Forty years ago, Francis Ford Coppola’s Bratpacker bromide The Outsiders (based on the 1967 S.E. Hinton novel of the same name) made big stars out of Patrick Swayze, Tom Cruise, Matt Dillon, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, Ralph Macchio, and C. Thomas Howell — in reverse order, “Ponyboy” Curtis, Karate Kid, a Breakfast Clubber (and Mighty Duck), the original About Last Nighter, a Drugstore Cowboy, Tom Cruise, and the Dirty Dancing Ghost in Road House. And they capitalized on the opportunity to play underprivileged “greasers” constantly put upon by the well- or better-to-do members of the “Soc” (pronounced so-shis) or high-society set, but at least 100 years before poor white folks in Oklahoma or Italians in New York City were disparaged as “greasers,” the Anglo social set in Texas used the label to dehumanize Mexican and Mexican-American oxcart operators here who worked more cheaply than Caucasian drovers. And the white Texans didn’t settle for just beating up Mexican-American versions of “Ponyboy,” “Dallas,” and “Sodapop” (some of whom had fought for Texas independence). White Texans often murdered them.

On the way back from Corpus Christi in late-July 2018, I drove through Goliad for the first time. Sometimes I take different routes to explore or just loaf a little. I was immediately struck by an incredible tree on the north side of the Goliad County Courthouse, between Commercial and Market streets. I parked, took some pictures, and sat on a bench. I liked the tree. I liked the dramatic appearance of the courthouse through the branches. I spotted a stone-mounted historical marker and examined it. Erected in 1964, the marker for “The Hanging Tree” gave a me a short history lesson.

Site for court sessions at various times from 1846 to 1870. Capital sentences called for by the courts were carried out immediately, by means of a rope and a convenient limb.

Hangings not called for by regular courts occurred here during the 1857 “Cart War” — a series of attacks made by Texas freighters against Mexican drivers along the Indianola-Goliad-San Antonio Road. About 70 men were killed, some of them on this tree, before the war was halted by Texas Rangers.

“Hangings not called for by regular courts.”

Lynchings.

The tree, which I later learned was also referred to as the Cart War Oak, suddenly seemed Lovecraftian.

Here is the first paragraph of the “Cart War” from the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas:

