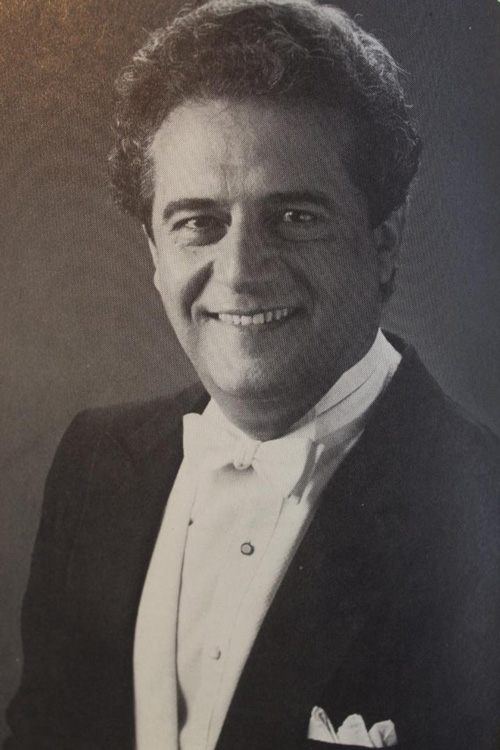

Reflecting on his 28-year career as music director of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra (FWSO), John Giordano mentioned how small the program was when he started in 1972.

“The budget for the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra was $80,000 a year,” he said. “We did four or five concerts a year. There was nobody making a living playing” for the FWSO at that time.

Though the city’s resident symphony orchestra did not have any full-time musicians, it did have one of the largest and most active volunteer support networks in the country: the Symphony League of Fort Worth.

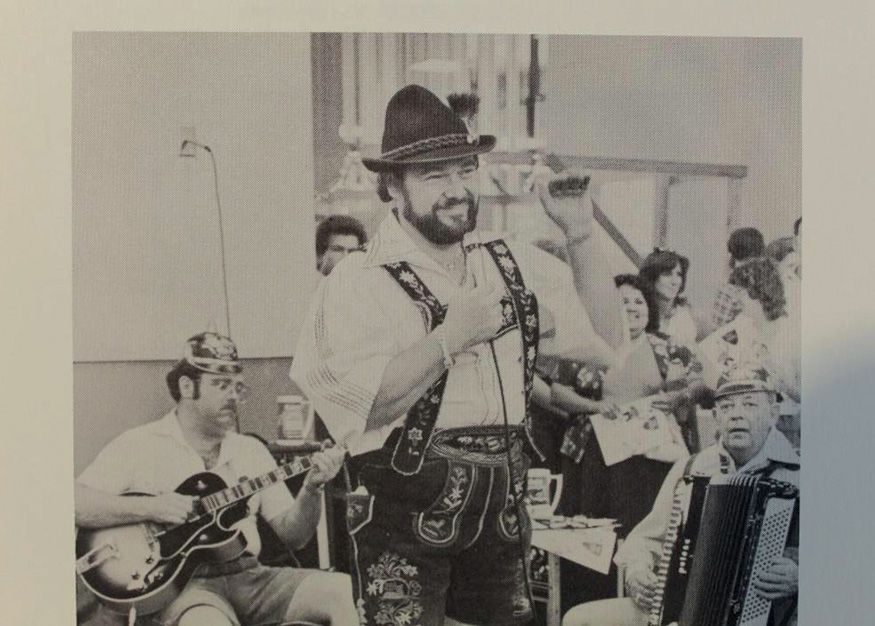

With hundreds of members who organized fundraisers like Oktoberfests and ticketed cooking classes, the league was more than a support group. It was the lifeline that allowed the FWSO to survive those lean years while slowly hiring full-time musicians.

“There would not be a Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra without the Symphony League,” Giordano said. “It was our main source of money.”

Courtesy Symphony League

Willa Dunleavy said one of the first things she did when she moved with her family to Fort Worth in the early 1970s was to seek out the local symphony league. Dunleavy, retired general director of the Fort Worth Youth Orchestra, said Fort Worth’s network of volunteers offered her the opportunity to connect with fellow music lovers.

Dotty Hall, the league’s current president, said the fundraising group’s responsibilities grew as Giordano slowly expanded the orchestra’s programs through the 1970s and ’80s.

“Once the orchestra started expanding, there was a greater need for money,” she said. “The league took care of the office. They answered phones and sold tickets at Monnig’s Department Store. They held cooking classes, fashion shows, and garage sales” to raise money for the orchestra.

From an all-time high in membership of around 500 in the 1980s to its current number of around 85, the league has remained a close partner of the FWSO. Hall said her group organizes four events per year to raise funds for and support the orchestra. Hospitality remains a major component of the group’s volunteer efforts.

“We go down to Bass Hall and offer the musicians coffee and pastries,” she said. “We try to show them how much we appreciate them. We have orchestra members from the finest music schools in the world. I think it is important to let them know how much we appreciate what they have done.”

