No matter how long, notated, and well written an artist’s statement is, his or her art –– to paraphrase Sir Duke –– don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.

Conjoined black canes hanging from a small, translucent ledge near a gallery’s ceiling suck any semblance of aforementioned “swing” from the ether. Whoosh! Like a black hole swallowing light, Richard Wentworth’s “Thus,” hanging –– inertly –– now as part of the group show where is the power at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, flips the script on postmodern conceptualization (and, a’hem, some critics’ thoughts about it). Maybe hucksterism is the artwork’s point. Maybe you’re supposed to look up at Wentworth’s canes –– just two black walking sticks –– and think, “Gosh, that is so freaking dumb.” But to what end? What is accomplished by an aesthetically inutile postmodern artwork in which postmodern art’s aesthetic inutility is underlined? Another dissertation? Please, spare us.

Through the end of October, where is the power offers Fort Worth’s über-traditional art scene a much needed jolt but doesn’t shine. The show is not offensive or amateurish, just maddeningly undercooked and minimalist almost to the point of infinitesimalism.

Guest-curated by one of Fort Worth’s brightest artistic minds, Terri Thornton, education curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, where is the power is definitely unlike anything you’d see anywhere else in town (except maybe at the long-defunct Four Walls), which is a major plus. Walking into the show, frankly, is like being transported from “Cowtown” (ugh; hate that term) to the hippest gallery in New York City. The art in where is the power is that outré and that finely, super-professionally produced, displayed, and marketed. Fort Worth desperately needs more avant-gardism. Kudos to Thornton and FWCA for dragging us out of the manure and into at least the 1960s. But does where is the power swing? Ehhh.

Let’s skip the subtext and simply observe, like folks did back in pre-postmodern days. One of the most traditionally attractive, innovative pieces is Robert Kinmont’s “127 Willow Forks (This Is Who I Am),” three orderly rows of forked willow branches hanging by threads, above a box of additional branches on the floor. The chorus of “Y” shapes teases out an interrogative mood –– why, why, WHY don’t we know where the power is?! (har, har) –– and the piece’s organic nature and found-object origins make for a much-needed lighthearted respite in such a heady, sterile context.

Another outstanding piece is equally aseptic and intellectually robust. Mona Hatoum’s “Projection” is simply a white and off-white recreation of the Gall-Peters projection, a world map in which each continent is sized to scale –– North America isn’t as big as most other maps may lead you to believe. The piece simply looks like a large sheet of white paper with shapes skillfully torn out. Like Chris Powell’s “twin,” two chairs smoothly plastered back to back, “Projection” has an undeniable, intoxicating tactility.

