When tickets went on sale for a Toadies show at the Ridglea Theater in June, diehard fans scooped them up within 45 minutes. After that, online scalpers asked as much as $150 for a pair.

But they couldn’t find many to resell: Few were willing to part with their chance to witness the first Toadies hometown show since the band broke up in 2001. As far away as New York City, another Toadies show at the Bowery Ballroom sold out all 500 seats in a day. Why are so many people still so impressed? “Well,” said the band’s former bassist, Lisa Umbarger, “Making a platinum record is less likely than winning the lottery.” In their initial 12-year incarnation, Fort Worth’s favorite punk-rockers went from hit-record highs to the depths of personal and professional desperation, both heroes and victims of the changing face of the music world. After the platinum-selling success of their first nationally released album, Rubberneck, in 1994, the band’s career took a nosedive with the seven-year postponement of their sophomore effort, Hell Below/Stars Above. Burned out on making music, founding member Umbarger decided to leave the band, causing co-founder and singer Vaden Todd Lewis to call the whole thing off.

But they couldn’t find many to resell: Few were willing to part with their chance to witness the first Toadies hometown show since the band broke up in 2001. As far away as New York City, another Toadies show at the Bowery Ballroom sold out all 500 seats in a day. Why are so many people still so impressed? “Well,” said the band’s former bassist, Lisa Umbarger, “Making a platinum record is less likely than winning the lottery.” In their initial 12-year incarnation, Fort Worth’s favorite punk-rockers went from hit-record highs to the depths of personal and professional desperation, both heroes and victims of the changing face of the music world. After the platinum-selling success of their first nationally released album, Rubberneck, in 1994, the band’s career took a nosedive with the seven-year postponement of their sophomore effort, Hell Below/Stars Above. Burned out on making music, founding member Umbarger decided to leave the band, causing co-founder and singer Vaden Todd Lewis to call the whole thing off.

Even with the band dispersed, the Toadies’ music lived on. “Possum Kingdom,” the hit single off Rubberneck, continued to be a staple on major rock radio stations nationwide. Fans converted their Toadies discs into mp3s, kept listening, and refused to let the band be forgotten.

Last year, when Lewis began writing songs for a planned solo album, he realized his new compositions sounded distinctly Toadie-like. Calls to former members Mark Reznicek and Clark Vogeler revealed that they, too, still kept a place in their hearts for their former band. The expectant crowd of all ages and walks of life filling the Ridglea witnessed not a band strolling down memory lane, but a viable modern outfit debuting fresh material off their upcoming Aug. 19 release, No Deliverance. The title track off the brand-new album is about being obsessed, Lewis said. “It’s my acceptance of my role as a musician. It’s my job and my life. Who I am and what I do. There is a comfort in that.” He hasn’t always been so fortunate.

In 1989, Lewis and Umbarger were working at a Sound Warehouse on Camp Bowie Boulevard when the Pixies released Surfer Rosa. “It was so cool and different,” remembered Umbarger. “We were so tired with everything else we were hearing.” Despite the fact that Umbarger knew little about making music of any sort, Lewis was inspired: The time was right for them to start a band. He had learned the fundamentals of music growing up in his father’s East Texas church, but this would be his first foray into modern music. With Umbarger, guitarist Charles Mooney, and drummer Guy Vaughan on board, the Toadies were born. The next day, Umbarger bought a bass guitar and amp. The day after that, the Toadies practiced for the first time in Mooney’s bedroom. Lewis, the only member who’d actually played in a band, taught the others the art of songwriting. From the beginning, the Toadies leaned toward mixing their punk-rock heritage with the storytelling art of classic rock.

