Payne’s song describes his mother late in life on one of her final road trips.

Payne’s song describes his mother late in life on one of her final road trips.

Mama, drive on / find your soul once again

Mama drive on / give those old wings a try

It’s one of several pearls on The Drifter, a vastly under-promoted and overlooked major-label album from 2004. Payne recorded the collection of original songs while living in Los Angeles; during that project he made connections that led to his first movie role, portraying Jerry Lee Lewis in the Academy Award-winning Walk the Line. When the movie premiered in 2005, moviegoers and critics noted his scene-stealing performance, and independent movie producers came dangling offers, including the lead in Crazy, about legendary 1950s Nashville guitarist Hank Garland. Crazy and four other movies are in the can awaiting release, most of them featuring Payne in supporting roles, including, he said, a “sick, delicious” horror movie called The Tripper.

“There’s about to be a whole bunch of Waylon around if those things ever come out,” he said.

Television beckons as well, and Payne finds himself in the enviable position of weighing options. He’s about to take the proverbial Hollywood High Dive, in which newcomers execute perfect half-gainers and swim effortlessly with the swans or go splat because somebody drained the pool on ’em in mid-air. Payne is unpredictable. He might just climb back down the diving board, get in his Benz, and leave Hollywood in the rearview.

Music stirs him most. His song “Lewis Boogie” was included on the Walk the Line soundtrack that went platinum. Pat Green, Charlie Robison, Shelby Lynne, and others have recorded his songs. “Her,” the gorgeous opening track on The Drifter, is gaining recognition — Django Walker had a regional hit with it in 2006, and Lee Ann Womack recently recorded the song for national release. Meanwhile, Payne is working on a second album with Fort Worth native Stephen Bruton as producer.

Most people would salivate at the idea of standing so close to fame and fortune. Payne is grateful, but he’s wary … of Hollywood, Nashville, celebrity, relationships, drugs, and himself. His career is poised to explode — unless he implodes first.

When he’s not in Tinseltown or Music City, Payne often holes up in a much humbler place — Roy and Sylvia Stamps’ comfortable two-story house between Mansfield and Venus. Roy Stamps was a radio deejay, music promoter, and co-founder of the original Texas Music magazine in the 1970s. For years, Smith, Willie Nelson, Mickey Newbury, and countless other songwriters used the house as a haven to catch their breath when in the area.

“It’s a great place to make music,” Payne said. “Peaceful, peaceful. Wind chimes going. Sweet tea in the fridge.”

Peace is a rare visitor in Payne’s world. He’s go-go-go and gone in a cloud of dust, which makes for great legend but also leaves people choking on the exhaust. “He’s good as gold, but he’s squirrelly — just like his mama,” said Stamps, who has much affection for both.

In early December, Payne drove in from Nashville to sing with Womack at Billy Bob’s Texas at a 95.9 The Wolf show but was instead asked to leave the club after a backstage incident. He stuck around town, though, and spent the better part of two days driving North Texas back roads and talking with me, explaining and exploring his mind and dropping bombshells, some for publication, some not. He comes across as a mythical character, vastly talented and vastly capable of self-sabotage.

In early December, Payne drove in from Nashville to sing with Womack at Billy Bob’s Texas at a 95.9 The Wolf show but was instead asked to leave the club after a backstage incident. He stuck around town, though, and spent the better part of two days driving North Texas back roads and talking with me, explaining and exploring his mind and dropping bombshells, some for publication, some not. He comes across as a mythical character, vastly talented and vastly capable of self-sabotage.

She hit the dirt road and pointed it west

She flew straight through Oklahoma …

Behind the wheel, Payne is focused and comfortable. His forearm rests on the steering wheel, revealing a tattooed portrait of Smith in her prime, when her smoky voice and sultry appearance enlivened Kris Kristofferson’s lyrics about a tryst. Payne’s song depicts a woman in a different stage of life, someone seeking deliverance.

Sunshine and raindrops through the roof hit her face

Gas up and freshen her joy around El Paso…

Mama drive on

I’m about to ask him what he meant by “freshen her joy” when he reaches over and flips open the glove box, snatches a bottle of perfume, spritzes a flowery scent above the dashboard, and whisks it with his hand.

