At approximately 3 a.m. Sat., July 20, 1895, a terrifying explosion occurred two miles southeast of Mart, Texas, 20 miles east of Waco and barely across the Falls County line. The sound was heard from 10 miles away, and the people of Mart dressed quickly and went out into the night to determine the origin of the blast.

Emmett and Prince Elliott and J.C. Douglass saw smoke and flames in the distance. They were reportedly the first to arrive at the scene of the carnage and could scarcely believe their eyes. The debris radius was lit by human candles — human corpses on fire.

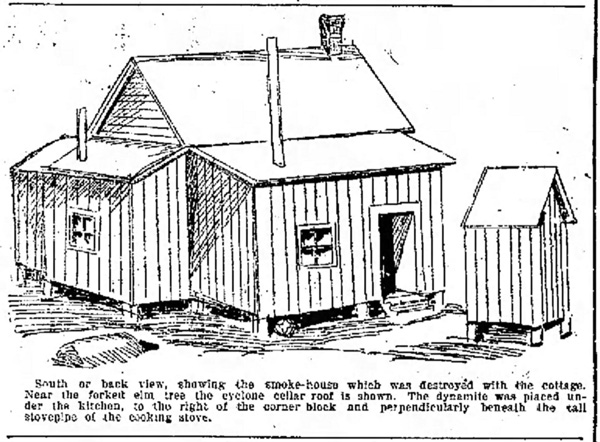

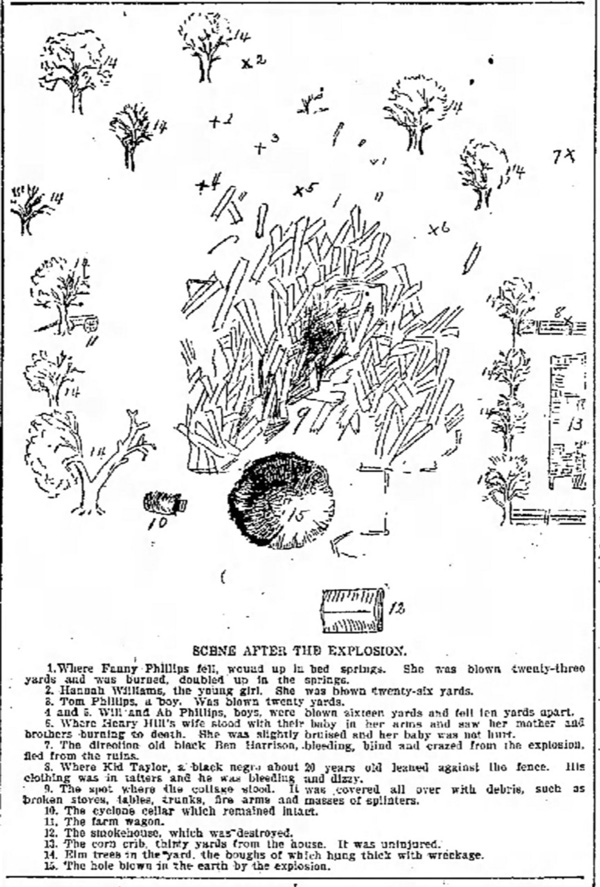

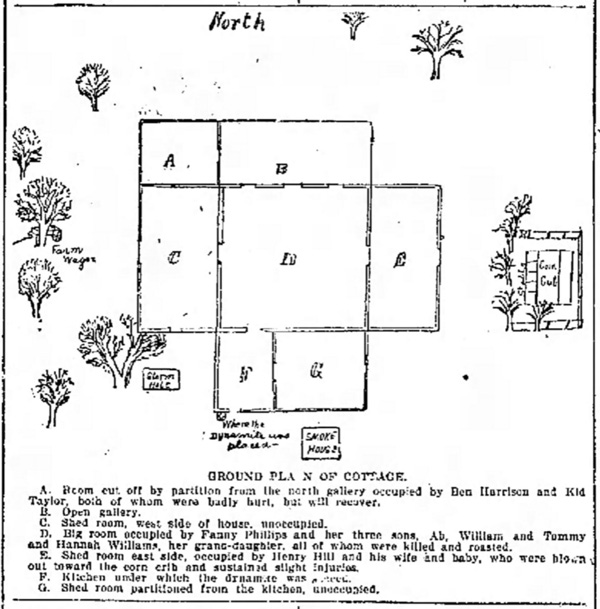

What had been a familiar house owned by a respected Black family was now a smoldering crater. A partially denuded Black woman was walking around with a baby cradled in her arms. A young Black male hired-hand was leaning against the remains of a structure, bloody and inarticulate. The bodies of Mary “Fanny” Phillips, her three sons — Tom, Absalom Jr., and William — and Hannah Williams, her granddaughter, were scattered across the area wrapped in flames that emitted an unspeakably grotesque light. Fanny’s body was knotted up in her bedsprings, her knees touching her chin, her entire figure “baked and shrunken.” Fanny’s brother, Ben Harrison, was found several hundred feet away, blinded, maimed, half-naked, and “incoherently muttering.”

Fanny, Tom, Absalom Jr., William Phillips, and little Hannah Williams were “Blown to Eternity” by a significant quantity of dynamite, and their white neighbors in Mart were shocked.

Photo by E.R. Bills

*****

During a break in my writing schedule in 2017, I decided to pursue a story that had bothered me for a couple of years. It involved the abovementioned act of terror in Central Texas, but it was based on secondary and tertiary sources and seemed to have vanished from local histories. In my wheelhouse, for sure.

But just because you go looking doesn’t mean you’ll find anything. It was a fishing expedition, but I didn’t get a single bite. The incident — or series of incidents — was so old and buried, it might as well have never happened.

Texas is funny like that.

In 2017, I tried unsuccessfully to pinpoint the exact location of the former Phillips place but had no luck. Then I stopped by the Nancy Nail Memorial Library in Mart and spoke with a white librarian and a white patron who had lived in the town for decades. I explained to them what I was looking for, and they seemed surprised. They said they had never heard of the explosion. In fact, they wanted copies of what I had so they could start a folder on it in the library. I obliged them, and the librarian gave me the name of the oldest living Black citizen in the community and said I should contact her. I did, but she was also entirely unfamiliar with the incident. She’d never heard anyone — Black or white — ever mention it.

