In December, County Judge Glen Whitley swore in Dr. Kendall Crowns as Tarrant County’s new medical examiner (ME). With an annual salary of $425,000, Crowns oversees an ME office tasked with identifying the cause of death in homicide cases, unattended deaths, and other situations where the reasons for the demise are unknown. MEs often testify on behalf of the state in criminal court cases.

Crowns inherits an office that remains mired in controversy and accusations that the previous ME, Dr. Nizam Peerwani, gave false statements in court and oversaw an office that filed unreliable autopsy reports.

Last year, a group of criminal defense attorneys seeking justice called for an investigation into Peerwani’s “administration as the medical examiner.” Inaccurate reports by the ME’s team led to faulty evidence being admitted to court, the attorneys argued. Around that time, a district judge found that Peerwani had given false testimony in a 2006 murder case that sent one man to death row, where he remains to this day. An internal audit of the county medical examiner’s office in 2020 found 59 errors in 27 cases. Dr. Marc Krouse, the co-medical examiner at the time, was suspended in late 2020, and county leaders fired him not long afterward.

Shortly before retiring from Tarrant County, Peerwani began working for Lubbock County in October as an independent contractor. The ME agreement that ends Sep. 30, 2022, pays a fee of $350 per case.

As egregious as Peerwani’s team’s mistakes appear, one prominent government watchdog alleges that the true extent of Peerwani’s malfeasance has been hidden from the public by local county officials and members of the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office.

*****

Wherever David Fisher turns his attention, powerful public officials tend to lose their jobs or, at least, their credibility. By his own admission, Fisher has forced the removal of 10 chief medical officers in this state over the past 15 years. A cursory glance of online medical examiner stories shows a recurring theme of Fisher filing complaints or forwarding evidence that leads to terminations, blocked appointments, or investigations.

In 2013, Fisher blocked El Paso’s commissioners court from hiring Dr. Khalid Jaber, a non-U.S. citizen at the time, as chief medical examiner. Since Texas’ Code of Criminal Procedures states that medical examiners are judges who can order judicial inquests “with or without a jury,” Fisher made it known to the commissioners that hiring Jaber for a judicial position would violate state laws that bar noncitizens from acting as judges.

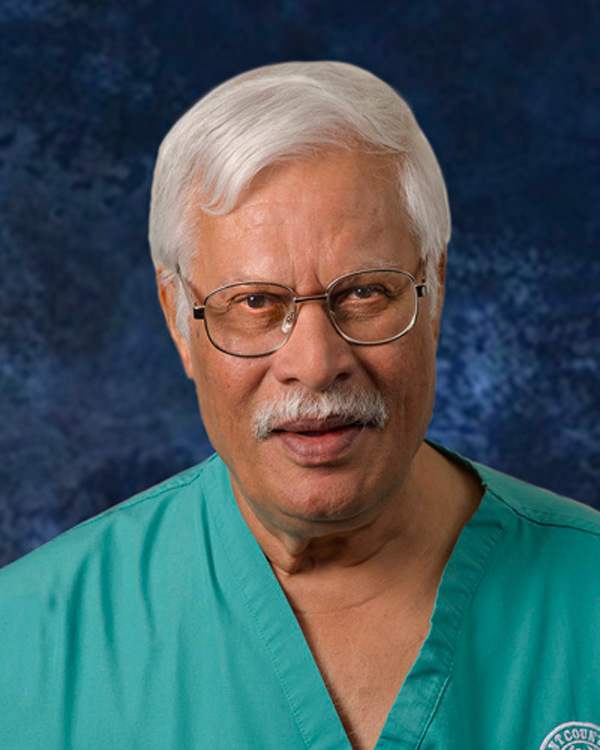

Fisher now spends much of his days focused on Tarrant County, an area of Texas characterized by powerful elected officials accustomed to ruling with impunity and bending — if not outright breaking — laws. In 2009, the Weekly reported on one of Fisher’s allegations against Peerwani, who is now 74 and who retired late last year after 42 years of service.

Fisher argued that Tarrant County leaders were paying Peerwani’s professional association — in this case, an incorporated business partnership — rather than an individual, which violates the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure that mandates all MEs to be an appointed “person.” Fisher has since spent considerable time collecting new evidence to bolster his case and to support a slew of new allegations against the former ME and the county.

In the years following our cover story, Tarrant County leaders continued to work with the professional association rather than the person until last year. County officials ignored my requests for comment on this and several other stories going back six months and counting.

In December, Fisher said he filed a complaint with the FBI alleging that Tarrant County leaders allowed Peerwani, who held a green card during his tenure as ME, according to the Texas Secretary of State’s office, to conduct county work illegally in return for 60% of the doctor’s profits. The alleged victims of the fraud include taxpayers of the counties that contracted with Tarrant County’s ME office and the defendants who were prosecuted or convicted using evidence from Peerwani over the past 40 years.

