As most former American Lit grad students around the country can tell you, it’s tough to shake the requisite terminology, phrasing, and general concepts that characterized the academic paper chases of one’s youth. Voices (in perfect English, of course) still echo and frame one’s perspective, and the emanations that have most reverberated through my mind over the last decade come from American literary critic Leslie Fiedler — especially after I read a Joe R. Lansdale book.

In Love and Death in the American Novel (1960), Fiedler argued that the primary theme of American literature was white male protagonists fleeing to a frontier or wilderness with male companions of color to escape Puritanism and marital domestication. He noted that this overarching narrative was conveyed by hardy methods of male bonding, ranging from those of a prepubescent nature, as in the relationship between Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to that of the adult, quasi-homoerotic friendship of Ismael and Queequeg in Moby Dick. In “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!” — a literary lightning strike published in the Partisan Review in 1948 — Fiedler claimed that white male flight with men of color was an attempt to assuage white male guilt over the crimes whites had committed against persons of color and indigenous peoples throughout American history, but he concluded that it would never absolve them: “Behind the white American’s nightmare that someday, no longer tourist, inheritor, or liberator, he will be rejected, refused, he dreams of his acceptance at the breast he has most utterly offended.”

Fiedler called white America’s dream of forgiveness “sentimental” and “outrageous” but suggested it was the only game in town and that “we play out” this “impossible mythos” generation after generation, futilely hoping to achieve some kind of redemption.

Eminent American literary critic meet Texas champion mojo storyteller.

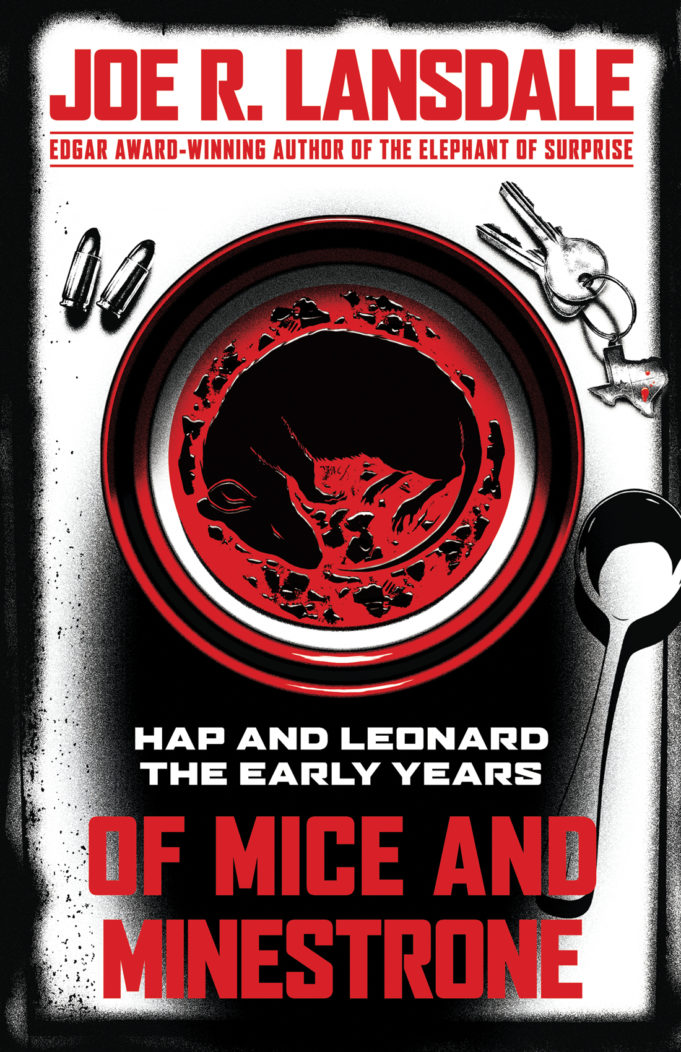

The 2020 release of Lansdale’s Of Mice and Minestrone marks 30 years of the author’s two most popular characters, Hap Collins and Leonard Pine, and if you’ve been following this East Texas duo as long as Lansdale fans have, this episodic prequel is manna from redneck heaven — especially if your idea of rednecks includes a liberal white man and a gay, Republican black man — both of whom are backwoods brawlers to boot.

From the beginning, Hap and Leonard were fraternal outliers, incessantly vexing to devotees of traditional Texas stereotypes but so authentically Texan that they couldn’t be ignored.

Hap finds brotherhood with Leonard, but there are no teases of homoeroticism in their relationship because Leonard is proudly and openly gay and Hap is unshakably if not happily heterosexual. Their friendship transcends race and sexuality, and the dynamic of their piney woods escapades challenges Fiedler’s claim. Hap and Leonard exist as equals in spite of their country’s cultural baggage. Lansdale’s writing in the series also makes short work of a standard white peccadillo commonly featured in the mixed-buddy plots Fiedler alludes to. In The Last of the Mohicans, Moby Dick, and even on up to The Lone Ranger and One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the male characters of color are almost invariably secondary to their white counterparts. But Hap and Leonard thrive with equal measure in Lansdale’s fiction, and this tilts Fiedler’s paradigm on its ear. Though the book series is told mostly from Hap’s perspective, Leonard’s story is explored unabashedly, and he and Hap rage against homophobia, sexism, racism, bigotry, and religious dogma with bare-knuckled ferocity. The Texas that Hap and Leonard navigate with their wits and fists is not post-racial, but Hap and Leonard are, and Lansdale explores this evolution as entertainingly as any American writer ever has. Hap and Leonard take love and adventure where they find it and right wrongs when they can. They’re like a Texas version of the Dukes of Hazzard, if Hazzard County was in East Texas and the “Dukes” were smarter, tougher, and meaner and rip-roaringly woke.

Hap and Leonard began their 20-plus volume journey in Savage Season (1990). It continues this May in Of Mice and Minestrone (Tachyon Publications), in which the reader is given some of their backstory, like what happened before Leonard went off to the Vietnam War and Hap was imprisoned for refusing to do so.

Of Mice and Minestrone is enthralling storytelling that engages readers with dashes of simple wisdom and hard truth. And this particular volume includes a quirky, culinary epilogue from Joe’s daughter Casey.

Violence aside, Hap and Leonard keep trucking on the correct side of history and humanity, and Lansdale’s storytelling is thrilling as always.

Of Mice and Minestrone,

by Joe R. Lansdale

Tachyon Publications

240 pps.

$8.69-15.95

Okay, okay, I get it that you college-educated rod strokers gotta turn good ol’ pulp fiction into some big psychological deal, but we read the stuff ’cause it’s fun. It’s alcohol, violence, sex and survival in a world where most of us are confined to cubicles performing meaningless tasks. Just read it, don’t academize it. Joe Lansdale rocks!

Nice to see Joe Lansdale get some love. Some of his early ‘non’ Hap & Leonard stuff is fantastic!