Judge not a millennial lest ye feel judged when watching American playwright Aaron Posner’s Stupid F*cking Bird, which opened at Stage West Theatre last Saturday. The 21st century adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull pays homage to the dark cheekiness of 19th century Russian drama while relating the existential crises of young millennial characters. Call it pragmatic idealism or lazy whining, new clashes with old in the pursuit of age-old questions about love and artistic forms.

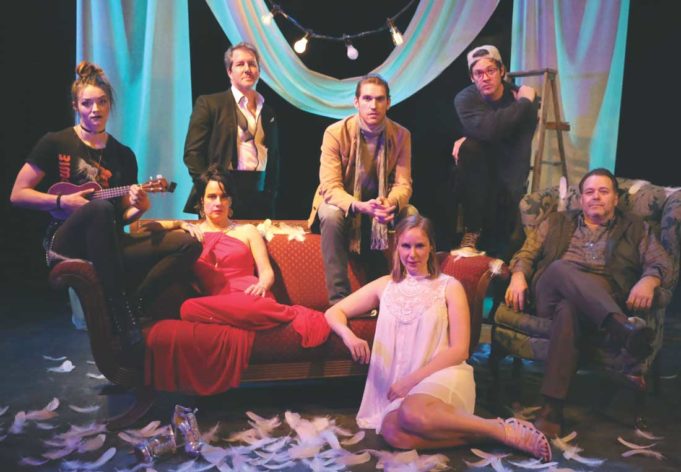

Beginning with a chorus of discontented droning about everything from failed love to flat feet, the characters in this play are introduced in relation to their love triangles that morph into quadrangles as repressed mommy issues unveil the romantic insecurities of an aspiring scriptwriter, Con (Garret Storms), who longs for Nina (Alexandra Lawrence), a simple-minded actress harboring an equal number of daddy issues. Nina lusts after famous author Trig (Chris Hury), who’s involved with Con’s mother, a famous actress named Emma (Laurel Whitsett). Meanwhile, emo stagehand friend Mash (Kelsey Milbourn) hides feelings for Con from everyone but family friend Dev (Matthew Grondin), an oddly sweet geek who relentlessly pursues the affections of Mash. Therapist Sorn (Randy Perlman) provides consolation to everyone but himself as the cast erupts over a meta-theatrical abomination of a play within a play, an affair, and an attempted suicide.

By far the greatest examples of character development come from the most dynamic characters, Con and Mash. Chekhov’s tragic hero, Konstantin, colors the artistic highs and lows of Storms, who navigates the manic depressive swings of his character like a hyperactive squirrel jonesing for Xanax. Milbourn’s gift to the performance is her ability to make whininess endlessly entertaining, especially when she unloads her misanthropic musings on life to the strumming of her ukulele. She lightens up toward the end of the show with a new love, strumming a guitar himself alongside her as they croon to cheerier notions of Buddhist-like acceptance of what discontents them. Dynamic characters shine brightest when dialoguing with simpler characters, making for a successful interplay between foils. Most obviously, the perky, unassuming Nina contrasts to Mash, while the even-keeled Dev rounds out the emotional rollercoastering that makes up Con. Simple characters they may be, they’re believability is accentuated by the sad sagacity of Sorn and the bon-vivant attitudes of Emma and Trig.

What’s most impressive about this cast, though, is that every simple character drives a spike into the funny bone of comedic timing, albeit some are given better punchlines than others. Whitsett runs her lines with memorable raunchiness, but it’s hard to fumble Posner’s wisecracks.

The cast chemistry works mostly because of Director Emily Scott Banks’ adherence to the Meisner technique, a method of acting designed to bring out authentic and potent performances. Look no further than Storm’s bantering with the audience or Lawrence’s ability to level dirty looks at the front row as she intermittently insists, “Don’t judge me.” Both actors engage the emotions of the audience as well as provoking the feelings of the other actors onstage. The entire production becomes something of a guessing game for the audience as the fourth wall falls frequently without warning, making it hard to tell when the actors are speaking in or out of character, but then again, this ambiguity appears intentional.

Set designer Brian Clinnin surpassed the simple flats and furniture aesthetic most designers take with this play, opting instead for a more whimsical birch treescape framed by a swing downstage left, a treehouse downstage right, and a small stage located at left center, on which Con will lose control of his personal dramas. Closer to upstage right, a countryside cottage has been constructed for Emma’s home. Much to the surprise of the audience, the stage rotates to reveal a kitchen interior complete with a kitchen counter, stools, hanging light fixtures, a refrigerator, and other appliances. With every character coming in and out of the kitchen, the drama darkens. When the characters’ metaphorical storm of emotions has passed, the revolve turns once more, sending the characters out into a brighter day. Overhead blue lighting fades as backcloths lift to reveal a gauzier layer of warmly-lit birch trees ensconced with firefly-like points of light.

Not all’s bright that ends brightly. The cast’s chemistry clouds over the stage in an epilogue-like chorus that reveals, somewhat morbidly and rudely, how each character dies but never revealing the underlying message of the play until the last line is spoken. With so many ways to read between Posner’s lines, Stupid F*cking Bird mixes up a cocktail of high emotions that challenge high-brow notions of art and love that millennials and Chekhov would both find palatable.

Stupid F*cking Bird

Thru Feb 19 at Stage West Theatre, 821 W Vickery Blvd, FW. $17-35. 817-784-9378.