Adopting orphans from foreign countries comes with risk, but Kathie Seidel was willing to roll the dice. She was hurting. She wanted to be a mother again. For more than 20 years she had showered love on her only child, Brian, and his accidental death in 1989 had sent her reeling.

“Everything in my life was an adventure with Brian,” she said. “He was such a joy, and I wanted to have that again. Parenting was the best thing I ever did with my life.” Unable to bear more children, she decided to become an adoptive mother. At 40 and single, she wasn’t the preferred candidate for American adoption agencies, so she looked overseas. Her first adopted child came from Russia in 1993. Four-year-old Greg arrived with problems and charms. Hyperactive and diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, he was also intelligent, sweet, and loving. Seidel was crazy about him; he adapted well to his new home, and they quickly bonded.

“Everything in my life was an adventure with Brian,” she said. “He was such a joy, and I wanted to have that again. Parenting was the best thing I ever did with my life.” Unable to bear more children, she decided to become an adoptive mother. At 40 and single, she wasn’t the preferred candidate for American adoption agencies, so she looked overseas. Her first adopted child came from Russia in 1993. Four-year-old Greg arrived with problems and charms. Hyperactive and diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, he was also intelligent, sweet, and loving. Seidel was crazy about him; he adapted well to his new home, and they quickly bonded.

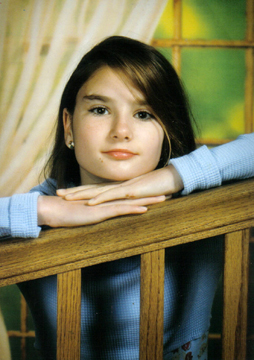

But this time around, she decided against raising an only child. Greg would get a sibling. The two adoptions together would cost $32,000, but Seidel’s career in computer software sales was thriving, and she could afford it. She chose a girl who had lived the first eight years of her life in a Russian orphanage. On the outside, Katia was slender, pretty, and dark-eyed. On the inside, she was a time bomb. “Katia came, and all hell broke loose,” Seidel said.

The girl bullied her new brother. She was autistic and slow to develop. Epileptic seizures appeared to have caused mild brain damage. And she was later diagnosed with attachment disorder, a behavioral problem associated with neglected or abused infants who miss out on being held, rocked, baby-talked, nourished, and otherwise loved in their first 18 months. These children have difficulty bonding with adoptive families and can exhibit destructive outbursts, known as rages, along with other socially awkward behaviors, including cruelty to siblings and pets, lying, and food hoarding, and often have difficulty establishing relationships with peers.

Seidel soon realized the girl was going to demand much of her time and resources, but she was up for the challenge. An award-winning volunteer at social service agencies, she’d earned a master’s degree in special education and had taught emotionally disturbed students for years. “Katia came to the right place when she came to me,” Seidel said. As it turns out, knowledge, experience, love, and determination don’t guarantee rosy outcomes. Seidel’s life turned upside-down. These days, she finds herself frazzled, heartsore, and broke. “My retirement money has been wiped out,” she said. While Katia’s condition certainly played a role in those problems, Seidel said her biggest obstacle has been overcoming what she and others call a fractured, underfunded, overwhelmed, and vindictive system that is supposed to provide services to people with cognitive disabilities in Texas. She’s spent thousands of dollars on attorneys trying to fight court and government actions that have replaced her as Katia’s legal guardian and moved the girl to a succession of institutions and group homes. “If you buck the system, they put your kid in an institution,” Seidel said.

Local officials hesitate to discuss Katia’s case, citing confidentiality issues, but they say Seidel wasn’t cooperative and that the girl is doing better after being removed from her home Tarrant County’s guardianship system, which deals with children, the elderly, and those not mentally capable of representing themselves, is considered among the state’s best. But the staff is overseeing 1,300 guardianship cases with limited resources, and some clients can be volatile. Robert Gieb, an attorney appointed to represent Katia, described Seidel as likely to torpedo most situations. “She’s convinced it’s her way or the highway, and she doesn’t like anybody who disagrees with her,” he said.

