That’s when the federal government has told the television industry to stop transmitting the old-style analog signals and switch entirely to digital signals. So if you own an analog tv set and don’t subscribe to either cable or satellite — thus receiving only over-the-air signals — your old set is going to go dark that day.

That’s when the federal government has told the television industry to stop transmitting the old-style analog signals and switch entirely to digital signals. So if you own an analog tv set and don’t subscribe to either cable or satellite — thus receiving only over-the-air signals — your old set is going to go dark that day.

Years in the making, this decision to go digital has far-reaching ramifications, and not just for your ability to watch your daily programs. Billions of dollars are at stake — including an expected government windfall of at least $10 billion, to come from auctioning off the excess broadcast spectrum that will be freed by the move to digital. A power struggle is also going on over who will control what you see, with those who provide program content — such as local broadcasters and networks — on one side and those who are the conduits for the shows — cable and telephone companies — on the other. Depending on who wins some epic regulatory battles, you may have a rich new menu of programs to watch, including reports on election campaigns and local high school football, and some media giants may earn bundles of extra money. Everyone from local newscasters to actors, writers, and producers of tv programs also has an enormous stake in how this transition turns out.

At least as important is the parallel battle going on to determine whether the public interest will be any better protected in this brave new digital world than it is now — that is, whether tv stations will have to provide more coverage of local and federal elections, for instance, as well as giving airtime to nonprofit groups.

But, back to what’s probably the top concern for those of you stuck in the analog age. Rest assured (sort of): Congress has allocated up to $1.5 billion to help consumers buy equipment that will let old tv sets connect to the new video stream — an amount that some think is as inadequate as the money set aside to educate the public about what is happening. But you, at least, have gotten the word. Just be sure to get in line before they run out of vouchers.

Americans — and just about everyone else in the world — in the post-millennial era have become accustomed to the fast pace of technological change. Hello, cassette tape, goodbye 8-track — oh wait, let’s get a c.d. player — no, an iPod. Your computer is five years old? Ancient! That cell phone in your pocket only accepts e-mail and doesn’t take pictures? You’re still watching movies on the VCR, not the DVD? You’re, like, so analog, dog.

There’s a major difference between all those technological changes and this one, however: This one is mandated by the government, to be final on a certain date. After that, analog tv sets that aren’t connected somehow to the digital spectrum might as well be turned into planters or, perhaps, aquaria. And no more analog sets will be made after March 1, 2007.

The government didn’t start the digital tv revolution, of course. That happened in 1981, when a Japanese broadcasting company demonstrated a high-definition tv system to an engineering trade group meeting in San Francisco. The picture quality — though non-digital — was stunning because it had more lines — 1,125 — on the screen than the standard 525 lines that analog sets could receive.

Americans hated the thought that the Japanese might beat them to HDTV. Around this time the Japanese were buying a lot of U.S. real estate, and, as one source said, “there was a taste of xenophobia in the air in Washington at the time.” So American companies formed what they called a Grand Alliance and went one step further than the Japanese, inventing digital high-definition tv. For HDTV to work here, broadcasters had to digitize their signals, because otherwise there wasn’t enough room on the part of the spectrum allocated to broadcasters by the government.

Digital broadcasting may change the landscape even more than the advent of color tv did. The amazingly sharp pictures are the first difference that consumers see with digital. It also produces better sound and doesn’t have ghosts.

But a digital signal — because it is compressed into binary code — also takes up much less space on the broadcast spectrum than analog signals. That difference has a major impact on how much information can get delivered to your tv, as opposed to how sharp the delivery is. In the same frequency range allotted to a single traditional tv station to deliver one signal, for instance, a digital provider can deliver six streams of programming. In fact, that’s one of the big questions to be answered in the digital revolution: When a cable company agrees to carry the signal of a local tv station or network, who gets to decide how to allocate the other five channels’ worth of programming that can now be beamed to viewers in the same spectrum “space” that the station’s one analog signal took up? If you think the answer carries big-buck implications, you’d be right. And if there’s money to be made, it’s not surprising that there’s also a fight over who gets to make it.

