The teacher was stunned at what she saw at this year’s Arlington Heights High School graduation — and not in a good way. “I saw at least 22 kids get their diplomas who I knew had missed so many days that there was no way they could have made up the credits they needed in time to graduate,” said the teacher. “I asked myself, ‘How did that happen?’ ”

It happened with help from the school principal and three members of her administration, six staff members say. According to the staffers and to documents obtained by Fort Worth Weekly, the top school officials cleared hundreds of unexcused absences from attendance records this year, as part of a campaign to lower Arlington Heights’ dropout statistics and keep the school from again being declared “unacceptable” in the state’s critical academic ranking.

For some students, making up lost credits was as easy as picking up a dust cloth. Others were allowed to wipe out failure by spending a few hours in front of a computer screen. But many other absences, the staffers said, were made to disappear by administrators who simply altered the records.

For some students, making up lost credits was as easy as picking up a dust cloth. Others were allowed to wipe out failure by spending a few hours in front of a computer screen. But many other absences, the staffers said, were made to disappear by administrators who simply altered the records.

If the accusations of attendance fraud are proved correct, the repercussions could be profound: The district could be forced to pay back tens of thousands of dollars in per-capita funding to the state, educators involved could lose their certification and perhaps their jobs, and almost two dozen kids who graduated in June could find their diplomas in jeopardy.

“In January … I personally wit-nessed Principal Neta Alexander altering a student’s attendance. … As we approached graduation, the manipulation of attendance was completely out of control,” an assistant principal wrote in a complaint filed with the school district in June against Alexander and two assistant superintendents. He has asked that his name not be used until his case has gone through the district’s administrative process.

However, attendance fraud is only one of the charges now being investigated by the Fort Worth school district’s Office of Professional Standards. The allegations were detailed in dozens of supporting documents filed with the complaint. Those and other documents received by the Weekly, as well as interviews with Arlington Heights employees, paint a picture of a school that at times over the past three school years has verged on anarchy — while Alexander and her allies reportedly did everything they could to keep the school’s problems from coming to the attention of the school board, the parents, or the general public.

The staffers describe racial tensions that led to numerous fights — including some that resulted in serious injuries to students — physical fights between faculty members, a death threat made by a parent against an administrator, guns brought to the campus at least twice, and several incidents in which out-of-control students physically threatened teachers and had to be wrestled to the ground by other staffers.

One of the more terrifying events happened two years ago and could have led to multiple deaths and injuries, according to a faculty member who witnessed it: A student brought a potentially lethal bomb to campus, placed it on a math teacher’s desk, and left the building. The only reason it didn’t explode, the teacher said, was that the student, who was found with a remote detonating device in his pocket, had improperly installed the detonator.

Bomb threats were not uncommon, another staffer said. One student called in two bomb threats last year and received only a three-day suspension, he said.

That’s not all. Several teachers said that academically low-performing students were allegedly suspended days before the state accountability tests so that they could miss the tests for an acceptable reason. The complaint documents charge that tens of thousands of dollars in electronic equipment went missing from a female coach’s house and is still unaccounted for. This same coach, the documents state, was known for cursing at students, frequently describing her sexual exploits in obscene language to teachers and students, and conducting an affair with an administrator who used students to pass love notes to her. Teachers said that the coach and the administrator were also involved in the attendance fraud, along with another assistant principal.

![feature_1 Sutherland: “I am dismayed that we were asked to approve proposed [personnel] ... changes ... without being informed of the scope of this investigation.” Photo by Jeff Prince newbettypic](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/images/stories/images/8-11-2010/newbettypic.jpg) Arlington Heights school board representative Judy Needham told the Weekly that the internal investigation was opened in May, shortly after she was given copies of the allegations and passed them along to Fort Worth schools Superintendent Melody Johnson. However, faculty members said the allegations were brought to the administration’s attention much earlier.

