When Allen and his girlfriend moved into their Austin-area house, a woman down the street passed out fliers warning neighbors that a monster had taken up residence. Their front door was egged, their cars broken into, and “people started crossing the street instead of walking in front of my house,” said Allen.

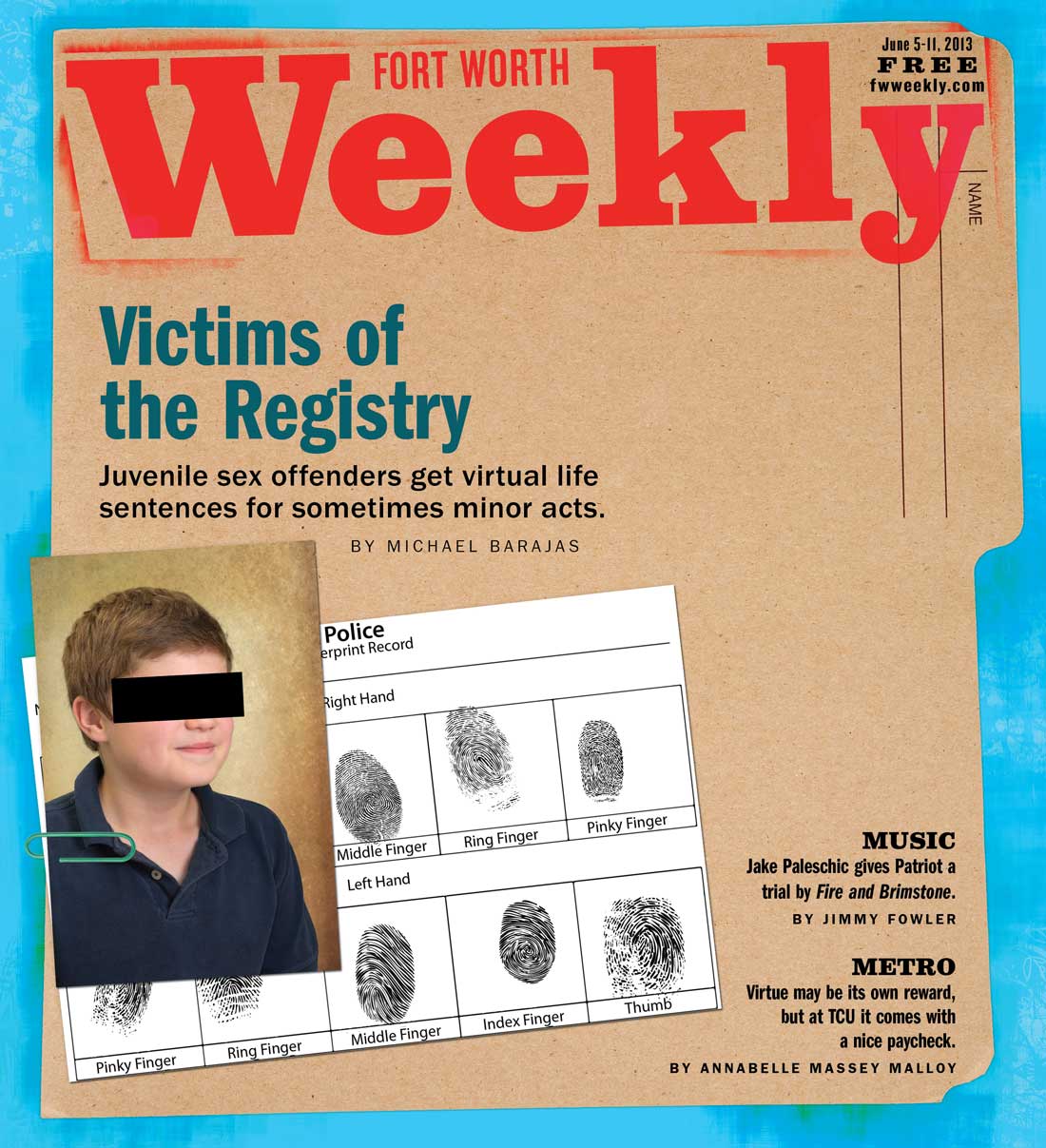

Allen spent much of his childhood in a Texas Youth Commission facility for inappropriately touching a 7-year-old family member; Allen was 11 at the time. He first registered as a sex offender with the Texas Department of Public Safety at age 20, when he was released from TYC after his incarceration for the offense. (Like most others interviewed for this story who were charged with juvenile sex crimes, he asked that his full name not be used.) If you looked him up on the state’s public sex-offender registry, you’d see the photo of a near-30-year-old convicted of aggravated sexual assault of a 7-year-old (any sexual assault against a child under 14 is considered aggravated).

