“Stop Six will take you fast,” Derrick says as he slots a key into the front door of the one-bedroom apartment where he stays. “It’s sad. I seen good girls come over here, move in. They wasn’t drinking or nothing, not smoking weed, nothing. Next thing you know, they are sitting around, popping Four Lokos, running the streets. This place, it will take you.”

Derrick is a Day One, which is to say that he was born in Stop Six.

“Growing up here,” he says, “you see people selling dope, doing dope. You see it all. People die over here. Fights, you know. So you get caught up in the mix. You want to be a part of it. You want to be ’hood. The devil be roaming around here, you hear me? Out here, the devil will pull up before God will.”

Derrick turns the key, the metal bolt snaps back a little too loudly, and he elbows the door open.

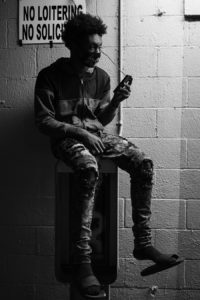

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Two steps, and he is across the tiny living room and into the kitchen. He fiddles with a few knobs on the front of an old oven, gets a spark, and lights a Newport off the front burner.

I unpack my lighting gear quickly. People are already starting to gather in the dim twilight beyond the open door. Word has gotten around. Some photographer is taking pictures. Derrick greets some of the visitors by casually dispensing up-close half-hugs and back slaps, while others, those from The Bricks, receive special, impossibly intricate, coded handshakes.

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

A little more than four square miles in total size, Stop Six is a complex place, one where the street you grew up on matters. There is a kind of geographically based caste system at work here. Sure, anyone can be a Blood, but only a select few, by accident of birth and family address, can be a Truman Street Blood. Derrick isn’t a Truman Street Blood, but he is from The Bricks, the projects, specifically the 4900 block. The Stop Six caste system is so atomized that even something as small as a block of the projects has its own handshake, culture, and history.

Patricia Benjamin, known throughout the neighborhood as Miss Pat, is the first to sit down. Flanked on either side by white-hot studio lights, she tugs on her wig and takes such a deep drag on her Newport that a solid two inches of cigarette is instantly turned into ash. She begins to talk as I snap away, telling me about watching her father abuse her mother, about how her mother took a knife to him one night, and about how their divorce left her confused and hurt.

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

“I just want somebody to love me,” Benjamin says. “They say they do, but they have a strange way of showing it. One minute, you cool with me. Next day, you don’t want to be bothered. Say bad things about me, things that hurt. Then you come back and say that you didn’t mean to say it. I don’t know what to believe.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Benjamin sucks on her cigarette until the filter begins to smolder and announces, “OK, that’s enough. No more tonight.”

The room has filled up fast. Benjamin has to do some pushing to get out of the front door.

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

As I watch her go, I think about something Derrick told me: “The struggle moves from generation to generation to generation. That struggle, it goes with you, and it leaves a bad mark.”

“I ended up over here by the grace of God,” Sheri Samuels tells me after I finish taking her picture. “I was homeless for two years, living in my truck. They tried to take my oldest son, Zay, but he wouldn’t go. He never left my side. I cried every night. I told my son to leave me, go with your friends, and he did. But that night, he was right back, telling me, ‘Mama, I’m not leaving you.’

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Samuels continues, “One day, my sister snuck me into her house. She snuck me in and closed the door, and all of a sudden, I just started crying because I knew I had to get back out to the truck [where we were staying] in that cold. I heard this voice say, ‘Stand still.’ The voice sounded so real and so loud. The next day, a letter came in the mail. I got my housing. Now, we got a roof over our heads.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Blessings and curses come mixed so close together in Stop Six that it is difficult to tell them apart. An abusive father is forced out, but the hurt lasts, causing pain that continues for decades. Any place where 40% of the population lives below the poverty line and the murder rate is 37% higher than the national average can feel cursed. Talk to any Stop Six resident long enough, and the conversation will always, without fail or exception, include the phrase “they were killed right over there.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.fStop

Sometimes “right over there” is the patch of gravel behind what was a red-painted liquor store that now stands abandoned, its windows boarded up and a “no trespassing” sign posted on the locked front door. A girl was found there, behind the red store, shot to death, lying in the gravel. “It was a long time ago,” Slim tells me as he looks into my camera. “I don’t remember her name anymore, but that’s where they found her.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Sometimes “right over there” is Village Creek Park, a small green space to the south of Stop Six where five people were injured on Mother’s Day by gunfire. “They are calling it the Mother’s Day Massacre,” says Zay, Sheri Samuels’ eldest son, the son who wouldn’t leave his mother’s side even when it meant sleeping in the cramped cab of a truck.