Arlington Heights school board representative Judy Needham told the Weekly that the internal investigation was opened in May, shortly after she was given copies of the allegations and passed them along to Fort Worth schools Superintendent Melody Johnson. However, faculty members said the allegations were brought to the administration’s attention much earlier.

“The investigation is open and ongoing, and we intend to give our employees due process and the right to a thorough investigation,” district spokeswoman Barbara Griffith said. “Until that process is completed, we will not comment further or take a position.”

Since June, as details of the charges began to leak to a few board members and the press, two staffers named in the allegations (including the foul-mouthed coach) have resigned and three have been moved to other schools. Among the three were the assistant principal and main whistleblower, who was moved to an assignment that he considered a major demotion. (Another assistant principal, who was not involved in the alleged fraud, has been transferred at his own request.)

Alexander has also been transferred — but to a plum assignment at one of the district’s academically strongest high schools. She declined to be interviewed for this story because of the ongoing investigation.

Now, however, both of those reassignments are under scrutiny.

The full school board was not briefed by Johnson until this week, a delay that has angered some trustees, since they were asked two months ago to approve personnel changes involving faculty members named in the investigation. Nor were they told at that time that one of the reassignments was that of the key whistleblower, nor that he had strenuously objected to the transfer.

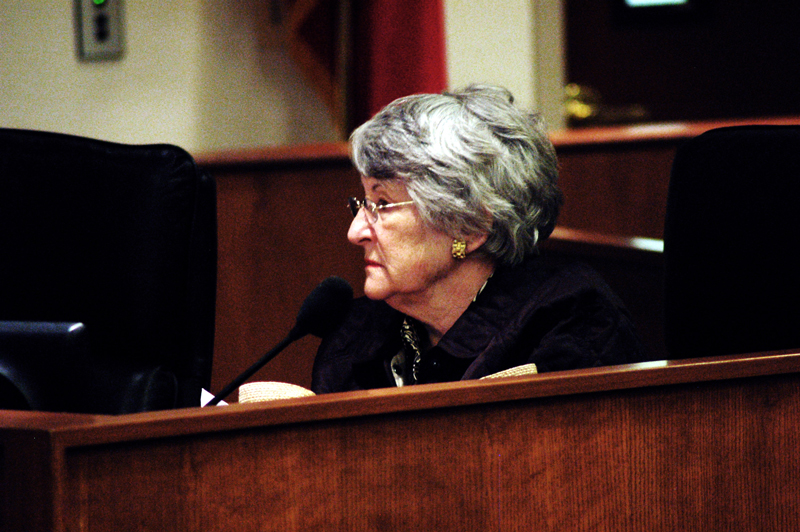

“I am dismayed that we were asked to approve proposed [personnel] changes in a situation of this apparent magnitude without being informed of the scope of this investigation,” board member Ann Sutherland said.

The whistleblower refused his new assignment, filed a complaint of retaliation, and is considering suing the district. He is represented by Linda LaBeau, a professional mediator, and Larry Shaw, head of the United Educators Association, the district’s largest teacher union. Both say the assistant principal believes he was demoted in retaliation for reporting the allegations to top district officials, even though that was his job as the school’s diversity coordinator.

School district administrators insist the transfer was the result of a poor evaluation from Alexander. Shaw rejected that: “This is a classic tale of killing the messenger.”

In the last few days, as news of the fiasco at Arlington Heights began to spread, district administrators abruptly withdrew the transfer order for the assistant principal and sent him to yet another school — where his new boss didn’t even know he was coming.

“I don’t know what is worse, the acts themselves or the people trying to cover everything up and retaliate against us,” one Arlington Heights staffer wrote in an e-mail to LaBeau.

