Mornings at Diana’s Club have taken a serious tone lately. When I dropped by the small health-food store on the North Side not too long ago, the regulars were still discussing politics. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has become a recurring theme ever since President Donald Trump ended the program last fall. Despite strong public support for DACA, Congress has yet to agree on a plan to save it.

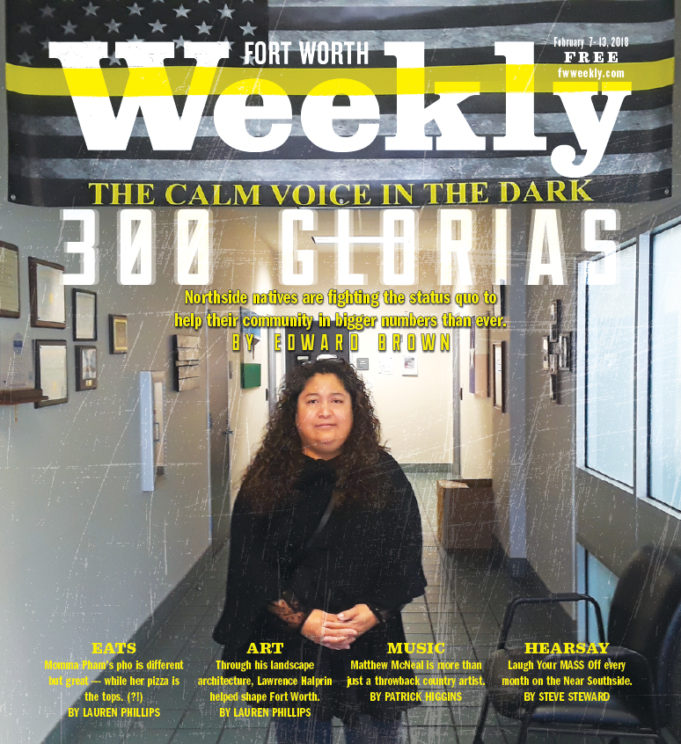

Lifelong Northside resident and grassroots organizer Gloria Garcia attends most of these meetings that began several years ago. Some days, the 45-year-old mother helps non-English-speaking locals translate documents. More often, she connects concerned parents with the proper public official or lawyer who can answer immigration-related questions. I met two brothers that morning, Robert and Steven Narvaez. Their uncle, Louis Zapata, became the first Hispanic Fort Worth city councilmember in 1977, a position he held for 14 years.

“A lot of people are afraid to drive,” Robert told me, referring to a perception held by many in the Hispanic community that peace officers unfairly target Latinos. Like Gloria, Steven helps to translate letters and documents that are brought to the meetings.

Photo by Edward Brown.

A few days earlier, I met Garcia at a Fort Worth police department 911 call station. As part of her volunteer efforts with the crime-watching group Code Blue, she regularly does ride-alongs with patrols or volunteers at call centers. The mother of three became civically engaged after her husband, an undocumented worker from Mexico, was deported several years ago without what she said was due process. More recently, she has become politically active, registering voters and confronting what she said is a Northside political establishment that is often combative toward those working outside its circle of influence.

Garcia is part of a growing number of parents and activists who are using grassroots organizing to uplift an underdeveloped and historically rich part of Fort Worth that they have called home her whole life.

Growing up on the North Side in the late 1970s gave Garcia a firsthand view of the forces that shape it today. When her family moved to the Diamond Hill neighborhood in 1978, her neighbors were mostly white and middle class. Over the next two decades, the residents who had long called the North Side home moved or died. They were replaced mostly by people lower on the socio-economic scale. In the midst of that change, Garcia became a single mother at the age of 27.

“Safety became an issue,” she recalled. “There were areas around me that were becoming crime- and drug-infested. I couldn’t move. I didn’t want to move. I realized that all I could do was try to make things better.”

That’s when she started knocking on doors, she said, referring to early attempts to petition the city to install speed bumps nearby and to encourage her neighbors to participate in National Night Out, an annual community-building event.

“I believe it’s my personality,” she said. “Growing up, I was really lucky that my teachers told me, ‘You’re going to have to bring out what you have inside, because you’re going places. There’s a plan for you.’ Honestly, they made me feel like I could do anything. I guess I started believing it.”