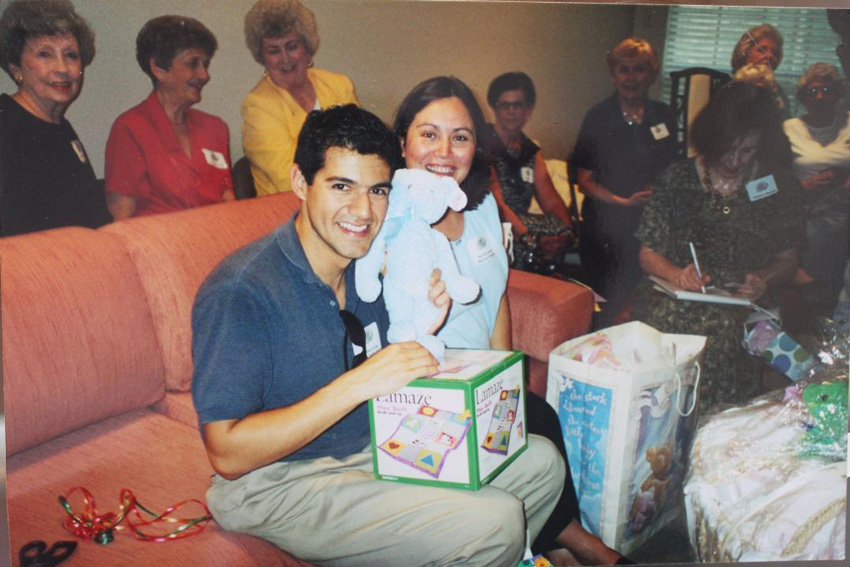

FWSO music director Miguel Harth-Bedoya, who stepped down from that role in 2020, said league members were among the first Fort Worthians to greet him and wife Maritza Caceres when they moved to Fort Worth from South America more than 20 years ago.

“My first impression [of the Symphony League] was their affinity for the musicians,” he said. “They loved being around musicians, and they knew the musicians by name and their family members and interests. Connecting with people is what music is about. Music lives through people, musicians, composers, and conductors. The value of what they do is priceless because you cannot buy peoples’ love and time.”

*****

The Symphony League’s founding in 1957 occurred the same year Robert Hull became music director of the FWSO and Robert Alexander was hired as the orchestra’s general director.

Alexander “immediately realized that a supporting organization of women volunteers was essential to the success of the orchestra,” reads one chapter of Connections and Serendipity, a 1986 book that documents the history of the FWSO. “From the beginning, the league’s major interest and financial support have been to bring music education to young people of ages 3 through high school, so they will grow to understand and appreciate good music.”

The volunteers used a wide range of methods to raise funds: garage sales, cooking schools, coloring books, and other moneymaking initiatives.

The group’s fundraising prowess grew with the formation of an annual Oktoberfest. The first German-themed festival took place at T&P Station, the downtown rail stop that is home to a craft beer tavern. For the inaugural festival in 1970, the building manager offered the space for $1. The Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce and Ben E. Keith, a food and beverage distributor, were early supporters of the ticketed event that featured performances by the Texas Boys Choir and polka groups, food, beer, and vendors. Around 7,000 people attended the event, helping raise $6,700.

Soon after moving to Fort Worth, Dunleavy became a lead organizer for the annual festival. By the mid- to late-1970s, the charitable event — which moved to the Will Rogers Memorial Center, then to its final home at the Fort Worth Convention Center — became a popular three-day fundraiser that eventually began generating $150,000 per year.

Courtesy Symphony League

Ray Landy, the longtime supporter of the FWSO and Fort Worth Youth Orchestra, “always ordered the big cheddar cheese wheel from Wisconsin,” Dunleavy recalled. “He would cut and sell it by the slice. [Former medical examiner] Feliks Gwozdz with his lederhosen and accordion would entertain with German folk music.”

It was a zoo, Dunleavy said with a laugh.

Gail Granek served as the league’s president when the group decided to cut Oktoberfest around 1999.

“The event almost became too huge,” Granek said.

Volunteers were “getting older,” she continued, “and the event required we haul everything, set up vendors, and organize performances.”

Granek said Oktoberfest was one of the only fundraisers for nonprofits when it started, but by the turn of the century, the city had dozens of similar opportunities competing for donors. By the time the league held its last German-themed fundraiser, the FWSO had cultivated a much more diverse group of donors and foundations for support.

During the early years of the Oktoberfests and with the financial cushion brought by Symphony League volunteers, Giordano set upon an ambitious plan to transform the FWSO into a professional ensemble on par with major orchestras across the United States.

“You cannot build a first-class symphony orchestra without [core members] rehearsing every day,” Giordano said. “The pay scale for the musician’s union was very low.”

