I’m thoroughly confused about the spelling of the name of Calvin’s estate. The DVD chapter heading has it “Candieland,” but the English-language subtitles render it as “Candyland.” Meanwhile, my original review made it “Candie Land.” I’m going with “Candyland” now.

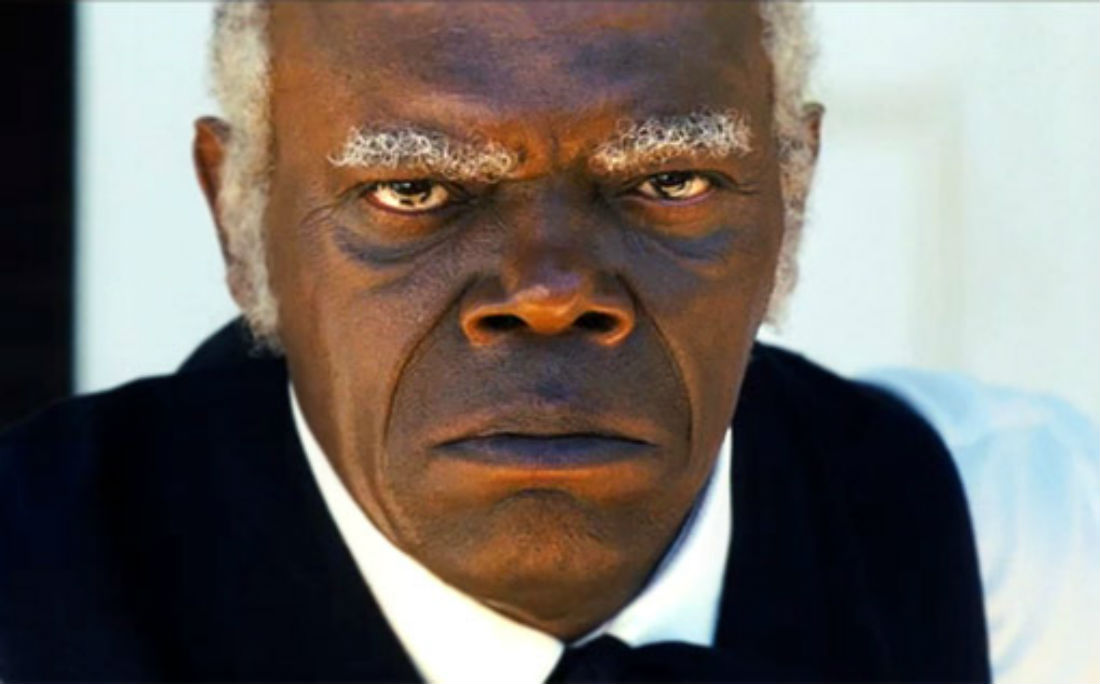

• Jerry Goldsmith’s “Nicaragua” from the 1983 thriller Under Fire plays on the soundtrack as the entourage rides to Candyland. We see a closeup of a black person’s hand signing Candie’s name to a $65 check to a Harris Feed Co. It’s Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), an elderly slave with a balding pate and white sideburns and brows.

• The estate is a beautiful, open, inviting place, but the music (another march with a slow, heavy tempo) clues us in that we’re approaching the den of iniquity. We see a white woman (Laura Cayouette) whom we presume to be mistress of the house and a smiling black woman (Dana Gourrier) who looks to be a housekeeper or in some equivalent position of domestic power. They’re both beaming down at the approaching retinue. Candie’s carriage rides in front while Django and Schultz ride side by side behind them. Django looks to his right and has another vision of Hildy in that yellow dress, waving to him. The real Hildy is closer by than he thinks.

• The Mandingo fighters are herded into a line to one side of the front door. Stephen rises up out of his chair and comes out to greet the master. His eyes widen at the sight of Django riding in on a horse, then narrow with anger. I really should have had this character pegged from the start, but more on that later. So it begins…

