Most people who are even a little familiar with 1960s murder guru Charles Manson know that his apocalyptic worldview was inspired by the New Testament’s book of Revelation and The Beatles’ lyrically cryptic White Album. Few realize that Manson, who’s often been portrayed as a master manipulator, was also hugely influenced by Dale Carnegie’s self-help bestseller How to Win Friends and Influence People. Manson was particularly motivated by Carnegie’s maxim that to get people to do what you wanted, you had to convince them that your idea had originated with them in a flash of “Eureka!” genius.

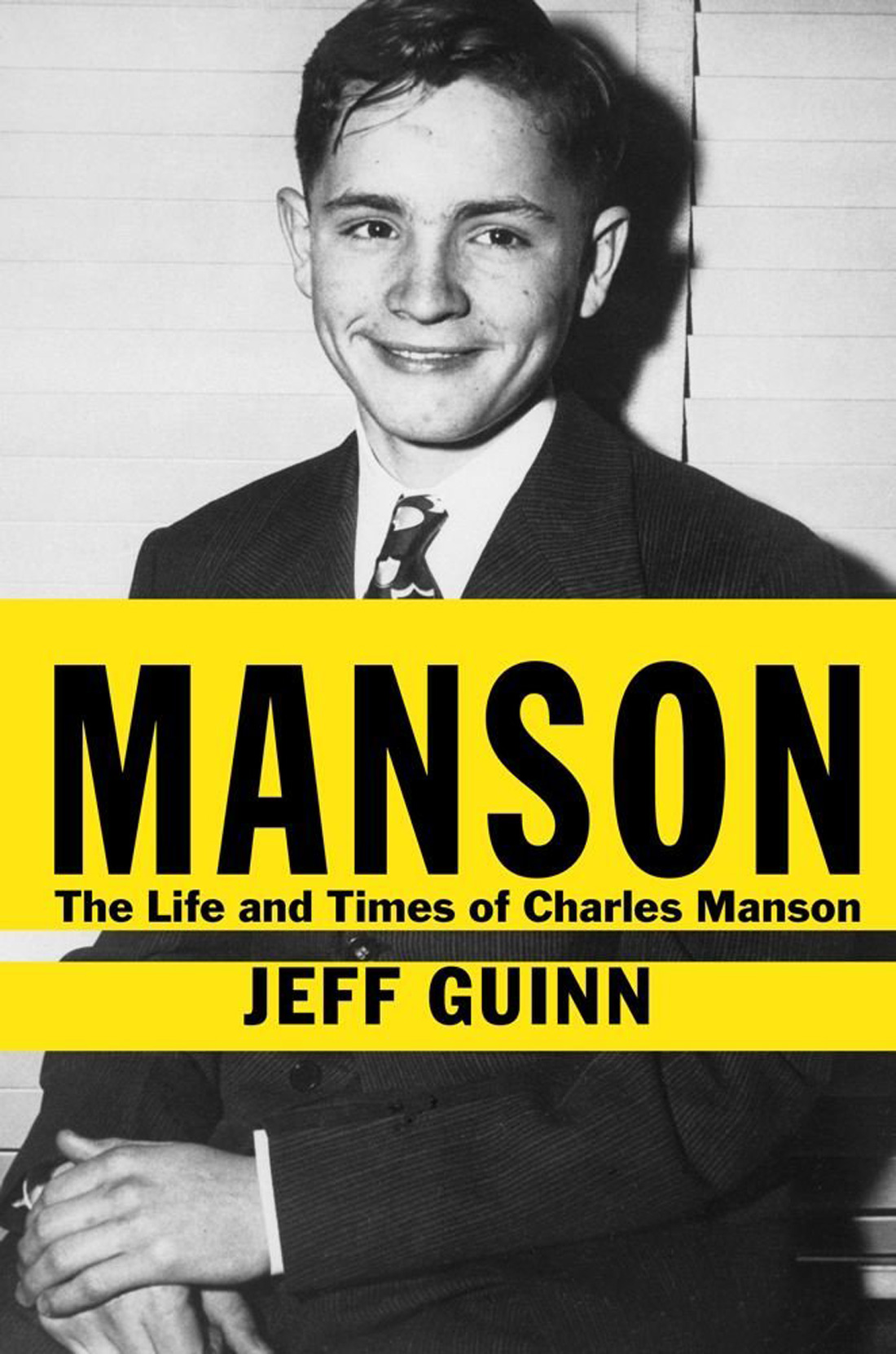

Though there’s nothing funny about the nine horrific murders committed by Manson Family members in 1969 at their leader’s request, it’s hard not to snicker at the pairing of Carnegie, mainstream America’s favorite 20th-century motivational speaker, with the country’s most notorious psychopath. Bringing Manson down to his proper puny size is one of the accomplishments of Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. Fort Worth author and former Star-Telegram staffer Jeff Guinn has done for Manson what he did for North Texas true-crime celebrities Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow in his previous book, Go Down Together: deflated the considerable mythology surrounding his subjects by artfully assembling small, obscure, and fascinating details about their lives into a smart, compelling narrative. It’s a testament to Guinn’s powers as a reporter and a storyteller that Manson, like Go Down Together, manages to feel fresh and (relatively) unpredictable despite the mountains of available information on these bloody outlaws.

Manson was sometimes spoken of by loyal followers and acquaintances as possessing almost supernatural powers of persuasion. Luckily, Guinn wasn’t so impressed –– not by Charlie, a petty criminal and reform-school mainstay from Ohio, nor by the 1960s, a much-feted decade that contained at least as much silly self-indulgence as seminal social upheaval. Guinn demonstrates that Manson’s success as a cult leader had more to do with the sad vulnerability of his followers than with his bizarro mashup of pop music and end-times philosophies. That may sound self-evident, but it’s an important point to make considering how much hype Manson has enjoyed through the decades as some kind of satanic force. And while it’s true that the man was motivated by constant delusions of self-grandiosity, he was less interested in ruling America after instigating his “Helter Skelter” race war than he was in becoming a world-famous rock star. Neither