Seidel said she’s just fighting for her daughter against a stacked deck of judges, court investigators, attorneys, and agencies working to squash parents who demand services and attention. An expert in the field of attachment disorder is questioning how Katia’s case was handled. Other parents of mentally challenged kids describe a system that pits parents against officials in court battles in which everyone loses. “What happened to Kathie and her daughter is wrong, ” said Michelle Dooley, whose son was also ordered by a local judge to be institutionalized. After his release, she moved him to another city. “I will never have my son back in Tarrant County, because I don’t like the politics they play here.”

Seidel flew to Russia in 1993 to meet Greg before she adopted him. Her second adoption, in 1994, was different.

“With Katia, her orphanage director wanted to bring her here,” she said. “I found out later the main reason she wanted to come here was to buy leather coats and take them back to Russia and sell them.” Seidel was just happy to get a daughter and expand her little family. Before the adoption, she’d seen a photo of a thin girl in a simple dress with a huge bow in her hair. A video had depicted the girl walking and riding a stick horse. Everything seemed fine. When she arrived, the girl spoke no English but made it clear that her time in the orphanage was tough. She would pick up a tennis shoe and point to her bottom and imitate spankings. As she learned English, she gave more details.

“She had to clean the potties of the younger children and didn’t wear any gloves or anything,” Seidel said. “They worked in the gardens three times a day, and she didn’t go to school. They didn’t have much in the way of food. She told me about mice and bugs running all over the place.” Given up for adoption at birth, Katia arrived in the States with anger and self-esteem issues. She was born with only one ear and was embarrassed by the deformity. But there was a deeper problem. She could be sweet and joyful but also lapsed into rages. Sometimes she treated Greg like a trusted companion. Other times she’d physically attack him. “I’m going to kill you” was a common threat during the rages. Her behavior is typical for someone with attachment disorder.

“Katia knew that Greg had had a similar experience at the orphanage, but she thought he stood in the way of getting close to me,” Seidel said. “She was going to do anything she could to hurt him for many years. She didn’t understand when she got here that she and I would be just as close as Greg and I. It was hard for her to see there would be enough love for everybody.” Greg, now 20, is forgiving by nature, and he and Katia grew closer over the years. “She loves him now, and he is so good to her,” Seidel said. “She has worked so hard to get better.” Katia would be better off returning to her own home or at least being moved to a group home in Fort Worth that’s nearby, Greg said. Instead, she’s socked away in a Denton County group home and prevented from seeing her family regularly, even though she’s homesick, he said. “She’s supposed to have rights,” he said. “She’s 22, and she’s not even allowed to see her own family. For her to want to see her family so badly and not be able to is not right.”

Studies have shown that the best method for raising many developmentally challenged children is to integrate them socially and allow them to live and work around people without disabilities. Seidel tried to get home attendant care and respite services through Tarrant County Mental Health and Mental Retardation. But funds are so short that the waiting list stretches for years. Katia’s behavior, seizures, and need for medication meant Seidel was taking off from work often. Her income shrank. She wrote many dozens of letters to local and state agencies seeking in-home help. Finally, in 2006, she wrote to Gov. Rick Perry, explained her situation, and received permission from his office to be moved up on the waiting list.

Studies have shown that the best method for raising many developmentally challenged children is to integrate them socially and allow them to live and work around people without disabilities. Seidel tried to get home attendant care and respite services through Tarrant County Mental Health and Mental Retardation. But funds are so short that the waiting list stretches for years. Katia’s behavior, seizures, and need for medication meant Seidel was taking off from work often. Her income shrank. She wrote many dozens of letters to local and state agencies seeking in-home help. Finally, in 2006, she wrote to Gov. Rick Perry, explained her situation, and received permission from his office to be moved up on the waiting list.

