Planning to make a nice Mother’s Day meal for my wife, Patrice, and my mother, Kathy Flories, I went early to the local grocery store hoping to beat the inevitable Mother’s Day rush as last-minute folks grabbed flowers, cards, and desserts for their usually neglected mothers. I pulled into the parking space at Walmart, and my phone dinged. Thinking it was my wife asking me to purchase some afterthought, I checked my phone. It wasn’t from Patrice at all. I was surprised to see the name Rob Hauschild, the head of Wild Eye Releasing, a man who has distributed several of my movies. The text was brief. It read simply, “Roger Corman R.I.P.”

Wow. The guy I thought might never die had finally passed away at the age of 98.

Roger Corman, my role model as a schlockmeister and, for a brief time, my acquaintance and employer.

I first became aware of Roger Corman, in a very vague way as a name in the credits of some of the movies I watched on TV, when I was only 4 years old. I was the child of teenage parents, one of the original monster kids of the 1960s, a boy who spent a minimum of five hours a day in front of the boob tube. My folks were struggling, and the TV was the cheapest babysitter. I was drawn to anything that could be called scary, especially anything involving monsters. I was in love with all the Universal monster flicks, but I loved the cheesy A.I.P. movies, too. Invasion of the Saucer Men, It Conquered the World, Not of This Earth, Attack of the Crab Monsters — these films found a lasting place in my young mind even before I was old enough to attend school.

Just a few years later, when I started attending the local theater every Saturday, I fell in love with Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe movies. The Raven, Fall of the House of Usher, The Haunted Palace, Masque of the Red Death — I loved these films. They weren’t quite as good as those great movies coming from Hammer Studios in Britain, but they were close. Since they were replayed often at various theaters in Fort Worth, I saw them repeatedly, especially when they were grouped into triple and even quadruple bills every Halloween.

My enthusiasm for horror films was boundless by the time I graduated elementary school, and I suppose my passion was infectious. Every time I made a new friend, they became fans of the genre as well. My buddy John Shults started attending horror flicks with me on a regular basis. After I read about some kids my age making a monster movie with 8mm film in New York, I became convinced filmmaking was my calling. My friends — John Shults, John Cottrill, Zeke Zelazny, Bill Hobbs, and others — began helping me make 3- and 6-minute epics in the eastside neighborhood around our house on Meadowbrook Drive.

“Do you really think you can be a film director? I mean, professionally?” John Shults asked me one day.

“Sure,” I replied. “Why? Don’t you think I can do it?”

“I can see you as another Roger Corman, but you’re no Cecil B. DeMille.”

I took what he said as a compliment. Who the heck wanted to be Cecil B. DeMille in 1970? Not me. Roger Corman? Hell, yes!

Photo by Peggy Mitchell

I studied filmmaking. I married. My life had the usual ups and downs. When I was living in Hawaii for a year, ostensibly saving money to go to film school in Santa Barbara, one day I looked up Corman’s name in Who’s Who in America. I saw that he would soon turn 50 years old and that his birthday was approaching. I bought him a birthday card and mailed it with a short note to the address listed in Who’s Who, a place on Sunset Boulevard. The card came back to me as undeliverable because it did not include a suite number. How does that happen? I wondered. Surely, the mailman who delivers that route knew who Corman was and had delivered other mail to him. I was bummed.

Time passed. I attended Brooks Institute’s motion picture production classes. My wife and I wanted kids, but we didn’t really want to raise them in Los Angeles, so we moved back to Texas. Just before I made my first feature film, in 1984, I rented a print of Roger Corman: Hollywood’s Wild Angel, the documentary by Christian Blackwood, and had a public screening on Lower Greenville in Dallas at a bar called Tahiti’s, which was owned by my attorney Bill Wray. We invited Roger Corman, Larry Buchanan, and Tom Moore (a local film distributor) to attend. Roger politely declined, saying he would be in South America, where he was busily exploiting the Latino B-Movie market. Larry Buchanan came, though, as did Tom Moore. In the following years, I developed friendships with both of them.

I made movies. Down, dirty, and cheap, eager to cash in on the VHS home video phenomenon that had replaced the drive-in theaters as the place where you sold those cheesy movies that couldn’t find a home in more respectable venues. Jane Sumner, who had a column in one of the Dallas papers, did a piece on me and called me the “Roger Corman of Dallas.” Shortly after that, Texas Monthly did a nice piece on me. It seemed I was on the way to carving out a place in the movie business.