Some early attempts failed, including her request for speed bumps. Fort Worth city officials are generally reluctant to install the speed-controlling measure, citing lowered emergency response times and higher maintenance costs.

In 1996, Garcia found a new avenue to support her community while working as a notary for a private business. People were always asking her to translate financial documents from English to Spanish and vice-versa. Since then, she said, translating has become her passion. She frequently translates for Spanish-speaking individuals at Fort Worth school district meetings and in civil court cases.

In 2003, Garcia married her current husband, Jose. As her three children grew, they began attending community events and school meetings with their mother. Garcia often volunteered but did not become politically active until 2008, when her husband of five years was abruptly deported to Mexico while on a work trip.

Jose was working for a roofing company when a Mineral Wells police officer pulled over the car Jose was riding in as a passenger. Garcia believes the vehicle was targeted because its occupants were Hispanic. She began documenting what she said were lapses in due process under federal immigration law.

“They didn’t let him talk to his lawyer,” she said. “They didn’t let him make a phone call. When Jose’s friends went to the jail, [the Mineral Wells police department] told them he wasn’t there.”

One day after his arrest, Garcia was informed that her husband had been deported to Mexico. The mother of three soon stumbled upon a newspaper article that directed her to Maria Robles, coordinator for the Arlington branch of Proyecto Unido, a human rights committee supported by two nonprofits: Border Network for Human Rights (BNHR) and Reform Immigration for Texas Alliance (RITA). Robles is now the bilingual organizer for the racial justice nonprofit Faith in Texas.

Fighting away tears, Garcia told Robles about her situation.

“My family was destroyed at that point,” Garcia recalled. “My girls were little and needed their dad. It took Maria’s strong words and guidance to begin turning things around.”

Robles said it often takes a tragedy for U.S. citizens to realize how much influence they can have. Robles told the bereaved wife that she needed to become politically active and to begin meeting with local politicians. That advice, Garcia said, created a “household of advocates.”

With the help of Robles, Garcia began volunteering for BNHR. The El Paso-based immigration advocacy group, following Garcia’s and Robles’ requests, began sending staffers to train grassroots organizers in Fort Worth and the rest of North Texas.

“Gloria and I took training around human rights and constitutional rights,” Robles said. “Even people who are undocumented have the protection of the Constitution. They need to know when and how to utilize that, especially the right to remain silent.”

BNHR staffers encourage advocates to become involved in local politics by taking on low-level, volunteer positions with the city and county. Garcia said she is currently a deputy registrar, precinct chair, and election judge with Tarrant County.

“I want to know and learn the system, mainly because I’m able to answer questions now,” she said. “I’m not getting info from a third party. I’m able to answer because I was there.”

In late 2009, Jose was reunited with Gloria and his three daughters and has remained here ever since.

Building off her grassroots training, Garcia remained focused on local public schools. One of her early successes was bringing M.H. Moore Elementary School its first parent-teacher association six years ago.

“The schools were falling short when it came to providing PTAs, carnivals, and parent engagement,” she said. “A lot of the children there were first-generation Americans. I told the parents that they have to be active. A lot of the parents felt they were not getting support” from the school district.

Former Fort Worth school district superintendent Walter Dansby arranged to meet with the parents.

“We explained our challenges,” Garcia recalled. “We told him how we were washing pans out of a small sink. He had [school district workers] paint several rooms, add new lighting, and install cabinets and sinks [at our school]. It was amazing.”

More recently, Garcia has become frustrated with Fort Worth school district leadership. Initially, she said, she put a lot of faith in school district board member and former board president Jacinto Ramos, who represents her district.

“He seemed nice at first,” she recalled. “Now that I know him, he gives the same political [pitch] he told me the day I met him.”

Ramos and several Northside politicians are more interested in photo opportunities than returning her phone calls, she said. Over the past few years, she said, Diamond Hill-Jarvis High School has lost several college-preparatory courses, including a veterinary program.

I reached out to Ramos for a response but did not hear back in time for this story.

“They only work with their circle of friends,” she said. “These people start getting put on boards and invited to social events, but we’re not seeing change in the community. This area has lost a lot.”