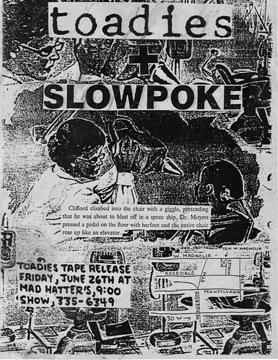

Several months after that inspiration, the Toadies played their first show, at Fort Worth’s original Axis club. They soon made Madhatter’s, the near-downtown club, their home base, and recorded Pleather on Grass Records. But they weren’t exactly an overnight sensation. Melissa Kirkendall, who co-owned Madhatter’s from 1992 to ’94, remembers the band drawing crowds of maybe 50 or so after Pleather came out. By the time drummer Mark Reznicek joined in 1991, Nirvana and the heavy, introspective genre of music had taken over the airwaves. By 1993, the Fort Worth club scene was happening, too, and the Toadies rode the tide. They played with the Goo Goo Dolls, Lemonheads, and Fugazi at the Axis. Lines wrapped around the block. A generation inspired by the darker side of rock reality clamored to experience North Texas’ most popular figureheads for the hard-rock revival that was sweeping the music landscape.

Several months after that inspiration, the Toadies played their first show, at Fort Worth’s original Axis club. They soon made Madhatter’s, the near-downtown club, their home base, and recorded Pleather on Grass Records. But they weren’t exactly an overnight sensation. Melissa Kirkendall, who co-owned Madhatter’s from 1992 to ’94, remembers the band drawing crowds of maybe 50 or so after Pleather came out. By the time drummer Mark Reznicek joined in 1991, Nirvana and the heavy, introspective genre of music had taken over the airwaves. By 1993, the Fort Worth club scene was happening, too, and the Toadies rode the tide. They played with the Goo Goo Dolls, Lemonheads, and Fugazi at the Axis. Lines wrapped around the block. A generation inspired by the darker side of rock reality clamored to experience North Texas’ most popular figureheads for the hard-rock revival that was sweeping the music landscape.

As their audiences grew, the band lost itself in the guttural power of the music they were creating, turning a blind eye to the financial realities of their endeavor. They never dreamed of the success they would still be reaping 20 years later. Umbarger dreamed of being on MTV and quitting her day job as program director for the YMCA. “We went into it blindly, as artists,” said Lewis. The Toadies continued making music for the sheer joy of doing it, not focusing on the potential for profit. As Pleather circulated far beyond North Texas, music fans elsewhere started to take notice. In 1994, the Toadies jumped into Lewis’ non-air-conditioned 1975 Impala and braved the desert on their first visit to the West Coast. When they arrived, representatives from the surging Interscope record label were waiting.

After a show at Los Angeles’ Whisky a Go Go, Interscope offered them a deal on the spot. The band signed with the label that some of their favorite artists, like Helmet and Rocket from the Crypt, called home. Reznicek remembered going home to his two cats as the ink dried on the contract. “I had one hand on each saying, ‘Guys, we made it.’ ” “All of us tried to go back to our day jobs for a while,” said Umbarger. “Mark lasted for a month. The rest of us – two weeks.” By the time the group started making Rubberneck, with Interscope funding, original guitarist Mooney had left the band to become a responsible citizen. Lewis and Mooney´s replacement, Darrel Herbert, filled in. Rubberneck is a snapshot of a band wrapped in the frenzy of bringing their growling post-punk stories to fruition – legendary fruition, as it turned out.

“Radio was God in the early ’90s.” said Reznicek. Even though Lewis was fundamentally opposed to the mass media of commercial radio – “It’s inherently bad,” he used to think – no one could deny that a handful of DJs contributed to the Toadies’ initial success. The album’s famous single, “Possum Kingdom,” electrified the radio waves, leaving the song planted permanently in American pop consciousness. With the song’s hard-earned guitar riffs and Lewis’ calm yet panicky tale about a not-quite-right affair behind a boathouse, the Toadies pulled off a musical coup d’etat: manipulating the pulse of rock ‘n’ roll timing. As Lewis scream/sings, “Be my angel / Do you wanna die? / I promise you / I will treat you well / My sweet angel / So help me Jesus,” the rhythm section of Umbarger and Reznicek skips premeditated beats, distinguishing the Toadies from the most of the era’s popular acts with their ability to get a song stuck in a listener’s head and keep it there.