The looming digital tv switch has inspired the latest battle in a long-running war between broadcasters and cable companies — one legal facet of the continuing metamorphosis of American tv from a world dominated by three networks, all of which aired their programming over the airwaves, free to consumers, to today’s constantly changing airscape of networks, independent stations, and cable channels. It’s a universe that teens revel in and many adults shake their heads at, with a constant shifting of what were once rather simple rules. Phones, computers, tvs, and radios used to be separate appliances that knew their places, with service provided by separate companies. Now you can buy phone service from your credit card company, check your frequent-flier miles via cell phone, play satellite radio through your computer, buy internet service, phone service, and tv access from a single company — and maybe one day soon, order up your children and clean your teeth on your Blackberry.

The looming digital tv switch has inspired the latest battle in a long-running war between broadcasters and cable companies — one legal facet of the continuing metamorphosis of American tv from a world dominated by three networks, all of which aired their programming over the airwaves, free to consumers, to today’s constantly changing airscape of networks, independent stations, and cable channels. It’s a universe that teens revel in and many adults shake their heads at, with a constant shifting of what were once rather simple rules. Phones, computers, tvs, and radios used to be separate appliances that knew their places, with service provided by separate companies. Now you can buy phone service from your credit card company, check your frequent-flier miles via cell phone, play satellite radio through your computer, buy internet service, phone service, and tv access from a single company — and maybe one day soon, order up your children and clean your teeth on your Blackberry.

Congress passed a law in 1992 requiring cable companies to carry local stations’ programming as well as that of cable channels like CNN and ESPN. The cable industry challenged the law, saying it violated their freedom of speech — that Congress could no more require them to carry a particular channel than it could require a newspaper to print a columnist’s viewpoints over the objections of the publisher. The Supreme Court upheld the law in 1997, ruling that Congress intended its “must-carry” regulations to preserve the benefits of free over-the-air broadcasting and provide fair competition.

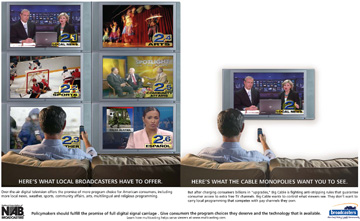

Now, however, the technology that helps broadcasters transmit more than one program at a time digitally — called multicasting — has reopened the battle. Broadcasters see the digital changeover as a chance to transmit not only their basic programming, but also additional channels providing purely local news or religious broadcasting or high school sports or whatever, all carried on cable. There’s little point in producing more programs, they say, if there is no guarantee viewers will be able to see them.

Now, however, the technology that helps broadcasters transmit more than one program at a time digitally — called multicasting — has reopened the battle. Broadcasters see the digital changeover as a chance to transmit not only their basic programming, but also additional channels providing purely local news or religious broadcasting or high school sports or whatever, all carried on cable. There’s little point in producing more programs, they say, if there is no guarantee viewers will be able to see them.

The cable companies, in turn, maintain that they need only carry the broadcaster’s primary signal, as they have been required to do for analog. It’s a matter of who’s going to make the big bucks off digital — broadcasters who want the option of more programs on which to sell more ads or cable companies like Comcast or Time Warner, which can sell their services to more subscribers who want more channels.

Multicasting offers the chance for more and better programming, especially local programming, said Dennis Wharton, spokesman for the National Association of Broadcasters, the industry trade group. His organization thinks its way will ultimately prevail. “If stations are going to invest a lot of money in high-quality programming, are they going to do it when 65 percent of their audience might not have a chance to see it?” he asked.

The Federal Communications Commission is right in the middle of the fight over these rules. FCC Chairman Kevin Martin, a Republican, favors the multicasting requirement but has said he’s not sure he has the votes on the commission to pass it.

So if broadcasters don’t win these rules from the FCC, which regulates broadcasting and cable, what’s their worst-case scenario? “If broadcasters are not granted multicast carriage rights, millions of consumers will be denied access to a host of free programs that would compete directly with pay cable networks,” Wharton said. “Gatekeeper cable operators are spending millions to lobby against this pro-consumer rule, because giant cable networks hate the idea of additional competition from program providers that they don’t control.”

Some reports say that the broadcasters have spent $30 million to try to win this fight. “If that’s what we’ve spent to give consumers quality programming, we’ll plead guilty to that,” Wharton said. The National Cable and Telecommunications Association, cable’s trade group, has been lobbying just as vigorously.