Sometime in 1994, I made a deal with John McCarty to turn his book The Fearmakers into a 13-part series. One of the episodes centered on Corman, and through an L.A. contact, Ted Newsom, we landed a nice video interview with Corman. Corman was gracious and poised on camera, as always, and we considered it a coup, getting him for our program, even though Ted, as director of that interview, completely botched it by not following my instructions.

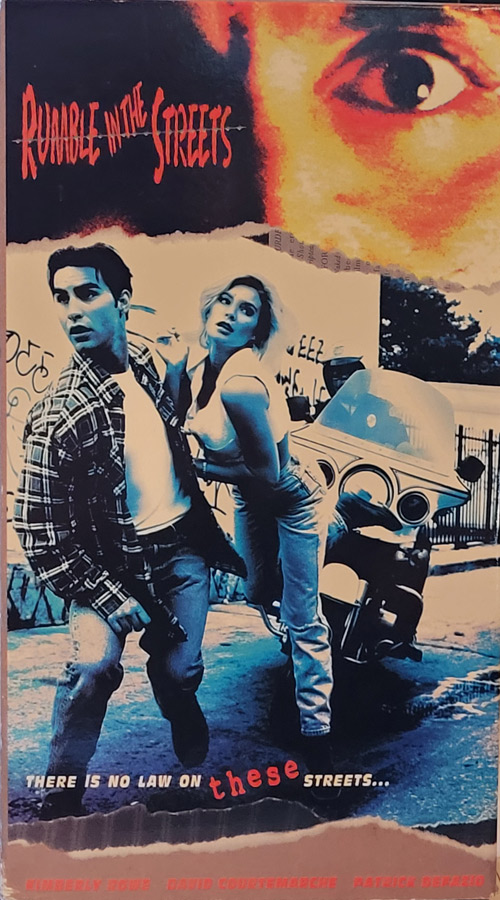

A shyster businessman from Dallas courted my participation in a company he was starting. He wanted to make movies. Together we made several movies in 1995. After making four movies by September that year, I contacted Roger Corman with a plan to squeeze in one more production before the year ended. He responded quickly and gave me a project called Rumble in the Streets to shoot in Fort Worth in December 1995. I was in heaven. My childhood dream of making movies for Roger Corman had come true.

Corman came to town for a couple of days to see our progress on Rumble in the Streets and to touch base with the Dallas film commission. My understanding was that he contributed generously to the film community in Texas. He took me, the D.P., and the two leads of the film, David Courtemarche and Kimberly Rowe, out to eat at The Balcony on Camp Bowie. It was great. Roger was affable and gracious and made us all feel like pros.

Later, in September 1996, I made a second film for Corman called The Protector starring Lee Majors and Ed Marinaro.

Other filmmakers, people from California who had had dealings with Corman, were amazed that he had actually given me money to do two films.

“He gave you money? Really?”

Evidently, he was not known for actually footing the bill, even for filmmakers more experienced than myself. I had to feel good about that. I did feel good about that.

1996 was a major turning point for me, the beginning of a period I refer to as my personal shitstorm. My marriage of 18 years ended, both my grandmother and my father committed suicide, Tom Moore filed for bankruptcy, owing me a lot of money, my son Joshua died in an accident, and I foolishly descended into a nightmare of alcohol and drug abuse. I abandoned my film career until 2020, when interest from Wild Eye and other distributors kindled my desire to dabble in movies again. When these guys interviewed me for special features for re-releases of some of my old movies, they were always impressed with the fact that I’d made movies for Corman. I’m a little impressed myself, that a working-class kid from Fort Worth declared at the age of 12 that he was going to make movies for Roger Corman, and, by God, he did.

Thank you, Roger Corman, for setting trends, breaking records, influencing popular culture, and just plain entertaining Americans for decades. You left an indelible mark on my life. I appreciate your accomplishments, and I’m glad to have worked with you. Rest in peace.

Bret McCormick is a writer, artist, and filmmaker who has lived most of his life in Fort Worth. He produced, directed, and wrote his first feature film, Tabloid!, in 1984. Since that time, he has been a critical player in the production of more than 20 feature films and has written or edited more than 12 books.