Buoyed by the success of their music and its strong promotion, the Toadies began a relentless touring regimen that carried Rubberneck coast to coast. First in a van, then a bus, the band played about 200 shows a year for nearly three years, taking off only the odd nights to rehumanize and shower in hotel rooms. “We were best friends at the time,” remembered Umbarger. “We went out with a band called Samiam on a punk-rock club tour. I loved it, and it was great being in a band. We got tight. It was the best thing ever, playing in front of a hostile crowd. Kids quit spitting at us after a while. I wouldn’t change it for the world.” Then in their late 20s and early 30s, the Toadies usually slept in the van and drank and socialized on a nightly basis. “It’s part of the job of being in a band,” said Umbarger, laughing. On quick flights home, Lewis took time to break his lease and put his life possessions into storage.

Buoyed by the success of their music and its strong promotion, the Toadies began a relentless touring regimen that carried Rubberneck coast to coast. First in a van, then a bus, the band played about 200 shows a year for nearly three years, taking off only the odd nights to rehumanize and shower in hotel rooms. “We were best friends at the time,” remembered Umbarger. “We went out with a band called Samiam on a punk-rock club tour. I loved it, and it was great being in a band. We got tight. It was the best thing ever, playing in front of a hostile crowd. Kids quit spitting at us after a while. I wouldn’t change it for the world.” Then in their late 20s and early 30s, the Toadies usually slept in the van and drank and socialized on a nightly basis. “It’s part of the job of being in a band,” said Umbarger, laughing. On quick flights home, Lewis took time to break his lease and put his life possessions into storage.

“We were unencumbered,” said Reznicek. “It was a free existence. We would get in the van and go – see what adventures followed.” As the surreal life on a tour bus, purveying purgatorial music, started to overtake the Toadies’ lives, a fan gave them a tour of an abandoned YMCA building in Milwaukee. After seeing spooky underground basements with swimming pools and clear views of Jeffrey Dahmer’s lot, the Toadies saw how slightly twisted experiences could mimic the music. “The tomfoolery and jokes brought the band together,” said Umbarger. To add fable to their growing fame, the Toadies jokingly painted themselves as surreal icons in a business catering to those who want to leave reality behind, if only for a bit. False rumors circulated about Umbarger’s role as an ewok in a Star Wars movie. An opening band once announced that Reznicek had joined the U.S. Olympic archery team. Crowds to this day still shout, ‘U-S-A, U-S-A’ in his honor,” although the Nebraska native works with sticks, not bows and arrows. Playing in their manager’s hometown, the Toadies claimed that the poor guy liked to decapitate Barbie dolls and do strange and inappropriate things with the severed heads.

Their manager, hired while Rubberneck was in the studio, might not have been a Barbie fetishist, but he was falling out of favor with the Toadies anyway, to the extent that they noticed what he did. Enthralled with their gradual success and bigger and better shows, band members weren’t paying much attention to the business aspect of their ascent. Anything not to their liking was usually blamed on the manager, and when he couldn’t fulfill all their requests, the Toadies fired him. “I used to have an adversarial viewpoint of the world,” said Lewis. With almost a million copies of the album sold, Lewis took the reins and acted as the band’s manager for a while. “The more hands-on you are, the better off you are,” Lewis said. “It adds to the confidence, but it’s still a huge risk. So much can go wrong at every step. It’s a big gamble every day, so hold your breath.”