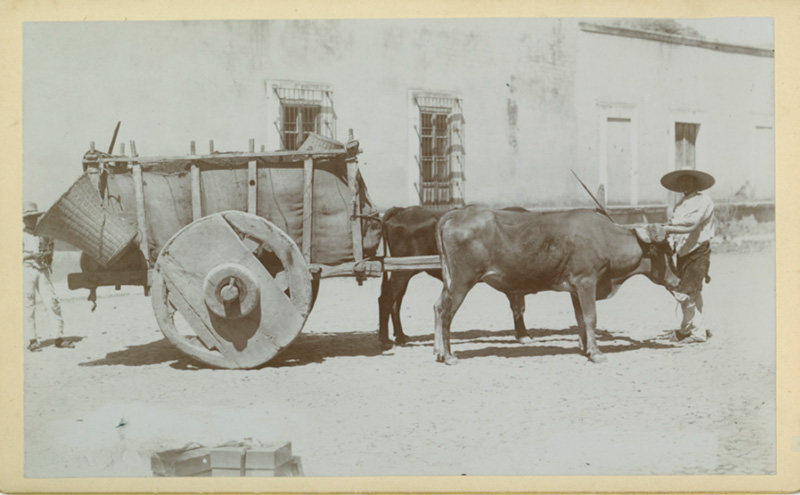

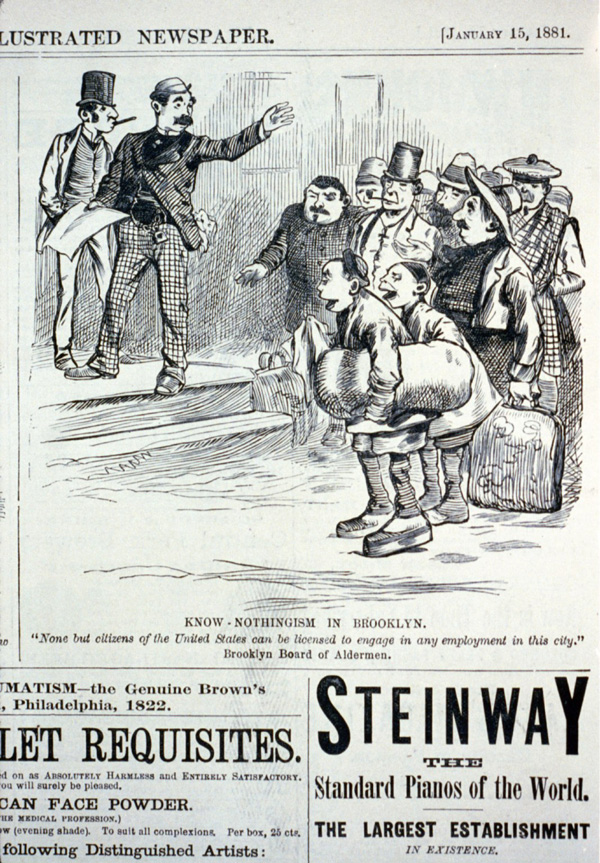

The so-called “Cart War” erupted in 1857 and had national and international repercussions. The underlying causes of the event, historians believe, were ethnic and racial hostilities of Texans toward Mexican Texans, exacerbated by the ethnocentrism of the Know-Nothing party and the White anger over Mexican sympathy with Black slaves. By the mid-1850s, Mexicans and Tejanos had built a successful business of hauling food and merchandise from the port of Indianola to San Antonio and other towns in the interior of Texas. Using oxcarts, Mexicans moved freight more rapidly and cheaply than their Anglo competitors. Some Anglos retaliated by destroying the Mexicans’ oxcarts, stealing their freight, and reportedly killing and wounding a number of Mexican carters.

Courtesy of the Degolyer Library at SMU.

Mexican Americans and Hispanic immigrants taking Anglo Texans’ jobs. Ethnocentrism as in Anglocentrism. And an angry “Know-Nothing” faction in our government that didn’t know much and didn’t care about knowing much.

Sounded familiar.

The local authorities made no serious effort to apprehend the perpetrators of violence against the Mexican-American and Mexican teamsters, much less punish them for their transgressions. And the Sept. 24, 1857 edition of the San Antonio Texan wasn’t having it:

These Mexicans are citizens of Texas, they were born here, and they or their fathers fought against Mexico for that liberty they now enjoy — “liberty,” did we say — rather a poor show for liberty when they are not allowed to pursue their daily labor without being shot down like dogs! And for no other excuse than because they live cheap.

Hardly disproving the Texan’s charge, the Sept. 26, 1857 printing of the Weekly Independent in Belton countered it disapprovingly:

From a gentleman of our acquaintance, who has for something more than a year past been a citizen of San Antonio, we learn that this war has not been waged against Mexican cartmen on account of the difference in the prices they charge for hauling, nor is it believed that other Wagoners are the only ones who attack them, but it is on account of the thieving of those greaser wagoners or cart-men on the road.

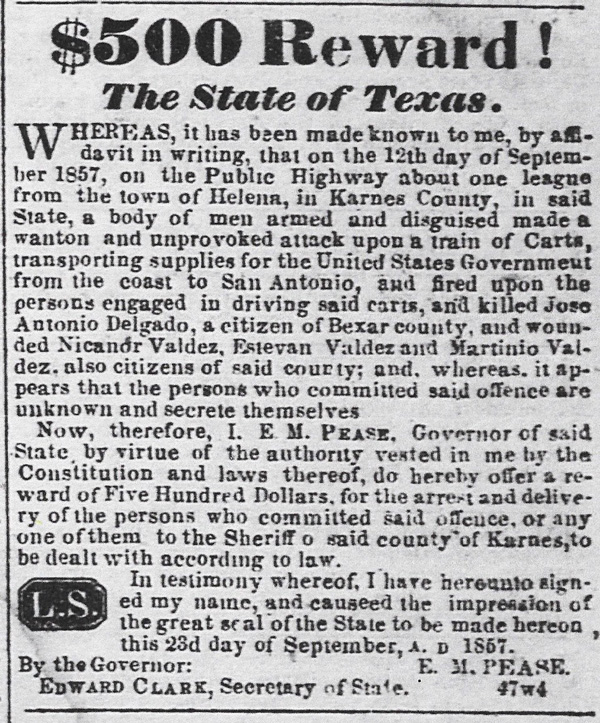

On Sept. 12, 1857, 17 Mexican oxcarts were attacked by 30 to 40 men near Helena in Karnes County. The attackers’ faces were “either masked or blackened,” and they murdered Jose Antonio Delgado, some reports indicating that he had been shot 14 times. Esteban, Martinio, and Nicandr Valdez were also wounded, but Delgado was a prominent San Antonio citizen. He had served under Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812 and was a respected veteran of the Texas Revolution.