• Rodney’s glowering at Django angrily, too. Calvin greets Stephen, and the latter responds, “Yeah, yeah. Hello, my ass.” I could always feel audience bracing themselves for a typically Samuel L. Jackson loud and brash performance at this line, and I was bracing for one, too, when I first saw this, but this is something else, as we’ll see. Stephen asks, “Who this nigger up on that nag?” Calvin banters with Stephen. “You have nails for breakfast? … Why you so ornery? Did you miss me?” This sends Stephen into a whole routine about how much he misses the master (“like a hog miss slop!”) before he repeats his question from before, “Who this nigger on that nag?” At this point Django quietly jumps in: “Hey Snowball, wanna know my name or the name of my horse, you ask me.” Walking with a cane, Stephen starts in on our hero, “Who you callin’ ‘Snowball,’ Horse Boy?” and threatens to pull him off his horse just as Django did to Hoot earlier. Calvin intercedes at this point and says, “Let’s keep it funny. Django is a freeman.” Stephen can’t believe this, but Calvin makes the introduction. “Django, this is another cheeky black bugger like yourself, Stephen. Stephen, this here’s Django. You two oughta hate each other.” He is right about that last bit. Calvin further explains that Django and Schultz are customers. “And you, you old decrepit bastard, oughta show them every hospitality,” he tells Stephen affectionately. Stephen doesn’t know why he has to serve Django, but Calvin says he doesn’t need to know why and orders Stephen to get two guest bedrooms ready. This makes Stephen even more apoplectic. “He gonna stay in the Big House?” Calvin explains that it’s different for a slaver, and asks if Stephen has a problem. “Oh no, I ain’t got no problem with it, if you ain’t got no problem burnin’ the beds, the sheets, the pillowcases, everything else when this black-ass motherfucker’s gone!” I saw this movie with white audiences, black audiences, and mixed audiences, and they had different reactions to individual scenes, but the reaction to this was always the same particular sort of laughter that’s mixed with outrage. Calvin finally loses his patience with Stephen at this point and orders the old man to get the rooms ready. Stephen agrees and walks off muttering, “Can’t believe he brought a nigger to stay in the Big House. His daddy rollin’ over in his goddamned grave!” Moguy and Calvin agree that Stephen’s behavior is getting worse.

• With Stephen gone off, Calvin stands up in his carriage and screams, “Where is my beautiful sister?” The white woman we saw earlier comes flouncing out. Calvin introduces to Schultz his widowed sister, Lara Lee Candie-Fitzwilly. Wonder what happened to the husband. Maybe Calvin had him killed so he’d have her to himself. He kisses his sister on both cheeks and calls her “a tonic for tired eyes.” Meanwhile a couple of overseers pick three of the slaves out of the line of fighters and make them run across a field, shouting “Niggers don’t walk around here, niggers run!”

• As the party is entering the house, Schultz asks Calvin about Hildy. Their preceding conversation which we didn’t see appears to have slipped Calvin’s mind, but Schultz asks if she can be sent to his room before the fighters give demonstrations. Calvin agrees with a little laugh, as if he knows what Schultz really wants, and tells Stephen, who has returned, to get Hildy cleaned up and sent to Schultz’ room. Stephen stammers out that she’s in the hot box, pointing to a metal cellar built into the ground outside the front door. (Anachronism watch: While this form of punishment was in use in the 19th century, it was typically reserved for prisoners in the South. Punishments for runaway slaves could be far more hideous.) Calvin asks why she’s there, and Stephen says she ran away again. Seeing the hot box, Django takes off his shades and puts his hand on his pistol, though no one notices this. Thinking of D’Artagnan, Calvin asks Stephen in an exasperated tone how many people ran away in his absence. Stephen says it was just the two. Calvin asks whether Stonesipher’s dogs tore her up, and Django looks ready to waste everybody right there, but Stephen reports that the dogs were busy chasing D’Artagnan, so the only damage Hildy has incurred is from running through bushes. At this Django, uncocks his pistol and relaxes. Hildy has been in the hot box all day and has 10 more days to go, but Calvin orders her taken out. Once more, Stephen is outraged, and he protests. Calvin says, “Jesus Christ, Stephen! What is the point of havin’ a nigger that speaks German if you can’t wheel ‘em out when you have a German guest?” Stephen acquiesces again, and Calvin places Lara Lee and Cora (the slave woman we saw next to Lara Lee earlier) in charge of making Hildy presentable. He then issues apologies to his guests, saying he’s going off to rest from his travels. He then kisses his sister on the lips before going in. If this gets any more incestuous, a Game of Thrones episode is going to break out.

