It’s common as pork on a pig for members of Congress to lobby for Corps-performed flood-control projects — everybody’s district has a waterway or two that’s prone to flooding, and the competition is always fierce. In November 2004, when Granger got congressional OK for the Corps to spend serious money on the Fort Worth project, there were more than 200 projects, with a combined price tag of more than $60 billion already waiting in line for money. Some of these projects had been on the books for decades — with all their studies completed and every “i” dotted and “t” crossed.

It’s common as pork on a pig for members of Congress to lobby for Corps-performed flood-control projects — everybody’s district has a waterway or two that’s prone to flooding, and the competition is always fierce. In November 2004, when Granger got congressional OK for the Corps to spend serious money on the Fort Worth project, there were more than 200 projects, with a combined price tag of more than $60 billion already waiting in line for money. Some of these projects had been on the books for decades — with all their studies completed and every “i” dotted and “t” crossed.

Like the Trinity River project itself, Granger’s success relied on a bypass channel, by which she carried water for the project around by a back way.

Corps of Engineers projects are supposed to be approved by the House Subcommittee on Water Resources and the Environment, which is part of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. The subcommittee recommends flood- control projects under the auspices of the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA), giving preference to those that have good science behind them — and usually, heavy political backing.

But the panel hasn’t approved money for a WRDA project since 2000. The reasons: Bush administration cuts to the Corps budget and an overload of pork barrel projects with little flood-control work to them. In fact, the House and the Senate tried to pass a WRDA bill in the past month during the lame duck session of Congress, but it never even came up for a vote because members had crammed it so full of projects (about $15 billion worth) that they knew it would get shot down by the White House.

But that doesn’t mean that no new Army Corps of Engineers projects have been funded in the last six years. Levee construction to repair the damage from Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans was funded through emergency bills that bypassed formal hearings. Still, many parts of the country are waiting for badly needed — and fully authorized — projects to be funded. Gulf Coast restoration projects have been put on hold. A $1.2 billion South Florida Everglades restoration project that environmentalists have been pushing for years is still in limbo. So is a controversial $3.8 billion plan that would mix environmental cleanup with new locks and dams on the upper Mississippi and Illinois rivers.

So how did Granger move Trinity River Vision funding past the logjam so quickly? She did it by putting the money in an “earmark” bill that was handled by the Appropriations Committee, where — for a few more weeks — she is a high-ranking “majority” member. Earmarks are ways to get bills passed without any discussion or debate. They may be added on to big spending bills (Congress is famous for adding some local road project at the end of a military spending bill) or thrown in with a random group of funding issues. In this case, Granger stuck the Trinity money in with projects backed by other well-connected Appropriations members who also wanted to bypass the usual rules.

The earmark bill contained a few other Corps projects — harbor dredging in Indiana and Alaska, a $25 million improvement of a watershed near Lake Tahoe in California, and cleaning up a waste- water treatment center in Wisconsin. But none came close to the $110 million allocated for Trinity River Vision — tucked away amid the fine print of a bill dealing with “Foreign Operations, Export Financing and Related Programs.”

There are several ways to look at Granger’s use of her place on the powerful Appropriations Committee to make an end run around the transportation committee. She was using her political clout to push through a project that could have huge economic development benefits (not mentioning the considerable economic costs to certain businesses and neighborhoods). And even though Republicans love to rail against earmarked bills, they see them as a useful tool when pushing their own agendas.

Granger’s response is that she was just being practical. In an e-mail, her spokeswoman, Caitlin Carroll, said Granger had tried to get the project authorized via a WRDA bill in 2004, “but the Senate and the House couldn’t come to an agreement on the final bill. Therefore, in order to move forward with the project, we had to look at other options to get the project authorized.”

Appropriations was the only way, she said. “We just had to be practical.”

Democrats who had to watch these projects being funded ahead of theirs had no way to stop them at the time. But times have changed.

Congress has complicated rules, and there are exceptions to those rules — and exceptions to the exceptions. But there is some debate as to whether the Corps’ funding for Trinity River Vision was ever formally authorized. Under House rules, the Appropriations Committee approves funds for projects that have already been given the nod by other committees. What it boils down to is that, no matter what the originating committee approves, the appropriations panel can change the funding or cut it altogether.

