Green bandanas and leather jackets emblazoned with “Boozefighters” pegged a group of men and women as members of a motorcycle club, and they were living up to their name at the White Elephant Saloon a couple of Sundays ago while singer-songwriter Jordan Mycoskie was on stage. Wanting to hear a Johnny Cash tune, they requested it with persistence — in fact, they demanded it.

“I Walk The Line!” a guy hollered over and over, interspersing his commands with random profanities. The others half-heartedly chanted “I Walk The Line” to humor their buddy. Mycoskie, who wrote and recorded “I Don’t Do Covers,” has played hundreds of raucous gigs, and he wasn’t intimidated. Like many honkytonk entertainers, he doesn’t jump to orders bellowed by fools. He put down his acoustic guitar, fetched his electric Stratocaster, and steered his band into the reggae classic “No Woman, No Cry” — a song not even close to the Man in Black. One of the bikers walked up to the stage and tried to sing along even though he didn’t know the words, while a biker chick snuck up behind him, linked her arms around his waist, and started dry-humping him like a Chihuahua after a Spanish fly speedball.

“I Walk The Line!” a guy hollered over and over, interspersing his commands with random profanities. The others half-heartedly chanted “I Walk The Line” to humor their buddy. Mycoskie, who wrote and recorded “I Don’t Do Covers,” has played hundreds of raucous gigs, and he wasn’t intimidated. Like many honkytonk entertainers, he doesn’t jump to orders bellowed by fools. He put down his acoustic guitar, fetched his electric Stratocaster, and steered his band into the reggae classic “No Woman, No Cry” — a song not even close to the Man in Black. One of the bikers walked up to the stage and tried to sing along even though he didn’t know the words, while a biker chick snuck up behind him, linked her arms around his waist, and started dry-humping him like a Chihuahua after a Spanish fly speedball.

Talk about your honkytonk yin and yang: Through an adjoining doorway and up a staircase from the bikers, a completely different performance was unfolding, as part of the Clubhouse Concert Series held each Sunday night. At the private venue called Upstairs at the White Elephant, singer-songwriters Adam Hood and Sunny Sweeney performed in front of 75 patrons who sat in folding chairs and listened to each song, each word, with a hushed reverence. The two-hour performance was digitally recorded and within days would be edited and available for worldwide viewing free of charge at www.Hi-IQmusic.com. The crowd clapped enthusiastically and lined up afterward to shake hands, buy CDs, get autographs, and snap photos with the artists.

Beaming about it all was Joni Beard, a soccer mom turned concert promoter with a soft spot for struggling artists. She’s provided them a showcase for five years, although keeping the venue alive hasn’t been a breeze. Generating enough money to rent a public address system, wrangle hotel rooms, and pay musicians is a weekly challenge, made even more difficult after the recent loss of a sponsor. Beard’s brainchild sprang from the occasional performances she began organizing in a small clubhouse at a Westside apartment complex in 2002. The shows were patterned after intimate house concerts, with small cover charges that went to the performers. And rowdies weren’t welcomed. Beard’s rule — more like a mantra, really — is posted clearly at shows: “Sit down. Shut Up. Listen.”

Alcohol is ever-present but not typically consumed in massive quantities. Smokers have to go outside to get their fixes. The listening room atmosphere makes artists eager to play, even for short pay. Budding stars such as Randy Rogers and Stoney LaRue honed their performances and developed a North Texas following at Beard’s shows, and they’ve maintained a strong fondness for her even after moving on to bigger and better stages. “Coming down to Fort Worth, I started at those Clubhouse Concerts,” said LaRue, who was based in Oklahoma and just beginning his career in 2002 when Beard recruited him. Now he’s big-time, having been named 2007 Artist of the Year at the Gruene With Envy Awards Ceremony in Austin. “It’s pretty amazing how the Clubhouse went from a room with 10 people to what it is now,” he said. “It never was about money. As long as the audience was listening, it was worth going.”