• Stephen orders the overseers to get Hildy out of the box and repeats Calvin’s orders to Cora, mispronouncing Schultz’ last name as “Shoots.” Django walks several steps toward the box to see his lady love for the first time in however long it has been. Three white men (one with a rifle) walk over to the box in slow motion, while looking on is an artfully arranged tableau of Django in the foreground, Schultz in the background, and Stephen and Lara Lee on the top step in the deep background. One of the men draws a bucket of water from a nearby well, while another takes out the big metal pin that’s holding the door shut. In close-up, we see Django steeling himself, knowing she won’t be in good shape. The men open the door and splash a naked Hildy with the water. She screams. They grab her and place her in a wheelbarrow as she screams incoherently. The slow guitar music on the soundtrack gives the scene a sad, elegiac tone. This is promptly punctured by Stephen, who asks Django if he intends to sleep in that box. The whip zoom goes in Django’s angry face.

• Ennio Morricone’s song “Ancora Qui,” composed for the film, plays on the soundtrack while a group of slave men place candelabras on the dinner table and a group of women lay out napkins and silverware. They do so with military-like precision. A slow tracking shot through the hallways shows us women lighting candles, signaling us that it is now evening. Read the translation of that song’s Italian lyrics into English, and you’ll find the words (the first verse especially) appropriate to the situation. Morricone is a highly prolific composer, but Tarantino likely called on him for his work on spaghetti Westerns in the 1970s, including My Name Is Nobody, The Hills Run Red, and The Return of Ringo. More recently, he scored Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. Morricone caused a minor flap while talking to Italian students about Tarantino’s use of music, but apparently there are no hard feelings between the artists.

• Holding a candelabrum, Lara Lee leads a cleaned-up Hildy to Schultz’ room, with Cora bringing up the rear. Hildy’s hair is pulled into a double bun. When they reach Schultz’ door, Cora adjusts the back of her dress, calling our attention to the fact that said dress mostly but not completely hides the whip marks on her back. Lara Lee exhales before knocking on the door.

• Schultz opens his door partially and greets them, “Hello, ladies,” even though the following POV shot reveals that he can only see Lara Lee at that point. As Lara Lee makes the introduction, Schultz opens the door the rest of the way, and we can see that he’s struck by her beauty as she curtsies to him. As he says how much he has heard about Hildy, Lara Lee says, “Well, it’s not every nigger who speaks German, don’t ya know.” The fleeting look of contempt that crosses Waltz’ face at this point speaks volumes. He switches back to sincerity as he says, “As I look at you now, Broomhilda, I can see all the passions you inspire are completely justified.” She’s somewhat frightened here, but this catches her attention. Lara Lee tells her to speak German. Hildy comes up with a standard line and Schultz feigns astonishment. He invites her into his room, and Lara Lee gives her the candelabrum in her hand. She starts to say something else to Schultz, but the doctor just shuts the door in her face.

• In German, Schultz offers her a glass of water. He pours her one, and she sets down the candelabrum on a nearby dresser to take it. As he hands her the glass, he tells her in both German and English not to be afraid, since she probably thinks she’s being called to his room to have sex with him. He then goes over and starts making up the bed, which presumably he has been lying in after his travels. He tells her that he’ll speak slowly, since she hasn’t spoken German in a while. Further, he tells her that they’re only speaking in German in case Calvin has spies listening in. He puts his jacket on, then asks for pardon after realizing that he doesn’t have his customary cravat handy. Vainly smoothing out his hair, mustache, and beard, he takes a seat on a chest at the foot of the bed. He continues in German that he and a mutual friend of theirs have traveled a long way to find Hildy and rescue her. He tells her to take a drink, and she does so, looking like she forgot she had the glass in her hand amid her astonishment. She protests that she has no friends, but Schultz chuckles and says she does. Clearly taking pleasure in this little coup de théâtre, he says he can’t tell her who it is yet. “Our mutual friend has a flair for the dramatic.” He tells her that the friend is standing behind the door, and indeed a nervous-looking Django is there. Schultz makes her promise not to scream, and she promises. Schultz then moves to knock on the bed-post, waiting for her to nod before he does so. The door opens, and there stands Django, with a light in the hallway behind him giving his appearance an unreal glow. He just says, “Hey, Little Troublemaker.” Hildy gasps, spills the rest of the water in the glass, and faints in a delicately choreographed way that jibes with the fantasy aspects of this movie. Schultz then provides the kicker, looking at Django and saying, “You silver-tongued devil, you.”

