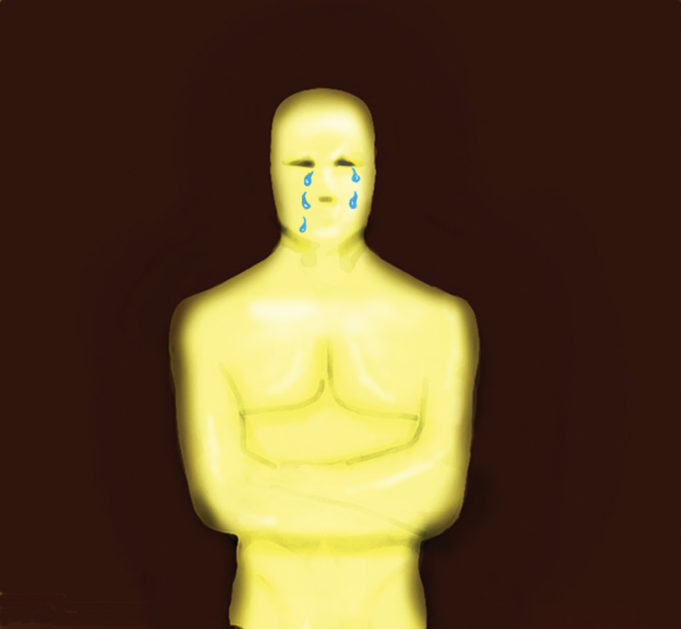

Awards season fills me with dread. It’s not really a “hot take” to point out that watching beautiful people in incredibly expensive clothes hobnob and cheer for their rich and beautiful friends feels alienating, but when you’re a young person who compares herself to others due to low self-esteem, watching the Oscars can leave you feeling pretty empty and unaccomplished.

Yes, I’m aware that sounds melodramatic. “It’s just a party for the rich,” you might say. “Why take it so seriously?”

Remember, feeling bad about yourself isn’t a conscious decision. You don’t wake up one day determined to feel ugly and poor or to question your significance. It’s usually an extension of your mental health. People with chronic anxiety and depression often judge themselves harshly, and usually that coincides with comparing themselves to others, a habit that’s incredibly tough to break.

Cue: the Academy Awards, that magical time of year when we have the privilege of ogling attractive people –– many of whom permeate our popular consciousness during the other 364 days anyway. Actors are granted a level of extreme influence and social capital by nature of their success at entertaining us. They distract us from our everyday lives, and, in exchange, they’re given fame and prestige (along with the harassment, rejection, and criticism that we decide to ignore for a night).

While many people enjoy watching the Oscars for a glimpse into the world of some of the least-relatable people in America, others resent the occasion. Award show viewership has declined in recent years, leading to some attempts from organizers to spice things up, like switching out the traditional red carpet for a Champagne-colored one this year.

I used to enjoy watching the Awards, even looking forward to it every year. It was a fun time to celebrate the films that my friends and I loved seeing in theaters. Perhaps part of my change of perspective came from the pandemic. I can count on four fingers how many times I’ve been in a movie theater in the last year. Since all the films I want to see also premiere on streaming services, my relationship to filmgoing is different. It’s easier to watch movies at home, so the communal experience is gone.

I also think the shift to streaming has changed our relationships to celebrities. Streaming from home makes your connection to the characters (and, by extension, the people behind them) feel more personal. They’re on your turf now. The woman on the massive screen in a theater is a character because we suspended our disbelief the moment we bought our tickets. At home, reality rules, and illusions break more easily — Cate Blanchett or Ana de Armas is now an actor on your TV, just like when we see her on the Oscars and late-night interviews.

Instagram and TikTok have cut our sense of detachment even further. We can click on actors’ Stories and feel as though we’re personally connecting with them when, really, we’re not. We aren’t as free from the influence and curated image of “celebrity” as we were before Instagram and smart TVs, so the self-deprecating can more easily juxtapose our achievements with that standard.

Like many people, I started paying closer attention to my mental health around 2020 and examining my self-talk. I recently noticed certain things make me judge myself particularly harshly. One pain point is dissatisfaction with my achievements. I graduated college with honors, have multiple degrees, and received numerous journalism awards and scholarships, and, at the time, I was proud of every accomplishment. But that was then. What now?

This mindset isn’t unique. Emphasis on accomplishments is a centerpiece of the American ideal. We are supposed to be individualists who make something of ourselves and put productivity and success above pesky luxuries like emotional fulfillment or, you know, sleep and health, but our perception of success is constantly evolving. We meet one challenge and then it loses its value as we establish new standards for ourselves. So, while I have had achievements in life, so what? What have I achieved this year? This month? This week?

Instead of finding awards season inspiring, it reminds me that I don’t have a life plan. I wake up the next day saddened at the thought that I probably won’t ever be able to afford the earrings Jessica Chastain wore Sunday night — that financial security is hard enough to obtain without adding glamor into the equation (no matter how much I’d enjoy that). I watched Michelle Yeoh win her first Academy Award at 60 years old, but then I remembered she’s the exception even in Hollywood. Even the most talented people aren’t always recognized, and many aren’t invited to the Oscars at all.

After watching this year’s ceremony, I understand why I felt relieved when it was canceled in 2020. Because I’ve realized, for people who struggle to feel good about themselves, the subliminal messaging hurts long after the TV is turned off.