The little groups of women in the lobby of Theatre Arlington were spending their intermission comparing notes on the leading man in that afternoon’s matinee production.

“B.J. looks adorable in that suit!” said one. And another, “Has he ever played Elwood before?” The production in question was Harvey, Mary Chase’s 1944 comedy about an invisible six-foot rabbit and the human who could see him – Elwood P. Dowd, played at this performance by B. J. Cleveland, 46, the theater’s departing artistic director.

The show was a sell-out, the seats filled by age groups from young adults to seniors. But Cleveland’s admirers were dominated by the small army of grandmother-age groupies hanging on his every word. Maybe it was the artificial gray in his slicked-back hair or just the generous helpings of hammy charm he was dishing out. Or maybe his senior fans feel as though they’ve watched him grow up, literally – from local child stage star to host of a long-running kids’ TV show to resident artist at Casa Mañana to artistic director of Theatre Arlington.

The show was a sell-out, the seats filled by age groups from young adults to seniors. But Cleveland’s admirers were dominated by the small army of grandmother-age groupies hanging on his every word. Maybe it was the artificial gray in his slicked-back hair or just the generous helpings of hammy charm he was dishing out. Or maybe his senior fans feel as though they’ve watched him grow up, literally – from local child stage star to host of a long-running kids’ TV show to resident artist at Casa Mañana to artistic director of Theatre Arlington.

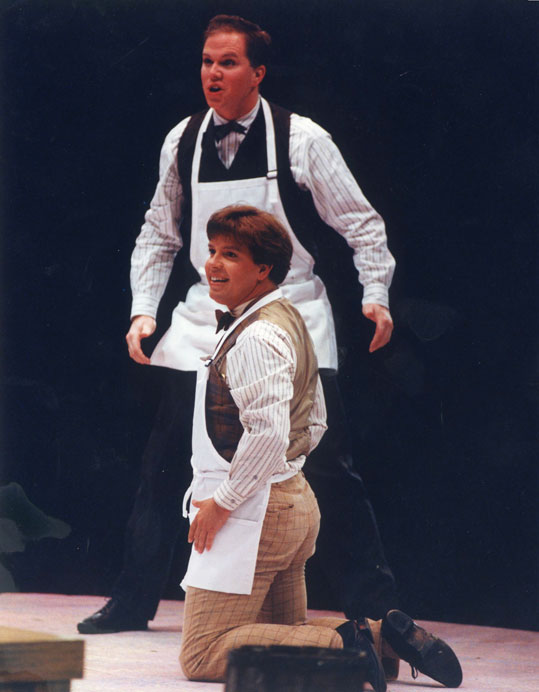

Though he has yet to turn 50, Cleveland has been acting, directing, moving scenery, running theaters – well, doing just about every job available in the Tarrant County theatrical world (except the business side) for 39 years. He got his Actors’ Equity card before he was old enough to drive. And except for the trace of a middle-age paunch, he exudes much of the same sly, youthful energy as when he appeared in his first Casa Mañana musical in 1970. By his rough estimation, he has acted in or directed 350 local, regional, and national shows since then.

But Cleveland is more than just an experienced theatrical hand. Professionally speaking, he’s the child of two seminal local stage entities, Casa Mañana and Fort Worth Theatre. Having witnessed – and in some cases, participated in – the creation and development of companies like Theatre Arlington, Hip Pocket Theatre, Stage West, Circle Theatre, and Onstage in Bedford during his relatively brief lifetime thus far, he jokingly refers to himself as “the old man historian.” He has been the face and soul of Theatre Arlington for more than 20 years, as artistic associate and, since 1994, as artistic director.

Boy wonder or historian, it’s time for him to move on. Cleveland himself suggested to the Theatre Arlington board that they get rid of his position. The board earlier this summer announced it would eliminate four of its eight staff positions in response to the continuing recession. But it was the news about Cleveland that shocked local theater fans.

Todd Hart has been Cleveland’s friend for 16 years; now he’s the man who’s assuming the role of Theatre Arlington’s executive producer in Cleveland’s wake and fielding the calls about his departure. “Some patrons have come to me and, to say the least, expressed their displeasure about B.J. ‘leaving,’ ” he said. “I tried to tell them that he’s coming back to do three shows next season.” Cleveland will act and direct on a show-by-show contract basis.

