, she asks, “What is [my education] worth if the generation that is existing now doesn’t have such a good opportunity?”

She continues to be surprised by the fact that some people couldn’t care less about any child’s basic rights to a strong educational foundation, but she recognizes that socioeconomic factors come into play once again.

“I know there are some benefits to the economic structure if we can work out where people belong earlier on in childhood,” she said, “so that in their adulthood they can get to a position where they can say, ‘I deserve to be doing this because of my background.’ But I don’t think we should work those things out on our children. I think adults should figure out that. … We are working out adult issues on kids. And that’s not right.”

Not all of the counterstories she hears make it onto her film roll. At a coffee shop near TCU last month, she told me about a conversation she once had with two teachers. One was a former teacher, the other a candidate for a school board position. After several hours blockwalking for election support, the teachers were conversing over pizza when one teacher explained that she didn’t have enough money to afford her students’ supplies. Her solution was to post a list of needed materials to the front of her school so parents could provide supplies, when possible. Another teacher who was nearby expressed similar concerns, but she knew the parents of her students wouldn’t be able to afford to send her extra supplies. The second teacher had to constantly ask herself, “Do I buy what my kids in my classroom need? Or do I buy what my kids at home need?”

Huckaby’s analysis of the dilemma pointed out the socioeconomic disparity between these two public school educators. “Here is a situation where one school district doesn’t have what [two] teachers need,” Huckaby said. “One teacher has extra resources to draw upon, and the other teacher doesn’t, just because of the way we are segregated in our society and the way in which our schools are built.”

Her experience and research show that this disparity is no accident. Rather, the way socioeconomic classes have diverged into different neighborhoods has been intentionally segregational with historical and sustained practices that include the structures of educational systems, housing, financing, and zoning, in many cases, and we’ve lost sight of the consequences of these society-driven divisions.”

As a black feminist, Huckaby draws upon the teachings of philosophical muses, especially Audre Lorde. At her lecture, Huckaby invited everyone to meditate on Lorde’s words: “The white fathers have told us, ‘I think, therefore I am.’ But the black mother within each of us, the poet within each of us, whispers in our dreams, ‘I feel, therefore I can be free.’ ”

In the case of the two teachers who couldn’t afford school supplies, she personified what she did not film, speaking as if she were one of the teachers, “ ‘Sometimes, I have to make a decision, a choice, and I’m cheating my biological children or the children I’m teaching.’ ”

That, she continued, “just changes everything about how you teach and the stresses you feel coming into your classroom. I don’t know that we think about these things carefully enough when [policymakers and their citizenry] think about policies.”

Huckaby’s alarming vignette resonates with a comment on her work made by another TCU education professor. “Her work creates a community in which people can be encouraged and inspired by the work of others that they would have otherwise never seen or heard but for the films created by Dr. Huckaby,” said Dr. Gabriel Huddleston. “Perhaps, this is her work’s true power: to connect us to each other so that we may continue to resist and fight for public education.”

Starting to Question

At the end of every lecture she gives, she leaves her audience feeling confounded, questioning, and yet, slightly hopeful. In February, one of the first questions she received hit on the appointment of Betsy DeVos.

“She’s not a surprise,” said Huckaby, peeling back the eyes of every audience member with some shock. “The last decade of educational policy we’ve seen has been leading up to this. She might be harsher and stronger than Arne Duncan, but we’ve been on a trajectory leading up to her for a while. What happened in Chicago will happen here.”

She went on to say that, given the increase in charter schools and voucher plans, public education in America could undergo some drastic changes in the coming years — to which she is no stranger. With the sincerest candor, she shared with her audience that “We could be witnessing the dismantling of public education in the U.S.”

Drawing on her experiences as a Peace Corps educator in the late 1990s, she also said, “In Papa New Guinea, we taught under trees. Maybe there’s a way to sustain what’s left of our current educational system, but if it falls apart, we start again.”

A professor in the audience asked Huckaby how she makes her entrée into other school boards and organizations in Texas, Illinois, and many other states. Entering a new educational community, Huckaby explained, is always tricky, but gaining the trust of parents and teachers in Chicago was one of her greatest feats as an activist. She started by offering to help their causes in any way possible, sometimes by handing out fliers or standing on protest lines. Eventually, the people she helped began to ask questions of her work. Before too long, she became the filmmaker protestors sought out.

Another audience member wondered about public education in Fort Worth, to which she responded, “Fort Worth does seem to have a lot of issues at play.”

But she said that she chooses not to be in the “capillaries” of the Fort Worth school district as much. Later, she’d share with me what she meant by this.

“In Fort Worth, I live here. I teach here. I go into schools here with my students. But I don’t know it in the capillaries in some of the ways I know other school districts. I’m reluctant to [speak on] it because I don’t know it as well.”