The respite care never came. Within months, Katia was institutionalized despite Seidel’s pleading. Prior to 2006, Seidel had a good relationship with Tarrant County MHMR, where she volunteered. The agency awarded her a certificate of appreciation in 1999 for her “dedication, support, and valuable input.” Seidel said the relationship changed once she began pressing for home care and complaining to the governor about a lack of services. The last thing Seidel wanted was for Katia to be institutionalized; attendant care would have allowed the girl to stay at home with supervision, freeing up Seidel to work.

Seidel blames MHMR for providing what she said was false information to probate court officials that allowed them to remove Katia from her home and put her in Denton County’s Cimarron Living Center, a facility with a long track record of neglecting its residents. She also accuses local officials of removing her as Katia’s legal guardian in a closed-door meeting that she was not told about. She said court officials don’t understand attachment disorders and eventually prevented her from visiting her daughter. “This is what happens when there are no services available – families get destroyed,” Seidel said.

Katia’s behavior had been much improved in the months leading up to her institutionalization. In April 2006, she had started taking nutrition supplements under the care of a medical doctor. The effect was noticeable to Karyn Purvis, director of the Texas Christian University Institute of Child Development. She specializes in attachment disorders among adopted children from foreign countries and noticed that the supplements had changed some portions of Katia’s brain chemistry, which “meant fewer seizures, less behavioral problems,” she said. Whereas Katia used to rage once or twice a week, she had gone five months with only two rages, according to her mother.

But on Sept. 28, 2006, she had a setback. Katia came home from school – the Boulevard Heights Transition Center’s Life, Education, and Preparation (LEAP) program – in a bad mood after clashing with her special ed teacher. Too much stimulation and activity sometimes prompted rages, and Seidel spotted the signs. Katia squabbled with her brother and said she wanted to go to a Chinese restaurant. Seidel told her no, and Katia erupted, throwing a chair and kicking her mom. When Katia was little, Seidel could hold her daughter until the violence subsided. But Katia was grown and strong. Seidel called 911 for help, and an ambulance took the girl to a hospital. “I thought that was the safest thing,” Seidel said.

Instead, hospitalization set in motion a chain of events that led to Katia being removed from her home against her family’s wishes.

As she had done many times through the years during rages, Katia threatened violence. Threats are common with attachment disorder, often followed the next day by extreme sorrow and pleas for forgiveness. According to court records, Katia told hospital staff she didn’t want to go back home. Seidel, though, maintains Katia actually said, “I don’t want to go home until I’m better.” The next day, Tarrant County Probate Judge Pat Ferchill assigned a court investigator to evaluate the case. On Oct. 2, the investigator applied for the immediate removal of Seidel as Katia’s guardian, without bothering to notify the mother. Ferchill appointed attorney Robert Gieb as guardian ad litem to represent Katia. That same day, the judge assigned legal guardianship to a nonprofit organization, Guardianship Services Inc., which serves adults who lack the ability to manage personal or financial affairs.

On the order for removal, the judge noted that Seidel “did not appear at the hearing.” But Seidel wasn’t invited, consulted, or even aware of a hearing. The court can remove guardians without their knowledge in cases involving neglect or abuse, but people who know Seidel say she is her daughter’s biggest champion and defender and certainly no abuser.The judge wrote in his order that Seidel “has neglected the ward by refusing to have her assessed for more appropriate facility placement, leading to physical altercations between the guardian and the ward, ultimately leading to inpatient psychiatric care for the ward.”

Seidel, however, said she was a fall guy, that MHMR had failed to follow through with Katia’s assessment months before. Seidel didn’t complain at the time because Katia was doing so well on the supplements. Later, MHMR would blame her for not getting Katia assessed for respite care in a facility, and the court used that as a reason to remove custody of her child, Seidel said. She has spent every day since then fighting to get Katia back. MHMR did not respond to the Weekly’s request for an interview by press time. “What’s happened to Katia has been horribly grueling for her family, and her mom has been excluded from her care,” Purvis said.