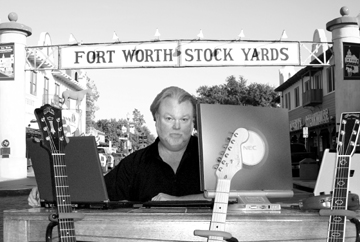

Meanwhile, Dallas techno-dude Steve Borchert and his video recording equipment have become fixtures at the Clubhouse. He’s teamed up with veteran Stockyards entertainer Brad Hines to promote a web site aimed at spotlighting Stockyards artists while spreading the gospel of Texas Music. Already, the site is getting hits from the Netherlands, Italy, France, Spain, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and all over the United Kingdom as well as the United States. “We’re not YouTube,” Hines said. “We want to be a musical performance archive that is unique and special.” The splashiest news at the Stockyards this year was the high-profile bomb known as West Exchange, or West-Ex, a half-dozen new bars that opened collectively last summer and quickly went belly up. Spencer Taylor earned his fame in the 1980s for establishing Billy Bob’s Texas and Dallas Alley, but that was then and this was … wow, a disaster. Spencer tucked tail and split town, leaving angry backers and regretful neighbors. “I wanted to see it work; it would have brought more people down here,” a nearby business owner lamented.

Compared to the free-spending West-Ex bunch, Beard and her little group of dreamers are functioning on peanuts. None have deep pockets. All are seeking sponsors — Beard, in fact, has scheduled an all-star benefit concert on Jan. 27, designed to replace the cash flow lost when a sponsor bowed out. Web sites like Borchert’s also typically face the challenge of lassoing money from a society grown accustomed to surfing the internet for free. But where all of Taylor’s flash turned out to be a flash in the pan, the smaller, grittier efforts like Borchert’s and Beard’s roll on, bringing new ideas, as opposed to recycled ones, to the Stockyards. And who’s to say they won’t be the ones to give the bigger boost to the historic district in the long run.

The music bug bit Beard early in life and stayed with her after she graduated from Paschal High School in 1973, after she married, after she became a mom. She adored rock ’n’ roll — Peter Frampton in particular. But the Texas Music and Red Dirt genres also clicked with her, from old-school guys like Willie and Waylon to next-generation stars such as Robert Earl Keen. She chaperoned her teenage son, Matt, and his friends to many concerts in the 1990s. “Then it got to the point where I’d say, ‘Pat Green is playing,’ and Matt would say, ‘I’ve got stuff to do,’ and so I’d go on my own,” she said. In 2001, divorced and looking for a place to live, she visited the Reserve at Oak Hill Apartments in the Stonegate area. Playing over the intercom in the main office was Green’s “Songs About Texas,” and Beard took it as a sign that this was the new home for her and Matt, who had turned 18. Their fresh start called out for a housewarming party, and she asked the apartment manager if she could rent the clubhouse for a night. “I was going to get Max Stalling to play, and my apartment was so small,” she said.

Her plan: Charge a $10 cover and give all the money to Stalling, a Dallas-based singer-songwriter she admires. The apartment manager told Beard she could use the clubhouse for free if she made the concert open to all residents. Done deal. Beard and a couple of volunteers, who would later be dubbed the Clubhouse Girls, printed fliers and invited friends. About 50 people showed up, had a great time, and wanted more. The one-time event became a monthly affair. “It snowballed from there,” she said. “People wanted us to do more. We created a web site address, and word spread.”

Her plan: Charge a $10 cover and give all the money to Stalling, a Dallas-based singer-songwriter she admires. The apartment manager told Beard she could use the clubhouse for free if she made the concert open to all residents. Done deal. Beard and a couple of volunteers, who would later be dubbed the Clubhouse Girls, printed fliers and invited friends. About 50 people showed up, had a great time, and wanted more. The one-time event became a monthly affair. “It snowballed from there,” she said. “People wanted us to do more. We created a web site address, and word spread.”