The blessing of Stop Six, though, is created by what that pressure, what that grind, what that struggle creates: resilience and community.

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

I began photographing Stop Six almost a year ago by documenting the closing down of the projects, and like so many of the people who came to Stop Six, I got caught up in the struggle. The pride that the people have in their community and their heritage is strong, as is their grief and pain at the violence that has torn so many of their families apart. It is this complex mixture of pride and pain that I have spent hundreds of hours endeavoring to capture.

Stop Six is changing. The Bricks are all but gone now, empty shells waiting to be bulldozed. In a matter of months, there will be no new project babies to teach the 4900-block handshake to. How much more about Stop Six will change? I wonder as I pack up my camera for the night.

“No matter where I go or how far away I am,” Derrick tells me as we break down my equipment, “my feet always bring me right back here. There’s good people here, working hard against that struggle.”

That, I know, will never change.

Please edit the story to give a little history behind the name “Stop Six” and the location. Also, a little more in depth history on the gangs. Caville Place is Blood territory, but go a little west to Poly and it is Crip territory. You are correct is stating that the gang sets vary by block.

How does a real community with history and pride get so depressed and hopeless?

I believe growing up in the stop 6 neighborhood is not what ppl make it to be. Yes, there are drugs and violence in every neighborhood. It’s a different story to this community. We are ppl of hope, looking for opportunity to a different way of life. Some of us were misled by the older generation OGs. If painting a pic for our community in a bad way don’t paint at all unless telling the story right. Me myself is a stop 6 Truman street Blood and I do try to make change for our younger generation. I’ve always stood on what was right.

We depressed and hopeless because ppl make us.

He slanted his article to make stop six look worse. That happens alot in the media. For example the “mothers day massacre ” at village creek park. That park is not located within the stop six neighborhood but an entirely different neighborhood with different gangs. Just Iike you mentioned Poly, a historic neighborhood west of stop six. Well, Eastwood borders Stop Six to the South. But sometimes they get labeled as stop six in media. Caville , a public housing projects at 4900 block of Rosedale st. Is being torn down. That has nothing to do with Truman St. or Village creek park. P.S. “Truman Drive” itself is actually a nice part of the neighborhood with a public park and and community center. But Blood members claim it as Truman Street regardless of the street they grew up on.

“Project babies…” really, Brimmer? Do better. Have more respect for the PEOPLE you are writing about. I can’t stand the white gaze.

This is so sad to read about the neighborhood I grew up in the 50s, 60s and 70s. This was not Stop Six in my day. Proud people working hard people that loved their neighbors. My grandfather was one to help establish this community even some of the surrounding communities were not bad areas. My children and nieces and nephews growing up in this area enjoying our schools, parks, events for adult’s and kids. We knew each other in a friendlier and respectful way not hurting and killing on another. Sure we had our cafe’s and house parties but it was not near violent as what I’m reading on this article. It had to be infiltration of people from other states that came here. Now maybe a few of our children’s children might be mixed in but not many. We had doctors lawyers, teachers, ministers and just hard working proud people that loved this community and kept it up well. People that don’t know the history of the Stop Six community need to go to the city archives and read on the establishment and building of Stop Six.

This place was a nightmare with broken dream and no promises no future no hope no way out its like a trap now I’m speaking of my times no one else I hated the place I’m glad they pushing it down need push down the whole Rosedale area even the School wasnt about nothing they didnt care about the children who attended there just teach them the basic reas write math but didnt teach us truth about history just like you still in slavery but you free to walk but in the 50 60 70 you couldn’t leave out that perimeter you wasn’t allow on Truman street it was all white neighborhood even Stallcup Ramey Ave Eastwood Poly mostly white all Stopsix is a trap with no end all the bad out weight any good what good !! Nightmare of bad dream all you hear was sad news only time you had good time when mom give you that special love when their were good memories it’s only family related nothing good about projects but I can say this much it wasn’t as bad as it is in 20 century in 90 it really went down hill seeing it torn down bring many joy to my heart back then you could leave your doors open sit on porch with no worries that was in the 60 70 80 after that went down hill change is good I hope it for the better in every neighborhood need peace and quite and love I say this it was a good place for those who needed it

This story could have been so much more! It. It could have included how the area got its name. I grew up there knowing that! It could have included the actual name of the area as well as the legacy of the street namesakes. I grew up there knowing about Amanda and others. I was proud to be a member of the community; to partake of the legacy left long ago by those who carved out solace for themselves and their progeny! I attended Cowan, Dunbar Elementary and Dunbar Middle. The teachers lived the stories that made up the area. So I tell my multifaceted stories as well.