Umbarger recalled sitting at the front of the tour bus with Reznicek, reveling in gratitude at the opportunities she and her bandmates were enjoying. After years of touring and cannonballing success, the Toadies were ready to get off the road and back into the studio. Fans were ready to hear how the Toadies would follow Rubberneck. But from the highest of highs they were heading for a cliff. A shaky working relationship with Interscope started to undermine all the progress they had achieved. Off tour and back to reality and life in the Metroplex in 1996, the Toadies made their first big shift by firing Herbert. “In our minds, he wasn’t enjoying the lifestyle as much as we were. He got grumpy,” Umbarger said. “It was like we fired the dad.” In retrospect, she said, it was a bad move because the band lost Herbert’s experience in the business from his days at RCA Records. But they forged ahead, auditioning guitarists to take his place, and settling quickly on Clark Vogeler, formerly of the Dallas band Funland.

By this time, the band was working on what would be Feeler, the more experimental follow-up to Rubberneck. Vogeler had assumed he’d spend six months or so helping write the group’s sophomore album, then get back on the road. “It didn’t go as hoped,” he said.

“It [Feeler] was a good record,” said Lewis. “It was pushing the sound. It had different boundaries. Maybe that’s what the label hated.” Interscope repeatedly rejected the material the Toadies sent, forcing them to go back to the drawing board over and over again. While Interscope fiddled, the Toadies’ chances for music stardom were burning. The grunge buzz had died down. Acts like No Doubt, the Foo Fighters (Dave Grohl’s smilier, happier answer to Nirvana), and the hardcore Tupac Shakur ruled record sales. Interscope wanted the Toadies to turn out a single that would smash into the public’s ears and didn’t feel it was getting one. Major labels had taken to cold-calling for market research, playing a random 30 seconds from a band’s unreleased album and making publishing decisions based on the responses.

“We got that phone call six times in two and a half years,” recalled Vogeler. “It was hard to be creative. This is part of what is wrong with the music industry: Major labels get a band they feel is worth something, then they refuse to let the band be what they are.” Umbarger remembered the Feeler sessions as the product of a “mature band working in unison to make the music.” Interscope wasn’t having it, though, and officially nixed the entire effort. In the hiatus from touring, the Toadies were gradually fading from the public eye, leading to a lot of frustration within the band. “Feeler would have been a great second album if Interscope hadn’t screwed the pooch,” said Vogeler. In 1998, en route to production, the album was declared DOA, although unofficial copies still circulate on the internet. “It was hard to deal with rumors about a sophomore slump. It was a real mental time for everyone. We were in our heads,” said Umbarger.

The Toadies took a deep breath and started again. The new effort would be entitled Hell Below/Stars Above. It included some half-finished ideas from the previous songwriting sessions. The band laid down the material at the legendary Sunset Sound studios in Los Angeles, where they spent their free time schooling Green Day bandmembers in pinball games. Undeterred by the negative input from their label, the Toadies captured an unquenchable enthusiasm on Hell Below/Stars Above. The album begins with the quick rocker “Plane Crash,” in which Lewis declares, “We’re itching, we need it / You’re broken, you’re bleeding / We’re living, we’re learning / We’re watching you burning / We know what we really want.”

The Toadies took a deep breath and started again. The new effort would be entitled Hell Below/Stars Above. It included some half-finished ideas from the previous songwriting sessions. The band laid down the material at the legendary Sunset Sound studios in Los Angeles, where they spent their free time schooling Green Day bandmembers in pinball games. Undeterred by the negative input from their label, the Toadies captured an unquenchable enthusiasm on Hell Below/Stars Above. The album begins with the quick rocker “Plane Crash,” in which Lewis declares, “We’re itching, we need it / You’re broken, you’re bleeding / We’re living, we’re learning / We’re watching you burning / We know what we really want.”

Although they were (and still are) collecting some royalties off Rubberneck, times were lean to say the least. Umbarger started working at a Starbucks in the mornings so she could have time for the studio later in the day. The band hadn’t played much in public since 1996, and the millennium had come and gone. Vogeler resented having to “borrow money from my girlfriend for toilet paper and frozen pizzas.” Delighted with the catchy, schizophrenic title track of what “should have been a good third album,” Vogeler said, Interscope finally released Hell Below/Stars Above in 2001. What happened next would shock even the most jaded music aficionado.