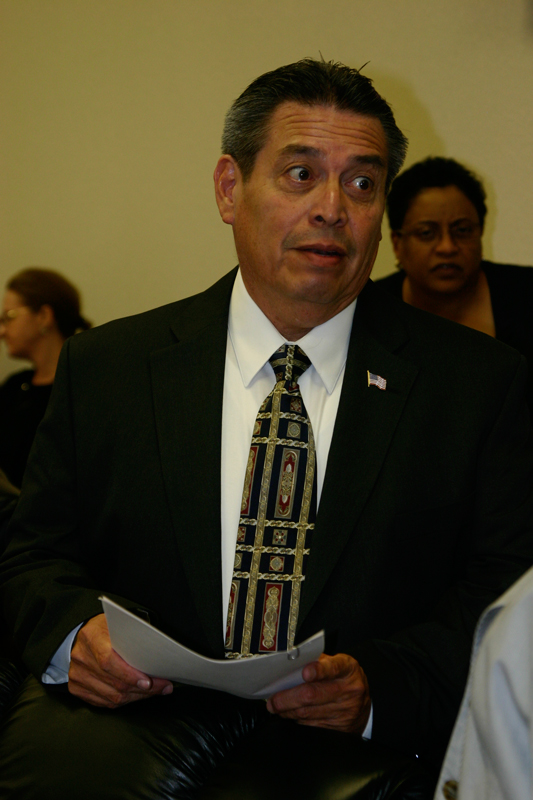

Trustee Juan Rangel, who represents the high school where Alexander has been reassigned, was blunt: “This calls for an outside, fully independent investigation. The district cannot investigate itself on this one.”

That just might happen. On Monday the assistant principal took his case to higher authorities, LaBeau said: He reported the alleged wrongdoings to the Texas Education Agency and the state attorney general and requested that both agencies investigate.

The half-dozen Arlington Heights teachers and others who spoke with the Weekly said that Alexander — who is popular among students and parents — has long been determined to avoid negative publicity about her school.

This past year was even worse, they said, because the principal was obsessed with lifting the taint of the “academically unacceptable” rating the school received in 2009. And that obsession, they believe, led to her decision to allow a couple of her closest administrators to manipulate attendance records.

Even when a high school meets the requirements under the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills tests, as Arlington Heights did last year, if its completion rate (i.e., percentage of students who graduate on time) drops below a certain point, it will be stamped “academically unacceptable.” This year the school raised its completion rates enough to receive an “academically acceptable” rating. Some teachers say that was only because the attendance records were altered.

The most damaging evidence of fraud may lie in the assistant principal’s complaint, which says that he has given district investigators “dozens of documents illegally changing attendance” signed by two assistant principals and Izzy Perry, who was the head girls’ volleyball coach. The documents he turned over to the Office of Professional Standards, he wrote, “had been provided by teachers, clerks, and staff.”

If the district’s internal investigation finds the charges of attendance-record tampering to be accurate, the Texas Education Agency could get involved, agency spokeswoman DeEtta Culbertson said. She confirmed that if the records are inaccurate, the district could have to pay back substantial amounts of state funding. Culbertson also said TEA could get involved, regardless of the outcome of the district investigation, if it received a complaint directly from an individual.

According to the TEA, state funding for public schools is allocated on an annual per-student basis, figured on each school’s average daily attendance. Districts got $4,765 per student from the state for 2010, an amount that covered more than half of the Fort Worth district’s cost to educate its students. At the end of the school year, schools must document what percentage of their students actually showed up for class. If attendance falls below a certain percentage, that school’s funds for the following year are reduced accordingly.

Under the Texas Administrative Code, educators are not allowed to “falsify records, or direct or coerce others to do so.” The TEA is empowered to investigate allegations of ethical wrongdoing in such cases and can pull the certification of any teachers found to have been involved.

According to teachers’ statements that were filed with the whistleblower complaint, as well as documents provided to the Weekly by others, a dozen members of the school’s faculty and staff at one time or another witnessed the altering of attendance records.

