Somehow, the upper reaches of stardom have always seemed to just elude Jeff Bridges’ grasp despite all his advantages as a well-known actor’s son who came of age during a golden period for Hollywood filmmaking and kept company with great directors who appreciated him. Now he’s 60 years old and hasn’t headlined a big mainstream movie since the regrettable K-PAX (2001).

However, he’s reinvented himself as a powerful character actor and spent this past decade delivering assured, invigorating performances in a number of roles, including a hotheaded, bullying U.S. president in The Contender (2000), a grieving bohemian father in The Door in the Floor (2004), a slick corporate bad guy in Iron Man (2008), and a conscientious media mogul in How to Lose Friends and Alienate People (2008). Even as a burned-out gymnastics coach in the throwaway teen flick Stick It (2006), he still took the trouble to create a lived-in character.

However, he’s reinvented himself as a powerful character actor and spent this past decade delivering assured, invigorating performances in a number of roles, including a hotheaded, bullying U.S. president in The Contender (2000), a grieving bohemian father in The Door in the Floor (2004), a slick corporate bad guy in Iron Man (2008), and a conscientious media mogul in How to Lose Friends and Alienate People (2008). Even as a burned-out gymnastics coach in the throwaway teen flick Stick It (2006), he still took the trouble to create a lived-in character.

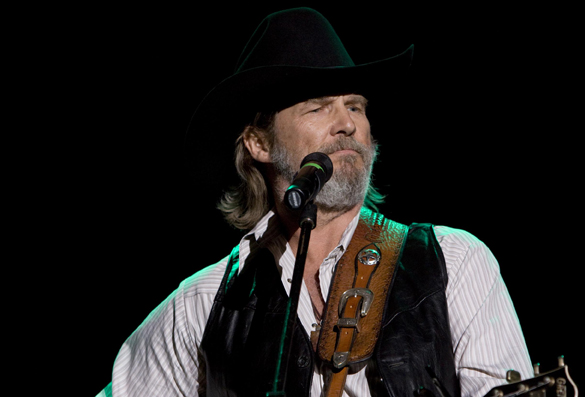

The indie music drama Crazy Heart places him front and center once again, and his performance seems a lock for an Oscar nomination this year, if not the trophy. Bridges portrays Bad Blake, a country singer-songwriter who’s revered as a legend by his fellow musicians but whose hard-living ways have reduced him to a cash-strapped wreck playing with pickup bands in dive bars in remote corners of the Southwest. Bad – who refuses to divulge his real first name – needs to do two things to turn his life around. He has to win the trust of Jean (Maggie Gyllenhaal), the freelance music writer and single mother who falls for him but knows that she tends to be attracted to the wrong guys. And he has to swallow his pride and accept a hand up from his former protégé-turned-country music superstar Tommy Sweet (Colin Farrell, dead on as a slick country poseur) by agreeing to open for him during a stop on his national tour.

Other actors would use the role to beg the audience for sympathy, especially given an early scene showing Bad having to fish his sunglasses out of his own vomit. Bridges instead wears Bad’s drunken dissipation like an old, tattered, comfy shirt, whether he’s wryly laughing it off with a joke in an interview with Jean or being pissed about the latest venue he’s playing. (His first line in the movie: “Aw, shit, it’s a bowling alley!”) Bridges is no less credible as a great musician as we see him perform various songs in public or strum the guitar at home. His musical performances help form the character, too – despite all the abuse Bad has subjected himself to, his talent is still there.

Fort Worth’s T-Bone Burnett is in charge of the music here, and his name on a movie pretty much guarantees that the music will be good (O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Walk the Line). The songs performed by Bad and Tommy are originals mostly co-written by Burnett, some of them with another Fort Worth native, the late Stephen Bruton, and others with Ryan Bingham (who also portrays a backing musician working with Bad). Besides being good pieces of music, they all make sideways comments on the story, from the rowdy honkytonk number “Somebody Else” to the hushed minor-key love song “Hold on You” to Tommy’s brash trucker lament “Gone, Gone, Gone.” Bridges and Farrell team up for a soaring harmonized duet version of the I-wasted-my-life song “Fallin’ and Flyin’.” The climax of the film is provided by “The Weary Kind,” an unassuming, gorgeous desert rose of a song that fully lives up to its billing as the piece that marks Bad’s redemption. As terrific as that is, I must say I personally prefer the sparse, haunting Greg Brown-penned “Brand New Angel,” which Bad performs after he’s just completed a stint in rehab.

The film is based on a novel by Thomas Cobb, and the plot is way similar to last year’s The Wrestler. That’s not a comparison that flatters this movie, which largely wastes both Gyllenhaal and, as one of Bad’s old pals, Robert Duvall. On the plus side, first-time filmmaker Scott Cooper has a decent eye for both the low-rent venues that Bad plays and the stadiums that Tommy sells out, and he does well with Bad’s comical encounters with his few fans. Still, too much of this story plays out in unsurprising ways, and the scene in which Bad loses track of Jean’s young son belongs in a much weaker and more conventional film. If you take Bridges and the music out of this movie, there’s not much left.

Ah, but the easy – and correct – response to that is that they are here. Either Bridges or the music would be reason enough by themselves to see the movie. Together, the two keep the proceedings from degenerating into self-help platitudes or wallowing indulgently in misery, and they make Crazy Heart into something bright and memorable.

hi!,I like your writing so a lot! share we keep in touch extra approximately your

article on AOL? I require an expert on this area to resolve my problem.

May be that is you! Taking a look forward to see

you.