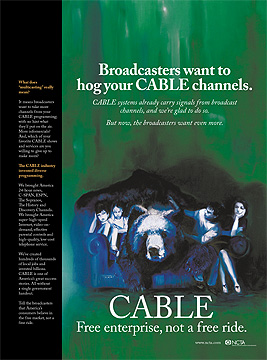

Competing ads claim, on the one hand, that “broadcasters want to hog your cable channels,” maybe for infomercials that would crowd out popular cable shows, and, on the other, that local broadcasters can offer channels with news, sports, arts, community affairs, weather, and Spanish-language programming, unless “Big Cable” is allowed to “control what viewers see” while charging billions for upgrades.

Rob Stoddard, the cable group’s spokesman, argues that the broadcasters’ ad is nonsensical. “Look, cable companies don’t get any customers if they don’t carry what the local stations are offering,” he said. “It would be insane and suicidal in a competitive sense not to carry these broadcasts.”

But NCTA rejects multicasting. For one thing, in a big city, “you might have 10 to 12 over-the-air stations. So you could have 60 streams” of programming. That can crowd out space for other programs that the public might prefer, Stoddard said.

Oh, and don’t forget the phone companies, also players in this complex drama.

In June, Verizon, the Association for Public Television Stations, and PBS announced that Verizon’s fiber-optic FiOS tv service will carry the full digital signal of up to three public tv stations in their service areas, including North Texas. The transmissions are 100 percent digital, and, depending on the plan a person buys, can contain as many as 26 high-definition channels and access to on-demand movies. AT&T has just launched its new television service, U-verse, in San Antonio.

Moving into video “is our opportunity to sink or swim,” said Bill Kula, a Verizon spokesman in Irving, because the company has been losing phone revenue to internet providers and because some people are dropping their land lines and using cellular phones exclusively. Providing home tv service stems “as much from our survival as it does from developing gee-whiz technology.”

Moving into video “is our opportunity to sink or swim,” said Bill Kula, a Verizon spokesman in Irving, because the company has been losing phone revenue to internet providers and because some people are dropping their land lines and using cellular phones exclusively. Providing home tv service stems “as much from our survival as it does from developing gee-whiz technology.”

These moves have pitted the cable giants such as Time Warner and Comcast against the phone companies in the fight over customers and regulatory issues. Cable is regulated locally, and phone companies are working in Congress and the state legislatures to avoid these city-by-city franchising rules. People like local U. S. Rep. Joe Barton have gotten into the fray, sponsoring, in Barton’s case, a bill allowing phone companies to obtain tv franchises from the FCC rather than negotiating them city by city.

In Texas, a state law passed last year allows AT&T and Verizon to sell their television services without having to negotiate franchises locally. The Texas Cable & Telecommunications Association has sued in both federal and state courts, charging that the law is unconstitutional because it discriminates against cable companies that are locked into existing local franchises. Kirsten Voinis, TCTA spokesperson, said that the legislation could allow phone companies to serve only the areas of a community that they want to serve, unlike cable companies that must “build out” service to entire communities, including low-income and therefore less profitable areas.

It’s like standing on the edge of the Black Hills right before the battle of the Little Big Horn — gold and prospectors on one side, the Sioux on the other, and the U.S. Cavalry in the middle. The profit motives are so strong, and the territory so new, that the only thing for sure about the outcome is that it’s likely to be bloody and that there will be plenty of innocent victims.

Digital tv is already here or within reach for most American tv viewers. The problem is figuring out how to help those who can’t make the transition so easily.

Digital tv is already here or within reach for most American tv viewers. The problem is figuring out how to help those who can’t make the transition so easily.

Most of the country’s 1,750 local broadcast stations and all the major networks already transmit some of their programs digitally. For example, North Texas’ public television station, KERA, sends out digital as well as analog signals for every one of its programs. Then there’s digital cable, which allows customers to receive more channels.