“We were like a paper boat in a gutter,” Umbarger explained, “from the street to the sewer.”

The bandmembers are still bitter about the way Interscope handled that album – seven years in the making by the time it hit stores. The sleeping giants who had come so far from their Fort Worth late-night concerts were forced to face a cruel reality of what was transpiring in the music industry.

By 2001, music fans had downloaded untold billions of songs by file-sharing on Napster and similar web sites. The focus was no longer on new releases, since listeners could choose from the whole back catalog of recorded music history, free with the click of a button. The top-selling album of 2001 was a collection of the Beatles’ number-one hits. Labels were in a tailspin, wondering how to deal with profits quickly being flushed down the toilet. The Toadies were the last thing on Interscope’s corporate mind, and the neglect showed. “They did the minimal amount they were legally required to do,” said Reznicek. Hell Below/Stars Above was given a mere two-week shot at capturing listeners on the radio. With all their original contacts gone from Interscope, the band didn’t even have anyone to call and complain to. Like a pink slip delivered by faceless bosses in a corporate wasteland, Interscope informed the Toadies they would not be promoting a second single. It killed their spirits.

The tour under way to support the album was lousy with half-full shows. Worse, the fans who showed up kept asking when the new album was coming out. The band had to sadly answer that it had come out the previous month. The Toadies were “demoralized,” Reznicek said.

Vogeler said the worst part was “that we weren’t even given a shot. I didn’t feel it was worth five years of my life – a considerable fraction of each of our lives.” Tension and dissatisfaction were building on the tour bus, although no one had come right out and said it. “I was banging my head against the wall, and the writing was on the wall,” Umbarger said. “Something needed to change drastically to set things right. We should have been happy on the road. It was the coolest thing ever, but it wasn’t happening. We should have laid the foundation earlier, but we didn’t pay attention.” On the road, the group went from tension to catastrophe. Umbarger told Lewis she wanted to leave the band.

The next day, with the bus rumbling through Tennessee, Lewis called a band meeting to effectively call it all quits, claiming they couldn’t go on without her. The group would play a small Texas farewell tour, and that would be the end. After 12 long years, so much of it spent dangling in a heart-wrenching purgatory, the Toadies were no more. Eerily, Lewis foreshadowed the dissolution on “Doll Skin,” the final track of Hell Below/Stars Above. Over a lamenting, hallucinatory foundation, he proclaims, “Catch that light / It falls in subtle patterns / It crawls in and tells them when their time is up / And now it’s over / Where have you gone?/ You’re still a part of me.” Umbarger didn’t expect the bitter feelings that simmer to this day. (Lewis still won’t talk about the split.) “I still consider everyone my brothers,” she said. “We did everything together. These were the people I talked to a thousand times a day. … I compare being in a band to a marriage, and this was like a divorce.” She now works as a reiki master, channeling healing energy, and plays with a band named Tile. Umbarger still talks to Reznicek and Vogeler, but she and Lewis have yet to reconcile.

The next day, with the bus rumbling through Tennessee, Lewis called a band meeting to effectively call it all quits, claiming they couldn’t go on without her. The group would play a small Texas farewell tour, and that would be the end. After 12 long years, so much of it spent dangling in a heart-wrenching purgatory, the Toadies were no more. Eerily, Lewis foreshadowed the dissolution on “Doll Skin,” the final track of Hell Below/Stars Above. Over a lamenting, hallucinatory foundation, he proclaims, “Catch that light / It falls in subtle patterns / It crawls in and tells them when their time is up / And now it’s over / Where have you gone?/ You’re still a part of me.” Umbarger didn’t expect the bitter feelings that simmer to this day. (Lewis still won’t talk about the split.) “I still consider everyone my brothers,” she said. “We did everything together. These were the people I talked to a thousand times a day. … I compare being in a band to a marriage, and this was like a divorce.” She now works as a reiki master, channeling healing energy, and plays with a band named Tile. Umbarger still talks to Reznicek and Vogeler, but she and Lewis have yet to reconcile.