By starting the process with Appropriations, Granger pushed through the Trinity River Vision funding much faster, but she also may have left it open to attack. Because of her end run, the TRV money will have to be approved in annual $10 million “add-ons” to the budget bill. So each year, the project will have to survive another vote.

If the Republicans still controlled Congress, Granger would have nothing to worry about. But with the Democrats taking control next month, the ground rules have changed. Democrats see their election as a mandate to reduce the budget deficit, rid the country of “earmark” projects (or at least the ones that don’t benefit them), and maybe pass out a little punishment to the party that’s been lording it over them since 1994.

If you think the Trinity River Vision’s money is already safely doled out and set aside, think again. One need go no further than Dallas to find a powerful member of Congress who says the project needs more scrutiny. U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, a Democrat who will chair the House Subcommittee on Water Resources and the Environment next session, said that projects like the Trinity River Vision may be closely looked at by the new Congress because of “issues of fairness.”

If you think the Trinity River Vision’s money is already safely doled out and set aside, think again. One need go no further than Dallas to find a powerful member of Congress who says the project needs more scrutiny. U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, a Democrat who will chair the House Subcommittee on Water Resources and the Environment next session, said that projects like the Trinity River Vision may be closely looked at by the new Congress because of “issues of fairness.”

“Our committee does the authorization of Army Corps of Engineers flood-control projects, and I can tell you this — we have never even heard of the Fort Worth project,” Johnson said. “We have never even heard about the $110 million.”

Because the committee hasn’t passed a water development funding bill since 2000, “that has put pressure on some members to use creative ways to get their projects passed. They sneak them through the back door,” Johnson continued. “But at the same time, members who have noteworthy projects have been battling through the process under the rules of order. It becomes a fairness issue, and I’m sure this Congress will be addressing that.”

Still think it’s impossible for a project with this much backing from local powers-that-be to get killed off in the budgeting process? Look no further than the Waxahachie area, where the much-ballyhooed Superconducting Super Collider project died after the federal government spent millions buying land and homes in the area — including some from people who didn’t want to sell — for the huge underground testing chamber. Johnson pointed out that the reason the Super Collider was able to be killed so quickly in 1993 was that its funding had originated in Appropriations and was never formally authorized by a standing committee with jurisdiction.

Still think it’s impossible for a project with this much backing from local powers-that-be to get killed off in the budgeting process? Look no further than the Waxahachie area, where the much-ballyhooed Superconducting Super Collider project died after the federal government spent millions buying land and homes in the area — including some from people who didn’t want to sell — for the huge underground testing chamber. Johnson pointed out that the reason the Super Collider was able to be killed so quickly in 1993 was that its funding had originated in Appropriations and was never formally authorized by a standing committee with jurisdiction.

“Our mandate on Army Corps of Engineer funding is that it can be used for economic development, provided the flood control is used to protect existing housing and businesses,” Johnson said. “This comes from the Corps and the Bush administration and are the rules by which we study these projects in Congress. We have people on the committee who do their homework, and I don’t think they would buy [the idea] that [Trinity River Vision] meets some basic requirements. From what I know of the Fort Worth project, it really doesn’t have a focus on saving existing businesses and life and housing. I would have to say it wouldn’t have had much of a chance if it came through our subcommittee.”

Steve Ellis, vice president of programs for Taxpayers for Common Sense, a Washington-based watchdog group, said Granger’s way of getting funding through the Appropriations Committee is an “extraordinary way of doing things.” He’s studied the Corps’ funding issues. “We see a lot of earmarks pushed through, but they are usually not this big, and usually the funding isn’t approved before something like an environmental impact study is done,” he said. “It is an example of the breakdown of the process and not even close to the normal way of doing things in Congress.”

Besides potential problems with Johnson’s subcommittee and the Democrats, the TRV project may find its way hampered in the future by the growing outcry — from both sides of the aisle — against abuse of eminent domain, especially on federal projects. Many members of Congress want to see new limits placed on government’s ability to take land from those who don’t want to sell.

And if Congress does pass another water development funding bill next year, as expected, it could include a requirement that all Corps flood-control projects over $40 million be subjected to an independent, though non-binding, review.

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, in devastating so much of the Gulf Coast, may also have eaten part of the foundation out from under the TRV. A lack of maintenance and investment in the levees was pinpointed as a major cause for the flooding of New Orleans, and criticism has specifically targeted the Corps’ use of its limited funding on optional, economic development-oriented projects, rather than basic flood protection.