“It was hers,” he says.

The perfume is labeled “Joy.”

The fragrance enhances memories of the mother he buried but hasn’t yet put to rest. Since her funeral in February 2005, he’s driven thousands of miles coast to coast, ended a destructive relationship, and curbed a fondness for whiskey and methamphetamine with a softer diet of lattes and weed. But he’s off-kilter and misses his favorite sounding board.

The fragrance enhances memories of the mother he buried but hasn’t yet put to rest. Since her funeral in February 2005, he’s driven thousands of miles coast to coast, ended a destructive relationship, and curbed a fondness for whiskey and methamphetamine with a softer diet of lattes and weed. But he’s off-kilter and misses his favorite sounding board.

“You’re catching me at a bad time,” he said. “Life has changed so much since she left. That was my one person … .”

Sammi Smith was just becoming famous when she gave birth on April 5, 1972, in Nashville. Her husband, Jody Payne, longtime guitarist with Willie Nelson, wasn’t around much, and the marriage was skidding. She named her son after his godfather, Waylon Jennings. Then she hit the road.

“At the time of my birth, ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’ had just hit number one,” Payne said.

The song, written by Kristofferson, crossed over and hit No. 8 on the Billboard pop chart, earned Smith a Grammy for best female country vocalist, and helped propel Kristofferson to fame by earning him a songwriting Grammy.

Smith turned the baby boy over to her brother and sister-in-law, who believed in God and obedience but had little patience for prodigal sons or sultry singers. Payne grew up in Marietta, Okla., and Vidor, Texas, and by his teens was well-versed in the penalties of wickedness.

“There was a hard edge of discipline in my life, a very strict set of rules that I was to live my life by in that house,” he recalled. “It was very certain that country music and a life of being a ‘rambling whore’ wasn’t going to be my life.”

He strove to meet his aunt and uncle’s expectations but couldn’t reconcile their image of his mother with the striking and charismatic woman who bopped in every so often and snuck him out to a show.

“I remember this woman who was beautiful, big hair, tight pants, smelled like roses and jasmine and cigarettes and Certs,” he said. “She came blazing through my life every nine or 10 months with stories to tell. We’d go on these great adventures. I’d listen to the radio every day, and that lady that they called my mom was singing me songs.”

Payne said his “stand-in parents” and his mother agreed on one thing — he should avoid Jody Payne and his hedonistic lifestyle. Sixteen years passed before Waylon finally met Jody, whom he characterizes as “southern Alabama good people.” Still, it took a while for them to establish a friendly relationship. Back then Waylon was a “hardcore Bible-thumper” intent on saving the world and pleasing the couple who raised him, even as he secretly longed for the adventurous life of his mother.

Fresh out of high school, he enrolled in a seminary. An internal battle seesawed during his first year at Oklahoma Baptist University, when he discovered that the Lord works in mysterious ways.

More to the point, he discovered sex.

Carnal desires can crimp a budding minister’s future — perhaps more so considering that Payne’s first partner was a Catholic monk. Throw in budding affections for beer, marijuana, and popular music, and his downfall was complete in the eyes of his foster parents.

Carnal desires can crimp a budding minister’s future — perhaps more so considering that Payne’s first partner was a Catholic monk. Throw in budding affections for beer, marijuana, and popular music, and his downfall was complete in the eyes of his foster parents.

“I haven’t seen them since,” he said. “I was branded a sinner and basically disowned.”

Payne’s stories of butting heads with people — it seems to happen a lot — typically include plenty of self-blame and end with him extending an olive branch, including one to his aunt and uncle.

“I wish them well,” Payne said. “I wish them peaceful dreams at night. We’re just not compatible folks.”

Forgiving himself took longer. Payne spent 10 years “working to get out from under the guilt I was feeling for being a failure in the eyes of God, because I had previously committed myself to live in His servitude,” he said. “He was forgiving. I don’t think He thought I was cut out for it anyway.”