One staffer said that when students go to truancy court and then return to class, the teacher must sign a book each day testifying that the students indeed were there. When students didn’t show up and the teachers refused to sign the book, the staffer said, he saw Alexander signing the books stating that the students were in class. According to Bertha Whatley, head of the district’s legal department, 146 referrals of Arlington Heights High School students were made to the truancy court last year.

The potty-mouthed female coach and two assistant principals, one of whom was her boyfriend, were given authority by Alexander to “correct” the absentee rolls, several teachers said.

A high level of absenteeism also threatens the school’s overall rating, because it affects whether truant students are given a chance to do remedial work to get credit for courses they need to graduate.

If students show up less than 75 percent of the time, they are not allowed to make up those classes, and they receive no credit for the course.

Fort Worth schools keep separate attendance records for students who are absent six times or more in any class in a given semester. This year, according to teachers who have seen the original attendance records as well as the corrected ones or who had chronically truant seniors in their classes, at least 20 seniors had attendance rates in some classes that were far below the minimum required level. Some were absent from 44 to 66 times out of 108 school class days in the spring semester.

One document, provided to the Weekly by a teacher and dated June 4, two days before graduation, lists 73 seniors with some names underlined, some highlighted, and some circled. An unsigned handwritten note on the document states, “highlighted students still in danger (23) — circled students need absence correction … to fix on computer — crossed out names are already good!”

One document, provided to the Weekly by a teacher and dated June 4, two days before graduation, lists 73 seniors with some names underlined, some highlighted, and some circled. An unsigned handwritten note on the document states, “highlighted students still in danger (23) — circled students need absence correction … to fix on computer — crossed out names are already good!”

In all, 12 names were crossed out. By graduation, 11 more were cleared of attendance problems.

In fact, high truancy rates were a problem in all grades at Arlington Heights. In a school with an enrollment of 1,755, “about 800 unexcused absences were made to disappear,” one teacher said.

Other students with high absentee records or who had failed a course were given another option to get credits they needed for graduation. One teacher reported that for at least three years there has been one Saturday set aside as “senior amnesty day,” as the teachers call it.

The administration would “pick the kids with the most absences” who would not otherwise graduate and allow them to come in for two or three hours on “Senior Saturday” and make up those unexcused absences and credits. All they had to do, the teacher said, was sit in front of a computer program called Plato, read some text, answer a series of questions, and — voila! — the credit was earned. The school has been using Plato for three years.

Seniors could make up all of their missed credits in a couple of hours, she said, even though “technically in a four-hour period you are only allowed to work off four [days’ worth of] absences.”

One student who used the program described it as “more than easy.” After a few practice sessions, in which they are directed to the right answers, students can pass the test easily, he said.

One student who used the program described it as “more than easy.” After a few practice sessions, in which they are directed to the right answers, students can pass the test easily, he said.

The program has drawn controversy around the country. Still, the teachers interviewed said that Plato is probably more legitimate than the practice they call “cleaning for credit.”

“The problem at Heights,” one faculty member wrote in an e-mail, “is that there were numerous students absent in excess of 75 percent [of the time] who knew they could simply ‘skate’ by an ‘approved lesson plan’ consisting of concession stand work, dusting, moving furniture, or going to Starbucks [on behalf of] a coach. Those students were in addition to the ones who wiped out their sins with a Plato session, he said.

The reason for allowing such substitutes for actual learning, several teachers suggested, was Alexander’s determination to keep up graduation rates — and also her emphasis on pleasing her students’ parents.

“Don’t make the parents unhappy,” was her mantra, another teacher said.

There are legitimate ways for students to make up unexcused absences under the state’s attendance laws, but they don’t include sweeping and dusting. Yet dozens of kids were witnessed doing just that in the last weeks of school this year and even after summer school opened.

When a group of students with cleaning supplies were being disruptive in the halls during a Saturday session at the school, teachers asked them to leave. The students responded that they couldn’t leave because they were “dusting for credit,” one teacher said.