Some local stations as well as cable channels also provide high-definition tv (HDTV) programs. Again as an example, KERA offers Nova in high-definition format. Cable channels such as ESPN, HBO, Showtime, and Starz, among others, also offer HDTV. Keep in mind that high-definition tv, though it was the advance that started the revolution, is just one of the things you can get from digital tv technology, if you have the right set. So far, HDTV sets are at the high end of the price ladder, but the cost falls every year. They have pictures that stop you in your tracks as you troll the aisles of Best Buy or Circuit City —you feel you can see the fuzz on the tennis balls, see every missed whisker on some hunk’s famous face.

Most of the 110 million tv-equipped houses in this country are either cable or satellite service subscribers, meaning they already get or will have no problem getting digital service. But between 21 and 45 million households — estimates vary that widely — have sets that receive only analog signals. Along with the February 2009 deadline for going digital, Congress established a fund to provide vouchers for people to buy set-top boxes, which consumer experts now guess will cost $60 or more, to convert those analog signals so the old sets will continue to receive a picture when the switch gets flipped.

Congress authorized an initial $990 million to send two $40 coupons for the converter boxes to each household requesting them. After subtracting administrative costs, that comes out to more than 22 million vouchers — and Congress made provisions for increasing the fund to $1.5 billion. That’s simply not enough, said Consumers Union senior policy analyst Jeannine Kenney; her organization contends that consumers will have to spend about $3.5 billion for the converters.

The Commerce Department agency that is administering the program has requested comments from the public by Sept. 25 about how it should set up the voucher program. The agency has acknowledged that the boxes, which are not commercially available yet on any widespread basis, may cost more than $40.

Furthermore, the agency has said that the act was intended to help only the estimated 15 to 19 percent of U.S. households that currently rely exclusively on over-the-air transmission. So if you have cable or satellite for any tv set but also have other unconnected analog sets, say in the kitchen or workshop, too bad. They will receive no converter box — and therefore no picture — after the 2009 deadline.

Furthermore, the agency has said that the act was intended to help only the estimated 15 to 19 percent of U.S. households that currently rely exclusively on over-the-air transmission. So if you have cable or satellite for any tv set but also have other unconnected analog sets, say in the kitchen or workshop, too bad. They will receive no converter box — and therefore no picture — after the 2009 deadline.

The National Association of Broadcasters takes strong exception to that proposal. “We would hope that no broadcast-only tv sets are forced to go dark during this transition,” said Wharton, the NAB spokesman. He estimated that there are some 28 million “broadcast-only” — that is, analog — sets in households that also subscribe to cable or satellite.

Another potential problem during the transition to digital, according to Kenney, is that Congress set aside only $5 million for consumer education about the changeover — insufficient, she said. Consumers Union is concerned that many of the analog sets are owned by elderly and low-income people who won’t be reached by the explanations — or the vouchers.

“This is a government-mandated transition in technology,” Kenney said. “Consumers are used to market-driven transitions. So if the government is going to force this transition, then it should compensate consumers who may not be ready to buy new sets.”

If the digital revolution looks likely to leave some folks in the dark because of the price of new sets or cable or satellite service, it’s going to be even more costly for broadcast companies to convert their operations.

Belo Corp., for instance, which owns 19 television stations, including WFAA/Channel 8 in Dallas, has spent $85 million in recent years to convert its towers and other transmitting equipment, said vice chairman Jack Sander. The average station, he said, is continually replacing old analog equipment with digital, which he estimated would cost from $3 million to $5 million per station.

The NAB’s Wharton said that price tag could be as high as $10 million, if a station is planning to produce its own high-definition programs and advertising.

The problem, both men said, comes in guessing whether or not those expenses will be justified by the additional streams of programming (and therefore advertising) that the broadcast companies are hoping for, but that the cable companies are resisting. There’s “no guarantee that a dime of that expense” will come back if viewers can see only one stream of digital broadcasting on their local cable system, Wharton added.

Paying for the conversion is even tougher for traditionally cash-strapped public television stations, even with substantial federal help. KERA executive vice president Kevin E. Martin (no relation to FCC Chairman Kevin Martin) put a $10 million price tag on his North Texas station’s move to digital — for installing a new digital antenna, transmitter, and microwave as well as purchasing production equipment such as high-definition cameras, switchers, and routers plus a digital server to archive huge files that previously were stored in an extensive tape library.