She also said that in Fort Worth, she represents TCU and works to forge strong relationships with local public schools, not to compromise the productive partnerships she’s started in Cowtown.

A closer look at her teaching and mentorship of graduate students in TCU’s College of Education shows that Huckaby doesn’t have to stand on the front lines in Fort Worth to have an impact. Jayna McQueen, a doctoral student and a former public school teacher whom Huckaby mentors, explained her admiration for Huckaby’s work and her willingness to invite students to join her film crew.

“The films [Huckaby] produces show the impact of school closings not only on the community as a whole but on personal lives,” McQueen said. “They are powerful. … From my work with Fran, I have created my own path to activism, which is what teaching is about: modeling, supporting, and then watching your students take off on their own journey.”

Cautionable on Fort Worth

What she could confidently say about local public school systems is that the increase in charter schools in Fort Worth and in Texas will likely continue to climb. The Dallas school district has been depleted more than Fort Worth’s, but the 36 and counting charter schools in Tarrant County continue to drain local resources.

Building new facilities is always a sign of progress. When Huckaby enters Fort Worth public schools to assess the undergraduate teachers she trains at TCU, she notices a lot of construction on Fort Worth campuses. She assumes the increased need for space is a sign of Fort Worth’s continued growth as a city, and she hopes this will reduce the need for temporary facilities on local school campuses.

“Texas has had a long, long tradition of having temporary buildings, where some kids get to go to school in the [permanent] building and some kids go to school in the temporary building,” she said.

From the beginning of grade school through the end of her high school, she never imagined that temporary buildings could be a sign of an inequity issue, not until she read Shame of a Nation, in which educator and activist Jonathan Kozol calls out the state of Texas for having so many temporary buildings on elementary, middle, and high school campuses.

“In the beginning, the temporary buildings might have been a quick solution,” she said. “But they age quicker, the bathrooms are typically in the permanent building, not the temporary building, and so some kids have to go farther to get to the bathrooms.”

To hark back to Lorde’s wisdom, Huckaby sees Kozol’s statement as one with which people must question which students are placed in the temporary buildings, how that placement makes students feel, and how sustainable this quick-fix solution is, particularly as public schools lose funding resources.

The arrival of spring brings frantic searching for affordably priced homes zoned to more reputable Fort Worth public schools, especially Tanglewood and Lily B. Clayton elementary schools. But Huckaby believes parents of school-aged children shouldn’t put so much weight on realtors’ claims about school districts, especially when those claims corroborate racial and socioeconomic segregation. Huckaby’s advice to concerned parents is to go into schools to see for themselves.

“You know a school is a good school if you go inside and then see what [the school] feels like,” said Huckaby, who believes that quality schools are staffed with teachers exhibiting caring feelings toward children. She encourages parents to pay attention to whether or not students in schools appear to be happy, to feel safe and comfortable, and are willing to do the work asked of them. Noticing the occasional rebellion or increase in noise level shouldn’t be cause for concern. When students demonstrate their ability to question rules, they demonstrate their engagement in the learning process.

“When we go into schools, and we see kids reciting the same thing in unison, that’s not a sign of learning,” she said. “That’s a sign of rehearsal.”

Likewise, when children make mistakes, an educator who responds gently with a clear lesson to be learned should be favored over educators who respond more punitively.

Of course, maintaining a thought-provoking, engaging learning environment tends to be easier in public schools zoned to wealthier white neighborhoods, where teachers have smaller class sizes and access to more resources. What’s problematic is when educators and policymakers assume more affluent students are more deserving of these learning environments.

“We go into communities that are poor communities, or immigrant communities, or communities of color, and we see what happens in those schools,” Huckaby said. “We want to blame what we’re seeing on the kids and the teachers, but we don’t want to step back and think: What are the structures at play? What are the finances that are working in these spaces? Even when teachers are well meaning, there might be biases at play. And those are things for us to think about.”

She invites her audiences to question the historical and contemporary education structures that made and maintain inequality, asking, “How [are we] complicit with [these structures]? We’ve blamed the children born into [these structures] too long and too harshly.”

And Huckaby hasn’t relented in her thinking about the state of public education in Texas and across America. She said that she was hoping to be in a post-production stage of documentary development by now, but the end of the story continues to unravel. “I don’t know what the end is,” she said. “But I feel like I need to be part of it.”

As she continues to film her documentaries and edit and write for her digital book project, her enthusiasm steams forward, never relenting in warmth or opportunities for critical expansion. When asked what drives her to keep going, she responded in a word: love. Like her philosophical muse Lorde once said, “In the recognition of the existence of love lies the answer to despair.”

In her parting words to me, she said, “The answer to despair is love. We act in a struggle and move into a struggle not because we want to fight, not because we want to struggle against something, but because we love what has potential.