Purvis wrote to Gieb on Oct. 7 describing how the supplement therapy had improved Katia’s behavior. She provided test results showing “significant shifts” in the neurochemicals associated with seizures and psychotic behavior and explained how crucial it is that adopted children with attachment disorder remain close to their families. “Our institute specializes in working with traumatized children adopted from international orphanages, and a cardinal principle in working with these children is to avoid isolation at all costs,” she wrote. The TCU institute recently received a $60,000 grant to provide training on attachment disorders and the effects of trauma, for judges, lawyers, caseworkers, and guardians ad litem across the state. “There is a great hunger to know more,” she said.

But Purvis never received a reply from Gieb. And Seidel said that Katia is no longer receiving the supplements.

“I offered to consult with them on Katia’s behalf,” Purvis said. “For a child that’s raised in an orphanage like Katia was, to be cut off suddenly from her family for a long period of time can be a very critical blow.” Purvis spoke with authority – she has known Seidel and Katia for 10 years. Katia was among the first children to attend one of Purvis’ TCU-hosted summer camps for kids with attachment disorder in 1999. Purvis has remained in sporadic contact with the family over the years. “Kathie is a fierce advocate for her children,” Purvis said. “She is an attentive mom and a devoted mom. Being a fighter for your kids can be misunderstood or misinterpreted. Quite frankly, a parent who is an advocate is a lot more trouble to work with for an agency or institution, and she is well studied on these topics.”

At first, Seidel was allowed to visit Katia. But after she began complaining about the low quality of care being provided at the group home, she said, she was barred from seeing her daughter and could only get limited and monitored time on the phone. The isolation was exactly what Purvis had explained to the court would be most traumatizing for Katia. “Why wouldn’t we partner with a parent who wanted to be involved?” Purvis said. “Why would we strip a child from her mother? I’d challenge anybody – if you took Katia away from Kathie Seidel and gave her to any other family, agency, or authority to raise and they spent about 30 days, they’d see that moms like Kathie who fight for their kids are extraordinary.” When considering cases involving guardianship, investigators in Ferchill’s court sometimes call on Paul Kaufman, a principal at a Fort Worth Independent School District school that offers transition programs for special ed students. Kaufman told a court investigator that Katia was from a loving family and that Seidel supported her daughter’s participation in a program designed to increase independence, find jobs, and use public transportation.

His comments don’t appear in public documents regarding Katia’s guardianship case. Kaufman met Seidel a few years ago at a social services meeting and saw the contentious,  persistent personality that rubs so many officials the wrong way. After the meeting, he initiated a conversation. “The perception that everybody had was based on the fact that if Kathie felt like she had to fight to get what was right, she wasn’t going to roll over and do what everyone wanted her to do,” he said. “Not everyone welcomes that attitude. I do.” Kaufman told her he was interested in helping her daughter, and he saw another personality emerge. “She became very reasonable,” he said. “I never saw her doing anything I felt was unreasonable. I haven’t had any issues dealing with her, and I explained all that to the person at the probate court when I was talking to the investigator there.”

persistent personality that rubs so many officials the wrong way. After the meeting, he initiated a conversation. “The perception that everybody had was based on the fact that if Kathie felt like she had to fight to get what was right, she wasn’t going to roll over and do what everyone wanted her to do,” he said. “Not everyone welcomes that attitude. I do.” Kaufman told her he was interested in helping her daughter, and he saw another personality emerge. “She became very reasonable,” he said. “I never saw her doing anything I felt was unreasonable. I haven’t had any issues dealing with her, and I explained all that to the person at the probate court when I was talking to the investigator there.”

Kaufman, however, is perplexed. He has dealt with Ferchill’s court investigators and Gieb many times before and describes them as devoted to the wards they are assigned to protect. “They do an outstanding job, in my opinion, for looking out for children,” he said. “I’ve got nothing negative to say about that court at all. They are on my side on the front line in taking care of folks, and something happened here that I don’t get … . The deal with Kathie is the first time I’ve not understood what happened.” So how do two entities he admires – a court system and a devoted mother – become enemies in a controversial battle to get care for a young woman? He figures there was a communication breakdown.