The cable industry has agreed that its operators will carry as many as four streams of those nonprofit stations’ programs. Cable companies wanted to “provide protection for public broadcasting because it appeared as if they were going to get left out of the digital transition,” said NCTA spokesman Stoddard. Public television’s “great programming such as children’s shows and documentaries” are in line with cable’s intent to offer quality shows to subscribers, he added. “So it was altruistic” mixed with a desire to show the marketplace as a better regulator of what cable should carry, he added.

Sander, who is on the NAB board, argues that if local commercial stations do not get the opportunity to present more than one stream of programming — in other words, if multicasting must-carry rules aren’t in effect — then the marketplace will be denied the variety that is possible. “You can’t build a business plan on 20 percent of a market. It seems to me that if you want expanded local information, then multicasting is the only option,” he said. Otherwise, people will go to the internet for it.

Sander, who is on the NAB board, argues that if local commercial stations do not get the opportunity to present more than one stream of programming — in other words, if multicasting must-carry rules aren’t in effect — then the marketplace will be denied the variety that is possible. “You can’t build a business plan on 20 percent of a market. It seems to me that if you want expanded local information, then multicasting is the only option,” he said. Otherwise, people will go to the internet for it.

Sander said he thinks local broadcasters have been doing a good job on the technical side of the transition, but that consumers are still very confused (not to mention the people who sell tvs). Broadcasters have a responsibility to let the public know what’s happening, he said, and the “best people to do that are television stations.”

Both cable and broadcasters claim to want only what’s best for the public, of course. But a major part of the digital discussion isn’t about who will carry how many streams of programming. It’s about how all the providers — broadcasters, cable, satellite, and phone companies — will have to meet tv’s traditional public-service obligations in the digital era.

FCC Commissioner Michael Copps, a Democrat, says that while the mechanical aspects of the digital transition are being addressed, both the industry and the FCC seem to be “ignoring the big question — what should the public interest obligations be?”

That question has prompted public- interest advocacy groups to wade into the digital tv fray, and it could have a major effect on what you see on all those new digital channels.

Broadcasters, unlike print media, are licensed by the government. And as a condition of getting and keeping their licenses, local stations are required by law to serve “the public interest, convenience, and necessity.” That has been more and less stringently defined over the years, but the principle has been strong enough to allow parents to band together to lobby for improvements in children’s television programming and anti-smoking advocates to start the ball rolling toward the end of cigarette advertising on tv.

In one of the most significant cases, the Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ used the public-interest requirements to overturn the license renewal of a Jackson, Miss., television station. In the 1950s and 1960s, that station repeatedly refused to give airtime to black leaders who sought to rebut its coverage — or lack of coverage — of their civil rights and political concerns; the station later became majority black-owned. The church group also successfully petitioned the FCC to issue equal employment opportunity rules for the broadcast industry.

Copps contends that there is a “rich opportunity for both communities and broadcasters” with digital tv, assuming that the FCC gets its policies right. But “if we get these policies wrong,” then there will be infomercials masquerading as real programming, he added.

Others, however, worry that digital’s ability to carry so many more programs will undercut one of the main legal bases for the public-interest requirements — the idea that the scarcity of broadcasting frequencies gives the government the rationale for laying down limits on tv’s constitutional free speech rights. Copps believes, however, that “the spectrum rationale is still there” for such requirements.

Others, however, worry that digital’s ability to carry so many more programs will undercut one of the main legal bases for the public-interest requirements — the idea that the scarcity of broadcasting frequencies gives the government the rationale for laying down limits on tv’s constitutional free speech rights. Copps believes, however, that “the spectrum rationale is still there” for such requirements.

Public-interest groups have been urging the FCC for more than a decade to make clear what broadcasters’ obligations will be in the digital era. In 1995 the Media Access Project, a public interest advocacy law firm in Washington acting with a number of other organizations, urged that broadcasters, with so much more programming time available, be required to provide free time for candidates for federal and local political offices, educational programs for children, and public access to digital broadcasting for nonprofit groups that could provide community-based programs. When the commission allotted extra spectrum to broadcasters for the digital transition, it promised to return later to these requests.