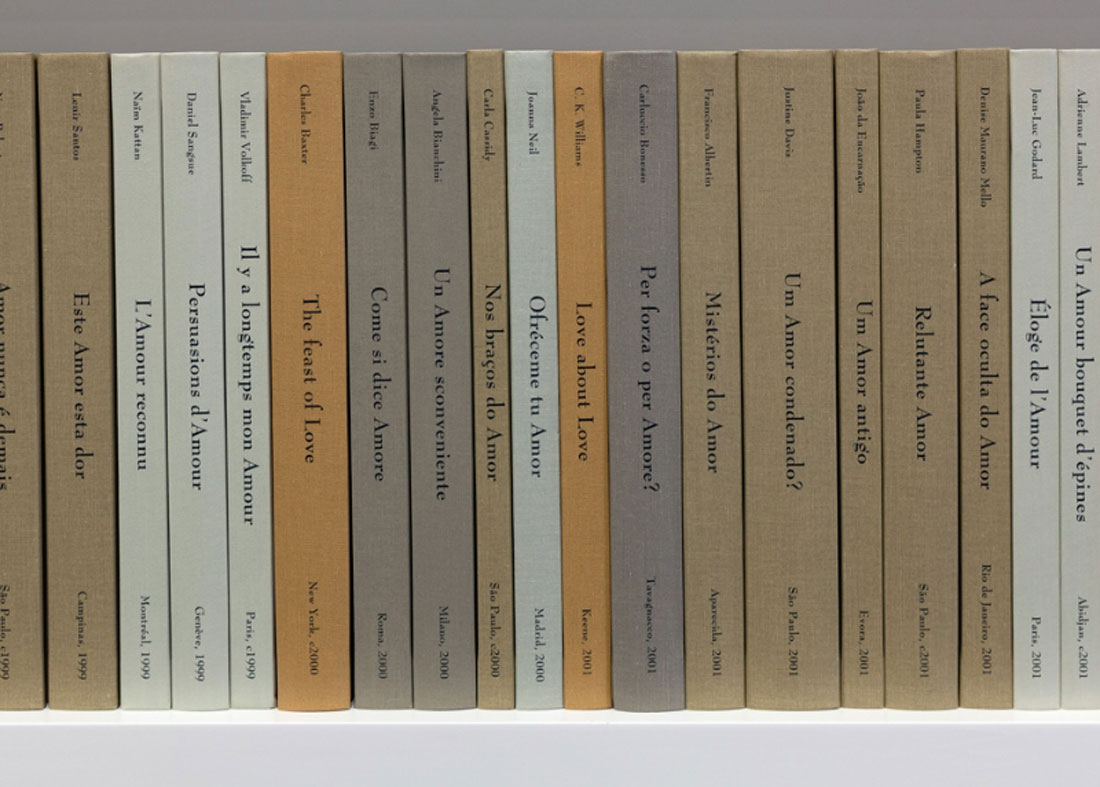

Perhaps the exhibit’s most memorable work is Valeska Soares’ “Love Stories II”: 250 similarly hued books (brown, gold, and gray) bearing romantic titles in multiple languages, neatly stacked on two long white shelves. Located by the gallery entrance, the piece, with its enticing promises of love and transportative storytelling, is situated to stop viewers in their tracks.

Though you can’t touch the books and can’t tell simply by looking at them as they are arranged, their pages are blank. How do we know they’re empty? We’ve read about it.

In a handsomely designed foldout, Thorton offers a long, notated, well written essay describing the exhibit’s origins and intellectual underpinnings. The literature –– which under any other circumstances would be considered ponderous and unwieldy –– ends up being responsible for entirely too much of the exhibit’s success. Shouldn’t great art be allowed to speak for itself?

One interesting point that Thorton raises deals with the show’s title. Astute observers may notice the lack of a question mark. Thornton –– and, by extension, the fine folks at FWCA –– are much too smart, much too discriminating to thumb their noses at such a simple yet significant grammatical rule. Maybe Thornton is asking us to whip out our maps. Maybe the title, she writes, can be rewritten to read, “being in certain locations or in a certain location is the power.”

Perhaps the most creative answer to that non-question –– in theory –– is Kris Pierce’s “The Red Telephone,” a meta-triptych of three payphones in town that the artist has transformed into red-hued “public confessionals that, streamed to a web-based station, disclose dialogue,” Thorton writes. One is located inside the new hotspot The Gold Standard (2700 W. 7th St.). Nothing came through the earpiece on a recent afternoon visit, but maybe nothing is supposed to. Who knows! However, after whipping out his smartphone and following the url posted on the phone box (theredtelephone.net), your intrepid reporter discovered the artwork’s “archives.” The most recent clip consists of four voice recordings: a young woman claiming she’s wasted, a dude extending an apology to someone he’s hurt, and a guy who sounds much too sincere for comfort trying to pawn off some backstage passes to the circus.

The first voice, though, says the most.

“Hello?” a young woman says, genuinely perplexed. “Hello?!”

She pauses long, thinking. Finally, she cries, “I don’t know what I’m doing!”

(Kris? Is that you? Ah! Just kiddin’!)

Art about art is kind of like garnish: It’s necessary but mostly useless. Philosophers, critics, and other people who live in their parents’ basement have used art about art –– a.k.a. conceptual art –– to launch a million theories. Over time, they have either helped enlighten us, paving the way for such mainstream-ish masters as John Currin and Vernon Fisher, or have unwittingly opened the door to charlatanism. When the only thing that separates a conceptual artist from your garden variety wacko on the street is a sheet of paper reading, “Master of Fine Arts,” then philosophers and critics –– and other artists –– must set down their meerschaum pipes, roll up the sleeves on their cardigan sweaters, and take a stand.

[box_info]

where is the power

Thru Oct 27 at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, 2900 W Berry St, FW. Free. 817-257-7643.

[/box_info]

Fucking Brilliant.

Also, though, as a progenitor of said conceptual, aka, bullshit art myself, I have to say that I like to cap off my psudo-intellectualism with a little sprankle of ” I’m just fucking with you”, which in this case, these folks ain’t! This ish is for real. Respect the art!

A little bit of I’m-just-fucking-with-you is tantamount to “swing.” I’ll take it.