Still, a new chapter in Cleveland’s professional life has undeniably begun – one that in some ways has been delayed by his own local success. He plans to branch out into new styles of theater and explore the TV and film work that he skipped as a young man.

In the meantime, at the theater he led for so long, the show will go on without Cleveland’s name recognition and hands-on quality control.

Elizabeth Conly, a 26-year-old actor who co-starred with Cleveland in Harvey and who began theater studies with him when she was eight, credits him with inspiring her to pursue a stage degree at Baylor. “I won’t say the quality of productions will go down” after Cleveland exits as artistic director, she said, “but an important dynamic has changed forever. This will be a learning experience and an adventure – both for B.J. and for Theatre Arlington.”

At Harvey‘s curtain call, Cleveland got the expected standing ovation and explosive applause from the whole house, not just from the granny contingent. With a wide grin for which the adjective “puckish” was invented, Cleveland reached into his suit, pulled out a large handful of business cards, and flung them out into the audience. It’s an inside joke: While Elwood P. Dowd introduces himself with cards throughout the play, B.J. Cleveland needs no introduction to the Arlington fan base that has been like his extended family.

A Fort Worth native, he was christened Bobby Joe by his mother, who was 16, and his father, who was 18. With parents so young, Cleveland grew up more like their little brother than their child: There was a lot of pop music, dancing, movies, and TV in their home, but no connection to theater. When he entered second grade in 1969, Cleveland’s teachers noticed that he not only read at a fifth-grade level but could memorize long passages from books.

“They said, ‘You need to find a creative outlet for this child,’ and the Casa Mañana professional school for children was the only game in town,” he said. “It was an instant fit. By the time I was seven, I had played an urchin in my first professional musical [at Casa], Mr. Scrooge.”

Cleveland’s early teachers included Hip Pocket’s Johnny Simons and the late Bill Garber, co-founder of Fort Worth Theatre, as well as acclaimed, still-active Fort Worth actor-director-playwrights like Debra Jung and Linda Lee. Classes at Casa were held twice a week after school, and the teachers often required their child protégés to memorize and perform a scene a week. Students were expected to participate in all aspects of a production, including set building and painting. The program functioned more like a prep school than the high-falutin’ babysitting services that sometimes pass for youth theater classes today.

Sharon Benge is currently director of the drama department at Texas Women’s University. Among her many credits, she was founding director of Fort Worth’s Shakespeare in the Park and has directed shows across Texas and in Ireland, Scotland, and Czechoslovakia. Cleveland was a student in her youth classes at Casa Mañana in the 1970s.

“At one point we had almost 500 students at Casa, and it was necessary for someone to rise above the pack for me to notice them,” she said. Cleveland did that – but not physically. “It helped that he was short for his age, which is what you look for in child actors – the ability to play roles younger than they are and bring a maturity to them. He quickly became a mainstay around the theater.”

Cleveland counted as childhood friends and classmates Janine Turner (Northern Exposure) and The Facts of Life‘s Lisa Whelchel. They took field trips to New York City with Casa instructors to see Broadway shows that later became legendary, including A Chorus Line with the original cast.

By age 10, Cleveland was playing notable roles on the Casa main stage opposite visiting artists like 1940s MGM musical star and dramatic leading man Van Johnson. (“My grandparents thought I’d arrived,” he said.) He’d eventually work with Debbie Reynolds, Lainie Kazan, Kristin Chenoweth, and, of course, the grande dame of Casa Mañana, Ruta Lee.

Lee is famous for her sometimes bawdy behavior, but Cleveland wasn’t telling any backstage tales out of school. Asked if he had any anecdotes about the notoriously colorful Lee, Cleveland chuckled chivalrously, “Oh, I wouldn’t want to make ‘Auntie Ruta’ mad.”

But he did pass on one lesson he learned from Lee: “No matter how small your role is, you’ve got to work your ass off to make the audience love you.”

At age 12 he went on a year-long national tour of dinner theaters with the long-defunct Country Dinner Playhouse as the child lead in A Thousand Clowns. He remembers sitting around in dressing rooms after curtain and watching the adult actors laugh, drink wine, and pass joints over his head. (Even in the heat of the 1970s, some boundaries did prevail – he said he was never invited to partake of either the pot or the vino). Because of a “booking snafu,” he found himself with his own hotel room while they played Louisville, Ky., making himself sandwiches for lunch and watching TV all day long until he was escorted by his presumptive guardians to the theater. The grownup actors in A Thousand Clowns gently teased him for his very Texas-sounding name of “Bobby Joe,” and during the Colorado run they dubbed him “B.J.,” the professional moniker he’s used ever since.