LaRue, Rogers, Bleu Edmondson, and other young artists became fixtures, and those early shows are still talked about with awe. “I was hooked,” said Steve Raines of Aledo, who attended the first show with his wife, Cindy, and has kept returning. “You get to talk to the artists, and they’re really cool guys.”

Even after Beard moved from her apartment to a house in late 2002, she kept using the clubhouse until mid-2003, when 120 people showed up for a gig and almost doubled the occupancy limit. “People were sitting on the floor. You had to step over people, and the air conditioning broke, and it was like 103 degrees in there,” she said. The manager of the Horseman Club happened to be at the show, and he invited Beard to change locations, if she would agree to make it a weekly event. Beard, the manager at a doctor’s office, suddenly found herself scrambling to book and market artists, handle PA systems, set up for Sunday night shows, clean up afterward, and still make it to work every Monday morning with a smile on her face. She relied more than ever on the Clubhouse Girls to keep the ball rolling. “We were just having fun,” Beard said. “We do it all for nothing because we just love the music, and these guys have all become like family.”

The clubhouse intimacy dissipated in the Horseman’s relatively cavernous environs, and Beard couldn’t always rein in the rowdies drinking at the bar. Still, music was the main focus most nights, and the crowds were enjoying themselves. The situation wasn’t perfect, but it was good. In those early years, Beard not only offered gigs in front of rapturous fans, she allowed musicians to flop in her spare bedroom or on couches if they couldn’t afford a hotel room. Ever protective of her son, the teetotaling Beard forbade the hard-charging musicians from using drugs at her house, and most complied. Those who didn’t got uninvited.

LaRue and his bandmates slept there in the early years, including one night when the brakes went out on their van and left them stranded on an I-35 median north of Fort Worth. LaRue telephoned Beard, who hopped in her candy-apple-red convertible Volkswagen and hurried to the rescue. LaRue laughed recently recalling how he and three band members somehow managed to squeeze into her tiny car with their instruments in their laps. “It was like a joke: How many musicians can fit in a Beetle?” he said. “But without hesitation she came and got us. She’s got a wonderful spirit and she’s a great person — a direct descendent of the Dalai Lama!” Rogers was just breaking into the music business when he heard from friends about the Clubhouse shows and sent word that he wanted to play. A mutual love affair developed between him and the crowd. “I didn’t have two pennies to rub together,” he said. “Fifty bucks was a lot of money for me at the time. It seemed like that’s where everybody was hanging out on Sunday nights, playing music for people who paid attention and cared about being there. As a songwriter, it was appealing.”

Nowadays, guys like Rogers and LaRue are in demand across the Southwest and are more likely to play Billy Bob’s Texas when they come through town. Many large venues enforce “radius” clauses that prevent artists from playing at smaller clubs in the area. Rogers, LaRue, and others have graduated from the Clubhouse but were among the first to donate money when Beard sent out an e-mail in December announcing the benefit concert. Rogers sent a $1,000 check and wrote “Love, RRB” (Randy Rogers Band) at the bottom. “I would stick my neck out for her, for what she’s done for the music scene, and every artist that has played for her would tell you the same thing,” he told Fort Worth Weekly.

Beard is often characterized in saintly terms, but she’s no pushover. She can be tough and get her dander up at times and has earned the nickname “Clubhouse Nazi” for shushing overzealous talkers. A few nights ago, a cowboy tried to enter a show without paying. She set him straight, and he started squirming. “I’m with the band,” he sputtered. “You’re not on the list,” she replied, and that was that. Some musicians, particularly those who haven’t yet wrangled an invitation to grace the Clubhouse stage, accuse Beard of playing favorites. Still, Beard is downright angelic in an industry populated by smarmy bar managers with screw-the-artist mentalities. She gives 90 percent of the gate receipts to the headlining musicians, and most of the rest goes to the opening act. At most, she keeps 5 percent for overhead. More than once, she’s pulled money out of her own pocket. “We’re not in it to make money off the musicians,” she said. “Everything we do is for the musicians.”

