A silvery fish jumps in the air, curls toward the sun, and lands with a splashy smack before disappearing back into the water. Not an uncommon occurrence at a lake, until you consider that this happened last week near the south bank of Lake Worth.

For a hundred years, the city’s first public reservoir has been filling with silt, particularly along portions of the south bank where currents push the sand and soil. Water depth fell to a foot or two in many places, even near the lake’s center. Tepid and sullied water isn’t conducive to fish nor the people who try to catch them.

Two years ago, Fort Worth designated more than $100 million to be spent on dredging, clean-up, and infrastructure improvements including water and sewer lines in the coming years.

“You see people in boats and on paddleboards in parts of Lake Worth that have been inaccessible for 40 years,” said local historian Quentin McGown. “Nothing was going to happen out there before the dredging. It was going to continue to languish. Now, all of a sudden, there is a future.”

The dredging that has made the lake so clean and dandy for recreation has also made lakefront property more desirable for development than it has been in decades. At the same time, Lake Worth supporters are sticking with their calls for the city to save much of that property from intense development and, in the process, to create a green heart that would preserve a major swatch of nature and history as the city continues to expand.

Which of those futures should prevail?

Depends on whom you ask.

An Arlington-based development company has leased the old Casino Beach site and wants to create a boardwalk, amusement park, and music hall reminiscent of the spot’s 1920s heyday (“Casino Dreams,” May 7, 2014). Almost everyone is rooting for the project. But a plan like that is just a dream unless someone comes forward with about $30 million. So far, the developer hasn’t turned any dirt.

Casino Beach’s 20 or 30 acres are only a small part of the hundreds of open acres surrounding other parts of the lake. City planners, politicians, developers, financiers, and others tend to look at raw land and envision housing, businesses, and entertainment venues. Planners examine capitalistic what-ifs and foresee boosted tax bases. And they know where they can get their hands on a big chunk of prime lakefront property –– hello, Fort Worth!

The city owns a potential gold mine –– about 600 acres along the south shore, a massive sprawl of natural beauty with the lake stretching out on one side and the enchanting Castle on Heron Bay beckoning from a nearby hill. Several hundred more acres of city property are situated in a marshy basin near the lake, less desirable for development.

Everyone agrees that the land represents a financial windfall, but in different ways. McGown and others who fought for years to convince the city to pay for dredging insist that the best way to maximize the land’s potential is to do almost nothing.

Preserving that natural paradise as a public park could make Lake Worth the jewel of the city, they say. Few municipalities these days could afford to buy 1,000 acres of lakefront property, but Fort Worth’s already won that battle. Lake residents say establishing a massive park and protecting the area’s trees, wildlife, and serenity could be more profitable in the long run and push development onto private property also fronting the lake.

Lake Worth encompasses nine square miles and is situated less than 10 miles from downtown, on the West Fork of the Trinity River. Unlike Dallas, which is landlocked, Fort Worth could double its geographical size in the coming years. Fort Worth’s ability to annex land means that growth is steadily moving to the north and west, where other incorporated cities do not block the path. Supporters, like long-term lake advocate Joe Waller, predict that one day Lake Worth will seems like the city center.

Proponents say keeping the property in a natural state while also creating spaces for hikers, bikers, dog walkers, and families will transform Lake Worth into the equivalent of New York’s Central Park, something so rare and special it would attract people from across the city and beyond.

Convincing city officials won’t be easy. Over the years they’ve appeared to lean more toward selling off as much as 40 percent of the land rather than establishing a mega-park.

“It’s a serious battle, much more serious than getting this lake dredged,” Waller said. “That had to do with water quality, and everybody drinks water. As far as having a great parkland –– everybody in town doesn’t go to the park every day or need it for existence.”

********

A white pickup bounced over hills on dirt roads as it made its way across Silver Creek Materials, a quarry that sits about a mile from Lake Worth. The mining company sells sand, dirt, compost, and other organic products and for decades has been digging huge holes into the earth.

Talk about synchronicity. The cost to remove silt from lakes is astronomical, but city officials got lucky. Those huge holes at the quarry were perfect for holding mud and silt after it was sucked from the lake and transported by pipeline. Silver Creek Materials built five stairstepped dams and holding areas. Over a two-year period, the dredgers filled up the first hole. The mud sank to the bottom, and the water spilled over the dam into the next hole, and so on.

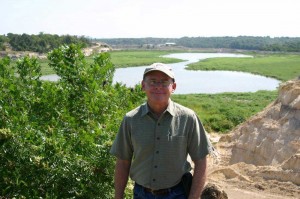

“This first area is where we built the dam a hundred feet tall,” said Bart McCay, the mining company’s chief operations officer, looking out over the five holding pits. “We held probably 90 percent of the solid materials in this one area — sand, topsoil, and silt.”

Now the water has mostly run off, soaked back into the earth or evaporated, and the first hole is almost filled with soil. The company got paid to accept the dredged material, and now they’re making money by selling it as compost and sand.

McCay said the city came out well too. Piping the dredged material for a mile rather than having to transport it by tanker trucks greatly reduced the city’s costs. Dredgers piped 2.2 million cubic yards of slurry from the lake to the quarry. How much dirt is that? Imagine stacking about 350 football fields on top of one another, each a yard deep.