“They gave me the name ‘B.J.’ right before I turned 13,” he said. “During the play, my character also turned 13. [The other actors] gave me a cake backstage. It felt like a growing-up experience. To this day, if someone has a birthday during a show, we bring out a cake.”

Upon his return, Cleveland enrolled in Boswell High School. His drama teacher there made a point of initially casting the very experienced young actor in smaller roles to avoid the appearance of favoritism. But he applied Auntie Ruta’s lesson even in those roles, to good effect.

In a Boswell staging of The Sound of Music, for instance, he played the butler. “I had already created a backstory [for that small role],” he said. “I figured that since the Von Trapp family was being chased by Nazis, there was a good chance there’d be a Nazi mole in the household. That was the butler. I played him with a scar on his face and a Boris Karloff accent.”

By the time Cleveland graduated from Boswell in 1981, he was working at Granbury Opera House and Casa Mañana as an actor and a youth theater instructor.

A major opportunity for national exposure came less than two years later, when producers from United Artists started casting a low-budget drama to be filmed at the recently opened Las Colinas film studios in Irving. The accountant for the film, the son of a woman Cleveland had performed with in Auntie Mame, nudged Cleveland to audition. Director Robert Altman eventually cast him in the film version of David Rabe’s scorching Vietnam-era drama Streamers. Although Cleveland’s character never speaks, he’s featured as the primary witness to the destructive back-and-forth among Matthew Modine, David Alan Grier, Mitchell Lichtenstein (son of pop art icon Roy Lichtenstein), and Michael Wright. His reaction shots, sprinkled throughout the movie, came about in an incidental, Altman-esque way.

“I had to lie on a bunk in my boxers all day [on set] with the sound of a rain machine over my head,” he said. “I fell asleep. Altman heard me snoring, quietly moved the camera over to my bunk, and then woke me up screaming, ‘This is my movie!’ Then he filmed me doing little bits of business on the bunk – waking up, looking around, hiding under the covers – that you see all through the movie.” When the movie was shown at the Venice Film Festival in 1983, the principal cast won an unprecedented ensemble award for Best Actor. Cleveland’s name wasn’t on the trophy, but his role had an impact.

By 1984, he was pursuing a theater degree at the University of Texas at Arlington and had joined the staff of Theatre Arlington as an administrative assistant and box office manager. The “assistant” position included everything from training volunteers to cleaning the toilets, but Cleveland was also tapped to act and direct as well as to develop youth outreach programs. Soon after, his former Casa Mañana buddy Lisa Whelchel invited him out to Los Angeles to audition for bit parts in her hit NBC comedy The Facts of Life. He earned a small recurring role in the 1984-’85 season as a hapless fraternity pledge.

When asked why his brief TV and feature film work didn’t encourage him to ditch Fort Worth for the show-biz shark tank, Cleveland reiterated a constant theme in his life: Tarrant County theater has always felt like a family to him, and the thought of leaving so many people who’d praised his work for so long was scary. In a weird way, it seemed ungrateful, too. The risk of taking the leap into the cold, hypercompetitive world of movies and television didn’t feel worth the potential reward, especially since he enjoyed so much professional security in his hometown.

When asked why his brief TV and feature film work didn’t encourage him to ditch Fort Worth for the show-biz shark tank, Cleveland reiterated a constant theme in his life: Tarrant County theater has always felt like a family to him, and the thought of leaving so many people who’d praised his work for so long was scary. In a weird way, it seemed ungrateful, too. The risk of taking the leap into the cold, hypercompetitive world of movies and television didn’t feel worth the potential reward, especially since he enjoyed so much professional security in his hometown.

