On a cold, dreary January afternoon, somewhere amid a neat row of bunker-esque buildings in an industrial area near Six Flags in Arlington, a man was standing in a doorway aggressively rapping over what sounded like the soundtrack to a child’s nightmare. Upon closer inspection of the makeshift lobby area of the Universal Rehearsal Arlington studios, the dude spitting hot fire was being accompanied by a man hammering down on what was either a broken or badly out-of-tune piano and another guy banging drumsticks on the back of a derelict fabric couch like he was playing out his Blue Man Group fantasy.

Farther inside, the converted office building was a maze of barren hallways with all the charm of a U-Haul storage complex. Countless styles of music spanning every skill level bled out from behind many of the dozens of cell-like doors. Pot smoke hung in the air so thick you could have sliced it like a Bundt cake –– and that was the least offensive scent among the space’s olfactory buffet.

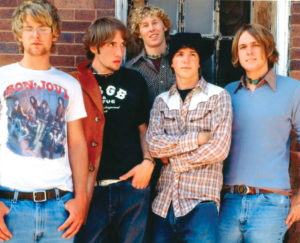

Behind a nondescript door at the end of the maze was Green River Ordinance’s rehearsal space. Compared to other tiny rooms, it was like stepping through a wardrobe into Narnia. The Fort Worth-based five-piece seemed out of place compared to the David Lynch movie happening on the other side of the door. The guys are uncommonly nice and polite, down-to-earth, and quick to laugh. There’s something even wholesome about their demeanor –– it’s as if all of the cool church youth group counselors got together to play music.

The band launched into “Tallahassee,” a twangy, anthemic, harmony-heavy tune from GRO’s recently released ninth album, Fifteen. Drummer Denton Hunker activated programmed lights that penetrated the haze generated by a machine in the corner. The heat from the light show raised the temperature in the room to the point that the band members looked as if they just finished a rec-league basketball game.

“The lights are triggered by the drums,” said Joshua Wilkerson, the band’s keyboardist/mandolinist/guitarist. “We have to make sure they work.”

The quintet was practicing for last weekend’s gig at the Sundance Film Festival –– both Hunker and singer/guitarist Josh Jenkins were wearing matching snow boots that festival organizers gave out to performers as swag.

Anyone who hasn’t heard these guys in awhile might not recognize them. All of the tunes GRO played that day had a distinctly Southern lilt. The songs on the new record represent a significant departure from the band’s early stuff. Though it happened gradually, the sonic shift is the product of the natural maturation of a group of guys in their early 30s who have been playing together for 15 years –– or for all of their adult lives.

The twang is also an expression of freedom from their former bosses. When the band was signed to Capitol Records, the label execs wouldn’t let the musicians explore their Southern roots. But thanks to a major error by the record company’s legal department, the band was able to walk away and chart their own sonic path.

“When you look at what you listened to in high school versus what you listen to today, it’s very different,” said guitarist Jamey Ice, whose shaggy blonde rock ’n’ roll hair belies his almost-permanent grin and easygoing charisma. “When I was in high school, I only liked rock. I remember telling my dad I thought James Taylor was so lame. And now when I get home, all I want to do is put on James Taylor and relax.”

Despite being so young, the GRO boys have packed a lifetime’s worth of experience into their decade-and-a-half run. They’ve dealt with stolen money, a bankrupt record label, a struggle with that label over creative control, debt, and balancing family life with rock ’n’ roll.

For a group that started life as pop-rock band in the Matchbox 20 mold and experienced so much success and adversity early on in their careers, the quintet has stayed remarkably relevant. The band still sells out shows, gets regular airtime on terrestrial radio and thousands of plays every day on streaming apps and YouTube.

The guys have grown up together, learning how to be a band –– on-and offstage –– along the way. Though all of them have had odd jobs here and there, being in a successful road act has been the only career any of them has ever known.

“We’re pretty lucky,” said bassist Geoff Ice, Jamey’s younger brother. “I don’t think at any other point in our lives would we have been able to just drop everything and become such road warriors. We didn’t have any other responsibilities.”

******

After dropping out of college to do the band thing full time in 2006, the guys from Green River Ordinance did what a lot of young upstarts do, explained Jamey.

“It’s kind of a reckless thing,” he said. “We’re going to get a credit card, we’re going to buy a van, and go on tour. We lived off credit card debt that we probably didn’t pay back for five or six years. I don’t think I would tell my kids to do that, but it was a really cool time.”

At the time, the guys were in their early 20s and had already self-released a full-length album and an EP. Four of the five members were split between Texas Christian University and the University of North Texas respectively, and Jamey and Geoff’s parents told them they could leave college to tour for one year. If they didn’t get a record deal by the end of that time, they’d have to go back to school.

Life on the road was a hand-to-mouth existence –– each band member lived on a self-imposed $100-per-month stipend –– but Jenkins said it was a fun experience, even if the money wasn’t rolling in the way they’d hoped it would.

“It was the great wide open,” he said. “It was an adventure. The fact that we had no money and didn’t know where we were staying was exciting.

“I remember we printed off sheets from MapQuest to find the venues,” he said. “If you missed a turn, you were completely screwed. We’d play a show for nobody and rolled through the night to another city because we had a gig, and have to find a hotel, and they kicked us out because there were too many people in the room.

“Fun little stuff like that makes the adventure,” he said.

Things changed dramatically for the band when they were singed to Capitol Records in 2007 and released the album Out of My Hands the following year.

“We were out on the road 312 days a year,” Jenkins said. “And then the next year, we were gone about 290 [days], then 270.”

******

Great article about my favorite band! Loved hearing their whole story!