Giordano approached the symphony’s board members and laid out a plan for increasing the number of concerts performed each year and hiring a core group of full-time musicians. Although the board offered no direct help, they approved the idea if Giordano could come up with the funding. Initially, he considered raising money for a 12-member chamber orchestra that could be augmented with union performers as needed. It was only after discussing his plans with famed concert pianist Rudolf Serkin that Giordano realized that he needed a larger team of full-time musicians to program the repertoire of the great classical and early Romantic-era composers.

“We hired two string quartets, one quintet, a brass ensemble, a woodwind ensemble,” and a percussionist, he said. “They played at almost every elementary school. The Symphony League was the one that went with them, introduced them, and was the moving force in helping. We didn’t have any staff.”

To fund the new ensembles, Giordano organized a retreat in Weatherford with the help of friend Martha Hyder, who served as chairperson of the board of the Van Cliburn Foundation. Rather than pitching the idea of underwriting much of the costs of the new FWSO hires, Giordano played to philanthropists’ desire to elevate the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition that launched just over a decade earlier in 1962.

Courtesy Facebook

“The Cliburn Foundation didn’t have much funding then either,” Giordano recalled. “We discussed what needed to be done to make the Cliburn a world-class organization” with several powerful people, including the Basses, Charles Tandy, and the Moncriefs. “They were [Hyder’s] friends.”

If the Cliburn was going to grow in prominence and attract the best pianists in the world, as Giordano and Hyder told the group, Fort Worth needed a world-class orchestra to perform piano concertos during the final rounds. The donors came through with commitments to fund the city’s resident orchestra, Giordano said, and the support from the wealthy benefactors led other established families to contribute to the FWSO’s annual budget.

In the decades since and as the two nonprofits began competing with each other for public funding, many supporters of the arts have forgotten that the Cliburn’s and FWSO’s current success was only possible through the generous help of financial backers who understood that Fort Worth needed both a thriving international piano competition and symphony orchestra, Giordano said.

*****

Michael Shih said Symphony League volunteers are often the first people prospective FWSO musicians meet during auditions.

“Members of the Symphony League provide snacks and drinks during audition day,” the FWSO concertmaster said. “It is a tremendous act of generosity that they provide. Not many orchestras have that. Auditions are long and stressful days.”

Beyond hosting hospitality luncheons, the volunteers often personalize gifts for special occasions.

“When our baby was born, I [performed at] an event for them this past year,” he said. “After I played, [Hall] got up and said, ‘Wait, don’t go anywhere.’ She brought out a baby gift for our baby. Every member of the league means so much to me and the orchestra.”

Shih said the orchestra musicians view themselves as a family and the audience as an extended family. The Symphony League reminds the performers that FWSO supporters care about the musicians as much as the concerts.

“I run into Symphony League members when I’m going about in town,” he said. “I’m so happy when we get a chance to chat. It gives me a chance to say thank you.”

Courtesy Facebook

Beyond providing financial support and the occasional luncheon, Symphony League members are active volunteers at FWSO educational outreach programs.

“So many serve as volunteers at our children’s concerts,” he added. “They are there as ushers to make sure children are in the right section of the hall. They do that not only for us but for the youth orchestra concerts.”

After the FWSO musician’s union went on strike in 2017 to prevent wage cuts — which ended following a $700,000 donation from an anonymous donor — Shih said the organization is stronger than ever.

“The board, staff, league, and musicians are working in concert with our incredible audience,” he said.

Hall said most Symphony League volunteers are well into their senior years. The same trend is true for audiences of many symphonies. The New York Times recently said that the age of the average concertgoer at the Metropolitan Opera and New York Philharmonic is 57.

Granek noted that YouTube and livestreaming services offer audiences the option of listening to past and recent records from home without the need for driving downtown to hear live performances. Missing from those listening options are the irreplaceable experiences of hearing concerts in their natural environment and the direct connections to the conductor and musicians that Symphony League volunteers have worked to support for several decades.

The solution for engaging new audience members, Dunleavy said, is a formula that has been playing out since 1957 in Fort Worth. The Symphony League, and similar volunteer groups, need to be more than a fundraising tool.

“When the musicians see us, they know we are the community,” Dunleavy said. “We are not staff. We are not paid. I watch them look up and wave to us. It means a lot to them. They know there are people in the community who appreciate them.”

Courtesy Symphony League

During Harth-Bedoya’s 20-year career as conductor of the FWSO, he saw firsthand how Symphony League volunteers could boost the morale of orchestra members. As they did for Shih, the Symphony League held a baby shower for Harth-Bedoya and his wife before the birth of their oldest daughter, Elena. The maestro said performing arts organizations have a duty to cultivate donors, but they should also find ways to show appreciation for volunteer groups who donate their time.

The Symphony League “should be treasured,” he said. “No money can buy a person who is a passionate advocate for great music.”

Giordano said the Symphony League has long been the bridge between the orchestra musicians and the audience, and it will likely continue to serve that role for the next 65 years and beyond.

“The Symphony League members are working because they love symphonic music and want to keep it alive in this community,” he said. “Without that kind of support, the orchestra wouldn’t exist.”