“At the time, New York was a bigger temptation than L.A.,” he said. “But I just never got serious about the [film and television] industry. I was up to my chin in theater. Even as a child, I had an agent, but I was never sent out on many TV auditions.” When he became a young adult, the idea of auditioning for strangers to get work didn’t appeal much to him, since “I never lacked for stage work here because I kept getting jobs from people I’d worked with before. I guess the best answer is, ‘Shoulda, coulda, woulda …’ . “

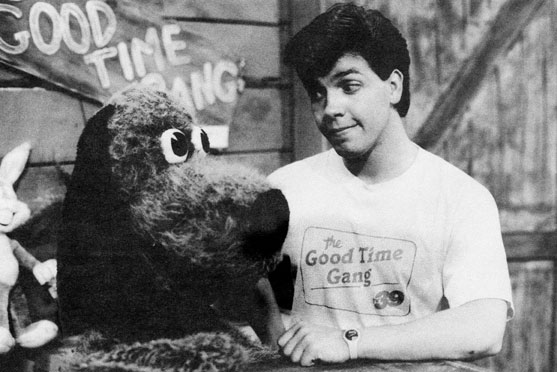

If the pursuit of national stardom wasn’t much on his mind, he only had to wait another two years for local and regional fame to come trotting after him. In 1986, when he was 23 and working as an artistic associate at Theatre Arlington, Cleveland got a call from a producer over at KXTX-TV Channel 39, then a local station owned by the ultra-conservative Christian Broadcasting Network, whose flagship show was the syndicated 700 Club with Pat Robertson. The producer had seen him in a show at Theatre Arlington. Would he be interested in auditioning for the role of an afternoon kids’ show host with a floppy-eared dog puppet sidekick? Yes, he would.

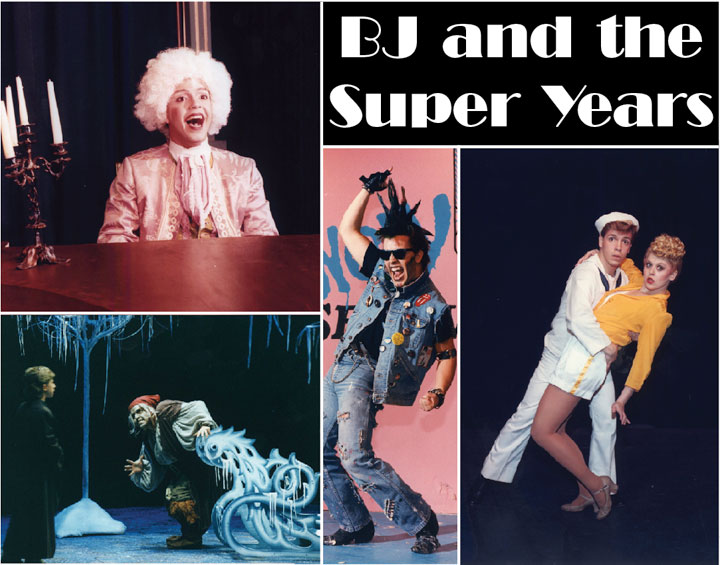

The Cartoon Clubhouse Starring BJ and Lester ran from 1986 to 1990. It was later refashioned as BJ and the Super Ones when it switched to the Disney-owned KTVT Channel 11, where it ran from 1990 to ’94. On his one day off each week from Theatre Arlington, Cleveland shot five half-hour segments with Lester, the puppet voiced and operated by producer Jack Glaze. They introduced cartoons, chatted with local guests on vaguely educational topics, and broadcast from locations around North Texas and, later, from Disney World. B.J. and Lester made regular mall and school appearances, served as grand marshals for area parades, and introduced Ice Capades shows at Dallas’ now-razed Reunion Arena.

Both TV shows were less memorable for their content than for the manic enthusiasm of Cleveland, whose persona was the epitome of the phrase “man-child” – it was nearly impossible to guess his age. In reality, the shows ran from when Cleveland was 23 until he was 31 – a period when many young men do a little hell-raising and a lot of socializing. But the standards of behavior expected from a kids’ show host could be harsh. He recalled one stranger who stopped by his table at a TGI Friday’s to ask him if he should really be having that margarita while there were children in the restaurant.

And then there was the issue of his sexual orientation. When The Cartoon Clubhouse started in 1986, anti-gay rhetoric nationwide was particularly nasty, with the likes of Pat Robertson – the most visible media symbol of the company he worked for – declaring that AIDS was God’s curse on gay men and that homosexuals should be quarantined.

Cleveland maintains that he never worried much about being fired because he was gay. The show was a ratings success, his bosses liked him, and of course he toed a very strict “don’t ask, don’t tell” line with the employers. The bottom line, he said, was that, “As long as I don’t officially ‘come out’ to the world, it won’t be an issue.” Still, the personal toll was real.

