These days, everyone knows — or thinks they know — the script for returning veterans. They come back from deployment and try to fit back into civilian life approximately where they left off. But the homefront can turn out to be a battlefield of its own. And when the story goes badly, as it sometimes does, there can be alcohol and drug abuse, problems in the family and with the law, and at the worst, homelessness and even suicide.

The trouble with this bleak story is that it’s partly mythical and partly well- documented truth. And veterans despise it, because they both hate and fear what it says about them and their options. They also suspect that the rest of us either don’t care or don’t know how to help and end up afraid to try.

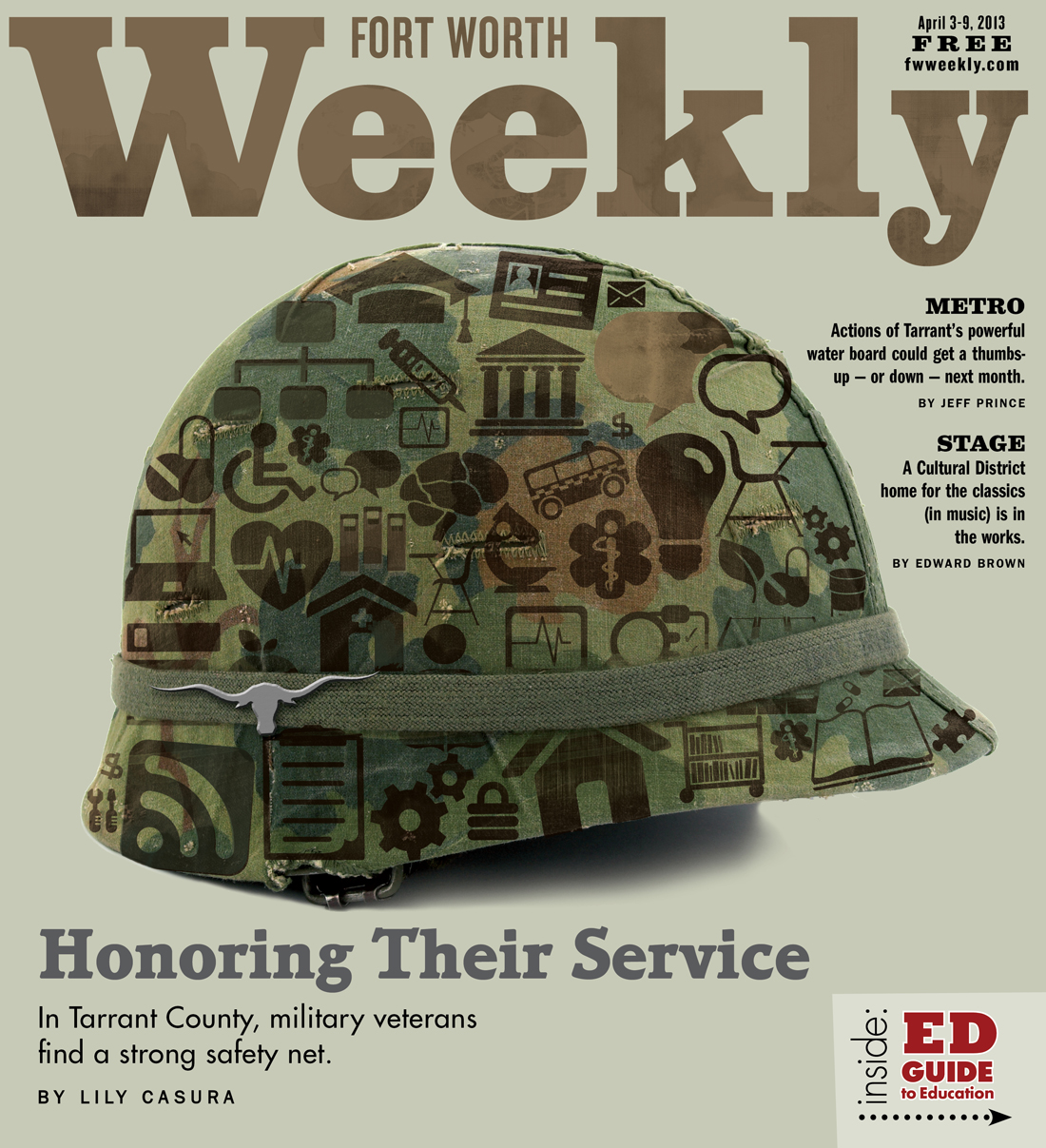

But here’s the good news: Military vets living in Fort Worth and the rest of Tarrant County are surrounded by one of the best and broadest support-systems safety nets in the country.

That wasn’t always the case. The helping network here has grown tremendously in the last few years, due to a lot of individuals and programs but in particular to people like Stevie Hansen, Tarrant County Criminal Court Judge Brent Carr, and retired Air Force Col. Kimberly Olson. It brings together an incredible range of services, including help with housing, counseling for men and women veterans and their families, and nationally recognized judicial services.

“I know we’re not the only place in Texas or the country that does this,” said Carr, who oversees a special court for veterans. “But by God, I’ll be damned if I know any place that does it better.”

