Feeling Color: Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling celebrates the work of British-Caribbean artists Aubrey Williams (1926-1990) and Frank Bowling (b. 1934). The artists’ contributions to the story of abstract painting in the late 20th century were significantly influenced by their migration from British Guiana (now Guyana) in South America to Britain and beyond in the 1950s. The artists left social upheaval in their native country, both landing (ironically) in the nation that colonized their homeland.

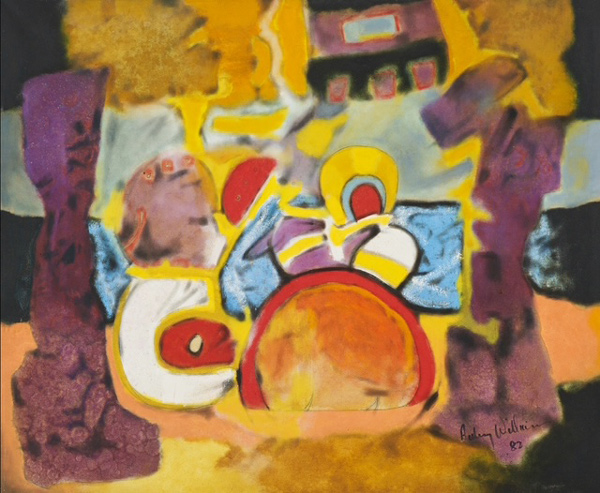

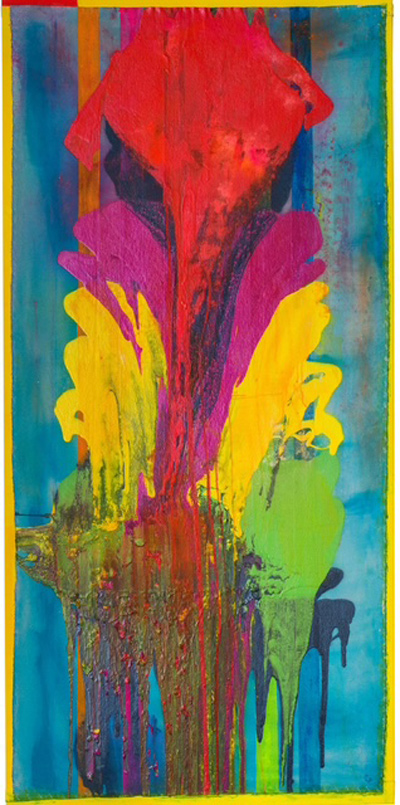

Up now through July 27 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, the show was organized by Curator María Elena Ortiz, who joined the Modern as curator in 2022. She comes to Fort Worth from the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), where she was also curator. Ortiz founded and spearheaded PAAM’s Caribbean Cultural Institute, a curatorial platform dedicated to Caribbean art. Ortiz has a history of diversifying museum collections, and she’s well-placed at the Modern. Feeling Color presents works from Williams’ series Shostakovich (1980-81) and The Olmec Maya and Now (1982-88), while Bowling’s works include his Map series (1967-71) and his later poured paintings, which push the limits of abstract art.

Many of us equate abstract art with Picasso or perhaps the rampant paint splatters of Jackson Pollack. Mark Rothko’s vibrantly colored rectangles and the street art of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat may also ring a bell. With Feeling Color, Ortiz turns the focus on two Afro-Caribbean painters of the ’60s who were part of a larger migrant movement as the British Empire’s former colonies shrugged off their colonizers. While both Williams and Bowling hail from the former British Guiana, their styles and life experiences are markedly different.

The late Aubrey Williams was the son of a civil servant in British Guiana. Although he was a talented artist as a young man, he became a field officer in the nation’s agriculture department in the late 1940s. A stint on the sugar plantations on the nation’s eastern coast radicalized him, because he saw how hard the subsistence farmers worked and how little they took home. Williams helped the farmers organize to demand fair trade from the Britons. His “reward” was banishment to a tiny ag station in the northern rainforest, where he worked with the Warru tribe. Immersion in the Amerindian culture profoundly influenced his future work. Two years later, he returned to Georgetown, where his revolutionary advocacy to shake British rule from Guiana caused the Guianese authorities to make life uncomfortable. Williams migrated to Britain in 1952, ostensibly to continue agriculture studies at Leicester University. He gave up the student role for one of travel and immersed himself in the post-war art scene in Europe. He enrolled in London’s St. Martin’s School of Art, exhibiting in several galleries. Williams was influenced by abstract-expressionists like Pollack and Rothko, along with Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose symphonies and quartets formed an auditory backdrop in the artist’s formative years as he painted in his London studio.

Courtesy the Modern Museum of Fort Worth

The title of the exhibit comes from an interview with Williams, who said that when heard Shostakovich’s work, he could “feel color.” Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Williams worked and exhibited internationally in Jamaica, Guyana, and Florida. He died of cancer in 1990.

Richard Sheridan Franklin Bowling, OBE, is Williams’ contemporary with a similar migration story. Sir Frank (the artist was knighted in 2020) has been called one of Britain’s greatest living abstract painters, and he was the first Black artist elected to Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts. Bowling migrated to London just after Williams, but his trajectory was a little different. Bowling moved to live with family in London with the stated objective of studying English with an eye toward becoming a writer and poet. He did a stint in the Royal Air Force and afterward became an art student. He ultimately won a scholarship to London’s Royal College of Art around the same time as David Hockney, one of the pioneers of British pop art. By the mid-1960s, Bowling had studios in London and New York City and was leading a jet-set life. Through his work and writings, he continuously promoted the idea that Afro-Caribbean people do not fit neatly into a checkbox marked “Black.” As of this writing, he continues to work daily in his art studio.

It’s interesting to compare the two artists Ortiz has pulled together, especially considering they worked in parallel. Their similar backgrounds belie the divergence of their work. The Modern says, “These works reflect the artists’ histories by combining modernist abstraction with, in Bowling’s case, imagery derived from African diasporic dwellings and, in Williams’ case, the Indigenous cultures of South America, each pointing to the complexity of their postcolonial heritage. These are works that embrace color, movement, experimentation, and abstraction to convey human emotion.”

Williams’ premature death came at a time when people were rediscovering him as an artist of significance. Ultimately, both artists were recognized as pioneers of the late-’60s Caribbean Arts Movement, a short five-year post-war heyday of Afro-Caribbean joy featuring art from diaspora painters from British colonies and former colonies. The loose collective of artists, poets, filmmakers, and others was a hive of creativity for West Indian migrants, folks running from corrupt governments like Williams, and Black Britons.

Curator Ortiz has compiled a wildly colorful set of both artists’ work, expanding the artists’ stories for those who are learning about the works for the first time. Some of the art feels familiar, but much of it looks novel if you’re only now learning how multidimensional abstract art is. Feeling Color is the inaugural presentation of the Modern’s program Platform, which “seeks to link a variety of contemporary artists and art histories from across the globe.” Well done.

Feeling Color: Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling

Thru July 27 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell St, Fort Worth. Free-$16. 817-738-9215.

Courtesy the Modern Museum of Fort Worth

Courtesy the Modern Museum of Fort Worth