Another staffer wrote, in an e-mail to Shaw: “Each year after school has ended, students have been allowed to come to school and move furniture, paint, clean, and dust … . These students receive credit for having attended class, in some cases within a day or so of graduation. Virtually anyone can participate. If asked, the entire … faculty will provide statements documenting this.”

Six teachers, all of whom have asked for anonymity for fear of losing their jobs, said they witnessed the students in their clean-up routine. They also said that students earned “credits” by working the concession stands at athletic events and even by running errands for a coach and administrator.

If policies like that upset many teachers, they didn’t lessen the support Alexander received from many Heights parents and students.

Several parents of former students, who asked that their names not be used, praised her as a dedicated, “kid-oriented” principal who was always there to help their children through rough patches.

“My child made it through high school because of her,” one mother said.

A former student recalled Alexander as “always walking the halls, stopping to talk to us, asking how we’re doing, popping into our rooms. We knew she cared about us. We loved her.”

Faculty members who spoke to the Weekly agreed that the principal was kid-oriented — but not necessarily in ways that actually helped the students. Her willingness to let students off easy “was very disturbing,” a teacher said, “because it was a disservice to the students who were able to graduate without earning the credits, and it was unfair to the students who worked hard all year and earned their credits the right way. … We have now put kids out there without the tools they need to compete in the real world, whether they go on to college or work. How does that benefit them or society?”

Teachers and coaches said that Alexander had sent out an e-mail this year instructing them not to call the campus police officer or the Fort Worth police unless a student was clearly breaking the law, such as by selling drugs on campus. Fighting or attacking a teacher did not automatically qualify, they said.

Despite that, a Fort Worth Police Department spokeswoman said records show that from September 2009 through June 2010, officers responded to more than 80 incidents at Arlington Heights. They included seven fights between students, with some resulting in serious injuries and arrests, she said. Others included “violations of the penal code, assault, and drug use.”

Despite that, a Fort Worth Police Department spokeswoman said records show that from September 2009 through June 2010, officers responded to more than 80 incidents at Arlington Heights. They included seven fights between students, with some resulting in serious injuries and arrests, she said. Others included “violations of the penal code, assault, and drug use.”

One of the most violent fights involved 60 to 80 black and Hispanic students, said a coach who helped break it up. It was so out of control that the teachers who witnessed it called it a riot.

It was mid-April, the week of the TAKS test, and a large number of kids had been allowed to spend some down time outside because there had been so much intense studying for the test.

The fight started on the football field after a few racial slurs were directed at the Hispanic kids by some white kids, the coach said. The white kids disappeared from the fight, but it continued on the main campus, where the Hispanic kids were surrounded by African-American students who backed them up against a wall, witnesses said, and were pummeling them. The campus police had not been called; the only adults present were the coaches who were trying to break up the fight, one teacher said. It lasted about 15 minutes, and by the time the campus police were called, a number of kids were injured, some needing emergency care.

“We didn’t call the police right away,” one coach said, “because of Neta Alexander’s directive.”

Shortly after that fight, according to the complaint and interviews with faculty witnesses, two students were reported to have brought shotguns onto the campus in their cars, a “zero-tolerance” violation that, by district policy, should result in an automatic transfer to an alternative campus. The guns were seen by two students, who reported them to a faculty member. When the faculty member reported the information to Alexander and asked for permission to search the car, he said that the principal responded, “I know them. They’re doctors’ kids. We won’t search their car.”

The assistant principal, in his complaint to the district, later wrote that “student discipline was manipulated” that day to ensure that 13 of the students involved in the fight would miss the TAKS test. The students, who had been judged unlikely to pass the test, were at first suspended for nine days. Then, after the TAKS had been administered, he reported, six days of the suspension were forgiven, and the students’ status was changed from suspended to “excused absences.”

Another fight reportedly took place across the street from the school in the Central Market parking lot, witnessed by about 100 students. One kid, a basketball player, jumped a smaller kid and beat him so badly around the head that he needed 20 stitches. The attacker was not suspended or otherwise punished. The victim, who was a homeless student, had serious psychological problems following the attack, the teacher said. His whereabouts are now unknown.

