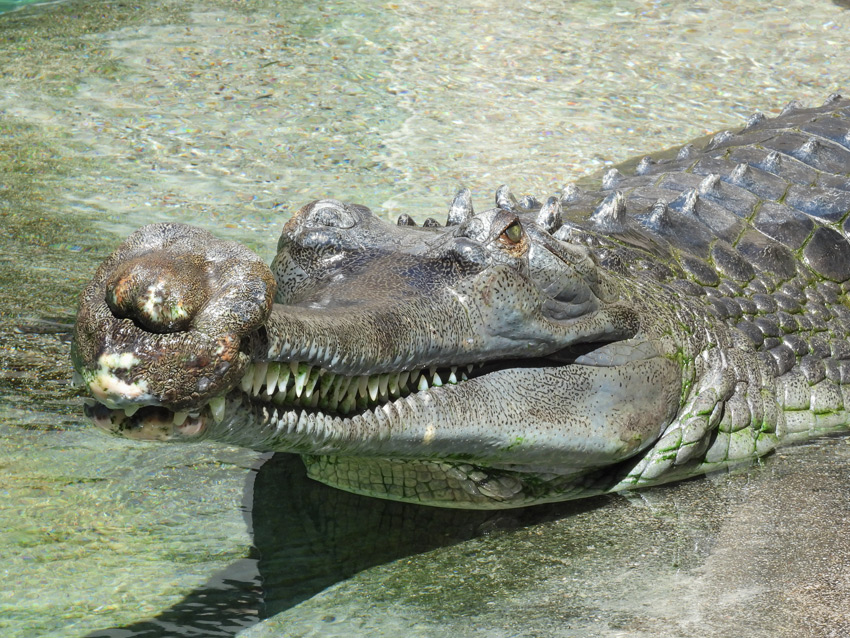

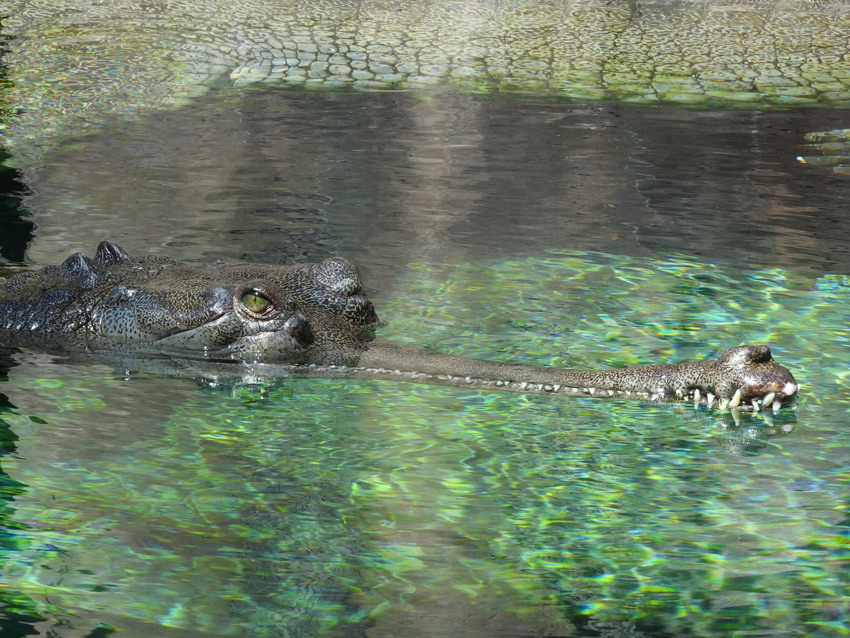

Ripples barely move across the water as giant crocodilians glide effortlessly just beneath the surface. Like ghosts from a prehistoric age, the gharials are graceful, unsettling, and sneaky. Despite their size — males can grow to 16 feet long and weigh 1,500 pounds — they move with impressive stealth. Unlike some apex predators, gharials are not fast, flashy, or loud. I found them intimidating simply because they seem to be very observant and have a long snout filled with over 100 razor-sharp teeth.

From a protected training area at the Fort Worth Zoo, I recently watched the gharials arrive in eerie precision. A gharial’s long, narrow snout quietly sliced through the water before its reptilian green eyes emerged and locked onto mine. Two zoo staff members and I were not in any danger. Gharials do not view people as a food source. Their long, slim snouts and many teeth are used to hunt and eat fish. Still, the massive creatures require considerable respect and safety measures when they are nearby.

In the wild, it’s gharials that are in danger. The species, one of the largest crocodilians in the world, is listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This means they are at a heightened risk of becoming extinct. Fewer than 1,000 gharials are believed to remain in the wild.

A 15-year-long gharial conservation program at the zoo is part of a global race to try to save them. Among North American institutions, the Fort Worth Zoo remains the only one to both produce multiple gharial offspring and repeat the process over multiple consecutive years. Gharial hatchlings born on June 5 and June 11, 2025, have joined others from 2023 and 2024, making for a total of five at the zoo.