“I envisioned our being friends, going to family picnics, but it didn’t work that way,” she said. “I wasn’t going to play a big part in his [Lewis’] life anymore. There were hurt feelings, and I understand that.” As soon as the Toadies’ farewell tour in Texas wrapped up, Vogeler moved to California and enrolled in film school. He’s worked in the film industry for the last five years and has received three Emmy nominations, including one this year for his editorial work on Project Runway. Reznicek landed on the drum stool for 1100 Springs, an area bluegrass-country band with which he recently played his final show. Lewis contemplated giving up on music but couldn’t do it. He and former Reverend Horton Heat drummer Taz Bentley started the Burden Brothers, which has gotten lots of accolades. The new band took a small-business approach, signing with Dallas’ Last Beat records and eventually moving to the upstart Kirtland Records. The outfit has recorded two albums, Buried in Your Black Heart and RYFOLAMF.

Tami Thomsen, an old friend of the Toadies since the days when they practiced at Last Beat, joined the Kirtland team and deepened her already-good working relationship with Lewis. When she booked shows for the Burden Brothers, club managers often asked about the possibility of a Toadies reunion show. Not until 2005, when the Dallas Observer called to offer them a headlining spot at their St. Patrick’s Day celebration, did the former bandmembers reconsider and join forces (minus Umbarger) for what was to be a one-time deal. “People were going crazy,” Thomsen recalled about the raucous 10,000 in attendance. “We have a kick-ass fan base,” agreed Lewis. “They wouldn’t let it go away.”

Tami Thomsen, an old friend of the Toadies since the days when they practiced at Last Beat, joined the Kirtland team and deepened her already-good working relationship with Lewis. When she booked shows for the Burden Brothers, club managers often asked about the possibility of a Toadies reunion show. Not until 2005, when the Dallas Observer called to offer them a headlining spot at their St. Patrick’s Day celebration, did the former bandmembers reconsider and join forces (minus Umbarger) for what was to be a one-time deal. “People were going crazy,” Thomsen recalled about the raucous 10,000 in attendance. “We have a kick-ass fan base,” agreed Lewis. “They wouldn’t let it go away.”

The overwhelming enthusiasm led to a repeat performance at the 2006 St. Pat’s festival, then to a small string of shows last December. No one was planning an official Toadies reunion, but the door had opened. Two of Lewis’ original bandmates in the Burden Brothers left that group last year. The remaining members plan to resume eventually with a new lineup, but in the unplanned free time, Lewis began writing material for what was to be a solo effort. Listening to his creations, though, an old familiarity descended, and the rebirth of the Toadies fell into place easily (especially since the group’s old contract with Interscope had, mercifully, expired). When producer David Castell, who has credits for both Burden Brothers albums and with Blue October, got the call about the possibility of working on a new Toadies album, it was a no-brainer. “Sign me up,” Castell answered. “Ever since I heard Rubberneck, it has been a personal goal to record a rock ‘n’ roll classic. So this is ironic.”

With Kirtland’s financial support, Lewis, Castell, Reznicek, and Vogeler joined in Austin in March to record the drums and bass guitar tracks for what would become No Deliverance. Lewis handles Umbarger’s former role as bass guitarist on the album, and the band hired former Hagfish low-end man Doni Blair to take her place on stage. The band finished the guitars and vocals (which Lewis likes to deliver at 10 a.m.) in Lewis’ hometown, at Bart Rose’s Fort Worth Sound studio. Recording the Toadies was a unique experience for Castell, who appreciated how every member took an active role in each part of the recording process. “It was everyone’s opinion,” he said. “They were all on board.” Castell finished the mixing at his Controlled Panic Recording Studios in Dallas. “Kirtland gave us plenty of time and resources,” he said, “and that is rare in this day and age.”