• Candyland’s kitchen is bustling with activity, as Cora tells one house slave that the guests are drinking tonight, so he should get a big jug of Calvin’s favorite red wine. Walking through, Stephen tells Cora, “Get your big pretty ass out of the way.” Cora flirts back, “You know you like it.” Stephen laughs and flirts back as he walks through the door into the dining room. Apparently the aforementioned fighting demonstration has already taken place, and now everyone is having dinner. A tracking shot follows Stephen into the room as Schultz tells Calvin that the best specimens were Samson, Goldie, and Eskimo Joe. The dinner guests are eating steak with mashed potatoes on the side, and glasses of both red wine and iced tea to drink, a very Southern touch. Schultz asks why he’s called Eskimo Joe. Calvin responds, “You never know how these nigger nicknames get started. His name was Joe. Maybe one day he said he was cold. Who knows?” Schultz praises Samson as a champion, but Calvin corrects him that all three fighters are champions. Django then corrects him: “Samson’s a champion. Them other two pretty good.” We see three slave women waiting on the guests look up in surprise at hearing the master contradicted by a black man. Standing by Calvin’s seat, Stephen starts to protest, but Calvin says it’s all right. Schultz continues that he has experience in European traveling circus and already has ideas about how to promote his fighter. Hildy is working dinner service, likely at Schultz’ request. She tries to pour gravy for Calvin, but without looking at her, he taps the gravy boat with his knife to indicate that he doesn’t want any. Stephen silently signals her back into the kitchen, and she and Django exchange looks before she goes in. Schultz says, “I need to have more than just a big nigger. He needs to have panache.” Stephen doesn’t know what that is. Calvin tries to explain but can’t come up with a definition, so he throws it to Schultz, who says, “A sense of showmanship. I want to be able to bill him as The Black Hercules.” This last gets a chuckle from everyone else around the table (which includes Lara Lee and Moguy). Stephen says, “More like Nigger-les,” and laughs loudest at his own joke. Audiences I saw this movie with laughed even louder, though it was the same sort of laughter tinged with “Can you believe this Uncle Tom?” sentiment that I mentioned earlier. Schultz says he wants to pay, but only for the right fighter. Speaking as an expert would to a neophyte, Calvin tells him that while showmanship is important, the most important thing is being able to win fights. Stephen acts like the congregation in a choir, affirming the truth of everything Calvin says.

• The n-word is flying thick and fast in this scene, and when I first saw the movie, I could sense the audience (made up of my fellow film critics, augmented by our friends from the African-American press) growing uneasy because of it. This is as good a time as any for me to discuss the way the movie uses the word “nigger.” As someone pointed out, this movie may drop that offending word more than 100 times, but you still never quite get used to it. It prompted a furious debate among African-Americans about Tarantino’s use of the word. Jelani Cobb’s post at The New Yorker reflected unease about its prevalence, even though Cobb’s issues with the movie largely lay elsewhere. Meanwhile, Steven Boone offered a full-throated defense at Indiewire, while Candace Allen at The Guardian noted that objections to the language were mostly coming from an older generation of African-Americans. The most perspicacious thing I read about the movie’s use of the word came from Rembert Browne at Grantland, saying these discussions about race are quickly becoming more open. Meanwhile, some of the white press tried to stay out of the way, with comical results in Houston film critic Jake Hamilton’s infamous interview with Jackson. A complicating factor is Tarantino’s long-cultivated reputation as a self-styled bad-boy provocateur, and his history of using the word in previous movies like Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown. That lent some ammunition to the movie’s detractors that they might not have had if this movie had been directed by someone like Steven Spielberg, though let’s remember that when Spielberg directed The Color Purple back in 1985, some African-Americans accused him of overstepping: Who does he think he is, this Jewish boy whose best movie was about a shark? That, of course, hooked into a larger debate over who has the right to tell stories about slavery. I’m usually content to stay out of the ongoing debate over this word myself. I do understand the thinking of the camp that says the word is derogatory and should disappear, and the thinking of the other camp that says the word should be reclaimed and appropriated for use among African-Americans. Still, I can’t do a series of blog posts like this without addressing the issue. One defense of Tarantino’s use of the racial slur is that white people (even ones who detested slavery like Mark Twain) used the word commonly in the 19th century. The response to that would be that this movie is making few pretenses to historical accuracy, but that’s a double-edged sentiment. After all, you can’t criticize the movie for being unrealistic and then also criticize it for using the word “nigger” as often as it does. My defense would be something I mentioned in my original review; indeed, I’m surprised that more people didn’t pick up on this. The use of the word “nigger” is a form of violence that goes hand in hand with the movie’s physical violence. Using the word helps the white slaveowners view the African-Americans as less than human. In Tarantino’s other movies, the word “nigger” is used in the ways that it’s used in contemporary society, as a term of affection, as a satirical term, as a point of reference, as a synonym for “man,” as an expression of brotherhood, and as a slur. In this movie, the villains only use it in its derogatory sense, and its preponderance helps establish the world of the film as a place where racial violence is commonplace, widespread, and mostly unpunished. In other words, the way the slaveholding South actually was. Against this backdrop, Schultz uses it to pose as a racist white man, as I mentioned earlier. Django uses it because he can’t imagine himself as anything else. And here’s where Tarantino missed a huge opportunity. At the movie’s end, he could have had a free Django say, “I ain’t a nigger no more” or words to that effect. It would have defused much of the criticism in advance, it would have effectively countered what we heard before, and it would have brought the house down in many theaters. As for the issue of whether Tarantino should have made this film, I get nervous when I hear that certain subjects can only be addressed by certain artists, especially when it’s something like skin color that’s separating who has the right and who doesn’t. Sometimes artists do choose their subjects quite stupidly, but a free society must allow them to do so, even if it upsets large numbers of people. Having said that, many observers made the obvious and completely accurate point that no African-American filmmaker today would have been given $100 million (the estimated budget for Django Unchained) by a major studio to make an extravagant, wildly imaginative historical fantasia about slavery. In our supposedly enlightened age, that is where we are.