Photo by Teri Webster

“To have continued success for a third year in a row means that in addition to having more of these beautiful and imperiled crocodiles for the future of the species, we are able to further refine our breeding, incubation, and hatchling husbandry techniques as each year informs us more and more,” said Vicky Poole, associate curator of ectotherms at the Fort Worth Zoo, in a statement.

The tiny crocs currently remain behind the scenes, but the zoo hopes to create a place where they can eventually be seen by the public. That is still in the planning phase.

Part of the zoo’s success with gharials is attributed to a habitat in the MOLA (Museum of Living Art) that is specifically designed for their conservation, care, and breeding, said Zac Foster, supervisor of ectotherms for the zoo.

A sandy beach in the habitat mimics the sloped nesting sites of gharials in the wild. The water is temperature controlled, and heating coils under the beach help keep the gharials warm in cool weather.

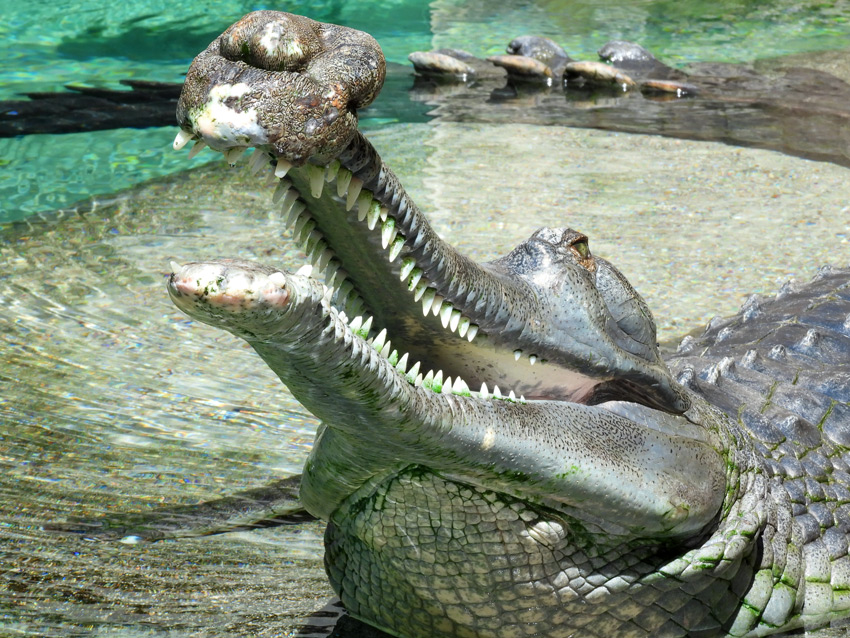

Feeding time for both the baby gharials and the adults is sometimes an adventure.

“The babies don’t quite take to frozen food items as easily,” Foster said, “so we do have to start them off on a variety of live fish items that mimic their natural hunting ability. They capture their own food.”

The adults, in contrast, are trained to line up at specific lanes when it’s time to eat, almost like a Sonic drive-thru. Cones are set up at the water’s edge and signal to the gharials which lane is theirs.

Photo by Teri Webster

“To start off with, we have to lure them with fish, showing them food to lead them over to the cones,” Foster said. “They start learning that, and they pick it up pretty quickly. It’s amazing.”

Gharials can see colors, and they understand where they are supposed to go, Foster added.

Once the cones are set up, the gharials politely park for their fish dinners, except for a female named Wally.

“Wally gets a little too excited, and she comes flying up out of the water trying to get to the food as quickly as possible,” Foster said. “She just knows that we have the food, and she’s coming to get it. She doesn’t want to sit patiently waiting for it.”

Female gharials are slightly smaller than males, ranging from about 12 to 15 feet and weighing about 350 to 400 pounds. Male gharials, in addition to being larger, have the distinction of a bulbous growth at the end of their snout, called a ghara. The growth allows males to vocalize, and it also helps them attract females.

Photo by Teri Webster

Whether male or female, gharials are an ancient species covered in tough scales, and they resemble a dragon or a dinosaur that walked from the pages of a book and into our world. With mythical resilience, ancestors of the gharials survived the extinction of dinosaurs and the Ice Age. Today, gharials face another formidable threat to their survival: people.

Habitat loss from the construction of dams and barrages, poaching, and accidental entanglement in fishing nets are among the reasons for the gharials’ dire status, experts say. Once found across more than 30,000 square miles of South Asian rivers, gharials now survive only in India and Nepal, National Geographic says.

Conservation projects at the Fort Worth Zoo and other organizations are working to ensure these magnificent creatures remain on the planet. In the future, the zoo hopes to get involved in a project that “reintroduces gharials into the wild,” said Erin Halvey, the zoo’s public relations manager. “In the meantime, maybe raising these young gharials will encourage additional facilities to house them, and they will be able to learn some of the breeding and rearing.”

Inside their habitat, the gharials are safe — swimming as fluid, living reminders of an ancient past and a hope that they will not slip into the silence of extinction.

Photo by Teri Webster

Photo by Teri Webster

Photo by Teri Webster