Payne is now content in his own skin, yet aware that public discussion of an alternative sexuality can hurt someone scrambling for footing on the entertainment biz’ slippery slopes. A music industry insider who asked not to be named put it this way: “Once he becomes famous, he could probably ease out that personal information, and it wouldn’t be bad, because people would know him and love him by then; now is too soon.”

Payne walks his own path. He didn’t want this article to make a big deal about his sexual preference, but he didn’t want to hide it either.

“I like who I like, and that’s that,” he said.

Some fans of Outlaw music might get so tangled up in the particulars of Payne’s situation they will overlook the fact that his attitude defines the genre: “Outlaw” is all about rebellion and freedom.

A succession of menial jobs followed his seminary stint, including two weeks flipping burgers at McDonald’s. He became a carpenter by trade but didn’t limit his horizons; for a while he was chauffeur to prostitutes working for a Nashville escort service.

“I had five girls assigned to me each night, and I would drive them to their appointments and pick them up and make sure they weren’t hurt,” he said, adding that he “wasn’t a pimp.”

During his 20s, Payne began singing at parties and clubs. He had a crystalline voice, and he enjoyed letting it soar. Finding musical accompaniment was difficult, so he taught himself guitar. Then came songwriting. In the late 1990s, he met singer-songwriter Shelby Lynne in Nashville and told her how much he loved her music. This golden boy with the voice of an angel and energy of a dervish impressed her. They became friends, he joined her band as a backup singer, and they co-wrote songs. But Payne’s erratic behavior, fueled by whiskey and speed, soured the working relationship within a few years.

During his 20s, Payne began singing at parties and clubs. He had a crystalline voice, and he enjoyed letting it soar. Finding musical accompaniment was difficult, so he taught himself guitar. Then came songwriting. In the late 1990s, he met singer-songwriter Shelby Lynne in Nashville and told her how much he loved her music. This golden boy with the voice of an angel and energy of a dervish impressed her. They became friends, he joined her band as a backup singer, and they co-wrote songs. But Payne’s erratic behavior, fueled by whiskey and speed, soured the working relationship within a few years.

“I was her best friend, and she got a shot at [success], and I got real freaked out about it because that’s where I wanted to be,” he said. “Shelby fired me because I was a drunk ass.”

He found himself unemployed in Los Angeles, pursuing acting gigs, roaring at parties, and exploring the local country-rock scene.

“I was in Hollywood and either going to end up in the gutter or on a marquee,” he said.

Walking home from a pot dealer’s house one day, he took personal inventory. His musical lineage wasn’t getting him anywhere, his acting chops were unnoticed, he’d been dumped by his best friend and music collaborator, and he was so broke he could only afford a $20 bag of pot each week, which in LA amounts to a few skinny joints. As he walked and thought, lyrics formed in his head: “Just a while ago I thought I had it all … ”. The song would evolve into “Her,” a story about surviving a wrecked relationship.

The phone rings

I don’t jump out of the chair I’m in

’Cause I know who ain’t waiting for me on the other end … it’s her.

Songs began flowing, and most of the album was written in a matter of months. Texas Music stalwart Pat Green was opening for Willie at an outdoor concert in Los Angeles sometime around 2003 and met Payne backstage.

“He had a demo copy of about six or seven songs that ended up making it on The Drifter,” Green remembered. Not only were the songs incredible, but the voice had a range that wouldn’t quit. “I’ve always said Waylon was the most incredible male vocalist I’d ever heard,” he said.

Green was about to start recording the album that became Wave on Wave, and he asked Payne to sing background harmonies. They co-wrote two songs — “Elvis” and “Sing ’til I Stop Crying.” Green had little doubt that Payne would find an audience one day.

“If a guy like Waylon gets heard, people are going to go nuts over him,” he said. “He’s so shocking. The things that fly out of his mouth make you think he’s made to be a star. I’m a believer.”

Nashville rebel Keith Gattis, who’d relocated to Los Angeles, was impressed by Payne’s songs and offered to produce his debut album. Payne borrowed $30,000 to make the record and later carried the master disk with him to New York to visit Willie & Family at a concert. Green was there to open the show. Once he heard Payne’s new album, he called his record company, Universal Republic, and then encouraged Payne to go push for a deal.

