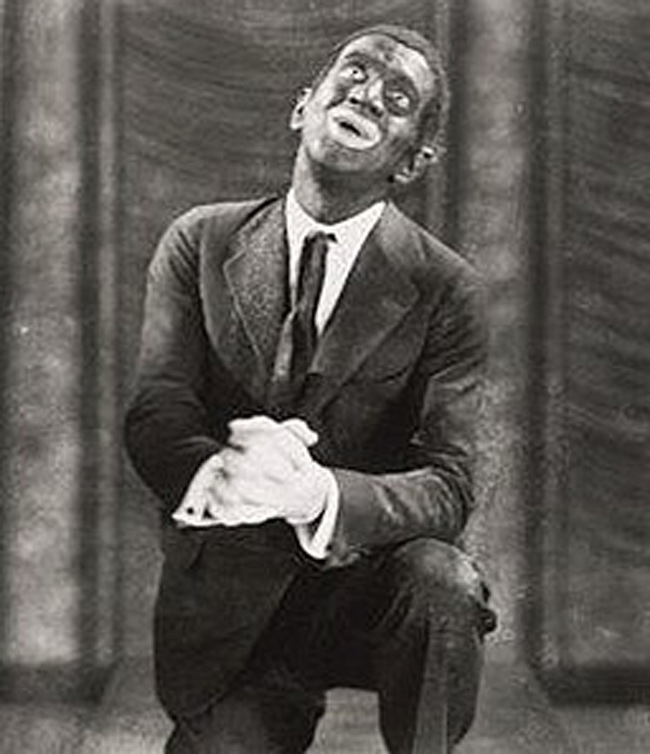

When Fort Worth’s oldest costumer opened in 1949, state law required separate Black and white seating on buses. Poll taxes and prison terms for interracial marriage were also on the books. This was 22 years after Al Jolson performed in Blackface in The Jazz Singer, eight years after the infamous crows scene marred Disney’s Dumbo, and a dozen years before Mickey Rooney donned yellowface as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Back then, the issue of cultural appropriation likely wasn’t on the radar at Harris Costumes, which then specialized in dressing C&W musicians, or anywhere else. Times have changed. Now, it pays to be careful what you sport for Halloween — or even what you suggest others wear. Just ask Megyn Kelly, who was bounced from NBC in 2019 after defending a white actor who darkened her skin before going as Diana Ross to a Halloween party.

If you walk into Harris’ store on Camp Bowie Boulevard today, you’ll find racks groaning under theatrical costumes depicting characters from the cultures of Native Americans, the Middle East, and many other places. You’ll find makeup that will let you tint your skin any color you like — and, if you appear ready to cross a cultural line, you’ll also get some gentle guidance.

“We’ve had people come in who are obvious about wanting to be someone of a different race,” says Lauren Rachall, a 15-year employee of the store who specializes in Beauty and the Beast costumes. “I try to steer them toward something different.”

For Halloween revelers aiming to avoid offense, it may not be enough to eschew skin-darkening. Cultural appropriation happens when members of one culture adopt elements of another culture, which tends to reinforce stereotypes and perpetuate prejudice. That may sound simple, but it’s hard to know exactly where harmless Halloween dress-up becomes harmful cultural appropriation, says Dr. Frederick Gooding Jr., professor of African American Studies at TCU.

“This is a murky topic,” says Gooding, who’s explored it in publications like his latest book, 2024’s Race and Media Literacy, Explained (or Why Does the Black Guy Die First?). “When you’re talking about race and culture and ethnicity, it’s so complicated. It’s hard to come up with hard and fast rules.”

Maybe you don’t need hard and fast rules to tell if a costume is out of bounds.

Courtesy Warner Bros. via Wikimedia Commons

“You know it when you see it,” says Cody McCoy, a partner at Panther City Syndicate, an event company that on Fri, Oct 24, will put on its second annual party and costume contest benefiting Southside Preservation Hall at the Southside venue.

The company’s past costume get-togethers haven’t featured any notable cultural transgressors, say McCoy and his partner, Leslie Downs, who says they’re comfortable with cross-cultural dress-up “as long as you respect the culture,” McCoy adds. “If someone shows up clearly being malicious, they’re not invited.”

Still, what’s clear to one person may be murky to another. So, Gooding has devised guidelines for cultural awareness in costumes.

First, Gooding says, ask if you have permission to dress cross-culturally. For instance, anyone can dress up as a police officer.

“There’s been no communication from police saying this is offensive to them,” Gooding says.

However, dressing up as a Native American is different.

“We’ve been put on notice,” Gooding says. “It’s been expressed that the feathers in the hat are not funny anymore.”

Next, Gooding suggests examining the costume’s purpose. If you’re invited to a ceremony specific to a certain culture, it may be appropriate to fit your dress to the culture as a sign of respect. If you’re dressing up for a Halloween party in hopes of snagging first prize in a costume contest, maybe not.

Finally, ask yourself: Who profits?

“It’s a different story if you’re wearing a costume that a close friend of yours from another culture gave you versus one you bought on Amazon,” Gooding says.

Power differential is another key feature. If you’re from a culture seen as dominant over another culture, costumes from the other culture are likely off limits for you. The reverse is also true. That means a Latina can probably go risk-free as Taylor Swift.

If this is too complicated, perhaps just don’t darken your skin. A non-Japanese might get away with a kimono and a chopstick-pierced wig. However, slather on yellow makeup, and you probably have crossed the line.

Still not confident about your costume? That uncertainty is telling you something. In short, when in doubt, pick another costume. There are ample options, and ghost, ghoul, and animal get-ups, to name a few, represent no risk of cultural appropriation.

The best way to handle a culturally inappropriate costume, whether on you or someone else, is to change to something else before leaving the house, Gooding says. With that in mind, a question put to a trusted friend or a private word from you to a friend whose costume may be risky are both good methods for avoiding a faux pas.

Costume parties are all about pushing limits, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. Company policies may prohibit “Not Suitable for Work” apparel at office Halloween celebrations, for example. Rachall says Harris Costumes often adds modesty panels to costumes too revealing for church and school productions.

Current political leaders’ embrace of anti-woke sentiment suggests that cultural appropriation is less concerning than when Megyn Kelly ran afoul of it. TCU, for instance, dropped its diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiative last spring.

“Five years ago, you could not throw together a DEI program fast enough,” Gooding says. “Now, times have changed. What we’re seeing is the swinging of the pendulum in the other direction.”

Pendulums aside, cultural appropriation remains real for event planners like Panther City Syndicate and costumers like Harris Costumes. We are not in 1949 anymore, and 2019’s Dumbo remake featured no crows. As Gooding says, “This is not your grandfather’s Halloween party.”