“Clearly Kathie is not evil and corrupt, and clearly the court is not evil and corrupt,” he said. “When she is fighting she does not appear to be reasonable, and it takes a lot to cut through that and see there is a reasonable person in there. It’s possible she was perceived by the court as being unreasonable and irrational, I don’t know.” To Seidel, what happened in Katia’s case seems simple: She pressured local agencies for services, became a squeaky wheel in a strapped system with little tolerance for such, got crossways with officials, and was smacked down and cut off from her daughter. She too worries about Katia’s privacy and at first didn’t want to go public with the story but did so as a last resort to try to regain guardianship of her child or at least get her returned to Fort Worth. Some parents who have mentally disabled children are happy to have their burden lightened by having their children institutionalized. Others keep their children at home and do the best they can. Parents who want their children at home but also want services face one obstacle after another, particularly in states such as Texas that traditionally rank near the bottom in funding for social service programs.

“Most parents don’t have the background I have and don’t know the child’s rights like I do,” Seidel said. “They don’t have $25,000 to go to court and fight it, or they’re too scared. Nobody ever fights it.” Tarrant County probate judges determine whether disabled persons should be assigned guardians. Ferchill, who removed Seidel as her daughter’s guardian without notice, did not respond to several requests for an interview. Court investigator Paula Conley, who recommended the guardian change, spoke to Fort Worth Weekly about guardianship cases in general but would not specifically comment on Katia’s case, citing confidentiality. “There is a priority for serving as guardian, and if the family members are appropriate and they are taking care of them and there is no allegation of abuse or neglect, we always look to the family first,” she said.

Ferchill’s office employs masters-level social workers to help oversee cases and requires guardians to file annual reports.

Donna Baugh is development director at Texas Guardianship Association, formed to promote communication and cooperation among individuals, organizations, agencies, and courts concerned with guardianship. She views Ferchill’s court as top-notch.

“Judge Ferchill is a big supporter of our organization and is probably one of the most active at monitoring his guardianship cases,” she said. “He wants to make sure the wards he is in charge of are being cared for properly. They have a group that goes out and investigates yearly and tries to figure out if everything is the way it is supposed to be.” One of those annual visits was done in April 2006 at Seidel’s home and found no problems; six months later, she was considered an unfit guardian. Baugh empathizes with parents who want to keep developmentally challenged kids at home. “It’s very difficult to get home-care services,” she said. “People are on the waiting list for years. Texas is near the bottom of the 50 states when it comes to social services.”

In lieu of home care assistance, many such kids are sent to institutions or group homes. Horror stories abound about many of these places, and Baugh said parents shouldn’t hesitate to complain if they witness abuse or neglect of patients. Seidel said complaining about Cimarron and the group homes where Katia has been staying has only resulted in her being labeled a malcontent and made it more difficult for her to get any contact with her child. Many of Ferchill’s cases involve wards with relatives under stress, and the court intervenes only when necessary, Conley said. “If there are problems – and with 1,300 cases there are going to be problems – if the guardian contacts us we’ll try to facilitate some sort of resolution,” she said. So, what happens when a resolution can’t be found and the court makes a decision that a relative doesn’t agree with? “They always have the option of hiring an attorney,” she said. Seidel, so far, has paid more than $20,000 in attorney fees fighting the probate court’s decisions. She said most of the money was spent setting up meetings with Guardianship Services and Gieb and negotiating visits with her daughter, but she’s been unsuccessful in changing the decision. Ferchill hasn’t shown interest in meeting with her, she said, and Gieb told her that the judge “listens to his own people.”

Asked whether the court sends wards to institutions such as Cimarron that have been accused of neglect and garnered low scores during state inspections, Conley said, “I’m not going to go into specifics. I know what this is about. I don’t want to talk about a specific facility. We look at all the facilities that we use. We are concerned about every facility, and we try to be aware of the staff and the problems, and any problems that come to light we will investigate and look at. “If we think the facility is not meeting their needs, we’ll move that ward,” she said. How quickly that occurs varies. Katia was eventually moved, but Cimarron and other poor-performing facilities remain open. Other wards get sent there. Conley couldn’t name any facility that had ever been removed from Tarrant County’s list of care providers as a result of poor care.