• Hildy has come back into the dining room and is now holding the wine decanter, and Schultz signals her to fill his glass. As she does, he whispers something in German to her and she laughs. Calvin notes this. Schultz says, “Oh, Monsieur Candie, you can’t imagine what it’s like not to hear your native tongue in four years.” Calvin answers, “Well, hell, I can’t imagine two weeks in Boston.” This makes everyone except Django laugh, with Stephen laughing loudest and Moguy choking on his food. Schultz continues, saying how happy he was to speak German again and how charming Hildy is. Calvin says, “Now, be careful, Dr. Schultz. You mighta caught yourself a little dose of nigger love. Nigger love’s a powerful emotion, boy. It’s like a pool of black tar. Once it catches your ass, you’re caught.” Lara Lee thinks that Hildy is more interested in Django. Schultz raises his eyebrows and Django looks away, but it’s Hildy’s shocked reaction that probably gives the game away. Schultz recovers quickest and says Hildy’s probably more interested in a vigorous young man like Django than an old man like himself. While Calvin assures Schultz that he’s still alluring to women, Hildy goes back into the kitchen. Realizing something, Stephen follows her.

• In the kitchen, Stephen gets in her face. “You know that nigger, don’t you?” Hildy tries to play innocent, but she’s really no match for the wily old man. He says, “You wouldn’t lie to me now, would you?” Terrified, Hildy shakes her head. Feigning satisfaction, Stephen walks out. Some critics were displeased with Hildy’s part here, and I have to say I’m one of them. There was a subplot cut out of the film that followed her travels after being separated from Django. It would have been nice to have, but it wouldn’t have solved the basic problem here: Hildy contributes very little to her own liberation, and while her passivity makes the movie line up with the fairy tales it’s modeled on (especially the story of Siegfried and Brünnhilde), it’s a waste of Kerry Washington’s talents. Oh, well. At least we get to see her kick ass and take names every week on Scandal. I’m glad she finally found a vehicle worthy of her.

• Back in the dining room, Django is playing it cool, saying that Eskimo Joe is good, but not worth $12,000. Schultz asks him what he’d pay. Django says $9,000. Calvin makes the excellent point that Schultz came to him wanting to buy, and furthermore claims that he could sell Eskimo Joe for $9,000 any time. Schultz takes a breath and praises Calvin’s powers of persuasion, buttering up Calvin’s ego by making it seem as if Calvin’s brilliant negotiating skills are responsible for talking Schultz into paying the $12,000 that he was willing to pay in the first place. What’s more, he’s playing it as if he’s going against his expert’s advice to overpay. He bangs the table and agrees to pay $12,000. Calvin is pleased with himself. Schultz points out that such a huge deal will need to be gone over by the lawyers, namely Moguy and Schultz’ own man, “a persnickety man named Tuttle.” It’ll also require a doctor’s examination of Eskimo Joe. He asks to return to Candyland in five days to complete the deal. Schultz is arranging an exit; either this Tuttle fellow will find a hitch that gets Schultz out of paying 12 grand, or Schultz and Django will simply take Hildy and disappear, leaving Calvin holding his third-best fighter. Ignorant of all this, Calvin proposes a toast to “the black Hercules.” Stephen hears this and says, “You was right, doctor. That name do have pan-ass.”

