Does Bob Dylan do it for you? I ask only because I keep hearing that people either love him or hate him. I guess I’ve always been hovering somewhere in the middle –– not anymore, though.

The 75-year-old native Minnesotan was just awarded the Nobel prize in literature, a distinction that had not been afforded to an American since 1993 (Toni Morrison) and that had not been bestowed upon a writer of song ever. In response, Dylan did what any red-white-and-blue-blooded American artiste would do: nothing.

Or next to nothing. On the afternoon of the announcement, Thursday, Dylan’s social media team posted on his Facebook page: “Bob Dylan was awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature ‘for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,’ ” quoting the Swedish Academy, the stewards of the prize.

And that’s it.

At the time of this writing, the post had been liked by “Bob Dylan,” “Steel Pulse,” “Alfonso André,” and 86,124 others. It had been shared 7,836 times.

And there the post has been sitting, right beneath a shrill link to Amazon.com’s page for the forthcoming release of his 1966 live recordings.

Accidentally or not, Dylan via his social media team made winning the prize seem like only a medium-hot achievement. Like getting a short story published in Fence. Or nabbing a speaking part in an E.D. commercial.

But maybe that’s the point. Dylan has not returned repeated attempts by the Swedish Academy to congratulate him and to invite him to the big party they’re throwing him and the other winners. Maybe by being chronically unavailable Dylan is issuing a statement about the condition of American letters, that we’re not as bad as the Swedish Academy clearly thinks we are.

The rap against the academy’s literary folks is that they opt for social meaning more than writerly talent. Nothing else explains why the world’s greatest living novelist, Thomas Pynchon, and before he died in 1998 the world’s second greatest, William Gaddis (who may or may not still be Thomas Pynchon, who may or may not be a secret group of famous writers working collectively), have not been honored and also why the greatest contemporary wordsmith in English, the dearly departed John Updike, was also snubbed. So screw you, Swedes, Dylan seems to be saying. And I couldn’t agree with him more. Pynchon rules.

I’m probably wrong about what Dylan’s Facebook gurus are thinking, but if I’m right, I don’t think I’d mind being lumped in with the lovers of the guy. I won’t go as far as to go see him Saturday at the WinStar casino. I’m broke, for one thing. For another, I’m totally broke. And I won’t be buying any of his music anytime soon. Most of it is a little too drone-y and same-y for me. As a semi-literate ape, I do enjoy the occasional enlightening turn of phrase. Tell me: Where can I buy a book of Dylan’s new poetic expressions?

I blame my upbringing for my clearly unrefined musical palate. I grew up lower middle-class in a cold, dreary Rust Belt city in the early ’80s, when MTV had just exploded into living rooms across the nation, turning every one of us born between the late 1960s and mid ’70s into easily dazzled zombies who are still struggling through this morass we call life. To us, your music either rocked (or rapped), or it sucked. Dylan’s music sucked. Granted, all we knew of him was that “everybody must get stoned!” song that would pop up on the classic rock radio station every March and April (tax season) and that video of that skinny white dude in an alley flipping cue cards baring the lyrics to the rapid-fire tune playing in the background.

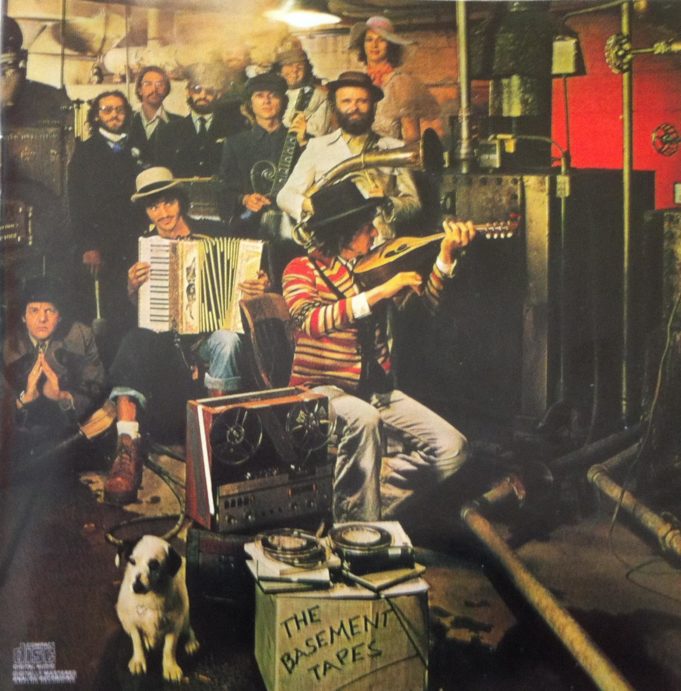

I didn’t fully realize who Bob Dylan was and what he represented until years later, after I finally gave in to the purple mainstream media noise about him and read Invisible Republic. This was back when I loved writing and wanted to be a writer but didn’t know good writing from bad –– glad that that Greil Marcus cat turned out to be a worthy influence. The main tenet of his book appears to be Dylan’s relationship, intentional or accidental, to Harry Smith’s anthology of American folk music, a collection from the 1920s and ’30s re-released in box set form in the same year as the book’s publication, 1997, several months before I washed up on the shores of graduate school (and a year before William Gaddis would die). Without any money to pay for ramen noodles let alone a sprawling box of several dozen songs, I spent countless hours in the school’s music library listening to all six of Harry Smith’s CDs. I also listened to The Basement Tapes, the focus of Marcus’ book and the lens through which he evaluates Dylan’s oeuvre. And perhaps true to the author’s theme, Bobby indeed could have been conjuring up the spirits of yesteryear’s Appalachia, where most of Smith’s subjects lived and were recorded by him. Maybe not, but while I’ve read hundreds of books and listened to hundreds of albums since the late 1990s, I still have a fondness for “Yazoo Street Scandal” and a few other Basement Tapes tracks. And for Clarence Ashley’s “Coo-Coo Bird,” but that’s a whole other story.

Despite my intellect or lack thereof, I’m as open now as I’ve ever been to smart tuneage. I’m exploring Dylan to see if I’ve left anything behind.

Apparently, what I’ve been missing this whole time are his lyrics.

I’ve heard them in the context of songs, and they seem just fine, but I haven’t read them the way I would Pynchon or some of my favorite poets (Jorie Graham, W.S. Merwin, John Ashbery) and literary magazines (Ploughshares, Sleepingfish, um, Fence).

Billy Collins, a former U.S. poet laureate and the source of some bile for his easy, populist, non-Dylanesque style, believes Dylan isn’t just a songwriter.

“Most song lyrics don’t really hold up without the music, and they aren’t supposed to,” Collins recently told the Times. “Bob Dylan is in the 2 percent club of songwriters whose lyrics are interesting on the page even without the harmonica and the guitar and his very distinctive voice. I think he does qualify as poetry.”

We’ll see, buddy. We shall see.

Tickets to Saturday’s WinStar show are $75-150. Prize money awarded to Bob Dylan for his Nobel win is $930,000. A lot of moolah but not quite a million dollar bash.