It’s hard to keep a tally of how many basic artistic constructs and motifs are tweaked or altogether upended in Disappearing –– California c. 1970.

Hanging now through August 11 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, this show all but redefines “performance” art as a special hybrid of self-expression.

Most crucially, the exhibition presents in a bracing new light the spiritual and corporeal notion of “disappearing” through the stunningly protean output and media of the show’s three principal artists. Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, and Jack Goldstein barnacle onto the act of physical disappearance as part of their individual art. Furthermore, each of the California-based artists decided to erase themselves from their daily routines (temporarily, of course) while artistically charting what that “invisibility” looked and felt like.

It is essential to understand that the exhibition’s three artists migrated to California – Ader from Holland, Burden from Massachusetts, and Goldstein from Canada –– and would soak up, if not reflect, the heady ferment of the ’60s- and ’70s-era California art scene.

Disappearing –– California c. 1970 is a multimedia extravaganza with a patron absorbing everything from found objects, acrylic on canvas, wire, light bulbs, hulking sailboards, and thousands of nickels, to nostalgically flickering 16-millimeter films using vintage Bell and Howell projectors.

From the show’s first work, Bas Jan Ader’s “Please don’t leave me” (1969), written in an imposing font on the wall, the darkly romantic tone of the exhibition is established, in which “leave” augurs the twin themes of abandonment or disappearing that resonate throughout the subsequent galleries.

Found objects form the core of Burden’s “Survival Kit” (1979). Such banalities as a toothbrush, a cluster of matches, and a stubby candle reflect Burden’s concept of what will be absolutely essential for survival alone in a possibly dystopian world. And then in the purest sign of Burden’s fascination with self-erasure, “Disappearing” (1971) shows an empty box –– a literal void –– which is all that Burden provides as evidence of his theatrically illusory “disappearance.” As he is quoted in the catalogue, “I disappeared for three days without prior notice to anyone.”

The first of the show’s 16-millimeter filmed “performance” pieces is “Fall 1, Los Angeles” (1970) and features Ader in a sequence of Buster Keaton-worthy slapstick as he tumbles off the shingled roof of his low-slung California home. It was purposely shot in one take and captures a grainy documentary truthfulness. In “Fall 2, Amsterdam” (1970), the artist expertly steers his bicycle off an Amsterdam sidewalk into a bordering canal. With a splash, Ader disappears in this quintessential example of dark-humored performance art.

The first of Goldstein’s several works, “Jack” (1973), is also a 16-millimeter film of the artist at first captured in close-up. Then he starts to recede into a moonscape-desert background, all the while uttering his name, “Jack,” in a voice growing fainter as he “disappears” into the desolate landscape.

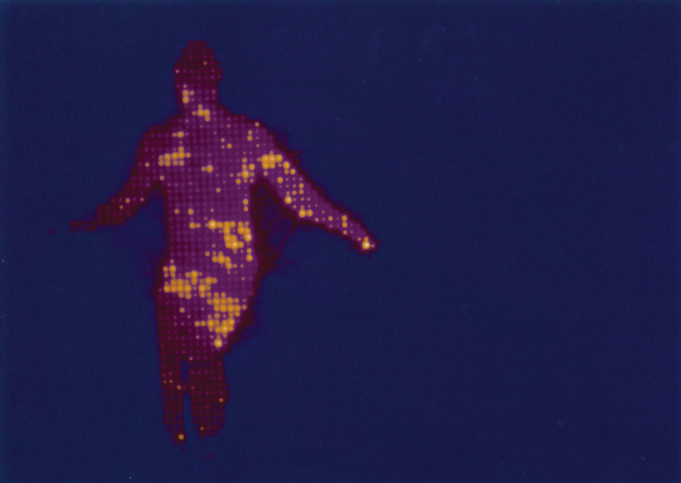

Meanwhile, Goldstein’s “The Jump” (1978) has redefined man into a pixilated, black-lit, 16-millimeter-shot animation doing acrobatics. In essence, Goldstein has disappeared his subject, converting the human form to a 26-second kinetic force field with no discernible human features left.

Burden is very much central to his personal act of exile as he bicycles across Death Valley, all captured in “Death Valley Run” (1976). Composed of seven pictures, several of the white T-shirt-clad Burden are central to documenting this private, brazen act of removing himself from civilization –– at the potential cost of his life.

Also on display in jaw-dropping scale is Burden’s “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb” (1979), which required the installation of 50,000 nickels, each one holding a jagged-edged match stick, all as metaphor for the 50,000 Soviet tanks in the enemy’s menacing arsenal enforcing its then-occupation of Eastern Europe.

Though not the final piece in the show, Ader’s three-part “In search of the miraculous” (1975) ensured that he was the only one of the three artists who pursued his art of disappearance to tragic ends. After still shots of a local student choir crooning old time sea shanties, a patron then watches home movie-quality footage of Ader’s launch party for his one-man, merely 12-foot-long sailboat (christened the “Ocean Wave”) for his ultimate disappearing act: crossing the Atlantic solo.

But Ader never survived the voyage. His battered boat eventually drifted ashore but without his body.

While Burden eventually succumbed to cancer and Goldstein committed suicide, it was the 33-year-old Ader who created the ultimate expression of disappearance by literally dying for his art –– thousands of miles away from the California studio that launched an abbreviated lifetime’s worth of rich self-expression.

Disappearing — California c. 1970: Bas Jan Ader, Chris Burden, Jack Goldstein

Thru Aug 11 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell St, FW. $10-16. 817-738-9215.