Garcia isn’t without her critics. One longtime resident who asked not to be named for fear of political retribution told me that Garcia’s online rhetoric can be highly partisan and divisive. A cursory glance at Garcia’s Facebook page found recent statements like “the dirty dozen are lying again” and “follow the political propaganda, dirty politics, and money.” Garcia makes no secret of the fact that she has volunteered for former city councilmember candidate Steve Thornton, whose unsuccessful 2015 run against former councilmember Sal Espino was both closely contested and characterized by accusations of dirty campaign tactics from both Thornton’s and Espino’s respective camps. Indeed, Garcia’s support for Thornton (who was running against Precinct 5 Justice of the Peace Sergio De Leon until last week, when Thornton withdrew due to a missed elections filing deadline) puts her squarely in the political arena. For her part, Garcia said she is simply looking to effect political change. I also reached out to Judge De Leon for this story but did not hear back.

Garcia is far from alone in her efforts to make her community more prosperous and inclusive. I also met with Leo Saenz, band member with the popular Tejano band Latin Express and a lifelong resident of the North Side. As we chatted over lunch, Saenz told me about his volunteerism in the community, which includes visits to public schools where he talks to students about the perils of racial conflict. After decades of progress, Saenz sees the current political climate as hostile to racial diversity.

“I would like to see more outreach on both sides,” he said, referring to needed channels of communication between minorities and whites. Last summer, Saenz said, a truckload of white males who called him a “fucking wetback” accosted him in his own neighborhood.

Incidents of racial hatred are on the rise, he said, because of Trump’s divisive rhetoric and SB 4, which passed the Texas legislature last summer and which allows peace officers to ask for the immigration status of a person they lawfully detain.

Real change, he added, happens at the local, grassroots level. Saenz said he takes an active role in supporting candidates who represent his district, including city councilmember Carlos Flores and Ramos. While he disagrees with Garcia over the effectiveness of elected officials currently working in the area, he agrees with her that political elections in the North Side tend to end with online insults and personal attacks from both sides.

“I hate it. Enough with the mudslinging,” Saenz said, noticeably frustrated. “Let’s roll our sleeves up and help each other out. We need to put our minds together for a solution.”

Economic development is important, he said, but jobs don’t matter when Northside residents live in fear of raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The recent decision by five city councilmembers to not join an ongoing lawsuit against SB 4 highlights the need for Fort Worth residents to get involved on a local level, Saenz said. There is a vibrant grassroots effort growing on the North Side, he said.

“Believe me, in the next election, [Fort Worth elected officials] are going to realize what’s up,” he said. “There’s a sleeping giant that hasn’t been awakened yet. There are a lot of people who are not happy.”

The neighborhood surrounding Steve Thornton’s 1910 home is a microcosm of the broader Northside community. All Saints Episcopal Church, home to a few hundred local parishioners, lies within view. Farther east are a hodgepodge of Tex-Mex restaurants, bars, law offices, and car repair shops. The largely service-based companies, which line either side of bustling North Main Street, maintain their storefront facades well enough.

Thornton greeted me, phone in hand, as I entered his recently renovated and spacious abode. He gestured directions to a visiting handyman before finishing the call and chatting with me. But first, he wanted to go for a walk.

His two brothers, Phil and Mark Thornton, were remodeling a home across the street. Within the past few years, Thornton has purchased a handful of houses nearby that he plans to either give to family members or rent out. A few of the residences in his neighborhood appeared neglected: chipped paint, overgrown grass, rotting wood. Thornton addressed what I was thinking.

Some of the shadier-looking homes are used to sell drugs, he conceded. Fort Worth police, he added, are aware of the problem.

Smoke billowed out the driver’s side window of a nearby truck. As Thornton walked up to the parked vehicle, the driver got the message and left. The predominantly Hispanic neighborhood, with its mix of young and old residents, reminds Thornton of his childhood years growing up in San Antonio, he said. It was his grandmother, born in Saltillo, Mexico, who first taught him the classism and ethnic bias of her homeland. Those lines, he learned, are based on ancestry (Spanish, European, Native American, and African-American) and whether you were born north or south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“There’s a subtle self-segregation” in this community too, he said.

Local politicians, he said, have used sectarianism to divide the Northside community for decades. During his two unsuccessful city council bids in 2015 and 2017, Thornton said his opponents – first former city councilmember Sal Espino, then city councilmember Carlos Flores – called his Hispanic heritage into question. Thornton, who speaks fluent Spanish and has a light complexion, said the attacks were “pure racism.”