• Calvin asks Hildy to top off his wine and asks her how she likes serving the big table. After some menacing prompting from Stephen, she says she likes it. Calvin makes some disgusting comments about her pleasuring the Mandingos sexually. Django pinches the bridge of his nose. Stephen takes this opportunity to spring his trap, suggesting that the doctor might want to see her back, “seein’ as they don’t have many niggers where he come from.” Calvin thinks this a splendid idea, and after establishing that Schultz didn’t take her clothes off when they were in his room, he tells Hildy to take off her dress. Django is now glaring directly at Calvin. When Lara Lee protests that she went to all the trouble of dressing Hildy up, Calvin answers that Schultz might be interested in seeing the whip marks as a medical man. “I’m sure it would fascinate him, the niggers’ endurance for pain.” Django has his hand on his pistol again. With Hildy looking deeply ashamed, Stephen undoes her dress and turns her around to expose her back, which has four lashes running diagonally across. Calvin is taking unseemly delight in pointing to the scars: “It’s like a paintin’. Look at that.” Finally Lara Lee shuts him down, saying they don’t want to see this while they’re eating. A chastened Calvin offers to defer the show until the after-dinner brandy. Django takes his hand off his gun. Lara Lee orders Cora to lace her dress back up. Stephen grins, having watched Django during all this and seen all he needs to see. Cora comes out, is horrified to see Hildy in a state of deshabille, and takes her into the kitchen.

• Back there, Cora’s advising Hildy to stay on Stephen’s blind side. Speak of the Devil, Stephen comes in and confronts her about knowing Django. She denies it, but she quickly starts to crumble. I like the way Tarantino directs the background extras; a slave woman has been icing a cake, while a man is holding a bunch of carrots, and they are completely frozen as they watch this unfold. The other slaves fear Stephen, as well they should. Stephen asks why Hildy’s crying. She says it’s because he’s scaring her, which is because he’s scary. Amid the silence, the dining-room conversation drifts into the kitchen to the effect that Schultz is praising Hildy’s German skills. Stephen pushes Hildy into a chair and orders her to stay there.

• Schultz reminds Calvin of his willingness to part with Hildy. He’s about to propose to buy Hildy as a throw-in with the deal for Eskimo Joe when Stephen bursts in, yelling at the kitchen staff. Displeased, Calvin tells Stephen that he just interrupted Schultz, and Stephen plays it like his hearing is going. Stephen asks to have a word with Calvin in the kitchen about dessert. Calvin doesn’t want to get up. “It’s white cake! What sort of melodrama could be brewin’ back there?” Stephen pretends to back down, saying he’ll handle the thing himself, but he whispers instructions to Calvin to meet him in the library, which is evidently a code the two men share. Calvin agrees to take a moment. He makes excuses to his guests, saying, “talented as they are, no doubt, in the kitchen, from time to time, adult supervision is required.” DiCaprio’s performance here is loose and funny, and given how tight and intense his performances have been lately, it’s refreshing to see a hint of the matinee idol we saw in Catch Me If You Can and even Titanic. Calvin leaves, standing up and handing his napkin to a slave. As he leaves, the camera lingers on a homoerotic sculpture, placed behind Calvin’s seat at the head of the table. of two naked men wrestling. We hear Calvin ordering his staff to clear the dinner service. The staff files in as Lara Lee asks Schultz for a story about the circus.