********

“You can’t swing a dead cat in Fort Worth without hitting some organization that says it’s serving veterans,” said Olson, the charismatic, straight-talking CEO of women’s veterans group Grace After Fire, based in Fort Worth. “But I’d rather have the space for helping veterans be crowded, with lots of people trying to do good work within it, than have it be cavernous, with nobody there to help us.”

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is responsible for healthcare and benefits for qualified vets, but not every veteran is willing to walk through its doors. Some have had bad experiences with the VA, some aren’t willing to deal with the bureaucracy, and others –– especially women veterans –– say they don’t feel welcomed there, either by the staff or by other veterans who might question their service. Nationally, fewer than 40 percent of eligible veterans actually are enrolled with the VA, though the numbers are higher for troops who have served in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Olson has a strong opinion on what’s wrong with typical veterans’ mental health services, which she said have traditionally been “about what’s wrong with us.” She and other veterans resist and resent stories that paint all veterans as damaged goods, she said.

When veterans are told that enough times, she said, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: “When they look in the mirror, this is what they see.” That’s especially tragic, she said, because today’s relatively young veterans have long, potentially productive lives ahead of them.

When they first get home, most veterans just want to put their heads down, assume things are fine, and get back into civilian society. It’s almost a point of honor to do this, a longstanding military tradition that starts with the self-reliant “Army of One” philosophy taught in boot camp.

But at some point after they get home, almost a third of them acknowledge that they are dealing with post-traumatic stress. Even though there is still some delay in seeking help, current veterans are dealing with such problems more quickly and more fully than those returning from earlier wars.

The military itself contributes few resources for reintegrating troops after deployments. Fewer still are available for those who served in the National Guard.

Shari Julian, a licensed professional counselor in private practice, knows the military as a daughter, wife, and mother of active-duty military and veterans. Much of her work has dealt with mass trauma situations, and she has experience in counseling veterans.

“My experience in talking to them is, they come back thinking, ‘Thank God I’m home. I’m back!’ and they kiss the soil,” she said. “And then, nothing seems to go, automatically, the way that they think it should. And then nobody knows how to deal with them. It becomes more difficult for the families. The families get angry. At first, they’re sympathetic. They try to get them peer help, but then they wonder why they’re getting worse. And so it’s a progression –– but usually it’s not a progression up the mountain, it’s a progression down the mountain.”

Finding the services they need can be difficult. “It’s like putting together this patchwork quilt with a piece of this and a piece of that,” Julian said.

But in Fort Worth there are some excellent programs to help stitch that quilt together.

********

“It’s very much a community effort” in Fort Worth, said Hansen, the current head of the Veterans Coalition of Tarrant County, which began in 2011. Others involved credit the coalition with being at the heart of the veterans services scene. “It ‘takes a village,’ you know,” she said. “That’s what’s been astounding to me –– the community support for veterans and families.”

Hansen, 68, an engaging woman who clearly cares deeply about veterans, is also the chief of addiction services for Mental Health and Mental Retardation of Tarrant County. She got involved with veterans services four or five years ago when “a friend of mine at the VA said that we need a transitional living facility, specifically for people with mental health and substance abuse issues.” She and a team wrote a proposal and received a grant through the VA. Liberty House, a transitional living facility for homeless veterans, opened in March 2010.

Carr, who runs the Veterans Court and was the first head of the Veterans Coalition, said the coalition went from being “a loose association of showing up and sitting around a table with about eight people talking about veterans’ stuff, to about 50 or 60 people that show up” for a standing-room-only meeting.

“We’re going to be an agency that [focuses on] coordination and

best-practices advocacy — we’re really not going to compete with service providers,” he explained. “There are plenty of service providers out there. We’re going to try to make sure that a veteran has an easy path to figure out where he or she can go for the bundle of services that they need.”

********

Carr is a Marine Corps veteran, son of a World War II and Korean War veteran, with two sons in the Army himself, one in Afghanistan and one who served in Iraq. In addition to other voluminous duties, he presides over the Veterans Court, which meets every other week to offer veterans a diversionary path from the regular judicial system. When a case goes to Carr’s court, veterans who complete the programs he orders can get their criminal records expunged.

Veterans’ courts have their origins in the drug court model from decades ago and are part of the VA’s commitment.

“It’s the least [we] can do,” Carr said. “I can’t think of anyone more deserving of a second chance than a combat veteran.” Many who have served in the military see it as a matter of honor to try to clean up their records, he said, so that part is an easy sell.

He sees primarily misdemeanor cases in his court, with a few lower-level felonies. It’s mostly substance abuse that brings veterans to his bench. “Just like in regular society,” he said, “prescription drug abuse — when you’re trying to combat pain and such, and get hooked” — is a common problem.

The second most frequent problem is anger issues, he said, including bar fights, domestic violence, or “having an inappropriate response to people in public settings.” In many domestic violence cases involving veterans, “the family is still intact,” the judge said, “and there’s still love and hope, and a desire for the [veteran] family member to receive help.”

“I hate that it’s getting charged with a crime that is sometimes the wake-up call to veterans” that they need to get help, Carr said. “But frankly, that’s how many of them are going to get reoriented and partake of the services that they’re entitled to.”

********