Cleveland maintains that he never worried much about being fired because he was gay. The show was a ratings success, his bosses liked him, and of course he toed a very strict “don’t ask, don’t tell” line with the employers. The bottom line, he said, was that, “As long as I don’t officially ‘come out’ to the world, it won’t be an issue.” Still, the personal toll was real.

“That was tough, working on a kids’ show [owned by right-wing Christian broadcasters] and not able to be honest about who I was,” he said. “I had a partner for a while, but we had to make sure he kept a separate condominium for appearance’s sake.” The strain of that arrangement eventually became too much, and the relationship ended.

Cleveland’s high profile in North Texas brought valuable publicity to Theatre Arlington, where he was acting and directing. The theater board hired him as artistic director in 1994, right about the time BJ and the Super Ones ended and his schedule opened up.

Since then, his name has been synonymous with that community theater. His brash but very detailed character performances in crowd-pleasing vehicles like Das Barbecü, Pump Boys and Dinettes, Little Shop of Horrors, Noises Off, and countless others helped keep the season subscriber base healthy. He became well known for his ability, as a director, to teach largely inexperienced actors to work at a new level of professionalism. A few years ago, both The Live Theatre League of Tarrant County and the Dallas-Fort Worth Theater Critics Forum honored him with lifetime achievement awards before he’d turned 45.

“B.J. always lets the actors know he has certain standards they’re expected to meet,” said Conly, his student and occasional co-star through the years. But rather than yelling or bullying, “he finds a way to approach people based on their personalities. It’s very intuitive.”

The theater also couldn’t have found a better personality or harder worker when it came to promotion. Cleveland’s presence expanded out from the theater into the general community through his roles as master of ceremonies for Arlington’s Fourth of July and Holiday Parade of Lights events.

Like most nonprofit arts organizations, however, Theatre Arlington has felt the sting of diminishing revenues as the recession has deepened over the last couple of years. Bigger, more expensive musicals were jettisoned in favor of small, character-driven comedies.

Cleveland said the economic crisis may have hurt Theatre Arlington worse than other arts groups because the theater’s executive director post had gone unfilled since 2001, when Penny Patrick left that job to become president of the theater’s board.

“All through the ’90s, Penny made sure there was a nest egg we could turn to for hard times,” he said. “But for the past eight years, we didn’t have anybody keeping the coffers filled. There was no single person in charge of fund raising. The board tried a management team approach, but it didn’t work.”

It didn’t help that Arlington is already ranked near the bottom of Texas cities for public arts funding in a state that, of course, ranks near the bottom of the national standings in that regard. And it’s a bitter pill for theater supporters that Arlington voters and leaders have ponied up millions of public dollars for the new Cowboys Stadium. “We are living in the shadow of that monolithic stadium,” Cleveland said grimly.

It didn’t help that Arlington is already ranked near the bottom of Texas cities for public arts funding in a state that, of course, ranks near the bottom of the national standings in that regard. And it’s a bitter pill for theater supporters that Arlington voters and leaders have ponied up millions of public dollars for the new Cowboys Stadium. “We are living in the shadow of that monolithic stadium,” Cleveland said grimly.

By spring of this year, deep staff cuts had become unavoidable. Cleveland met with several members of the board, one of whom asked him bluntly: How long do you plan to stay at Theatre Arlington? The question wasn’t intended as an insult. Fifteen years in the same artistic directorship is relatively rare among theater groups.

Cleveland himself began to look back, and he realized the pattern he’d fallen into: Year after year, he’d select the plays for a season, visualize it, figure out how to make it work within the budget, and then execute it. He was always working 18 months or so ahead of the calendar. “Then one day you look around, and a dozen years have gone by,” he said.

“I’ve always felt I became an artistic director too young,” he said. “Most people get that title in their 50s or 60s.”

Ultimately Cleveland suggested that, to save money, the board should retain him on a contract basis rather than as a staffer. His salary was small to begin with, and the modest health insurance he received was through his membership in the Actors’ Equity union, not as a theater employee. Offering his job as a sacrifice to the budget ax wasn’t easy, but Cleveland had neither the inclination nor the background to add fund raising to his duties, and that’s what the theater badly needed. Besides, he was itching to do other things with his career.