Another fight reportedly took place across the street from the school in the Central Market parking lot, witnessed by about 100 students. One kid, a basketball player, jumped a smaller kid and beat him so badly around the head that he needed 20 stitches. The attacker was not suspended or otherwise punished. The victim, who was a homeless student, had serious psychological problems following the attack, the teacher said. His whereabouts are now unknown.

The assistant principal even had to break up two fights between staff members — going on as students watched.

In another gun-related incident described in the complaint, a teacher told colleagues he had seen a student passing a gun in a brown paper bag to a non-student who was not supposed to be on the campus. The teacher said he was ignored when he reported the incident to Alexander. And a teacher’s aide who “was assaulted [by a student] and called 911 [without first asking permission] was pressured by Ms. Alexander to resign” the complaint states.

One teacher said he “witnessed a student go berserk, throwing books, kicking over desks, threatening the teacher, and I told [an administrator] to call the police. He said, ‘Under no circumstances can I call police,’ ” citing Alexander’s directive. “The student had assaulted three teachers by then, and I yelled, ‘Can we call the cops now?’ ”

The teacher held the student for more than 15 minutes, he said, while they waited for an OK from Alexander, who finally let them call 911.

As for the unexploded bomb, Fort Worth police confirmed on Tuesday that they were called to the school on Oct. 14, 2008, in connection with that incident but that they could find no record of any arrest or follow-up action.

One of the strangest allegations of what’s been going on at Arlington Heights has to do with Perry, who until a few weeks ago was the school’s girls’ athletic coordinator.

In the complaint, a dozen teachers, coaches, and other staffers said Perry made a common practice of using vile curses and sexually explicit language with both students and other teachers, and thought nothing of describing her sex life in obscene terms and great detail to those around her.

She reportedly yelled at students to “get the fuck out of my gym” on numerous occasions. According to another volleyball coach who heard her, she once told male soccer players who were about to go to an out-of-town tournament, “not to have sex with each other, no butt-sex, no sex with animals, and no sex with girls.” Her boyfriend allegedly enlisted students to carry notes to Perry setting up their meetings and to run errands for him. He then wrote excused absences for those students for the classes they missed.

Staffers said Perry’s bullying and foul language were well-known to Alexander. One teacher said that when complaints were lodged with Alexander, the response was, “Oh that’s just how she is.” Or, “I’ve been trying to talk to her about her language for years, but she won’t listen.”

Some teachers saw the coach’s constant sexual references as a form of sexual harassment and her constant cursing and obscenities directed at students as child abuse.

“We felt she [Perry] was protected by the principal, and we were all afraid for our jobs if we complained,” one teacher said, in a comment echoed by others.

The assistant principal’s complaint alleges that Perry claimed to have protection from even higher up the chain of command, from a district administrator with whom she had once worked.

The teachers interviewed said Perry constantly bragged that the administrator was under her thumb and that she could do anything she wanted, even “get your job” because she knew so much about him that he wouldn’t want known.

According to documents filed with the complaint, Perry is alleged to have said on numerous occasions, to teachers in groups and individually, that the administrator was in her debt because she had let him borrow $5,000 from the school’s booster- club funds.

According to documents filed with the complaint, Perry is alleged to have said on numerous occasions, to teachers in groups and individually, that the administrator was in her debt because she had let him borrow $5,000 from the school’s booster- club funds.

Several teachers said this week that district investigators have questioned them about that alleged loan. If Perry indeed had access to the funds, that could in itself be a violation of district policy. Employees are forbidden to handle such funds, which come from donations, concession stand proceeds, and fund-raisers, and are to be used only to benefit students and athletes.

There have been a number of resignations over Perry’s behavior, the teachers said. One coach’s resignation statement, included in the complaint documents, reads, in part, “I cannot be part of an athletic program that is tainted by one uncontrolled individual any longer.”