Nashville rebel Keith Gattis, who’d relocated to Los Angeles, was impressed by Payne’s songs and offered to produce his debut album. Payne borrowed $30,000 to make the record and later carried the master disk with him to New York to visit Willie & Family at a concert. Green was there to open the show. Once he heard Payne’s new album, he called his record company, Universal Republic, and then encouraged Payne to go push for a deal.

“I took the master [recording] and a cab across town and walked in and met with the president and walked out with a quarter-million-dollar deal 20 minutes later,” Payne said. “It was that good of a record, I knew that.”

While Payne was busy blowing $250,000 in a matter of months, the company sat on the record. And sat. And sat. By the time The Drifter surfaced a year later, Payne was involved in Walk The Line and unavailable to tour. Record sales were dismal, but Drifter captured the attention of other artists, and they began covering the tunes. At the 2005 Mickey Newbury Songwriters Festival in Austin, the festival namesake’s daughter, Laura Shayne Newbury, prefaced a set by talking about music that oozes feeling: “I will tell you this, if you want to feel something, go find one of Waylon’s albums, The Drifter, that came out. I promise you, you will not regret it. Keep searching until you find it.”

When Amazon.com recently asked Nashville singer Lee Ann Womack to share her favorite music, she described Drifter as “achingly great” and put it atop her list of Music You Should Hear: “Not only is Waylon a great writer, but the heartache in his voice is so believable, it just pours out of the stereo speakers,” she said.

While country music artists were covering Payne’s songs, David Arquette (husband of Friends actress Courteney Cox) was among numerous Hollywood producers seeking his acting services. Guest spots on CSI and Wanted were interspersed with movie roles. Payne was disciplined while working, but living the high life away from the set.

Returning to Nashville with Walk the Line on his resumé, he was embraced by the same music industry that had paid little attention to him beforehand. In typical Payne fashion, he thumbed his nose and told entertainment writer Stephanie DuBois, “I’ve never felt more welcomed anywhere in my life than I did at the CMAs when they were all rushing to kiss my hiney and say ‘Oh, we’re proud of you.’”

Looking back, Payne realizes he reveled too much.

“As much as I’d like to stand here and say I was solid as a rock, I was a fucked-up stupid dummy for a little bit,” he said. “Obviously the Hollywood lifestyle of being a rockstar jet-setter is out. I was so whacked, I was seeing ghosts and shit. It was a hardcore experience, and I’m just a dumb country fuck.”

The Nashville establishment might kick him back to the curb once Crazy is released. The movie portrays early music executives as robber barons, thugs, and racists and ends with Payne’s character threatening people with guns, getting committed to an asylum, and receiving electroshock treatments. I watched the movie, and while the screenplay drags at times, there’s little doubt it’s a tour de force for Payne.

The Nashville establishment might kick him back to the curb once Crazy is released. The movie portrays early music executives as robber barons, thugs, and racists and ends with Payne’s character threatening people with guns, getting committed to an asylum, and receiving electroshock treatments. I watched the movie, and while the screenplay drags at times, there’s little doubt it’s a tour de force for Payne.

His next album is shaping up to be another springboard. The untitled work-in-progress is being recorded in Austin and produced by Stephen Bruton, guitarist extraordinaire. Bruton played in Kristofferson’s band for almost 20 years and met Payne backstage at various shows. They were kindred spirits when it came to music and acting, and the older Bruton evolved into a big-brother figure. They hung out and played music in Los Angeles, and Bruton was the logical choice to helm Payne’s next project. The new album, Bruton said, will be as diverse as The Drifter, which jumps from straight-up country to pop to Christian to rockabilly.

“I like the fact that Waylon is all over the map musically,” he said. “That’s a nightmare for the record companies, but I like it. That’s the same criticism they have about a lot of my favorite artists and favorite records. He’s a great singer, a very unconscious singer. I’ve got take after take of songs that he sings, and each time he sings it, it’s completely different and completely great.”

Bruton, who has appeared in movies such as Heaven’s Gate, Miss Congeniality, and The Alamo, is equally impressed with Payne’s “fearless” big-screen skills.