Word has spread, and artists such as Sweeney and Hood travel from miles around to play the gig. Sweeney was coming off three straight nights of gigs at East Texas honkytonks but drove to the Clubhouse for her debut on a Sunday night just because of its reputation for quiet, passionate crowds. “Everybody says they love it here,” she said. At the end of the night, she and Hood pocketed $278 each. After travel expenses and the cost of side musicians, it wasn’t a bonanza payday but a satisfactory one. Both said they looked forward to returning. The Clubhouse shows relocated in 2004 and again in 2006, but by then Beard had soured on hosting events at public drinking establishments where she couldn’t always enforce the sit-down-and-shut-up rule. In September, she moved to the Upstairs venue, with its homey atmosphere and intimate vibe, but attendance has dropped off. She figures it’s a combination of factors — a shortage of free parking in the Stockyards, the public’s lack of knowledge about the Upstairs venue, and a great year for the Dallas Cowboys, whose Sunday games provide stiff competition for people’s attention. At about the same time, Beard’s primary sponsor, Southern Thread clothing company, pulled out. She’d been depending on the sponsorship to offset overhead costs, and she’s been operating on a wing and a prayer since then. It was time for a benefit concert.

Artists are coming to the rescue, just as Beard has done for them so many times. Stalling, Tommy Alverson, Josh Grider, Walt Wilkins, Owen Temple, Jason Eady, and Rodney Hayden are just some of the musicians who have already promised to perform. Beard has made a deal with Hyatt Place Stockyards (formerly AmeriSuites Hotel) to provide rooms for artists at reduced cost, and she’s looking for a new sponsor. “Slowly, people are learning we’re up there, and if we stick with it, we’re going to be fine,” she said.

Artists are coming to the rescue, just as Beard has done for them so many times. Stalling, Tommy Alverson, Josh Grider, Walt Wilkins, Owen Temple, Jason Eady, and Rodney Hayden are just some of the musicians who have already promised to perform. Beard has made a deal with Hyatt Place Stockyards (formerly AmeriSuites Hotel) to provide rooms for artists at reduced cost, and she’s looking for a new sponsor. “Slowly, people are learning we’re up there, and if we stick with it, we’re going to be fine,” she said.

Brad Hines has become synonymous with the Stockyards and Texas Music, although he took a circuitous path getting there. Ten years ago he was a fixture farther east, fronting an Outlaw band that played regularly and partied heartily at Dallas Alley and other Dallas County venues. Hines’ hair hung well past his shoulder blades and, like most people living on a diet of booze and speed, he was thin, wired, and unpredictable. Divorced from his first wife and missing his daughter, he was barreling headlong down a dead-end road. But that lifestyle ended in the late 1990s after he remarried, had two more children, rediscovered his love of God, and stopped using drugs and alcohol. Now his affiliation with the White Elephant keeps him performing on stage or mixing sound at the club almost every night, and he’s well known and respected among fellow musicians and patrons alike.

In addition to his spiritual growth, he’s doubled in size physically in the past decade, making him a Stockyards Buddha of sorts, dispensing wisdom, keeping a lid on his ego, advising younger artists, and refining a keen ability to cut through bullcorn. That’s why Borchert chose to partner with him on Hi-IQ Music, a business venture intended to spotlight artists and help put some jingle in their pockets. “After an extensive amount of searching, I decided Brad Hines was the right guy,” Borchert said. “The music business is fraught with dead ends and ambushes, and Brad is a great compass. He is a very moral guy and always does the right thing. My management and technical ability and Brad’s intimacy with the musicians make a real nice combination.”

Borchert spent 30 years as a high-tech executive handling product launches and marketing campaigns in Dallas. He’s also a lifelong musician. So when he decided to go out on his own in the business world, he wove all those threads together. In the past year or so, high-quality streaming videos and the technology needed to receive and appreciate them have become commonplace, with broadband and wi-fi service now available in most residential areas, offices, and even cafés.

“That technology has enabled the delivery of this kind of content, competing with radio and TV,” he said. “That’s the big bang that all media is going through, the fact that the internet is the ubiquitous channel for delivery of this type of content.”