It was one thing to go into a community and remind them of something that had happened because they had denied it happened or covered it up. This was obviously different because Mart didn’t have a reputation like Palestine or Slocum or even the nearby McLennan County seat, Waco, where two Blacks had been burned at the stake, one in front of a cheering white crowd of thousands (while the mayor and police chief watched on) and chronicled in photographs that became popular lynching postcards.

Mart seemed like a nice town, and I was confronted with a small community that wasn’t actively engaged in conspicuous obfuscation. Would exposing a local atrocity improve race relations or make them worse? They seemed fairly good already. Would writing about this incident foster a kumbaya moment or create racial resentment where there seemed very little to speak of?

I decided then, if nothing else, I would err on the side of the truth — so far as it could be known.

*****

As it turned out, the origin of the July 20, 1895, blast stemmed from an incident three months prior, on April 17. Here is a published account dated April 18, 1895, in the “Budget of News from Waco” section appearing in the Fort Worth Daily Gazette the following day.

Further particulars and details of the tragedy near Mart yesterday evening have been received and show it to have been a most fatal one. Two men are dying and the third is fatally wounded. Phil, George and Ned Arnold, brothers, are young farmers living at and near the tragedy. It seems that Ned Arnold recently brought to the neighborhood several young negroes from Arkansas for farm work. At present he had no work for them and he had told his brother Phil that he might secure the negroes to work for him. One young negro of the party had become a friend of Abe Phillips, a negro farmer of the community, and the latter sought to prevent the lad from going to work for Phil Arnold. After several ineffectual attempts to secure his services, Phil and George Arnold and Watts Vaughn at noon yesterday went to Phillips’ house to induce the negro to work.

They were unsuccessful and as they were leaving, Phillips followed them. When about 600 yards from his house he was heard to say: ‘G—D yes, and I’ll shoot you.’ He immediately opened fire on Phil Arnold with a revolver and had fired two shots without effect when Arnold brought his revolver into play and fired four times, putting as many bullets in the negro’s body, one through the stomach and three in the head.

When Phillips opened fire, Richard Bragg, a negro, in front of whose house the shooting occurred, began firing at Ned Arnold. The latter returned the fire and Bragg was shot in the wrist and through the bowels. His wound is fatal.