“He’s a young man, and he’s moving pretty fast,” he said. “He’s making this up as he goes along, which is the best way to do it. The only thing is, later in life you wish you were focused more on one thing, but hindsight is 20-20. I just think he’s very talented, a deep soul, an old soul. Anything he wants to aim himself at, he could rule the roost. I believe in the guy.”

Talking to Payne on the phone in Nashville and trying to set up the initial interview for this story provided early glimpses into the difficulties of lassoing a whirlwind. Our first conversation was cut short with Payne promising to call “right back.” Three days later he returned my call and described how he’d lost his cell (turns out the phone was under a cushion that a dog was sleeping on, or something like that). Anyway, he was about to leave Nashville that afternoon and drive to Fort Worth, and we could get together the next morning at 10. My elementary math skills revealed that a 12-hour road trip wouldn’t leave him much time for sleep; he wasn’t concerned.

Sure enough, the next morning he was sitting on the Stamps’ couch answering questions, drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes, and showing off his guitars, including a leather-bound 1952 Fender Telecaster once owned by Waylon Jennings. The guitar was a gift from Ray Scherr, executive producer of Crazy and former owner of Guitar Center. To get an idea of how much the gift is worth, consider that a regular 1952 Tele fetches about $20,000.

Sure enough, the next morning he was sitting on the Stamps’ couch answering questions, drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes, and showing off his guitars, including a leather-bound 1952 Fender Telecaster once owned by Waylon Jennings. The guitar was a gift from Ray Scherr, executive producer of Crazy and former owner of Guitar Center. To get an idea of how much the gift is worth, consider that a regular 1952 Tele fetches about $20,000.

Payne’s primary reason for driving to Fort Worth was to sing with Womack later that evening at the 12-Man Jam at Billy Bob’s Texas. He was pumped.

“We’re going to go to the Stockyards today,” Payne said. “My God, Lee Ann Womack just cut my song. It’s a beautiful world. It’s a great life.”

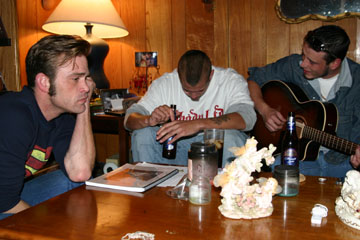

He surprised the Stampses by bringing along a scruffy posse — three nomadic guitar-pickers he had met a few nights before at an open- mic night. These small-town guys from different parts of the country had gone to Nashville to be discovered and naturally jumped at the chance to go on a road trip with Payne and hang out backstage with Womack, Vince Gill, Josh Turner, and others.

Later that afternoon, Payne and his new friends piled into his Mercedes and headed for Billy Bob’s. Backstage security was tight, but a guy watching the door stepped back with uncertainty when Payne, looking like James Dean in cowboy boots, sailed past him with all the confidence and bounce of a superstar. The three ragamuffins and I followed in his wake and settled down on chairs and couches in a backstage area. It soon became clear that Payne had done little in the way of getting clearance to sing in the tightly formatted show. Payne lives on the fly, and technicalities often fall by the wayside.

“His heart is a whole lot bigger than he is,” said Rod Leighton, one of the ragamuffins who hails from Luray, Va., and hopes a music career will save him from a life of pounding nails in shingles for the rest of his life. Leighton wore a toboggan cap pulled low on his head and sported puffy circles under his eyes. He’d jumped in the car with Payne and the others without a penny in his pocket and asked if I could buy him a beer. “I’ll ask Waylon to pay you back,” he said.

At Billy Bob’s, their fairy tale quickly hit a snag. Womack hadn’t yet arrived, and the Josh Turner Band was rehearsing backstage. Waylon’s star-struck posse gushed compliments, which irritated the band members. The room became tense; hard stares were passed, somebody complained, and a Billy Bob’s employee called Payne outside to talk. Moments later, Payne returned and said, “Let’s go. I’d rather be back home picking.”