Texas Gov. Elisha Marshall Pease subsequently issued a $500 reward for the arrest of any member of the attacking party and urged law enforcement personnel to remain vigilant and enforce the law.

Some accounts suggest that a significant percentage of the trouble occurred around Goliad, and some reports indicate several Mexican-American oxcart drivers were hanged from the namesake Cart War Oak on the courthouse lawn. The irony, of course, is that Texans of Anglo and Mexican descent had gathered in Goliad in 1835 to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence, and only two signatories were native Texians — Jose Francisco Ruiz and Jose Antonio Navarro. All the rest were immigrants from somewhere else — white Anglo immigrants.

As the violence continued to escalate, Mexican minister Manuel Robles y Pezuela protested the bloodshed to U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass, who, in turn, urged Pease to take action. On Nov. 30, 1857, the governor addressed the Texas Legislature and requested a special appropriation:

Information has been received at this office, that a train of carts, from San Antonio to the Coast, driven by Mexicans, and under the charge of Mr. Wm. Pyron, an American, encamped on the night of the 20th on Yates Creek, the next morning while the Mexicans were getting up their oxen. They were assaulted and fired upon by a party of armed men, and two of them were killed.

No blame whatever attaches to Capt. Nelson or the company under his command, as Mr. Pyron did not apply to them for an escort. It is understood that he preferred to go without an escort, in consequence of assurances of safety that had been given him by parties in Karnes and Goliad Counties, he having previously made a trip without molestation.

After this misfortune Mr. Pyron returned to the Cibolo, where Capt. Nelson’s Company were encamped, and applied for and received an escort for his train.

It is painful to have to record such acts of violence, and a subject of deep mortification that the law places no means in my power to prevent them. Such outrages cannot occur and pass unpunished in a country where the Officers and the mass of the people entertain a proper respect for the laws. And it becomes a matter for your consideration, whether the citizens of a country that permits such acts to be done with impunity, should not be compelled to pay a heavy pecuniary penalty. This would, without doubt arouse them to the necessity of preserving the public peace.

It is now very evident that there is no security for the lives of citizens of Mexican origin engaged in the business of transportation along the road from San Antonio to the Gulf, unless they are escorted by a military force. The term of service of the Militia now employed will expire on the 8th day of December, and unless some direction is received from the Legislature to continue their services, I shall feel it my duty to discharge them on that day.

It will require an appropriation of about fourteen thousand and five hundred dollars to pay the services of the Company, and for their subsistence and forage.

Courtesy Wikimedia

Upon the approval of the appropriation and the deployment of armed escorts, the Cart War reportedly ended in December 1857, but there were Anglo grumblings all the way. A commentary in the Dec. 5, 1857 edition of the Belton Weekly Independent was chilling and remorseless: “That there were some Mexicans killed no one denies, but that as many were killed as ought to be, we believe no one will admit.”

On Saturday, Jan. 23, 1858, the Colorado Citizen (of Columbus, Texas) “remonstrated against” Pease’s action and held forth in a classless (or class-minded), racist manner:

That the citizens of Goliad and Karnes have been harassed to death by contemptible Mexican greasers or peons, we have not a doubt. We respect a decent Mexican citizen, but for these low, thieving Mexican peons, we have no sympathy — they are not deserving of it. We remember that about two years ago some of them were driven out of Caldwell County by citizens for tampering with slaves, and inducing them to run off to Mexico; and in the summer of ’56, during the inchoated negro insurrection in this county, some five or six Mexicans were implicated in the insurrection and banished by our citizens. Some of these Mexicans had negro wives and placed themselves on an equality with the negroes.

The truth is this class of Mexicans are no better than negroes and we had as soon go to the polls and vote with a free negro. We do not say this in disparagement of the more respectable class of Mexican citizens; for we are aware that there are such, and as such they are entitled to the same respect and privileges that American citizens are. We do not know, but it seems to us it would have been more proper and wise in the Governor to have let alone the matter and left the citizens of Goliad and Karnes to settle the difficulty themselves. We doubt not there are enough good, law-abiding citizens in these counties to insure [sic] justice to all parties, and to deal with the Mexican greasers or peons — who, it appears, from the testimony of our correspondent, are connected with abolitionist associations, and are running off slaves into Mexico — in accordance with true patriotism and the spirit of our institutions.