For musicians, the process of spreading the word in recent decades has consisted of endless touring and scrambling to get on commercial radio. Borchert envisions an alternative method based on exclusive full-length concert videos available online 24-7. Viewers experience the artists through interviews and intimate gigs with between-song patter — content available only on the site. Fans can also order CDs and merchandise, look at touring schedules, communicate through blogs, and become part of a community of musicians. “There is an enormous explosion of people going online and watching videos,” Borchert said. “This is an alternate way for artists to present themselves in a very rich way, with a high level of customer involvement, sights, sounds, engagement.” By comparison, he said, “Radio’s got one dimension — audio.”

The first individual profile on the Hi-IQ Music mother ship is bradhinestv.com, giving Hines an outlet to post video performances, including the open-mic shows he hosts on Tuesdays at White Elephant. His vision is to spotlight obscure but talented artists who haven’t yet managed to impress the commercial radio gods. “Everybody I know is sick of the radio stations because they’re not doing the promotions [of the artists], and they don’t have the power they used to have,” Hines said. “The shift is to iPods and satellite radio. People have more to choose from. The independent scene is where it’s at right now.”

Borchert is seeking other musicians with similar work ethic, talent, and willingness to promote the site, which is fine and dandy for the artists but so far hasn’t padded Borchert’s bank account. He figures the best way to make a salary is to find sponsors willing to put up money in exchange for advertisements. “We are in the process of doing some picking and choosing,” he said. “People are recognizing the business model and saying, yes, that’s an attractive thing.” While nobody’s handed him any stacks of green yet, he’s confident the site will become popular enough to entice sponsors. He tracks the site visits and said the average viewing time is more than 20 minutes, which is important to advertisers. He chose the site’s name — Hi-IQ — to emphasize a desire to promote literate music by artists with something to say and to do it in a technologically savvy manner. “If you want to watch goofy people pulling down their pants and making funny noises, go to YouTube,” he said. “We would like to be remembered as a founding entity that changed the way music is produced, created, and enjoyed.”

Borchert is seeking other musicians with similar work ethic, talent, and willingness to promote the site, which is fine and dandy for the artists but so far hasn’t padded Borchert’s bank account. He figures the best way to make a salary is to find sponsors willing to put up money in exchange for advertisements. “We are in the process of doing some picking and choosing,” he said. “People are recognizing the business model and saying, yes, that’s an attractive thing.” While nobody’s handed him any stacks of green yet, he’s confident the site will become popular enough to entice sponsors. He tracks the site visits and said the average viewing time is more than 20 minutes, which is important to advertisers. He chose the site’s name — Hi-IQ — to emphasize a desire to promote literate music by artists with something to say and to do it in a technologically savvy manner. “If you want to watch goofy people pulling down their pants and making funny noises, go to YouTube,” he said. “We would like to be remembered as a founding entity that changed the way music is produced, created, and enjoyed.”

Independent artists such as LaRue look at Hi-IQ as a way to get marketed in an innovative manner that appeals to a generation more at home with listening to music on a computer than spinning a CD. “That’s the next level; that’s how everything grows,” he said. How big it will grow and what impact it will have remains to be seen. The Stockyards district is a notorious minefield, and plenty of dreamers and entrepreneurs have become just so many notches on Fate’s eager pistol. But don’t tell that to Beard, Borchert, Hines, and the rest. Dreamers driven by passion rather than greed have a tendency to feel bulletproof and see lots of silver lining with very little cloud. “The web site is going to allow people to see what we do, see what it’s like in a listening venue, and it’s going to make people want to go to the shows,” Beard said. “You get to hear the stories from the artists and why they wrote a song. It’s great for the fans and great for the artists.”

In the end, it could be great for the Stockyards and Fort Worth as well. If Beard’s and Borchert’s enterprises succeed, they could make Cowtown a player in a new era — Fort Worth, where the West begins and where entrepreneurs spurred the music industry in a new direction.

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.