political power nor great wealth interested him nearly as much as old-fashioned celebrity. If American Idol had been around in the late 1960s and Charlie the musician had been accepted as a contestant, would the Tate-LaBianca murders have happened? Guinn makes that apparently silly question entirely plausible with his book, which performs a tidy and much-needed revisionist job on Manson’s scary, otherworldly image.

Guinn interviewed Manson’s sister and cousin for the best parts of Manson, which detail the man’s early formation as a pathological, attention-hungry narcissist. The beatings and rapes he endured as a teen in the Midwestern juvenile prison system of the 1940s and ’50s only fueled his resolve to someday hold real power over others. He followed his hard-drinking mom to California in the early 1960s, where he graduated to stints in federal prison for car theft. In San Quentin, the pimps serving time with him taught Manson practical strategies on how to attract and keep fragile young women. In the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco and, later on, Los Angeles, Charlie found the perfect storm of free love, heavy drugs, and impressionable runaways. Forming a mini-commune called The Family was, in Guinn’s estimation, only a side project to Manson’s feverish ambition to score a record deal. This goal was always paramount and eventually involved super producer Phil Kaufman, Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, and Terry Melcher, a Columbia Records exec and son of Doris Day. Apparently, California rich kids weren’t much better judges of character than the runaways who flocked to the state. Fun fact: Angela Lansbury unknowingly financed some of The Family’s nefarious activities, thanks to her teenage daughter, who let Charlie use her mom’s credit cards but, thankfully, never joined The Family.

If Manson disappoints, it’s because there’s so little about Charlie’s attempts to recreate himself as an environmental activist after the Tate-LaBianca killings landed him his ongoing gig as a prison inmate. Manson refused Guinn’s many interview requests, as he does with most journalists. Guinn surmises, quite reasonably, that he wouldn’t have gleaned much of value from Charlie, anyway. These days Manson mostly just repeats his greatest hits –– making crazy faces and spouting gibberish about God, Satan, and the ego. The victory of Manson is that it methodically and powerfully reminds us Charlie was always a performer of very limited abilities. His success at getting gullible people to do awful things speaks more about the crazy times in which he operated than his own skills.