This opinion was not isolated.

The majority of white Texans of the period had come to consider their Mexican and Mexican-American neighbors “as racially inferior, culturally defective, and morally corrupt,” and, actually, two years before the Cart War officially commenced, the Austin-based Texas Gazette printed a prescient story titled “Worthy of Notice”:

A Writer in the San Antonio Ledger suggests that every Peon Mexican coming to San Antonio be compelled to register his name at the Mayor’s office, and give an account of himself and his business; that, also, if he is unknown to any respectable resident of San Antonio, and unable to give a satisfactory certificate, that he be required under penalty of law to leave the city forthwith. It is a most troublesome class in the community — one far more mischievous than free negroes, and they are doubtless all of them fugitives from service and labor in Mexico. Something of a stringent nature ought to be put in force against them. We may suffer the peon to stay among us who labors and shows himself to be honest and industrious, but we cannot permit the peons to increase in our community unrestrainedly without serious loss to citizens. It is a bad element of society, and sooner or later will be entirely extinguished.

Wikimedia

In 2018, Utah State University Professor Maria Diaz placed the entire situation in context: “The Cart War in Texas encapsulated a period in which the place of Mexican laborers — and, indeed, the Mexican people writ large — was defined by the limits of a white/Black binary. In the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War, more Southerners migrated to Texas, slavery continued to take root, and Mexican Texans became entangled in a world not of their own making — one in which they were caught in between social classes and racial castes.”

As Texans have embraced selective amnesia as government policy of late, the Cart War is almost entirely ignored, but such was not always the case.

In a Texas Siftings piece reprinted in the July 18, 1885 edition of the Palo Pinto Star, the affair was far from forgotten and the story even discussed a fascinating warning “sign” that remained for years after the bloodshed:

One of those old-fashioned wooden wheels would be a curiosity nowadays in San Antonio. There is only one in the country, and it is up in a mesquite tree in Atascosa County. It got there in a very singular way.

About 1856 the American teamsters, who competed with the Mexicans in transporting freight to San Antonio, discovered that they were being ruined by cheap Mexican labor. The San Antonio merchants preferred to have their goods brought from the coast by Mexican carelas, for the reason that the Mexicans were more reliable. They did not extract whisky from the barrels and fill them up with water, and help themselves generally to the goods entrusted to them, as did the Anglo-Saxon teamsters, whose go-ahead-ativeness could not be repressed.

The result was “the Cart War,” in which many Mexicans were killed, and their carelas burned. The old-fashioned wooden wheel, away up in a mesquite tree, marks the site of one of these fights. For some reason or another, the American teamsters stuck the wheel up in a tree, possibly as a warning to other Mexicans. A limb of the tree grew through the hole in the wheel, and today it looks very peculiar up on the tree to a stranger, who imagines that the tree grew up suddenly under the wagon, while it was passing, and tore a wheel off.

In A New History of Texas for Schools by Anna J. Hardwicke Pennybacker of Palestine, Texas, the citation for the “Cart War” appears as follows:

At this time Mexican teamsters were doing most of the hauling from the seaports to San Antonio, for they worked more cheaply than Texas wagoners, and were quite as reliable. In spite of public warnings, farmers and merchants continued to employ the labor they could get for the least money. The Texas workmen then attacked the teams of Mexicans, stole their goods, killed their animals, destroyed their wagons, and, in some cases, murdered the drivers. Indignant at the cruel treatment inflicted upon his countrymen, the Mexican Minister (October, 1857) complained to the United States authorities. In November, Governor Pease sent two special messages bearing on this subject, to the Legislature, and finally, to protect the Mexicans, ordered out seventy-five militiamen, who, with the assistance of law-abiding citizens, restored order.

The mention could be construed as progress, except that Pennybacker’s textbook was published in 1895 and hardly anyone has heard of the Cart War today. That or the conflict never really ended (and no one wants to talk about it).

The 110th anniversary of the Karnes County bloodshed that killed a Republic of Texas patriot was a few weeks back, but the Texas lege has crippled our state education systems, and though some concerns have been expressed about how the increasing number of God, guns, and white privilege advocates fleeing to Texas are sapping our dwindling water supply, even clouds of dust have a silver lining.

There’s more and more sand for us to bury our heads in.

E.R. Bills is the author of Tell-Tale Texas: Investigations into Infamous History.