A few moments after Phil Arnold had shot Phillips, the latter’s son, Wes Phillips, a boy of 17 or 18 years of age, [quietly] walked up and emptied the contents of a double-barreled shotgun into Phil Arnold’s back, killing him almost instantly.

The negro lad made his escape and he immediately sought the officers of [Falls County] to give himself up, fearing lynching at the hands of Arnold’s friends. He reached Reisel last night and was turned over to the sheriff of Falls County and jailed at Marlin.

The community in the neighborhood of the tragedy is greatly excited and deplores the affair.

The Arnolds are said to be highly respected and peaceable young men, while the negro Phillips, who was killed, has always been considered a troublesome character.

Virgil Gillespie, a young farmer and neighbor of the Arnolds, arrived in [Waco] this morning to purchase burial clothes for the body of Arnold and told the story of the tragedy to the reporter.

It was the longest report I could find on the incident. The Galveston Daily News account, also from April 19, provided one more salient detail: “The trouble resulted from a bound boy who ran away from Arnold.”

“Bound boy.”

Not a term I was familiar with, so I looked it up.

Obviously archaic, “bound boy” referred to someone who was often sent or taken from an orphanage to become an “indentured servant.” This would primarily refer to a white child, not a Black slave or, arguably, even a recent descendant of slaves so soon after Reconstruction in Arkansas, Texas, or any other area in the former pro-slavery South. Slavery-like conditions still existed. Did Phil Arnold bring “bound” Black boys (or men) from Arkansas to work for him? Did Abe Phillips unintentionally or intentionally attempt to nullify this illicit and possible criminal agreement? Or did one of the Blacks Arnold brought down from Arkansas simply decide he no longer wanted to work for him? Texas wasn’t a “right to work” state back then, any more than it is now, but it was much worse for Blacks. That’s why so many migrated north.

Whatever transpired to deliver three “bound” young Black men to the Mart area, Abe Phillips apparently intentionally or unintentionally complicated the agreed-upon — or forced-upon — terms. And the resulting confrontation was deadly.

Courtesy Galveston Daily News archives

*****

Almost three months to the day after the altercation is when someone detonated explosives under Abe Phillips’ widow’s house. It disturbed the Mart community.

Before the sun rose, hundreds of people on the ground gazing with awe at the horrible scene in which a household had been annihilated with dynamite in an explosion so terrific that doves, scissor tails and mocking birds roosting in the elms had not only been killed but picked clean of feathers, and a six-room cottage had been effaced and no fragment of it left too large to go into an average heating stove. Wherever one goes in the precinct, whatever group he joins, he finds the explosion under discussion. In the fertile valleys, the crops are laid by and the affluent farmers have organized protracted meetings where eloquent ministers are administering spiritual pabulum to large congregations, but in the intervals, the congregation scatter under the shade trees, turn their faces toward the Smith-Strange farm [where the Phillips family resided], and talk about dynamite.

Commenting on the local produce, a Black woman said that “things don’t taste right ’round here” anymore, and the more superstitious elements of the African-American community believed a “supernatural agency was involved.” They claimed ghosts wandered among the elms and shrieked through the night in the rows of cotton.

On the evening after the Phillips house was destroyed, three Black men were fired upon when they attempted to retrieve a wagon, presumably to help clean up the destruction.

The people of Mart were indignant. And the onlookers of the aftermath did more than gather souvenirs. They helped treat the wounded, assisted in burying the dead, and held a public meeting to condemn the atrocity, even drafting a resolution.

Whereas, a … crime was committed in our community on the night of the 20th instant in the massacre of a family of negroes, some unoffending children being in their number, by the use of some explosive substance, causing the instantaneous death of five persons and seriously wounding two others, and the following night some negroes proceeding upon the public highway were fired upon, as we believe, with intent to kill, and

Whereas, such unlawful acts are calculated to tarnish the fair name of our community and thus deter good people from settling among us, be it

Resolved, that we citizens of Mart community, in mass meeting assembled, desire to express our total disapproval and condemnation of such unlawful acts and deeply deplore their occurrence in our midst, and we invite and demand the fullest investigation of the affair by the proper authorities, and we promise any assistance that may be within our power to enable the officers to bring the criminals to justice.