Shortly before school was out this year and just as the investigation of the assistant principal’s charges got under way, Perry and the man she was dating both resigned, and Perry moved to another city.

She told the Weekly that she “has no plans to ever return to the Fort Worth school district.” She declined to comment on the investigation or the reason for her resignation.

For two years, the assistant principal who became one of the whistleblowers had received excellent reviews from Alexander. Once she even told him he was so dedicated to his job that he was showing up the other administrators and that he should “dumb down a little,” LaBeau said.

He’s dedicated to the school, LaBeau and Shaw both said, despite the treatment he has received and even despite receiving a death threat from a father of a student he had to discipline. The man also threatened to harm the assistant principal’s daughter, who attends Arlington Heights.

He’s dedicated to the school, LaBeau and Shaw both said, despite the treatment he has received and even despite receiving a death threat from a father of a student he had to discipline. The man also threatened to harm the assistant principal’s daughter, who attends Arlington Heights.

In March, however, when the assistant principal was named as the school district’s diversity representative, everything changed.

The diversity team is part of the district’s latest effort to reduce its lawsuit load by encouraging employees who know of rules being broken to come forward so that problems can be resolved before they reach the courthouse.

As he’d been instructed, the assistant principal wrote in the complaint, he held diversity-training workshops for employees and encouraged them to come forward with any knowledge of problems like hostile work environments, sexual harassment, or other violations of law. He was told to forward all employee complaints to the district’s diversity representative, Sharon Herrera, for action. Employees were assured in memos from Johnson and Herrera that there would be no retaliation for coming forward, the complaint states.

Soon after the training session, according to the documents, the assistant principal began receiving dozens of complaints from employees, most relating to falsified attendance records and a hostile work environment. One worker called the school a “cesspool,” while another charged that a “culture of fear” permeated the halls of Arlington Heights.

From April through May, the complaint documents show, the assistant principal reported the allegations of wrongdoing to Herrera, who sent them to the district’s chief investigator in the Office of Professional Standards, Mike Menchaca. A few weeks later, on June 22, assistant superintendents Chuck Boyd and Robert Ray confronted him and told him he was being transferred to the International Newcomers Academy, a grades 6-9 school for new kids in the district who speak little or no English.

According to the complaint, Boyd and Ray told him he was being reassigned because of a poor evaluation from Alexander, even though he had no prior warning and all of his other evaluations from her had praised him as a skilled administrator. Suddenly he had dropped from “exceeds expectations” to “needs improvement.”

Boyd returned one phone call from the Weekly while on vacation and promised to call back later concerning the allegations. He has not responded to several follow-up calls and e-mails.

The assistant principal saw the transfer as a demotion — going from a high school position to an alternative middle school where the hours would be much shorter and his pay therefore would be cut, LaBeau and Shaw said. Not only would the transfer affect his life, it would affect his daughter’s as well: He lives outside the city but by virtue of his work at Arlington Heights was allowed to enroll her there. She is a sophomore honors student and had been a volleyball player until the coach’s language became intolerable.

He refused the transfer and immediately filed the complaint against the district.

“I cannot imagine what the administration is thinking,” said LaBeau, who ran for the school board this year, losing to Needham. Her clients include students, educators, and parents involved in education-related disputes.

The assistant principal “is the very kind of man you want in his position, especially at a school like Heights where many of the kids are from broken homes, single-parent homes, and they need just such a role model,” she said. “He’s ethical, firm but fair, cares deeply for kids, and is honest to a fault. They should have been promoting him instead of trying to shut him up.”

Shaw, whose organization does not normally take up management disputes, said he was approached by 25 Heights teachers, all members of UEA, who asked him to take the case. “When it was all laid out, I thought this guy had gotten a really raw deal, so we agreed that the right thing to do was to work to get him his job back,” Shaw said. “He is a straight-arrow guy, a retired military man who did exactly what he was told to do by the district and got demoted for it. Incredible.”

