Jeff Guinn spends a lot of time with monsters.

An award-winning investigative journalist and member of the Texas Literary Hall of Fame, the Fort Worth writer has spent the last seven years writing great biographies of humanity’s worst. In his 2010 book, Go Down Together, he followed notorious Dallas degenerates Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker from the slums of their youth to their bullet-riddled end. In 2014’s Manson, Guinn traced the life of the granddaddy of all desert demagogues from his tragic boyhood to the murders that ended the 1960s.

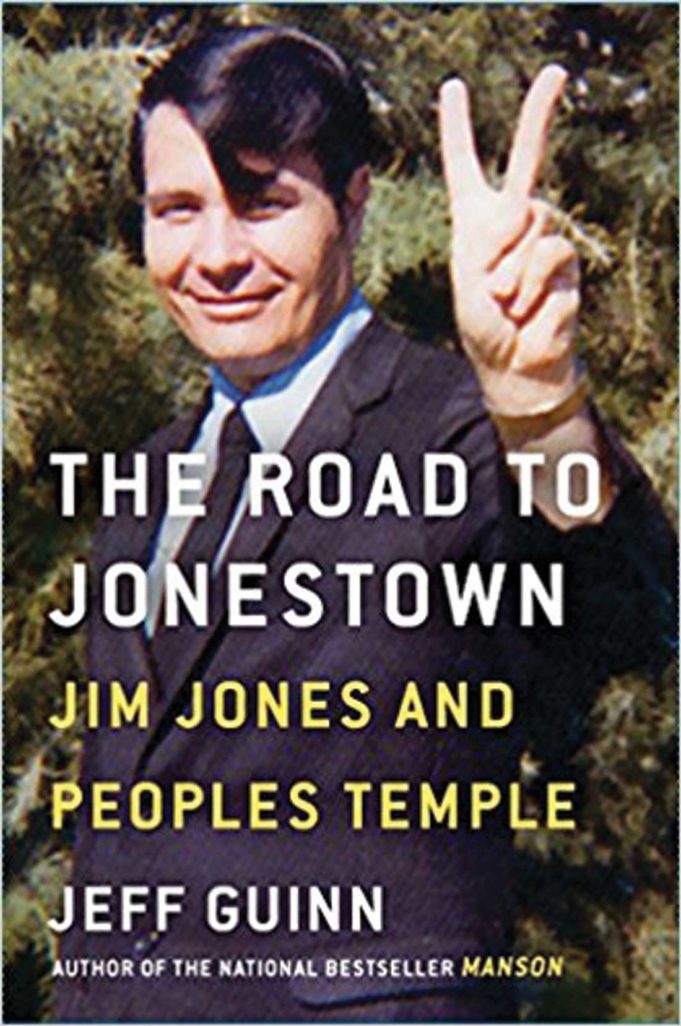

In Guinn’s latest book, The Road to Jonestown, the author focuses on Jim Jones, the reverend from Indiana who led his Peoples Temple (Guinn notes that to discourage any senses of personal ownership, Jones excised the apostrophe from the name) to their deaths in a Guyana jungle. The book is much more than the well-trodden story of blind faith run amuck. Guinn masterfully combines unparalleled document research and interviews with those left behind to understand how a man of God could go from minister to maniac, how people could go from congregants to victims, and how ideals move from beneficial to dangerous.

Jones’ life reads like two different biographies stitched together. In the first half, he comes off as a kind of evangelical heavy hitter, a Billy Graham or Joel Osteen. Jones was the son of a wounded World War I veteran and an eccentric woman who swore and smoked in public to shock her neighbors. From a young age, Jones wanted to be a minister, and Guinn foreshadows what kind of minister in a formative lesson from Jones’ mother: “There was always some Them out to get you, and reality was whatever you believed.” (Guinn’s italics.)

Despite his mother’s lesson and youthful admiration of Hitler – major red flags in hindsight – Jones rose to religious prominence through a practical social justice message. The young reverend would do the unthinkable in Indiana at that time by reaching out to and fighting for African Americans. In the Temple’s early days, it was called “Community Unity,” and the congregation met in a small storefront. One Sunday, Jones asked them “What’s bothering you?” An elderly black woman raised her hand and said she had a problem with her electricity. Though she had complained multiple times to her electric company, the problem persisted. And she was still getting billed. Jones penned a letter and had the entire congregation sign it. “This show of unity,” Guinn writes, “proved they were a real family in this church. They worked together to help each other.”

The letter worked, and at the next service, the woman announced that the company had sent someone to fix her electricity.

Jones’ status as social warrior would eventually give way to ever-increasing paranoia and more ridiculous spectacles like removing cancers, healing the sick, and not denying – albeit not directly encouraging – being deified by his congregants. Except the “cancers” were actually rotting chicken innards, the sick were accomplices planted in the audience, and Jones, as it turned out, was a mortal. The good of Jones’ mission, apparently, justified the lies. “Yes, there would be trickery,” Guinn writes. “But [his] accomplices believed that Jim was simply doing what was necessary for the continued survival of Peoples Temple.”

Jones and the Temple did indeed do good work before escaping troubles in the United States to settle a doomed commune in the Guyana jungle. The years of the good, the ethically dubious, the ever-increasing paranoia, and delusions of grandeur swirled into a poison that corroded his mind, Guinn writes.

The second half of The Road to Jonestown reads more like the biography of those quasi-religious demagogues whose madness would propel their groups to violence – Charles Manson and Shoko Asahara spring to mind. All of the good works and working together eventually devolved into Jones telling a Temple official, “Keep them poor and keep them tired, and they’ll never leave.” Many never would.

Since the discovery of the dead in 1978, many have tried to explain Jim Jones, Peoples Temple, and the mass suicide. The breadth of Guinn’s research and depth of his interviews contextualize, personalize, and analyze the Peoples Temple in a whole new way, for a whole new generation. Here is where Guinn soars. No person is too minutely involved not to be interviewed. No document is too mundane not to be cited. No contemporary news article is too small to be ignored. He spoke to the Temple’s surviving higher ups and regular Temple goers, Jones’ surviving children, early detractors, family members who fought to rescue their loved ones both at home and abroad, and government officials from the United States and Guyana.

Through elegant, nonjudgmental prose, Guinn synthesizes the facts through personal stories of those who survived, those who lost, and those who failed to stop it. He writes so compellingly that the reader, fully aware of what lies at the end of this road, has no choice but to complete the journey. It’s like watching a horror movie, wanting to call out and warn the doomed of the monster in their midst. The reader can do nothing as nearly 1,000 Americans line up to drink poisoned Flavor Aid at the behest of a reverend from Indiana.

The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple

By Jeff Guinn

Simon & Schuster

531 pps.

$28