• The camera focuses on the back of Stephen’s head as he sits in the library, a similar shot to the one introducing Marsellus in Pulp Fiction. The doors open and Calvin appears, asking what’s up. The camera swivels around to reveal that Stephen’s not only sitting in a chair but is nursing a brandy that he has obviously poured for himself. Here in this private room, we see at last what their relationship is really like, with Calvin addressing Stephen as a valued mentor, and more to the point, an equal. Calmly and quietly, Stephen tells Calvin that their guests are really here to buy “that girl.” Calvin doesn’t even know who Stephen’s referring to, so Stephen clarifies that Hildy and Django know each other. Calvin protests that Schultz just agreed to purchase Eskimo Joe, but Stephen counters that no money has changed hands yet, so there’s no sale. He points out that he just quashed Schultz’ offer, saying “Thank you, Stephen” for his master and then rejoining, “You’re welcome, Calvin.” Calvin can’t understand why they’d do all this for someone as insignificant as Hildy, so Stephen points out that Django’s in love with her and is probably married to her. “Now, why that German gives a fuck who that uppity son of a bitch is in love with, I’m sure I don’t know.” He also says that the Mandingo purchase is just a cover. “You wouldn’t pay no never mind to no $300, but that 12,000? That made you real friendly, now, didn’t it?” We can see Calvin being convinced by all this in stages. He takes in his gullibility with a chuckle and sits back in his chair saying, “Those lying, goddamn time-wastin’ sons of bitches.” He then sits up and claps his hands in anger. “Sons of bitches!” Uh oh. This is where Calvin’s relatively enlightened nature makes him more dangerous. A racist fool like Big Daddy wouldn’t even perceive the double-dealing here, but Calvin does because he has no problem with the idea that a black man has temporarily outsmarted him, or with another black man pointing that out. He accepts that an African-American can be intelligent, but does that bring him around to the idea that slavery is wrong? Of course not! He’s like Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds, a bad guy who realizes that the people he’s stepping on are no worse than himself, a realization that only allows him to trample those people more efficiently. Calvin knows that the system is unfair, but because that unfairness benefits him, he doesn’t care. How many people do we see around us who fit this description? It’s funny; you wouldn’t think of turning to Tarantino’s movies for a critique of capitalism, but Django Unchained offers up a pretty good one anyway. (And how different would this movie have looked if Mitt Romney had won the 2012 presidential election the month before it came out? I can’t imagine, and I’m glad I didn’t have to find out.)

• While Lara Lee concludes a story of hers about her experiences with theatrical folk, Calvin re-enters the room carrying a satchel. He must have been away some time, because she says, “I was beginning to think that you and that old crow run off together.” Calvin laughs at her joke and then sends her out to deal with a slave dealer trying to sell a bunch of women. He rubs her shoulders and kisses her on the cheek, and when she agrees and stands up to leave, he kisses her again twice more. Calvin buttons his coat and carefully folds up his napkin while Schultz breaches the possibility of buying Hildy. Calvin promises that they will momentarily, which makes both Schultz and Django relax, settling in for more boring conversation. They shouldn’t get too comfortable.

• Calvin opens the bag, takes out a small lacquered square of wood, and places it on the table. Then he removes a human skull from the bag and places it on the wood. With Django frowning on, Schultz tries to keep the mood light, chuckling, “Who’s your little friend?” Calvin sits down and quietly says, “This is Ben. He’s a old Joe that lived around here for a long time, and I do mean a long damn time.” He pops his cigarette holder in his mouth, gets out his lighter, and uses it to tap the skull. “Old Ben here took care of my daddy and my daddy’s daddy. Till he up and keeled over one day, Old Ben took care of me.” Calvin flashes a nicotine-stained smile and uses the lighter to light his cig. “Growin’ up the son of a huge plantation owner in Mississippi puts a white man in contact with a whole lotta black faces. I spent my whole life here, right here in Candyland surrounded by black faces. Now, seeing them every day, day in, day out, I only had one question: Why don’t they kill us?” Moguy laughs at this, but a look from Calvin shuts him up. The master continues: “Right out there on that porch, three times a week for 50 years, Old Ben here would shave my daddy with a straight razor. Now, if I was Old Ben, I woulda cut my daddy’s goddamn throat, and it wouldn’t have taken me no 50 years to do it, neither. But he never did. Why not?” He gets up and says, “You see, the science of phrenology is crucial to understanding the separation of our two species.” He removes a handsaw from the bag and says, “In the skull of the African here, the area associated with submissiveness is larger than any human or any other subhuman species on planet Earth.” He starts to saw into the skull, carefully and at different angles to carve out a piece. Schultz looks grossed out, while Django continues looking hostile. When we next see Calvin, his hand is bloody, but this is because Leonardo DiCaprio cut his hand while filming the scene and refused to stop the shoot so it could be attended to. He uses a pair of forceps to pull the skull apart, then to grab the sliver of skull that he sawed out. He points out three indentations on the inside of the skull with a thin metal rod. He says, “Now, if I was holdin’ the skull of an Isaac Newton or Galileo, these three dimples would be found in the area of the skull most associated with creativity. But this is the skull of Old Ben. And in the skull of Old Ben, unburdened by genius, these three dimples exist in the area of the skull most associated with servility.” This is just so much crap as science, but I think it touches something deep in Tarantino’s reason for making movies. This filmmaker has made a career out of flouting decorum and cinematic conventions, and it’s not because he has no use for these things. It’s because he regards these things as the enemy. Politeness and a desire not to rock the boat are what keeps us down, in his estimation. It’s why 19th-century Southerners don’t point out or even understand the moral rot that underlies their society. It’s why we, not just 19th-century African-American slaves but all of us right now, meekly accept injustice and iniquity instead of rising up in protest. That’s why he makes his movies the way he does, with their violence, their disinterest in realism, and their meditations on evil being calculated to affront viewers of every stripe. It wasn’t always the case, but in both Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds, this is what his filmmaking has become, and it is a fascinating and wholly unexpected development. Calvin concludes his anatomy lesson: “Now, Bright Boy, I will admit you are pretty clever, but if I took this hammer here and I bashed in your skull with it, you would have the same three dimples in the same place as Old Ben.”