Resolved, that a petition to the governor of the state, signed by the members of this meeting, be forwarded asking that a sufficient reward be offered to induce a first-class detective to penetrate the mystery that seems to surround this affair.

In the days that followed, it was discovered that a child had died in the Phillips house on the Thursday before the explosion, and while the Phillips family was at the child’s funeral in Harrison (eight miles both north of Mart and southeast of Waco), the Phillips family’s “watch dog” was poisoned. Then, after the explosion, which spread debris over 75 acres and blew the Phillips’ smokehouse to smithereens, local dogs who partook of the scattered Phillips bacon store got sick, and some died. One local doctor said the “atmosphere around the Phillips premises was pregnant with death.”

The perpetrators of the atrocity didn’t leave anything to chance. If there were any questions as to whether a white life mattered more than a Black one on July 20, 1895, the answer at the Phillips residence was resounding. And one local white man, again, described the ghastly carnage. “There they lay, scorched and burning, their eyes starting, grinning as if in horror, mutely detailing the story of an outrage which I hope will stand alone in the annals of Texas crime. I hope the man who did the deed saw his handiwork as I saw it, and I’ll warrant he will have it visit him in his dreams — that old mother roasting, coiled in red hot steel springs and beside her brood of children! I tell you it was worse than pen can portray it.”

The undertaker had problems getting the grotesquely contorted corpses into coffins. The funeral march to Harrison was haunting and somber. Then several black families fled the area. It was said that the “dreadful explosion” would “stand as a mark of happenings in the Mart region. ‘This thing happening before,’ and the other thing ‘after dynamite night’ will be fixed sayings with both white and black in that country.”

Courtesy Galveston Daily News archives

*****

I couldn’t find any evidence of the old Phillips place or anyone, Black or white, who knew anything about it.

As I wandered through the somewhat overgrown old Goshen African-American Cemetery on the corner of a bend in FM 1860 in the old Harrison station area, looking for the graves of the atrocity’s victims and that of Abe Phillips, I kept thinking about a metaphor in Booker T. Washington’s Atlanta Exposition Speech, two months (September 18, 1895) after the retaliatory attack on the Phillips family. Washington probably didn’t know about Mart area barbarity, but still.

A ship lost at sea for many days suddenly sighted a friendly vessel. From the mast of the unfortunate vessel was seen a signal: ‘Water, water; we die of thirst!’ The answer from the friendly vessel at once came back: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ A second time the signal, ‘Water, water; send us water!’ ran up from the distressed vessel and was answered: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ And a third and fourth signal for water was answered: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ The captain of the distressed vessel, at last heeding the injunction, cast down his bucket, and it came up full of fresh, sparkling water from the mouth of the Amazon River. To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land, or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next door neighbor, I would say: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ Cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded.

Washington’s comments were optimistic about progress, hopeful and practical. And probably useful to many. I wish more Texan members of the “friendly” vessel had bought in.

All I discovered (and carefully avoided) in the Goshen Cemetery was snakes. Then I drove around and eventually spotted an elderly Black man opening his chain-link fence driveway gate. I asked about the local Black graveyards and particularly the one in Old Harrison. He confirmed that it was the Goshen Cemetery and said he tended it when he had the time. I asked him if he’d ever heard of the explosion south of Mart, and he said he hadn’t. I asked him if he had seen headstones for members of the Phillips family sharing the same date in 1895, and he said he wasn’t aware of any.

There was no fixed memory of the act of terror that befell the Phillips family in 1895 and no sign of their remains. The local judge and law enforcement officers at the time of the incident believed hostile neighbors blew up the remaining members of the Phillips family to avenge the death of Phil Arnold, but no one was ever arrested, charged, or prosecuted for the atrocity. West Phillips was apparently acquitted for shooting Phil Arnold, and Richard Bragg’s wounds were, in fact, not fatal. Bragg moved to Waco, but both reportedly spent the rest of their days dodging assassination attempts. In fact, an attack on Bragg’s new residence was reported in the August 16, 1895, edition of the Galveston Daily News. Bragg survived once more, and the culprits behind the ambush were never apprehended.

Texas is funny like that: long and tall on every myth and stray scrap of charming rustic lore but short on remembering (much less owning up to) obvious mistakes and monstrosities.

The Lone Star State is parched in more ways than one.

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is the award-winning, bestselling author of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas and Tell-Tale Texas: Investigations in Infamous History.