Work has been hard to find since he got out of TYC — employers, Allen said, naturally shy away from hiring registered child molesters. When he signed up for classes at Austin Community College, the school displayed his information and photograph around campus as a warning to other students. Housing is difficult to come by.

“It’s a hard thing to explain to someone once they find out,” Allen told a reporter. “It’s like, ‘Hey, I’m not really this awful person. I just had a fucked-up childhood, I was punished, I’ve tried to deal with it, and I’m doing the best I can with my life.’ No one wants to hear that explanation. … It’s like I’m a leper.”

Texas is one of at least 10 states that put children found guilty in juvenile courts on public sex-offender registries. Texas has no lower age limit, but nationally, children as young as nine can be subject to registry laws. Adults who committed their crimes as children and served their time in juvenile facilities must continually update their addresses, workplaces, and photographs on the public registry. But the age of the victims continues to be listed as that when the offense happened. So each year, the apparent age gap between victim and offender widens. As of 2008, nearly 7,500 of the 54,000 offenders on Texas’ registry were there for offenses committed when they were children.

“Kids are getting lifelong punishment in juvenile court,” despite the fact that child sex offenders very seldom re-offend, said Nicole Pittman, a leading researcher on juvenile sex offenders and registries.

For years, Pittman has investigated what happens when states put child offenders on public sex-offender registries. She has interviewed nearly 300 youth offenders, many of them in Texas, along with defense attorneys, prosecutors, and even victims of child-on-child sexual assault. Based on her research, Human Rights Watch released “Raised on the Registry,” an extensive report that advocates removing children from public sex-offender registries.

Due to residency restrictions — originally meant to keep adult offenders from living near schools, parks, or anywhere else frequented by children — some child offenders can’t finish their education or even live with their families once out of youth lockup. Some families face retaliation and even threats of violence because their addresses appear on the registry.

Placement on the lists makes it difficult for former offenders to find stable housing, which in turn often leads them to run afoul of laws requiring them to keep their addresses updated –– and that lands many of them in adult prisons, sometimes for years. Such repercussions drive some child offenders to suicide, Pittman found.

“Juveniles need to be held accountable, but the punishment needs to be appropriate,” Pittman said. The report recommends that all juveniles be exempted from public registration laws, citing research that shows juvenile sex offenders are both the least likely to re-offend and the most likely to respond to treatment.

The registry requirements affect child offenders in many states. The laws and enforcement in Texas are among the harshest, Pittman said –– but there’s plenty of competition.

Not everyone agrees with that characterization. Riley Shaw, head prosecutor of juvenile cases in Tarrant County, said he believes Texas’ sex-offender registry law is one of the most progressive in the country regarding juveniles, following changes that were made about a decade ago to address some of the same situations that Pittman’s report documented.

Pittman’s is the first study of its kind investigating the effects of the sex-offender registry on juveniles. She has testified before Congress and before legislative committees in more than two dozen states. She said the idea of reform of registry rules involving young offenders is gaining traction, even from conservatives.

Unlike with minors charged with assault or even murder, she said, “When you put a child who commits a sex offense on a public registry, that’s a virtual life sentence.”

********

Child protection workers visited Dominic’s San Antonio home when he was 15, following a domestic dispute between his mother and her partner. That’s when they first heard of allegations that Dominic had molested his sister when he was 13 and she was 11.

Dominic spent much of the following year in and out of psychiatric treatment, diagnosed with ADHD and bipolar disorder, his grandmother said in a recent interview. Dominic denied the allegations, but he was eventually convicted of aggravated sexual assault of a child and placed in a TYC facility.