In December 1999, the FCC issued what it calls a “notice of inquiry” about broadcasters’ public-interest obligations in the digital age. “This proceeding is long overdue,” said then-commissioner Gloria Tristani, a Democrat. “The public-interest standard — the bedrock obligation of those who broadcast over the public airwaves — has fallen into an unfortunate state of disrepair over the years. It’s time to put up scaffolding and get the restoration under way.”

Defining “the public interest” has never been easy. Fellow commissioner Michael K. Powell, a Republican, concurred in launching the inquiry but thought the effort was premature for “a service that has yet to blossom.” He was, he said, reminded of the efforts by designers to make the Empire State Building a world-class structure. They wanted a mast on the building for mooring dirigibles carrying passengers visiting the city. Mass transit by dirigible never happened, and Powell thought that someday the proposals on public interest for digital tv might suffer the same fate as the dirigible mast.

Powell became FCC chairman two days after President George W. Bush was sworn in, and the public-interest inquiry went the way of the proposed dirigible mast—except for requirements for children’s programming. Nor has the commission returned to the question under chairman Martin.

In 2004, a coalition of nine groups proposed to the FCC how the public interest might be served by broadcasters. These groups suggested that broadcasters must air a minimum of three hours a week of local civic or electoral affairs programming on their primary digital channels between 7 a.m. and 11:35 p.m., that is, when most people would be watching. During the six weeks before a general election, at least two of those three hours would have to run from 5 p.m. to 11:35 p.m. Stations would also have to report quarterly, on their web sites and in their public files and in more detail than currently required, on the programming they feel meets this guideline. This Public Interest, Public Airwaves Coalition includes such organizations as the Benton Foundation (whose president is now Gloria Tristani), the Center for Digital Democracy, Common Cause, the Media Access Project, and the Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ.

The people who create the programs you see — writers, directors, and performers — have a clear stake in the digital era, said Jonathan Rintels, president of the Center for Creative Voices in Media, another coalition member. “Right now it looks like big media fighting big media,” he said. “Will it be a few media conglomerates — many voices and only a few ventriloquists — or will it be an explosion, as we hope, of more opportunities” for better and more varied programming? “The jury is out on that—and it’s where our work is focused.” Without a public-interest obligation, Rintels added, “there is nothing preventing a broadcaster from running five shopping channels.”

The people who create the programs you see — writers, directors, and performers — have a clear stake in the digital era, said Jonathan Rintels, president of the Center for Creative Voices in Media, another coalition member. “Right now it looks like big media fighting big media,” he said. “Will it be a few media conglomerates — many voices and only a few ventriloquists — or will it be an explosion, as we hope, of more opportunities” for better and more varied programming? “The jury is out on that—and it’s where our work is focused.” Without a public-interest obligation, Rintels added, “there is nothing preventing a broadcaster from running five shopping channels.”

If the 2009 deadline for an end to analog broadcasting holds up, broadcasters at that point will return to the government the extra share of the airwaves that they were given for the transition. In the months before the deadline, the government will start auctioning that spectrum, minus some reserved for public-safety use. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that this auction could yield $10 billion, some of which will subsidize the converter vouchers. Congress is counting on applying much more of the billions toward reducing the federal deficit.

Companies that bought the newly available space on the spectrum action could use it for purposes that would be almost as important as the rest of the digital revolution.

They’d be likely, for instance, to dramatically expand mobile broadband wireless service, which could especially benefit first responders such as fire departments. Public-safety communications proved especially vulnerable during the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina last year.

Delivery of high-quality video and audio programming to cell phones could take up another part of the spectrum. And rural high-speed wireless service could be improved because towers transmitting in the frequency range that would be freed up could cover more territory than the frequencies being used now.

For someone whose earliest memory of television was watching test patterns on the set before Howdy Doody came on the air, it’s a stunning new world. The pictures and sounds we receive in our homes bear little resemblance to those early fluttery images, and 10 years from now, who knows what new options we’ll have? Content is an entirely different question. Whether all this new space on the airwaves will be filled with more infomercials, reruns, shopping channels, and marginal programming or will be used in part to help Americans become better educated about politics and their society — that remains anybody’s guess.

Kay Mills, a former Los Angeles Times editorial writer, has written about the FCC for the Newhouse newspapers and the Times. She is the author of Changing Channels: The Civil Rights Case That Transformed Television, about the landmark Mississippi communications law case.