Flores told me in a phone interview that Thornton’s accusations are “completely unfounded.”

“I ran my campaign based on the issues,” Flores said. “If Mr. Thornton feels he heard these things, it had nothing to do with my campaign.”

The two former political foes do share a concern over one thing: Hispanic voter turnout.

“As a group, we have low voter turnout,” Thornton said, referring to historically low voter participation within the Latino community. “That’s a reality because of the type of politics we have. We need to restore ethical politics so people aren’t apathetic. It takes people like Gloria. People say, ‘Oh, she’s always upset.’ People don’t want to be reminded that something bad is there. She’s not crying wolf. No. The wolf is there. The wolf is in office. Now that he’s there, he’s becoming a more formidable presence.”

Divisive politics on the North Side protect the status quo for politicians and wealthy families who benefit from city resources going toward downtown Fort Worth and the West 7th area, he said.

Mayor Betsy Price “needs to get her initiatives done,” he continued. “She is answering to big money. In order to do that, she has to have five votes on that council. She can’t allow someone like me in. Why would someone spend [hundreds of thousands of dollars] for a city council position that earns $25,000 a year? Why are we sustaining a system that’s corrupt?”

Thornton painted a stark picture. Toward the end of our interview, he highlighted what he said is a solution.

“Gloria, everybody, we all need to educate the public,” he said. “We need to knock on doors and show campaign contribution forms. ‘Look, here’s Steve’s campaign contributions. Here’s Carlos’.’ We need 300 Glorias.”

Fort Worth’s District 2, which encompasses the North Side, is on the cusp of an economic boon, Flores told me. He sees growth as key to weaning the area off service-based jobs.

“There are a lot of things coming our way that are going to make a big impact,” he said.

In addition to the Panther Island District, associated with the near $1 billion Trinity River Vision project, Flores ticked off Tex-Rail (an under-construction 27-mile commuter rail line that will extend from downtown Fort Worth to DFW International Airport) and the new development in the Stockyards. He also mentioned that Fort Worth is a finalist for a new headquarters for the tech giant Amazon (though there’s some ambiguity about Fort Worth’s place on Amazon’s list).

“Those will bring in professional jobs beyond the service industry,” Flores said. “This is a unique time that we’re in, not just for the city of Fort Worth but in particular for District 2.”

Flores acknowledges that for his district to flourish, economic development needs to coincide with greater voter turnout among Hispanics and continued efforts to address controversial law enforcement policies, like SB 4 and 287(g), that disproportionately target the Latino community.

Many civic leaders see the controversial laws as co-opting local police into immigration enforcement. Tarrant County recently became the largest county in Texas to partner directly with ICE through the 287(g) agreement, which allows ICE agents to directly train county sheriffs on interrogation tactics and other immigration-related duties.

“I was the councilmember who authored the proposal to put SB 4 to a vote,” he said, referring to a failed effort to add Fort Worth to a large list of Texas cities currently fighting SB 4 in court. “Where the council disagreed was whether to join the litigation.”

Flores said he remains in close contact with the Fort Worth police department to ensure no officers “infringe” on any individual’s rights. The best way to address SB 4, he said, is for locals to contact their state-level officials.

Flores rebukes Garcia’s notion that publicly elected officials representing the North Side are divisive and focused on photo opportunities.

“Divisive? I would counter that,” he said. “The elected officials representing the North Side, Diamond Hill-Jarvis, and Greater Northside Historical areas have for many years volunteered in their communities and are actively involved. Look at the composition of the boards and commissions that serve District 2. These folks want to serve their community.”

Robles said that thanks to individuals like Garcia and nonprofits like BNHR there has been increased interest in grassroots community organizing.

“We are starting to see students [at the University of Texas-Arlington] interested in participating,” she said. “I think [the interest] has always been there,” but recent legislation like SB 4 has galvanized the volunteer effort.

“People are realizing that the time for change is now,” she said. “Gloria is a prime example of someone who took a tragedy and turned it into something positive for the community. Now, she is the voice of the voiceless.”

Saenz noted that divisiveness has characterized politics in the North Side for as long as he can remember. He doesn’t see that changing anytime soon.