• Before Django can start anything, Butch bursts through the double doors behind him and Schultz, leveling guns at both of them, and Calvin lets out a mighty roar. He screams at his guests to lay their palms on the tabletop, threatening them with Butch’s sawed-off shotgun if they don’t. This is where I’m in awe of DiCaprio’s performance. Up until now, he’s played Calvin as a pampered rich boy. Yes, we’ve seen him preside over the Mandingo fight, and yes, we’ve seen him order D’Artagnan killed, but he hasn’t yet demonstrated a willingness to get his hands dirty. Until this point in the movie, you could be excused for thinking that Calvin will simply fold up if somebody punches him. Now, though, you see just how truly dangerous Calvin is. He asks Moguy to confiscate their pistols. Making his way to the other side of the table to reach them, the lawyer takes their weapons, begging Schultz’ pardon (“Doctor”) and insulting Django (“Jackass”). Calvin revisits Schultz’ offer to buy Hildy. Stephen marches her in from the kitchen, and Calvin grabs her by the scruff of the neck to get her to sit down in his seat. Stephen makes her lay her hands on the tabletop as well. Calvin says, “Dr. Schultz, in Greenville you yourself said that for the right nigger you’d be willin’ to pay what some may consider a ridiculous amount. To which me myself said, ‘What is your definition of ridiculous?’ To which you said, ‘$12,000.’ Now considerin’ y’all have ridden a whole lot of miles, went through a whole lot of trouble, and done spread a whole lot of bull, to purchase this lovely lady right here, it would appear that Broomhilda is, in fact, the right nigger. And if y’all want to leave Candyland with Broomhilda, the price is $12,000.” Schultz assumes that Calvin is making a flat, nonnegotiable offer. He is. “You see, under the laws of Chickasaw County, Broomhilda here is my property, and I can choose to do with my property whatever I so desire,” he says, smearing the blood from his hand over Hildy’s face. “And if y’all think my price for this nigger here is too steep, what I’m gonna desire to do is…” Calvin carefully sets down his cigarette holder, then picks up the hammer and forces her head down on the table, saying “…take this goddamn hammer here and beat her ass to death with it!” Django stands up, but Butch keeps the shotgun pointed straight at his back. “Then we can examine the three dimples inside Broomhilda’s skull! Now, what’s it gonna be, doc?” Hildy is screaming through all this, and a thoroughly rattled Schultz asks permission to reach inside his pocket for his billfold. He throws the wallet on the table, and Stephen picks it up and counts out $12,000. Calvin is keeping Hildy’s head on the table, with the hammer poised above it, ready to strike. Stephen finishes and throws the wallet back on the table. Calvin smashes the hammer down on the table like an auctioneer, screaming “Sold!” Meanwhile, Hildy just screams, probably thinking that the hammer has come down on her head. Calvin winds up as nastily as he can, “To the man with the exceptional beard and his unexceptional nigger.” He then throws the hammer in Schultz’ direction, and it lands on the table with another crash. Having regained his calm, Calvin starts to dress the wound on his left hand and instructs Moguy to make out a receipt for the sale. With Butch still keeping firearms leveled at both Django and Schultz’ backs, Calvin says, “Now gentlemen, if you care to join me in the parlor, we will be serving white cake.” He’s fully aware of the significance of the “white” in that sentence.

Who is the white lady with the maroon cloth covering her mouth that works on the Candy-land Farm. She appears twice in the movie. First when they are in convoy to Candy-land. She stared him down as if she knew him. He seemed like he recognized her. Then at the end of the movie she finds an old photo graph of a two little children one black and one white, and eyes had a surprising look on them like she knows who he is and is surprised to see him. This is driving me nuts. I have watched this movie twenty plus times trying to see if i have missed something in the movie regarding that women and cant figure it out. If it has something to do with DJANGO part 2, then I cant wait to see it. If it is something I missed in the movie I wish someone would tell me…….