City officials approved of extra dredging along heavily silted shorelines to create deep holes designed to trap silt, making it easier and cheaper to dredge in the future.

Most of the silt that overwhelmed Lake Worth was deposited in the lake’s first decade, when it was the only reservoir on the Trinity. After that, Eagle Mountain Lake, built just upstream in the 1930s, trapped much of the silt before it could reach Lake Worth, McGown said.

“We’ll never see the kind of massive inflow of silt we saw in those early years,” he said.

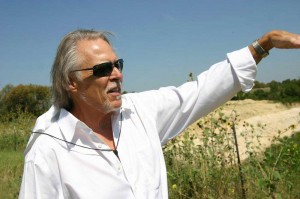

Waller visited the quarry many times during the dredging. He’s lived near the lake for 30 years and is one of its most enthusiastic proponents. The city-owned property is not far from his house. He’s been a strong voice on lake issues and served as president of the Lake Worth Alliance, a group of residents representing property owners.

Alliance members spent hundreds if not thousands of hours attending meetings, reading studies, compiling information, preparing reports, organizing residents, and meeting with city officials, all of which eventually led to the city’s decision to dredge the lake.

“This has been an intense effort over the past six or eight years,” he said. “For so many years this area was ignored. It was such a small lake and so shallow it didn’t seem very significant, so it was mistreated in a way, not given much attention as far as maintenance. After the demise of Casino Beach it just fell into disrepair.”

Casino Beach, established in 1914, was the area’s most popular draw from the 1920s through the 1940s. Stars of the big-band era played in the ballroom there. People danced, boated, strolled, and rode the Ferris wheel. But the 1950s introduced television and air conditioning to the masses, and the boardwalk scene began to dry up. Casino Beach and Lake Worth began their slow dance of deterioration.

“We just quit going outside,” McGown said. “The whole nature of recreation changed. By 1990 almost every vestige of the old entertainment complex had been demolished.”

Much of the money for the dredging came from Barnett Shale bonuses and gas royalties that flowed to the city before the price of natural gas tanked and drilling slowed.

“Our objective was to get the lake dredged, and the city voted in 2009 to allocate $117 million to do the dredging and some other infrastructure improvements. Huge!” Waller said.

Five years later, the dredging is done, the Lake Worth Alliance is disbanded, and Waller is feeling the wear and tear. But the fight has just begun.

Convincing city officials to keep their hands off the land could be even harder than getting them to fork over millions for dredging. Waller is unsure how much energy he can muster for the next battle but is considering re-forming the Alliance.

“I’m afraid that’s what it’s going to take,” he said. “There are too many powerful interests who want to reduce the amount of land the city owns. My vision is to use this for the public.”

He’s staggered by the thought of how much time and energy will be required for his group to convince city leaders to forgo short-term economic gain for a long-term vision. Waller and his colleagues will have to attend countless meetings, battle politics and bureaucracy, and pack the city council chambers with warm bodies when lake issues are discussed.

Waller, 69, is a natural leader, a retired sales director with an MBA in marketing, who can make strong points without coming across as arrogant or aggressive. Nobody has fought longer or harder to protect the lake. But that kind of passion takes a toll.

“I decided I was either going to have to quit or have less intensity, less passion, less involvement,” he said. “But without passion things don’t happen very well. People don’t listen. Passion transcends. With passion, they begin to embrace a vision.”

He serves on the Lake Worth Regional Coordination Committee, which the city pulled together a couple of years ago to study growth and development issues. In those meetings, it’s become clear to Waller that city leaders and many others who don’t live near the lake aren’t gung-ho about preserving the green space in its entirety.

As Waller says, “City planners like to plan.” And, so far, the planners seem to be winning.

“The people who want to reduce the size of the city’s ownership of land out here are in the majority at this point,” Waller said. “The will to preserve a big portion of it has gotten much more dicey in the past five years.”

Don’t dismiss a future Cowtown Central Park just yet. The cavalry might just ride over the hill with guns blazing at any moment.

********

Carter Burdette… He’s a piece of work. His support of fracking helped place a few thousand gas wells in the city and removed thousands of acres of green space for a known health and safety hazard; He got his stretch of Camp Bowie bricks whose year round maintenance costs taxpayers a bundle. Yet he still thinks we need more development in what little green space remains in FW. I say, screw him. Council needs to do the right thing and save what’s left for the wildlife and nature mystics.

Don, without Carter Burdette’s support and counsel regarding tactics for presentations to City Council and studies to support the requests for funding, I don’t think this lake would have been dredged today.

I definitely disagree with his beliefs regarding future use of city-owned undeveloped green space around Lake Worth. But he disagrees with mine….Still, all things considered, Councilman Carter Burdette was a strong and positive force for dredging and reclamation of Lake Worth.

I respect him for his work on that. But it’s in the past.

Now, we must go forward and encourage preservation efforts…and do that in a professional, balanced and effective way. At least that’s the way I see it. I agree that we have a fabulous opportunity here and should not squander it.