Asked whether the court sends wards to institutions such as Cimarron that have been accused of neglect and garnered low scores during state inspections, Conley said, “I’m not going to go into specifics. I know what this is about. I don’t want to talk about a specific facility. We look at all the facilities that we use. We are concerned about every facility, and we try to be aware of the staff and the problems, and any problems that come to light we will investigate and look at. “If we think the facility is not meeting their needs, we’ll move that ward,” she said. How quickly that occurs varies. Katia was eventually moved, but Cimarron and other poor-performing facilities remain open. Other wards get sent there. Conley couldn’t name any facility that had ever been removed from Tarrant County’s list of care providers as a result of poor care.

Gieb said Cimarron and other institutions aren’t perfect, but neither is life. The court determined Katia would be better off at Cimarron than under Seidel’s care. “It was the thing that had to be at the time,” he said. In June 2007, Seidel filed an application with the court to have Katia removed from Cimarron after reporting neglect and abuse of her daughter by staff and other residents. In response, Gieb wrote that the idea of removing Katia from Cimarron was “without merit and should be rejected.” The application was denied. Last week, the Weekly asked him why he would defend an institution that typically receives low scores for poor service to residents and laud that institution as a better environment for Katia than being with her own family, who wanted her home. “I’m not unaware of the fact that Cimarron has problems,” he said, but added that Katia “wasn’t there that long.”

Katia spent almost a year in the institution before being moved to a group home. “Bob Gieb doesn’t view my daughter as a person,” Seidel said. “Would he think a year is not very long if it were his daughter in there?” During a conversation between Gieb and the Weekly, he warned against printing a story favorable to Seidel. “You’re about to drive off a cliff on this,” he said. “I’m not saying government is perfect. Everything I can see that was done was the prudent thing to do – not perfect, but the prudent thing.” He described Katia as happy and content in her new group home. “She had a difficult case and had a difficult life, and Ms. Seidel doesn’t know how to deal with her daughter,” he said. But he wouldn’t go into details about why Seidel is considered an unfit guardian.

After a short conversation, he said he had to attend an appointment but agreed to meet with the Weekly for another interview. However, a few days later he sent a letter saying, “I do not see how any further conversation will be productive for you or me, or, more importantly, the ward. I suspect that you have determined your point of view for your article, and that you are now simply filling in the support for that viewpoint.” He continued, “While you find the ward’s mother, Ms. Seidel, to be credible, I do not. Obviously, neither did the court.” Gieb wrote that he does believe Seidel loves Katia. “However, the ward’s problems are severe and complex, and [it] proved to be beyond Ms. Seidel’s ability to deal with those problems.”

Critics of the mental health system in Texas say confidentiality issues provide the perfect hiding spot for officials seeking to avoid responsibility for their actions. Group home providers, for-profit institution owners, and various agency officials can dodge questions when a ward’s care is criticized. Allegations of abuse or neglect from people with mental impairments are often ignored. And even when problems are proved, tort reform laws have capped the amount of money an institution or provider must pay, which means many lawyers won’t or can’t afford to take the cases. After exhausting her resources on lawyers, Seidel recently persuaded Dallas attorney Kimberly Stovall to help her on a pro bono basis. A veteran of numerous cases involving MHMR, their wards, and care providers, Stovall helped secure an $11 million court decision against a group home in the Houston area after a resident died of neglect in 1998.

Abominable conditions at state institutions for the mentally impaired came to light in the 1970s and ’80s and led to a move toward smaller group homes, many of them nonprofit and community-based. But over the years, large for-profit corporations have swallowed up many of these smaller providers. News reports have documented continuing problems at many such facilities, where employee pay is often abysmal. Nowadays, Stovall said, few attorneys are interested in pursuing lawsuits. With tort reform, that $11 million settlement would now be about $250,000, hardly enough to cover legal fees in a lengthy court case, she said. But just because the case filings have diminished doesn’t mean the abuse has stopped at group homes and institutions. “There is more abuse now than ever before,” she said.