“Everybody has their camps and their ways of thinking,” he said. “Now, there is continual bickering. How can we possibly move forward?”

After our interview, I drove Saenz home. His wife had already left with the family van (custom painted with a Texas flag theme). As we headed east along Jacksboro Highway, Saenz pointed toward nearby local schools and businesses. Despite the political bickering, he remains hopeful for his community. Northside public schools have the most dedicated principals he’s seen in decades, he said.

“We all want a good education for our kids,” he said. “We want things for our kids that we didn’t have. We have to push for that. We have to set aside differences and understand that we’re working toward the same values.” l

Didn’t 300 Pound Gloria just join code blue? She has worked campaigns, she is a republican operative that is paid under the table to lie, harass, bully and cause chaos in local democratic elections. As a matter of fact she was about to be removed as democratic chair when it was found out she was a turncoat. She has been expelled out of several community groups due to her chaotic personality. If you actually spent time in NS DH and met with residents you would learn that this is a false narrative, nothing new when it comes to Gloria. Several groups could speak on what this turncoat has actually done for the community(not a single thing) The Mariachi Moms, DH High School PTA, staff at NS High to name a few. Where I come from we don’t listen to the words of those paid by the enemy to disrupt the progress of the community. This lady works with the enemy bought and paid for to help hold down her own race, she once wrote a damaging letter about a Hispanic Female who was being recognized by her peers in the Hispanic Community for Actual Factual Work done in the community. This letter was so vile and only served a purpose to inflict damage out of jealousy over the respect given to an up and coming Hispanic Leader in the DH community. This act combined with her constant lies and the information found out that Gloria and family work with enemy’s of the community was reason enough for true Hispanic Leaders to not work with Gloria.

Then you interviewed Steve Thornton who claims to be discriminated against?! I thought he was supposed to be Hispanic? I never met a Hispanic person that could be Anglo and Hispanic depending on the day and crowd. So you have been discriminated against due to the fact that you used someone who lacked basic intelligence to date paper work on something so important? Failure to comply with election rules and regulations is that reason for removal of Thornton from the democratic ballot. Thornton ran twice for public office and twice the community said No, that sounds like voters being heard at the bollot box. Also why would Thornton try to fool voters by pretending to be a democrat (not suppressed he pretends to be Hispanic on occasion)? Have you read his fb posts? This clown learned the word Apathetic and uses it like a child that learns their 1st word. Let’s try a new word Thornton PATHETIC just like your sad attempt to fool voters. We all know who is actually responsible for trying to fool voters and it’s the two chimpanzees mentioned in this article.

Can the Hispanic Community get someone who actually knows the culture and truth about the community to cover our story’s instead of a hipster craft beer drinking Anglo who is great at researching and covering Anglo activity Blogs yet failed miserably at touching Hispanic issues. Can we get someone who is not in the pocket of the bearded lady/martinhoise group that uses this easy influential youngster that is in the Pocket of Paz and that Klan? This young man will leap at the chance do Paz or Kim’s bidding or the grand swaper Harris. Come on FW Weekly do you have any Hispanic writers, bloggers or interns that could not be afraid to step foot in Hispanic community’s to report the truth?

Your personal grievances with two individuals mentioned in the story do not detract from this article. I stand by everything reported here.

To bad someone gave birth to you, you obviously should have been vacummed out

I guess Stephen Glass,oops! I mean Eddie Brown is not a fan of being called out for not doing the actual research a journalist is responsible for doing in order to ethically write a paper or he just likes to making up things with his friends.

What type of craft beer is served at Aaron Harris or Alex Kim’s house Eddie? I can see you and Paz holding hands chanting build a wall, while Thornton fakes his Mexican accent and practices speaches using cartoons based on Mexican culture and pouring bush beans in a pan to warm up. Stick to craft beer and Art Tooth issues let an actual journalist preferably a Hispanic one with some ethics and ability to properly research cover important issues so you can stop helping separate an already oppressed people.

I grew up on the same neighborhood Steve Thornton is living now. I agree with what Steve Thornton is saying. I’ve meet Sal Espino and he always seemed like an opportunist.

why Is this guy Brown always making up things? He has never done a truthful account of anything that actually happens. I have to wonder how hard it must be to write for this paper after reading any of this dingalings articles. How many mushroom stamps did Thornton give you to write this bs?