The transfer was upsetting to the whistleblower. But its repercussions could turn out to be even more painful for district officials who participated in it.

As it turns out, the district may have violated some of its own rules in forcibly reassigning the assistant principal.

In the complaint, the assistant principal stated that he received the negative evaluation by e-mail on June 21, the day before Boyd and Ray cited it as the reason for his transfer. That e-mail in itself is a problem. District policy requires negative evaluations to be delivered face to face, according to LaBeau.

Another question was raised by the timing of the e-mail. According to the complaint, the evaluation was allegedly signed by Alexander on June 19.

However, other information has come to light calling that date into question.

On June 22, the same day that Boyd and Ray were delivering news of the transfer to the assistant principal, school board members also heard about it, as part of a list of appointments to be made for the 2010-11 school year. The list, provided in the package of material for the board’s regular meeting that night, showed that the transfer decision had been approved by Johnson on June 18 — the day before the poor evaluation was supposedly written.

What’s more, the document provided to the school board said that the transfer was being made because the assistant principal was “very organized and hard working” — hardly an indication that he “needs improvement.”

District officials have since backed off that decision, but not in any way that is reassuring to the assistant principal. Last week, Shaw was informed that his client’s transfer to the newcomer school had been withdrawn and that he was being moved instead to Western Hills High School as assistant principal.

“The school’s principal had no idea he was coming, told him he had no need for him, and in fact the district is having to hastily build an office for him and order a computer since there was no office or equipment for an extra administrator at Western Hills” LaBeau said. Despite that, she said, the principal at Western Hills told his surprised new recruit he was “glad to have the extra help.”

“My client will not settle this complaint for anything less than an apology [and] his return to Heights with his position as assistant principal restored,” LaBeau said. “But while [the complaint] works its way through the administrative process, he is going to report where [the administration] sends him, no matter how obvious it is that they are bent on keeping him out of Heights at all cost, no matter how ridiculous it gets, or how much it costs the taxpayers.”

If the district rules against him, LaBeau said, he intends to file a whistleblower lawsuit in federal court. If that happens, it will be the second suit filed against the district this year by an employee claiming retaliation for reporting some inconvenient truths. A former payroll department worker sued after she was fired following her warnings to the administration that a new and complicated computer payroll system was being rushed into place before it was ready. When the new system was fired up, it was a disaster, just as the fired worker had predicted.

LaBeau said the assistant principal considers his stand a matter of honor: “He was doing what he was charged to do, and he made promises to the teachers that there would be no retaliation if they spoke up. Then he was suddenly the victim of retaliation, and he knew that it struck fear into the hearts of the teachers who had come forward. If it could happen to him, how safe were they?”

The situation at Arlington Heights clearly has many district officials worried.

“I have never seen [allegations of wrongdoing] as large as this at any high school,” said Rangel.

The trustee is also unhappy about that other transfer — of Alexander, to fill the vacant post of principal at R. L. Paschal High School, one of the city’s best-performing schools. (Jason Oliver, a former middle school principal, will take the helm at Arlington Heights when classes start on Aug. 23.)

Paschal is in Rangel’s district, and if he has anything to do with it, Alexander’s posting there may be short-lived.

“I have asked Dr. Johnson to reconsider this appointment until the results of this investigation are known,” he said. “Mrs. Alexander brings too much baggage with her now. … It is simply not fair to have this uncertainty hanging over the heads of the Paschal students and teachers.

“There are too many unknowns in this,” Rangel said. “One wonders if something is going on behind the scenes that the board is not being told. We need to look carefully at the timelines. … How do they reveal the real series of events that happened? Who knew what and when, and how far up does this reach?”

[…] former attorney Jason Smith could not be reached for comment.The saga of Palazzolo started in 2010, when he went to administrators with teacher complaints about attendance fraud, disparate treatment […]