Cimarron is a 116-bed facility in Lewisville that operates largely on state and federal funds. Records from the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services records show that, twice in the past three years, Cimarron has been in danger of losing its certification because of deficient practices. Its overall rating of 40 out of 100 is well below the state average of 90. Allegations against the facility include poor medical care, theft from residents, resident-on-resident violence, insufficient staff to monitor the residents, failure to report allegations of client mistreatment, and at least one sexual relationship between a transvestite staff member and a male resident. The Weekly’s calls to Cimarron seeking comment were not returned.

Guardianship Services Inc., the organization that supplanted Seidel as Katia’s legal guardian, refused to discuss particulars in the case. “We are very protective of our clients’ confidentiality, so I am not going to be able to say a lot about Katia herself,” said Colleen Colton, the company’s executive director. I asked to speak to Katia in person. “We would prefer that you didn’t.” I asked why not, since Katia is an adult and, while having some mental, emotional, and physical difficulties, is relatively high-functioning (she has an IQ of about 80). “I’m not going to get into an argument about whether you can talk to her or not,” Colton said. “I would prefer that you didn’t, and I know the court is concerned about that too. She has a right to privacy and a right not to have everything spread out over the newspaper.” Doesn’t she also have the right to say whether she wants to talk to a reporter? “No, because she is under guardianship,” Colton said. When asked about the court’s decision to send Katia to Cimarron and the problems documented there, she said, “I don’t think I want to comment on the quality of a provider. I could get in trouble there. Every provider has its ups and downs.”

Michelle Dooley’s son, Morgan, has cognitive disabilities, and the Fort Worth woman has had her own battles with local agencies in trying to get services. She met Seidel years ago, and the two have compared notes. Morgan received therapy and other services paid through MHMR, but once he got older, stronger, and more likely to rage – and the available funding diminished – that began to change. The agency proposed that the boy be institutionalized, something Dooley resisted. “I would rather have him at home than in an institution any day of the week,” she said. “State schools and state hospitals are not run very well. There is a lot of abuse that goes on. I’ve seen it first-hand.” In 2002, when Morgan turned 16, the court ordered that he be placed in an institution in Wichita Falls after Dooley called police during one of his rages. Police showed up with guns drawn, and she begged them to be gentle in dealing with him. After he was institutionalized, she began noticing bruises and, at one point, he sported a black eye. She said staff was treating him roughly. He was later moved to a group home in Denton and is doing well, she said.

Michelle Dooley’s son, Morgan, has cognitive disabilities, and the Fort Worth woman has had her own battles with local agencies in trying to get services. She met Seidel years ago, and the two have compared notes. Morgan received therapy and other services paid through MHMR, but once he got older, stronger, and more likely to rage – and the available funding diminished – that began to change. The agency proposed that the boy be institutionalized, something Dooley resisted. “I would rather have him at home than in an institution any day of the week,” she said. “State schools and state hospitals are not run very well. There is a lot of abuse that goes on. I’ve seen it first-hand.” In 2002, when Morgan turned 16, the court ordered that he be placed in an institution in Wichita Falls after Dooley called police during one of his rages. Police showed up with guns drawn, and she begged them to be gentle in dealing with him. After he was institutionalized, she began noticing bruises and, at one point, he sported a black eye. She said staff was treating him roughly. He was later moved to a group home in Denton and is doing well, she said.

Dooley, Seidel, and other parents interviewed for this article shared similar problems in raising handicapped children and in getting services while at the same time trying to keep their children at home. They said the Tarrant County probate court system doesn’t always have the clients’ interests at heart and can be retaliatory. “There are a lot of parents like me who want our kids in the community and want them to be contributors to society,” she said.

[…] of this blog in June 2014); Fort Worth Weekly, Saving Katia, Jeff Prince, Posted July 2, 2008 ; https://www.fwweekly.com/2008/07/02/saving-katia/; Real Mommies and Daddies of the Real America…and Their Children Who Want to Come Home […]