It’s a bold accusation and one that Fisher backs with documents, opinions from the State Attorney General’s office, and an almost photographic recall of case law and statutes that relate to judges and medical examiners in the State of Texas. Peerwani did not return my requests for comment.

In mid-1979, Peerwani told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that he was a British national but failed to disclose that, according to the Texas Medical Board’s website, he was born in Pakistan. In the story, it was reported that Peerwani would fill the county’s medical examiner position that was vacated when Dr. Feliks Gwozdz died of a heart attack. During the interview, the young Peerwani said he had been an assistant medical examiner for Tarrant County for the past two years, adding that he planned to begin applying for U.S. citizenship in 1981.

According to Peerwani’s curriculum vitae, he began working as deputy ME for the county in December 1976. The Texas Medical Board’s website shows that Peerwani’s Texas Medical License became effective on the first day of 1978, which may be seen as evidence that as an assistant ME the doctor performed autopsies without legally required licensure from late 1976 to the end of 1977. Under Texas’ penal code, practicing medicine without a license is a potential third-degree felony, and every day in violation of the law constitutes a new offense. Fisher believes that had the Texas Medical Board known that Peerwani was allegedly practicing medicine without a license, the governing board never would have given him a medical license in the first place.

Fisher believes Peerwani was able to obtain a green card only by falsely stating that he had not broken the terms of his student visa, which would have forbidden him from working in the United States. If Peerwani ever applies for U.S. citizenship, Fisher alleges, the application would again be based on fraudulent information.

The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently ruled that anyone who violates the terms of their visa cannot gain citizenship.

Peerwani and Krouse began contracting as co-medical examiners for the county in September 1979 under a contractor agreement that required the two doctors to pay their own rent and expenses from an initial annual stipend of $170,000 per year to be split between the two doctors.

In the years after, Krouse and Peerwani built a multimillion-dollar business that also served Denton, Johnson, Lubbock, and Parker counties. In return, based on county documents, Tarrant County earned 60% of autopsy fees while Peerwani’s professional association kept 40%. In early 2021, Peerwani’s professional association earned $90,424 (February), $154,542 (March), and $174,713 (April) from Tarrant County. Peerwani’s agreement with Lubbock County, based on county documents, afforded a 60% profit share with the remainder going to Tarrant County. Monthly payments to Peerwani’s professional association from that county range from $40,000 to $50,000, according to Lubbock County documents. Based on the recent figures, Fisher estimates that the ME was netting upwards of $3 million a year through his various county contracts toward the end of his career.

In the 1996 article “Tarrant County’s Mystery Pact; Officials in Dark about Medical Examiner’s Contract,” the Star-Telegram noted Peerwani’s $800,000 annual stipend at the time was paid to his professional association, not him as deemed by law. District Attorney staffers told the newspaper that Tarrant County ME salaries were not available for “public inspection.” Fisher alleges that the local DA office, which handles open records requests, worked to conceal a range of Peerwani-related documents because the DA is responsible for approving those very contracts.

In 2009, Peerwani, County Judge Glen Whitley, and a DA representative approved a five-year contract with Peerwani under the previously existing terms. Two months earlier, staffers at the Texas Secretary of State’s office revoked the charter for Peerwani’s professional association, according to documents from the Secretary of State’s office.

“The 2009 contract renewal with Peerwani’s professional association was void since the charter was revoked prior to the approval,” Fisher alleges. “This set off a chain-reaction voiding the next five years’ renewals.”

One year after the state secretary revoked Peerwani’s business partnership, Krouse testified as an expert witness in a Denton court. During the August 2010 proceeding, he stated under oath that he was not employed by Tarrant County but rather by a corporation owned by Peerwani.

When asked if Peerwani’s company was the appointed official, Krouse responded, “Yes.”

*****

Fisher alleges that the reason Tarrant County signed contracts with Peerwani’s professional association and not directly with the doctor as required by law was due to Peerwani’s immigration status. The use of government facilities and resources to support a private business — i.e., Peerwani’s professional association — is one of several legally precarious issues that Fisher said he described to the FBI.

By sending bodies to Peerwani and Krouse, Fisher said, counties and courts expected autopsies by a government entity. For more than 40 years, Fisher continues, they were unaware that they were dealing with a private company that contracted with the county. Peerwani was never hired as a government employee, Fisher believes, and his lack of citizenship status should have barred him from acting as medical examiner for the county.

Where some may see business as usual, Fisher sees a concerted political conspiracy that sent millions of public dollars to a private business owned by a noncitizen at the time who should never have held office. Any conviction that relied on Peerwani’s testimony and autopsy reports should be considered suspect, Fisher alleges, adding that successive DA administrations have known about the allegedly illegal county business dealings and done nothing.

“When you have a district attorney’s office that is as corrupt as yours has been, anyone” can get away with this kind of behavior, Fisher said.