Political tea leaves are always tricky to read, but one thing seems clear: Those who oppose the Trinity River Vision project, many of whom thought they’d lost their battle, are perking up their ears again. They realize they may be able to find folks in Congress willing to listen to their objections, after all — just not the folks who represent their own district.

Political tea leaves are always tricky to read, but one thing seems clear: Those who oppose the Trinity River Vision project, many of whom thought they’d lost their battle, are perking up their ears again. They realize they may be able to find folks in Congress willing to listen to their objections, after all — just not the folks who represent their own district.

Former Fort Worth city council member Clyde Picht ran for the Tarrant Regional Water District board this year and lost. He opposes the Trinity River Vision as a conservative, believing that public money should not be used as an economic development tool that will force 95 property owners on Fort Worth’s North Side to sell their property through eminent domain. Picht may be running for council again next year specifically to work against the project. Picht and other TRV critics said they’re tired of trying to make their case to local politicians and will be taking the argument directly to Washington.

“There has never been any real public input on this project, and any time we raise issues, we are ignored,” Picht said. “We will be taking it to Congress and have identified some key players. This whole process has been done with total disregard for the voting public. It is a city project, handled by the local water district, and in no way should it be a federal project. If Fort Worth wants to do this, and pay for it all, it should go before the public in a vote.”

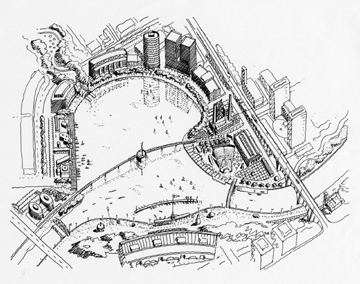

Picht acknowledged that a successful lobbying effort in Congress will be difficult. But he said the message will be how the project has changed mightily from its beginnings. The initial Corps study of the Tarrant part of the Trinity recommended spending $9 million to increase the flood-control capacity of current levees. Over time, that modest plan has grown to include a lake and canals and the bypass channel, costing $435 million at last estimate. Half of that would be in federal funding — the $110 million from the Army Corps of Engineers, plus another $100 million from the EPA, the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, and the U.S Dept of Transportation. The project has received several small federal grants but still needs approval on the majority of the funding.

Picht acknowledged that a successful lobbying effort in Congress will be difficult. But he said the message will be how the project has changed mightily from its beginnings. The initial Corps study of the Tarrant part of the Trinity recommended spending $9 million to increase the flood-control capacity of current levees. Over time, that modest plan has grown to include a lake and canals and the bypass channel, costing $435 million at last estimate. Half of that would be in federal funding — the $110 million from the Army Corps of Engineers, plus another $100 million from the EPA, the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, and the U.S Dept of Transportation. The project has received several small federal grants but still needs approval on the majority of the funding.

A coalition that opposes the project, Citizens Who Care, has come up with an alternative plan that would cost just $43 million. It calls for improving flood control via levee work and would create a lake without the bypass channel, canals, and all the costs of rerouting the river. The Corps’ part of the funding for this alternative would be about $31 million.

Picht and several others said they will present that plan to members of Congress, especially those from areas devastated by Gulf Coast hurricanes in recent years and those opposed to eminent domain. Picht wouldn’t name the specific targets of the lobby effort, but several Democrats, in addition to Johnson, seem likely to be on the list: Peter Visclosky of Indiana, who serves on Appropriations and has worked to reform Corps’ spending; David Obey of Wisconsin, likely to be the new chair of Appropriations; Charlie Melancon of Louisiana, a possible appointee to Appropriations who has worked to get flood-control money for Louisiana; and Mississippi’s Bennie G. Thompson, new chair of the Homeland Security Committee and an activist in flood-control spending in his state.

Lobbying Congress “has crossed our mind, yeah,” said Bob Lukeman, whose photography studio would be taken through eminent domain. “There is so much going on right now, and you can see that [Trinity River Vision supporters] are focusing on protecting their interests in Washington. They have kept the debate quiet here in Fort Worth, with the spin being that we all like it. The funding has been hidden from Congress.”

Pork-barreling. Eminent domain concerns. End runs to get funding. Corps of Engineers spending priorities. Democrats out to get back some of their own. The list is long enough to give Fort Worth folks cause to question how secure the TRV’s future is. And then there are what some consider self-inflicted wounds — political moves that may have dug some holes in the Trinity River Vision’s credibility.