After their bitter split with Interscope, the new, re-energized Toadies are happy to call Kirtland home. John Kirtland, a former member of pop-famous Deep Blue Something, started the label. The Toadies find it easier to trust fellow musicians rather than businessmen as working partners. The Kirtland team, led by manager Thomsen and including two publicists left over from the Interscope days, “are in it for the right reasons – to encourage creativity,” Vogeler said. “The music industry is hard no matter who you are,” Thomsen said. “No certain formula guarantees success.” Kirtland’s ready to do whatever it takes to reverse the Toadies’ misfortune and spread No Deliverance to all the Wal-Marts and iTunes libraries in the land. “My life is 24/7 Toadies,” said Thomsen. “I’m on the phone booking shows,or I’m sitting on the floor sending 500 copies of the single … but I still don’t think my parents believe I have a real job.”

So far, a little effort is going a long way. Building on the seven-day June stint, which included the Fort Worth and New York shows, the Toadies will soon embark on a 28-stop Midwest journey highlighted by a gig at Chicago’s Lollapalooza and the inaugural Dia de Los Toadies at (surprise!) Possum Kingdom Lake on Aug. 31. The band is planning to make it an annual festival modeled on Willie Nelson’s 4th of July Picnic and will include area talent. This year’s supporting bands include Dove Hunter, the Tejas Brothers, BAcksliders, and Lions. Plans are also in the works for a spring 2009 European journey, which will be the first overseas opportunity for the band. These days, Lewis can control more details of the scheduling, allowing him one week a month to return home and spend time with his wife and 5-year-old daughter.

Somehow the Toadies, “are in a better spot than we were in 2001,” said Vogeler. He estimates that when Lewis asks the crowds how many are seeing the Toadies for the first time, about half say they are. Kirkendall is taking the first steps in what will eventually become a Toadies documentary. She has footage of fans, some as young as 16 and 17, waiting in line at shows. When asked how they know the band, many answer that their parents turned them on to the group’s raw rock, still relevant and good 15 years later. The inclusion of “Possum Kingdom” on the second version of the popular Guitar Hero game hasn’t hurt things, either. One thing in particular draws several generations of listeners into the Toadies fold: quality music. In No Deliverance, the music is more in touch with blues roots, leaving wide-open spaces for Vogeler’s personality-laden, forceful guitar work. Reznicek still cleverly masks the tricky rhythmic undulations and draws on his recent experience playing country music. In the barn-burning “Hell in High Water,” his rapid-fire train beat pulses and deviates from the traditional post-punk groove.

No Deliverance’s distinctly Texas sound derives, at least in some small way, from the predilection the Toadies had for listening to ZZ Top during the recording process. Reznicek noted the irony: He converted his ZZ Top vinyl to a digital file format, then broadcast it through an iPod. Welcome to 2008. Both futuristic and a throwback, No Deliverance captures the band’s commanding energy while putting the ostensible anger on a slower burn. “We wanted to keep it as ‘fuck you’ as possible,” Lewis said. The singer wrote most of the material from his home. With input from other members, each song reveals a band mastering and manipulating complex layers of music. Whether it’s a precautionary tale like “One More” or the proud stoicism in “I Am a Man of Stone,” Lewis’ adult-punk tales of life keep tweaking the imagination.

“I can’t be disappointed,” said Vogeler. “I can’t lose if I’m having fun, and this couldn’t go any better. … Music is best if it’s a little bit dangerous, if it gets your mind going and your blood flowing.” No Deliverance, as sophisticated as it may sound, accomplishes both.

It almost seems as though Lewis designed the Toadies’ career like he designs their music – owing many of its stripes to the clever way it relates to time, but also, it sometimes seems, standing outside of time. “It’s not contrived music,” he said. “I like playing off what feels right … and I like to set someone up for something they learn to expect.” Toadies fans have been hoping, if not expecting, a third album for seven years. It’s a heck of a setup.

Freelance writer Caroline Collier can be reached at caroline.collier@att.net.