The artistic director position was dissolved, and Todd Hart, B.J.’s longtime friend, was lured away from his job as a Casa Mañana associate producer to fill the new executive producer role. Hart has 30-plus years of experience directing and performing at Casa as well as Theatre Arlington, Circle Theatre, Dallas Theater Center, and many other companies. “Todd is a great combination of artistic ability and business acumen,” Cleveland said. “I never had any interest in running the business side of things.”

Hart’s position as executive producer means he’ll oversee grant-writing and the pursuit of revenue from sources other than single-ticket and season subscriber sales. “I’m kind of unusual [in the arts world], in that I enjoy using my left brain and my right brain,” he said with a chuckle. “I actually like sitting down to process a stack of paperwork.”

After the recent final performance of Harvey, Cleveland stood sheepishly onstage amid the applause of fans and friends as Arlington Mayor Pro Tem Lana Wolff presented him with a plaque declaring Aug. 30 to be “B.J. Cleveland Day.” He was enormously gratified and a little disturbed by the gesture, which carried a faint funereal scent.

“I’m afraid Harvey was advertised as ‘the final viewing of B.J. Cleveland,’ ” he said later.

While the “artistic director” sign has been removed from his office at Theatre Arlington, he’s hardly disappeared from the premises. He’s directing the upcoming first show of their 2009-2010 season, the Mark Twain musical Big River, as a contract artist.

“B.J. has been talking about moving on for five or six years now,” Hart said. “But he was always a little worried, saying things like, ‘Do you think anyone would want to hire me?’ And I always said, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ “

“B.J. has been talking about moving on for five or six years now,” Hart said. “But he was always a little worried, saying things like, ‘Do you think anyone would want to hire me?’ And I always said, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ “

Indeed, within hours of the announcement, offers of work began pouring in via phone and Facebook. Cleveland’s plate is full for the next two years. He continues to work as an adjunct professor at UTA. The Creative Arts Academy in Coppell, which offers youth acting classes for stage and screen, has hired Cleveland as its artistic director. He’s already been cast in this fall’s regional premiere of The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee at Theatre Three in Dallas. Uptown Players, a Dallas company that specializes in outrageous, often gay-themed works, has tapped him as director for next year’s Broadway Our Way revue.

Jeff Rane, executive producer for Uptown Players, has known B.J. for many years and performed in numerous Theatre Arlington shows that he directed. Cleveland was asked to star in Uptown’s premiere production When Pigs Fly back in 2002, and last fall’s hit Legends! was selected in part so the prodigy of Cowtown family theater could appear as a drunken, foul-mouthed, past-her-prime Hollywood star – in full, Judy Garland-inspired drag, no less.

“Our manifesto is different from the family-friendly works that Theatre Arlington is known for,” Rane said. “We lean toward edgier shows for an adult audience. Now that B.J.’s schedule has opened up, we’re looking forward to more collaborations with him as an actor and a director.”

“For years people have known me as the musical comedy person, the guy who’s trying very hard to make you laugh,” said Cleveland. But now, he said, “I can do things that challenge and frighten me. … I don’t have to worry about the survival of an entire theater while I’m on stage. I can put on a pair of glasses and a business suit and deliver serious lines in a contemporary drama at Circle or Stage West.”

Most significantly, Cleveland is returning to that “shoulda-coulda-woulda” moment 25 years ago when he took small but visible roles in a Robert Altman film and a hot network TV sitcom. This time he wants to do things differently. He’s been accepted as a client at Dallas’ Mary Collins Agency and has been sent out on auditions for several national TV commercials.

At 46, Cleveland has no qualms about playing the goofy middle-age office worker in, say, a breakfast cereal commercial. In fact, it feels just right. His dream is to graduate into character roles in sitcoms and national tours of blockbuster plays and musicals, like the one (Peter Pan with Cathy Rigby) he turned down years ago while working at Theatre Arlington. In truth, he’s barely entered his prime as a Nathan Lane/Leslie Jordan type – a rubber-faced comic supporting player on stage and screen. If that description was the epitaph carved on his gravestone, he’d be happy.

“The idea of making a living touring America as Belle’s father in Beauty and the Beast sounds great to me,” he said. “Until then, if I have to, I’ll be the 12th spear-carrier in Julius Caesar who helps build the set during the day. If you don’t have that attitude in the theater, you’re not going to get anywhere.”