When Kay Granger’s son, J.D., a former prosecutor in the Tarrant County DA’s office, was named executive director of the project earlier this year, at a salary of $110,000, many were appalled at what looked like blatant nepotism. The younger Granger had no experience in any kind of project like this, but Tarrant Regional Water District General Manager Jim Oliver defended the hire, noting that J.D. had been involved in the project at various levels for years. The recent appointment of a separate Trinity River Vision Authority board has also raised some ire, as almost all members of the new board are elected officials or high-ranking government workers who have a vested interest in the project. The only person on the board who’s not already in government — Elaine Petrus — is a longtime Kay Granger backer.

Eyebrows went up again last month at the announcement that the TRV board had awarded two five-year public relations contracts worth $1.6 million to political consultant Bryan Eppstein. He’s known for his work on political campaigns, particularly in telephone polling and examination of voter lists — for clients like Granger, Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief, most current Fort Worth City Council members, and the two most recently elected members of the Tarrant Water District board, Marty Leonard and former Fort Worth City Council member Jim Lane, both of whom support the Trinity River Vision project.

Despite the fact that Eppstein’s group is supposed to be handling public relations for the project, the firm’s point man on TRV, Jay Pritchard, did not return any of several phone calls from Fort Worth Weekly seeking comment for this story. Thus interviews with J.D. Granger and Bryan Eppstein were not made available.

“This is an inside job” wrote Fort Worth Business Press publisher Richard Connor, who usually sides with projects supported by the downtown business interests. “Eppstein manages campaigns for political candidates who pay him at least twice — once when they run, and again after they get elected. It’s a conflict, but the officeholders are more beholden to Eppstein than they are to you, the voters.”

Mike Wilie, president of Witherspoon Advertising and Public Relations, a Fort Worth firm that has been in business for 60 years, was particularly disturbed by Eppstein’s contract. “There are a number of issues that raise a red flag,” Wilie said. “They didn’t talk to anyone, no interviews with any other firms, no bids. The other problem is the length of the contract. Whenever we have done work for government groups, we get one-year contracts, because things can change quickly in a short period of time. For Eppstein to get five years is something that is never done. If that is an example of how they do business, then they have a lot of problems.

“Some of the business people I’ve talked to say the way they handled this is making this whole project a big issue,” Wilie continued. “Hiring a public relations firm is about improving the image. In this case, they [Eppstein’s group] have caused problems. But maybe they pushed this through because they foresee big problems in Congress. That’s the only reason I can see.”

If recent developments have opened cracks in the TRV façade, they haven’t come close to knocking it down. Observers figure Granger will still have plenty of power to protect her favorite project. The shift in power in Washington, they said, doesn’t automatically wipe out the relationships she has built on the Appropriations Committee. But some of her other political relationships may come back to haunt her.

“There is an interrelationship between the Appropriations member, and sometimes party plays into it, sometimes it doesn’t,” said Matt Angle, director of the Washington-based Lone Star Project, a group that advocates for Texas Democrat political issues. “There are a lot of favors and trading that go on with that committee, and sometimes members of the different parties have to work with each other to protect their own interests.”

But Congress is going to be under pressure to reduce the massive federal deficit that has piled up in recent years, and the TRV project “is certainly the type of project that could be at risk,” Angle said. “It’s not competing with Katrina spending, but with other similar projects earmarked around the country. … Congress will be looking at all these earmarked special projects that were passed in the old Congress.”

Former U.S. Rep. Martin Frost, who now runs a political consultancy group in Washington, agreed that Granger’s Appropriations Committee membership will make it harder to stop Trinity River Vision. “It depends on Kay Granger’s relationships with individual members of Congress,” Frost said. “At home, she likes to portray herself as a moderate who works well with all sides in Washington. But she is seen by Democrats as a hard-shell conservative who is an enabler for every Republican issue. She has voted with [former Texas U.S. Rep. Tom] DeLay on everything, and that doesn’t make for any natural allies on the Democratic side.”

Frost thinks Granger may have an ace in the hole. Veteran Democratic Congressman Chet Edwards of Waco, whose re-drawn district now runs into southern Tarrant County, will basically be taking Granger’s former role on Appropriations as a high-ranking majority member from Texas. He has been supportive of Trinity River Vision. “Chet Edwards will be the go-to guy,” Frost said — but since the TRV isn’t actually in his district, his support may not be as strong as Granger’s.