Bringing ragamuffins backstage to roam among stars is discouraged, and Payne had gotten his hand slapped. He could have told the fellows to wait outside and gone about his business. Instead, he drove back to Mansfield, set up a small eight-track recorder in the Stamps living room, and spent the rest of the night recording a demo of the ragamuffins’ original songs. Turner’s band sings about God’s law. Payne lives it. He’s been helped in his career and feels an obligation to offer a hand to others who are struggling.

Bringing ragamuffins backstage to roam among stars is discouraged, and Payne had gotten his hand slapped. He could have told the fellows to wait outside and gone about his business. Instead, he drove back to Mansfield, set up a small eight-track recorder in the Stamps living room, and spent the rest of the night recording a demo of the ragamuffins’ original songs. Turner’s band sings about God’s law. Payne lives it. He’s been helped in his career and feels an obligation to offer a hand to others who are struggling.

By 2 a.m., I was tired after 16 hours of hanging with Payne and the gang, and I headed home. The next morning he called at 10, telling me to come back and finish the interview because he’d decided to head back to Nashville to drop off his friends, then go to Oklahoma to visit his mother’s grave, and then drive to Hollywood for a meeting.

The next morning, he looked tired but in good spirits. They’d stayed up most of the night recording, and the lines on Payne’s face had grown deeper. Again he suggested we drive while talking.

The day before, we had almost run out of gas with his engine sputtering as we pulled into a station. On this day, his engine oil was running low. He filled the tank, checked the oil, cleaned the windows, and then spent the next few hours sailing over blacktop, talking music and life.

He’s not an easy interview. Both his upbringing and Hollywood taught him to beware the friendly stranger. His conversations are sometimes stream-of-consciousness snapshots jumbled together in haphazard fashion and spoken in riddles that are tough to translate.

After a while, I became frustrated and told him I was having trouble figuring out what made him tick and was worried that my story would be superficial. Finally, the wall began to crumble, and he told me his story, all about his insecurities, family lineage, drug problems, the vampires he’d run across in the music and movie industries, and his traveling-light lifestyle.

At one point we pulled off to the side of a gravel road to take some photos, and an old man came out to accuse us of trespassing. Payne apologized for the inconvenience, flipped his jacket over his shoulder, and headed back to the car, unaware that he’d dropped a pack of rolling papers, which the irritated man was quick to point out. We laughed and roared off down the road again.

Most of his possessions fit in his Mercedes. He has no permanent home.

“I’ve got some guitars, a few pairs of Wranglers that fit well, and some shirts that are easy to care for. It’s a simple life, dude,” he said.

One of his shirts is emblazoned with the Superman logo. The big “S” is also affixed to his back windshield, a belt buckle, and cell phone. It’s partly homage to his mother Sammi, but also represents the man he’s had to become to deal with his past, his relationships, Nashville, and especially Hollywood.

“You have to be made of steel,” he said.

Driving back to Mansfield, Payne tired of talking. He put one of his mother’s c.d.’s in the stereo and cranked it up. Lost in thought, he must have started second-guessing some of the things he’d shared with a reporter. He turned his head, squinted, and asked with suspicion why Fort Worth Weekly wanted to feature him in a cover story. He seemed to be expecting a hack job, another knife in his back, another vampire come to extract a pound of flesh.

Driving back to Mansfield, Payne tired of talking. He put one of his mother’s c.d.’s in the stereo and cranked it up. Lost in thought, he must have started second-guessing some of the things he’d shared with a reporter. He turned his head, squinted, and asked with suspicion why Fort Worth Weekly wanted to feature him in a cover story. He seemed to be expecting a hack job, another knife in his back, another vampire come to extract a pound of flesh.

His question was surprising because the answer seemed so obvious.

“You are going to be a fucking star, and I wanted to write about you while you’re on the cusp,” I said.

He let that sink in for a moment, and then he smiled and stuck out his hand for a shake. We hit the entrance ramp at I-20, and he sang along with his mother the rest of the way home.

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.

[…] Read this fantastic cover story on Waylon Payne from Jeff Prince that was first printed 7 years ago. […]

My new folio

http://arab.girls.tv.yopoint.in/?post.jazmin

rahman vedep teachers rye apartments