His mother died in a car crash while he was in custody.

Dominic was released from TYC, put on strict parole, and moved into an apartment by himself on San Antonio’s East Side when he was 19. He couldn’t live with his grandmother, who had custody of his sister, the victim.

Last month Dominic’s sister signed an affidavit claiming he never molested her, saying she was coerced into making the allegations. Dominic was arrested last month and remains in jail for violating his parole by failing to participate in his treatment program, which requires that he discuss the assault in explicit detail, his grandmother said.

In the past year, Dominic has twice slit his wrists.

“He doesn’t see any way out,” his grandmother said in a tearful interview. “He says, ‘I don’t have a life anymore, Grandma. Everybody treats me like I’m a beast, like I’m an animal. They wish I was dead. I wish I was dead too.’ ”

The Human Rights Watch document includes the stories of other juvenile offenders who attempted suicide — including three who succeeded. One, a 17-year-old from Michigan, took his life months after the state passed a law to remove offenders from the registry who were younger than 14 at the time of their offenses.

“Everyone in the community knew he was on the sex-offender registry; it didn’t matter to them that he was removed,” his mother told a Human Rights Watch researcher. “[T]he damage was already done. You can’t un-ring the bell.”

Pittman said her research showed that registration laws, which require placing offenders’ photographs and personal information on online registries, also make juvenile offenders and their families targets for harassment and violence.

Josh Gravens was 12 when he had sexual contact with his 8-year-old sister. When his worried mother sought help from a Christian counseling center near the family’s home in Abilene, the center reported Gravens to authorities for sexual assault of a child — by law, it was required to do so. Gravens spent three years in a TYC facility. When he got out, he was allowed back into his parents’ home, with his sister, but authorities required his parents put alarms on his windows and a lock outside his door.

When Gravens started classes at Texas Tech University, he got death threats. People threw beer bottles at him in the campus parking lot. He eventually dropped out of college.

Last year, hoping to move out of a family member’s home, Gravens looked for a place to live with his wife and their four children. “We tried like 20 different apartment complexes. All told me no. It was because I was on the registry,” Gravens told a reporter. Managers at two apartments last year gave him abrupt notices to vacate after he’d moved in.

Last November Gravens showed the judge who sentenced him a Texas Observer article from last year that detailed his story. The judge removed him from the list. Though off the registry, Gravens still has two felony convictions for failure to register on his record — both, he claims, the result of not being properly told about the reporting requirements.

“I’m off the list, but there are still repercussions that will follow me the rest of my life,” Gravens said. Those felony convictions “still limit what I can do, and they never would have happened had I not been placed on the registry as a child.”

********

I would like for Assistant D.A. Riley Shaw to know that whatever changes were made to Texas law 10 years ago did not make Texas a more progressive state when it comes to juveniles and sex offenses. Who is he kidding? That Perry appointment must have gone to his head. The truth is Texas has no mercy once a person has been accused of a sex offense, regardless of age or the actual incident.

“Once you are on a publicly accessible registry, your life is pretty much shot.” — Sen. Bobby Scott at the AWA Reauthorization Hearing

The registry is barbaric for anyone listed on it, but it is especially heinous for teenagers, who are ill-equipped to handle a fate worse than death.

I agree. I am with a guy that poses no threat toe children. He has to be on the registry cause he looked at porn and a website popped up and there was an underage girl (16) on there. The people that are making these sites need to be put away.

Just saw this too. There is still hope. http://www.defenselawyer.net/sex-offender-deregistration

I read that article & it really makes you wonder what lawmakers & judges are thinking when they put kids as young as 9 on a sex offender registry. When I think back to my childhood, any number of boys who wanted to play “you show me yours, I’ll show you mine” would have been ruined for life under this current system! Also the girl who was convicted as an adult of distributing child porn when the child porn in question was pictures of herself is absolutely tragic injustice. The judge who convicted her & put her on the registry as well as the DA who brought the charges should lose their bar cards for being too stupid to be on the bench or representing the public. There seems to be very little common sense being used in law enforcement these days.