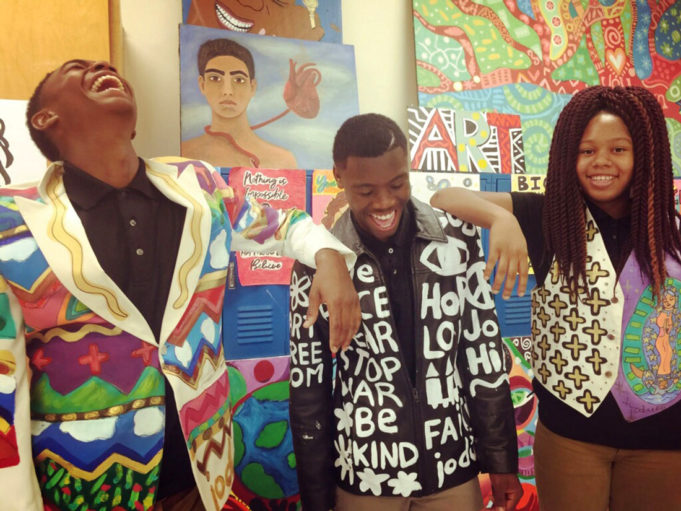

When Jo Dufo retired from teaching art at Metro Opportunity High School last December, she assumed the programs would continue serving the at-risk students who rotate through the alternative high school every two to three months. Dufo personally oversaw the training of her replacement before moving to Chicago to be with her terminally ill daughter.

Last week, word began to spread that the art class was going to be replaced by an online course. Local artist and community organizer Arnoldo Hurtado posted about the decision in his Northside Community Facebook group. The post, which featured a link to my cover story about the program (“Staying Positive,” Sept. 2017), had nearly 60 shares.

“If this trend of cutting access to the arts in education continues, our students, family members, and kids will be cut off from more and more forms of expression,” Hurtado said. “Internalizing troubles, feelings, thoughts, and traumas that led students to be sent to Metro in the first place will only lead to more frustrations and issues.”

The post caught my attention, partly because I had the opportunity to sit in and watch Dufo use art to spur discussions on values, goals, and life with teenagers who came from broken homes and have difficulties that few could ever imagine facing, let alone at such a young age. One boy I interviewed was struggling to understand why his father was incarcerated. The kids were incredibly open to Dufo, and she treated each of them in turn with kindness and compassion.

“Never see yourself through the eyes of the world,” she told her class in 2017. “You may crawl, walk, or run. If you slip, be kind to yourself. Be kind. Always encourage yourself to become better. And you will be amazed at how far you will come.”

When I reached out to Dufo, she was still grieving over the death of her daughter. Sierra Dufault, Dufo told me, had become a successful artist in Chicago before a tragic illness took her life. Had I known that Dufo had recently lost a child, I would not have imposed on her with a phone interview. Dufo was adamant about helping the Metro Opportunity High School art program in any way she could, so we talked.

“It’s sad,” she said. “Sometimes, the people who need something the most are the people who are denied it. The kids there benefited from being outside of overcrowded classrooms and in an area where they could have a personal connection with the teachers. The art room has been the soul of the school.”

To outsiders and school administrators, an art class that serves only a handful of students at a time may seem like an expendable luxury, but for the children who entered Dufo’s class, the experience was often remembered as life-changing.

“Mad love for this woman,” a former student recently posted on Instagram. “She cared for me like a son and helped me realize that I don’t have to be a young, black stereotype. She slowed me down and opened my eyes.”

When the Weekly cover story ran two years ago, the fact that many public schools, especially in poorer urban areas, act as a school-to-jail pipeline was not lost on us. The story noted that around 80 percent of adults in Texas prisons are high school dropouts, according to research by Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit public-interest law center. Dufo and her colleagues were very much in the front lines of preventing young minds from becoming old prison inmates. Rather than treat the alternative school like a prison and enforcing punitive measures, the staff at Metro Opportunity High School used their time with the teenagers to uplift them through group meetings, supportive language, and “real talk,” which allowed students to discuss what was happening in their personal lives without fear of being judged.

“We realized that these kids are facing incredible challenges,” Dufo said. “If someone doesn’t show them some love and kindness, these kids are going to continue down that path of being angry. They need people to care and to show them that they are worth something.”

Art classes, unlike online courses, are uniquely suited to engage students while allowing them to relax and to open up about how they feel.

“When you have your hands moving and you’re creating, it distracts you from being so guarded,” Dufo said. “You’re open to express your feelings in those situations.”

Fort Worth school district spokesperson Clint Bond said in an email that the district has a “mandate to use [public funds] we have as efficiently as we can. Sometimes that means we have to make hard decisions about changing certain aspects of the programs we offer based on student interest and enrollment, for example. It is important to understand that [the students] have the opportunity to return to their home campus, upon completion of their assignment to Metro, where art classes are offered in a hands-on environment.”

Dufo said she would teach the class again if offered the opportunity. The fact that school officials would cut a program that serves the most vulnerable and at-risk students in Fort Worth is upsetting to her.

“What message are they sending,” she said. “It’s easy to turn your back on low-income people and to focus on people who are perceived as higher achieving.”

Jo Dufo is a remarkable woman who I know only through facebook. I am a former teacher and have a particular place in my heart for at-risk kids. (My pipeline was literature.) How tragic that this program is being cut back or eliminated.