Edwards, who was undergoing surgery on his larynx this week, wasn’t available for comment. His spokesman John Taylor said in an e-mail that Edwards “has a tradition of working … in a bipartisan manner to fund important projects such as the Trinity River project.”

But the difficulty in Edwards taking a lead role for a project outside of the district was apparent in Taylor’s e-mail. He included six attachments regarding spending on Trinity flood-control projects — and five were about the Dallas Floodway Extension, Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson’s pet project. Trinity River Vision merited only three short sentences.

Don Woodard Sr. often calls the Trinity River Vision project a “bridge to nowhere.” The insurance executive, who has longtime ties to local Democrats, is referring sarcastically to a proposed $320 million bridge in Alaska to link the mainland to an island with 50 people. The funding got killed this year, as Congress reacted to the mockery and anger that ensued over this sample of earmark spending dumped into a big highway funding bill.

The Trinity project “is a bridge to nowhere,” Woodard said. “It will have bridges that take people to expensive condominiums and high-priced restaurants. I think most of the taxpayers in Fort Worth see it as a place that is nowhere they’ll be going.”

The Trinity River Vision plan is not necessarily a bridge to nowhere. It could make the river more accessible, create new economic development for the near North Side — and maybe even improve flood control in Fort Worth. But it could be a bridge with shaky foundations.

U.S. Sen. John McCain, a likely Republican presidential candidate, said recently that about 4,000 earmarked bills were passed in 1994, compared to an estimated 15,000 last year. In the same time period, total spending on these bills rose from $24 billion to $47 billion — all this under the Republican-controlled Congress that likes to talk about limiting government spending. He has called such spending obscene and disgraceful.

There’s no guarantee that the Democrats — usually portrayed as the big spenders — will have any luck in what new House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said will be a renewed effort to curb the budget deficit. But there’s no doubt the numbers are getting daunting. The annual federal budget deficit for fiscal 2007 is expected to reach $286 billion to $339 billion, depending on which government study you read.

The Corps of Engineers has been dealing with shrinking budgets for years — its funding for new construction projects is only about a quarter of what it was in the 1970s. The Bush Administration has made major cuts, shrinking the agency’s budget from $8.23 billion in fiscal 2006 to a planned $4.73 billion in 2007 — a reduction of more than 42 percent in just one year.

Johnson, the Dallas congresswoman, said the budget cuts “will have everyone trying to protect their projects” and that those that have gone through the normal budget process might have an advantage over those funded through earmarks. “There is going to be great competition, and since [Trinity River Vision] has never been discussed with me, the Trinity River Floodway Extension in Dallas would be my priority to keep,” she said.

Though Trinity River Vision and the Dallas Floodway Extension are separate projects, there may be some competition between the two. Both come out of the same Corps district office, and the argument can be made that, with money so tight, the Corps should not be doing two huge flood-control projects just 30 miles apart. And even though the Dallas Floodway Extension is considered by many to be a boondoggle in its own right — with a $1.7 billion total price tag, including $140 million in Corps funding — that project is much further along. The plans began to be developed in 1965, and Dallas voters approved a $246 million bond issue in 1998. The project was also authorized in the 2000 WRDA funding bill.

So the issues are fairly simple on a very complicated project. Will this evolve into another Dallas vs. Fort Worth struggle? And will Kay Granger abort other needed projects to keep her pet project going? Is Chet Edwards in the mood to do some heavy lifting on a project that isn’t even in his district?

For Picht and the others looking to take their message to Washington, timing is the key. The City of Fort Worth wants to start bridge construction in about two years, with another year and a half for construction. Only after the bridges are finished will the work on the river begin — the bypass channel and floodgates for the 33-acre lake. Congress would be more likely to kill a project where dirt for the new channel has not been turned, less likely if the water has begun flowing.

“I think we can present a good alternative that costs one-tenth of what they want to do, keeps some of the same access to the river they propose, and lets private economic development pay for most of the costs,” Picht said. “From everything I read about Congress these days, with their lobbying scandals and budget deficits, I would think this is what they might want to hear. I guess we’ll see if they are serious about all the changes they say they want to make.”

You can reach Dan McGraw at dan.mcgraw@fwweekly.com.