Lots of local judges, here and maybe across the state, have been shitting their black robes since April. That’s when we started looking into double dipping on the taxpayers’ dime.

Here’s how it works. When judges retire, they can still preside over cases as “visiting retired judges,” but by taking a couple of oaths of office, these judges can no longer receive their retirement monies while on assignment. By ignoring these oaths, visiting retired judges can be paid while presiding over cases and earning their retirement, and it seems a lot of our supposed arbiters of justice are A-OK with pulling a fast one on us.

For the better part of this year, our magazine has focused on judicial misconduct at the county level, and it was only through that work and the help of an anonymous whistleblower that the statewide issues with Texas’ Chief Justice Nathan Hecht recently came to our attention.

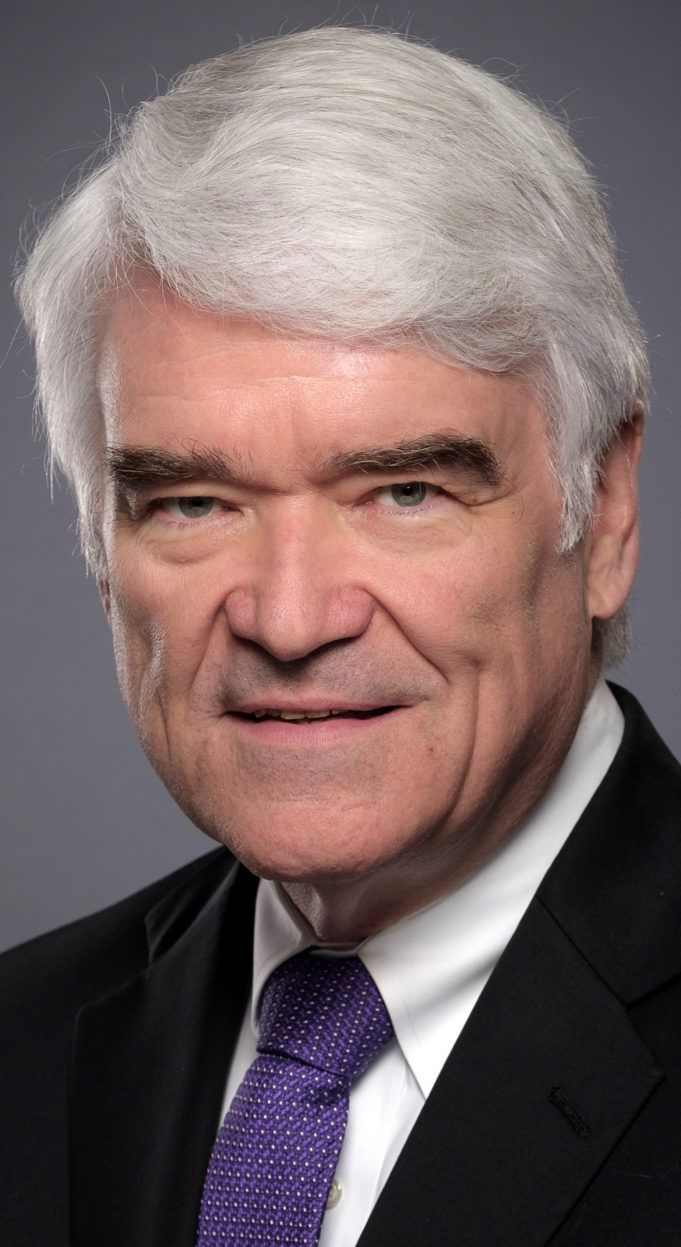

Hecht appears to have a fast and loose regard for the constitutional qualifications of retired judges like Sid Harle, whom Hecht regularly appoints to protect fellow powerful Republicans.

In mid-2017, Gov. Greg Abbott appointed retired judge Harle as presiding judge of the Fourth Administrative Judicial Region, which includes San Antonio. Soon after Abbott’s appointment, Hecht assigned Harle to a case in the Fifth Administrative Region, which includes southeast Texas.

“Pursuant to Section 74.049 and Section 74.057 of Texas Government Code, I assign you to the 28th Judicial District Court, Nueces County,” Hecht wrote on Nov. 3, 2017.

A review of the codes in question reveals that neither section allows the chief justice to assign a regional administrative judge to another region. Section 74.049 grants Hecht authority to assign visiting retired judges within an administrative region while the other cited government code allows Hecht to assign visiting retired judges to courts in other parts of the state.

As administrative judge, Harle earns $114,550 per year, according to the Texas Tribune. Visiting retired judges are paid on par with the daily rate of the judges they fill in for. When an administrative judge like Harle is assigned to a preside over a court and takes the bench, he holds a second office of profit under Article XVI, Sections 40 and 33, of the Texas Constitution.

Even more damning: Harle’s assignments by Hecht frequently led to the acquittal of powerful Republican officials.

One recent case involved Republican Judge Guy Williams, who was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon after pointing a gun at the occupants of another vehicle a year earlier. Harle presided over the March 2018 jury trial that acquitted Williams.

In mid-2018, again citing Sections 74.049 and Section 74.057, Hecht assigned Harle to the case of Republican Judge Dan Gattis in Williamson County. Gattis faced a Class A misdemeanor charge of official oppression for threatening a sheriff who was tweeting about internal county issues. With the consent of the sheriff, Harle later dismissed the charges.

Two years later, Hecht again assigned Harle to a criminal case tied to Williams. This time, Williams faced charges of making a terroristic threat, a third-degree felony, and criminal trespass, a Class B misdemeanor. The most recent reporting on the case indicates that Williams is seeking an acquittal for both charges.

Hecht’s September 2020 assignment of Harle to oversee a recusal hearing in Gillespie County, just west of Austin and a few hours’ drive from Harle’s San Antonio home court, shows how brazen judges act when protecting their own. That summer, someone named James McKinnon filed a lawsuit against Stephen Ables, presiding judge of the Sixth Administrative Judicial Region, alleging that Ables committed unspecified violations of the U.S. Constitution when performing public duties as a judge.

In response, Ables filed a successful motion to label McKinnon a vexatious litigant, a move that bars McKinnon from representing himself in any Texas court. For reasons not disclosed on court documents, 216th District Court Judge Albert Pattillo was asked to recuse himself from the case but refused to do so. Hecht assigned Harle to decide whether Pattillo could ethically rule over the matter that involved his colleague, Ables.

The following month, Patillo moved forward with the vexatious litigant hearing, suggesting that Harle did not order the recusal of Pattillo.

In his October ruling, Pattillo wrote that “courts cannot allow litigants to abuse the judicial system and harass their victims without consequences. This court orders James McKinnon to be a vexatious litigant.”

Pattillo’s use of the vexatious litigant law to silence dissent follows a pattern of Texas judges abusing the law to silence critics.

Austin-based attorney Mary Louise Serafine recently co-filed a civil lawsuit against several state leaders with the goal of overturning the law that recently banned McKinnon from ever filing suit in the Lone Star State. Judges often misuse the law to shut up defendants who allege judicial misconduct, Serafine told us. The civil suit, filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas in September, seeks to overturn the law on the grounds that vexatious litigant laws are an affront to norms of civil rights and due process under the U.S. Constitution.

“There is now a critical mass of people, myself included, who have now given up the idea that most of the courts — trial, appellate, and supreme court — operate fairly most of the time,” she said. “They don’t.”

This column reflects the opinions of the editorial board and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. He will gently edit it for factuality, concision, and clarity.

This story is part of City in Crisis, an ongoing series of reports on unethical behavior and worse by local public leaders, featuring original reporting.