In 1998, Shea Seger was 18 and living in Virginia when she was approached by a British music producer who invited her to England to hang out for a few weeks and maybe, just maybe, write some pop music –– though the native Fort Worthian was a trained singer and had performed in musical theater for years, she had never written music before and had only fiddled with the guitar.

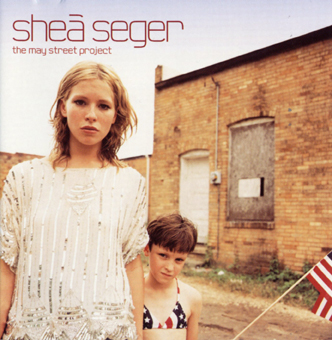

Several months later, Seger signed to major-label RCA Records and, with the help of some co-songwriters and killer session players, released her debut album, the R&B-infused May Street Project. Reviews of May Street and photos of the all-American gal with the thick blonde hair, chiseled face, and radiant blue eyes began appearing in major publications such as The Times, Dazed and Confused, The Daily Mail, The Guardian, and NME. And Sir Elton John told The Face, “I bought 200 Shea Seger albums. I thought it was brilliant. I gave one to Madonna, but she already had it in her handbag.”

A couple of months later, and Shea Seger had vanished from the pop landscape almost as quickly as she had appeared.

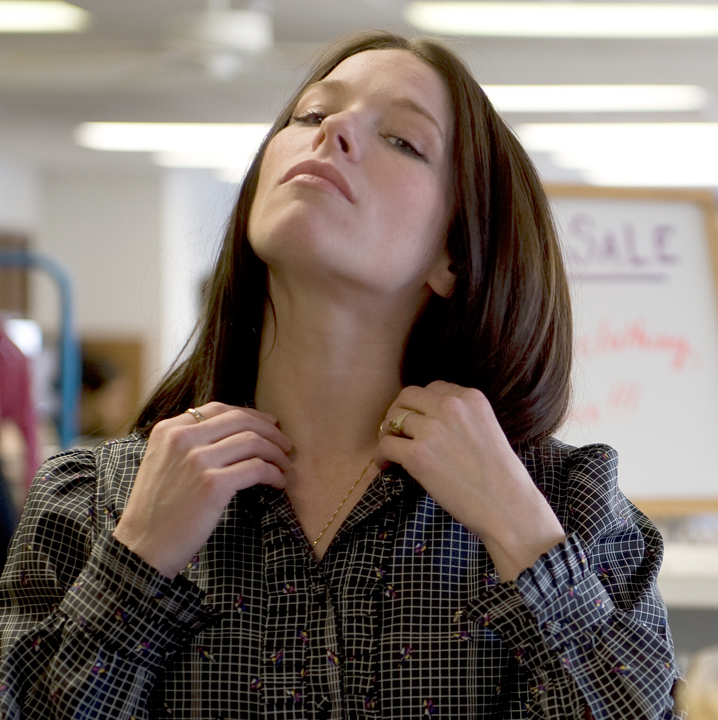

But Seger never stopped writing music. In a couple of weeks, the married, still stunning, mother of 5-year-old Luna Rose will release an eponymous album recently recorded and produced in Austin. Unlike May Street, the new CD is semi-bluesy, semi-folky, and raw: Seger, who has become proficient on guitar, performed each track in its entirety until the take was just right. No editing. No splicing together of different moments of different performances. Just straight to tape. Contributors include bassist Pino Palladino, with whom Seger had worked previously and who now plays for The Who, and Andrew Wallace, Seger’s boyfriend, who has played Hammond organ in the touring band of Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters. Drummer J.J. Johnson, who has played with popular stateside singer-songwriters John Mayer and Doyle Bramhall, among others, also performs on a track.

Seger plans on launching her new album in the place where she got her start: England. “I’m going back to complete my 10-year story, my 10-year story of coming back to the business and playing live,” she said, “even though it’s proven to be a bit of a struggle.”

Seger’s life has always been itinerant. With Wallace and Luna, Seger now hops back and forth between Quitman, where her parents and two younger sisters live, and Fort Worth, where most of her extended family resides. Seger’s grandfather originally moved to Fort Worth from California to work for Convair, the defense-industry company now known as Lockheed Martin. Seger and her parents, Jon and Melinda Smith, relocated to Quitman from Fort Worth when she was a child to take care of some land purchased by Seger’s grandparents, who initially wanted to retire in Quitman but ultimately changed their minds.

Quitman was and remains a little country town. Seger recalls that there was only one television station, a couple of radio stations, and really nothing to do other than maybe go to the park, play games, or ride horses.

Seger’s father, a Vietnam veteran, deejayed at a local radio station, among other jobs, and her mother is an artist and craftsperson. Both encouraged a comprehensive worldview. “I had made up my mind as a kid that I would be out of town,” she said. “My parents didn’t raise me to be sheltered about where I could go.”

Both were also passionate about music. In Fort Worth, they ran a nightclub, Uncle Fred’s Rocker, now known as Froggy’s Boat House, and Seger’s father regularly haunted the honkytonks of local repute. The houses of Seger’s youth pulsed with Texas blues, ’50s R&B, pop (The Eagles, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd), C&W (Hank Williams, Kinky Friedman), and even disco. Seger also took piano lessons as a child.

When Seger was a tween, her parents and their newborn daughter Jordan relocated again, this time to Virginia for Seger’s father to attend graduate journalism school. Though he had never worked as a journalist before, he “always had a gift for writing and English,” Seger said.

Seger attended public high school and also the exclusive Governor’s School for the Arts. She was so committed to the performing arts school that when her family eventually moved back to Quitman, she stayed in Virginia, living with a family whom she had befriended and earning money by working in theater. While performing as the proverbial bombshell in a musical about ’40s-style radio, she met the British producer. Felix Tod had discovered pop superstar Heather Nova and had played in Candyland, an early-’90s synth band that had received some airplay and MTV play but might be best known for being made fun of in a Beavis and Butthead episode.

“I wasn’t happy with my personal life, my relationships, and, politically, I was trying to know what I wanted,” Seger said, leaving out some painful details. “I was really miserable in several areas of my life, especially work-wise. As soon as my [theater] contract was up, I booked a flight, and I was on a plane the next day after I closed a show to go and write music.” In truth, she said, “I was really just leaving. I had to leave. … I had a way out of [the United States].”

Seger spent a couple of weeks writing in a studio in Notting Hill but knew within a couple of days that she was spinning her wheels. But she also knew that she wanted to stay in England. “I loved the English sense of humor, the language, just loved the nuances, even loved the crap weather,” she said. “I really did. … I thought, maybe I’ll pursue someone else to write with. It was interesting. … I didn’t think I’d be able to do [music]. It wasn’t my dream to go out and make a record, to be a musician, but maybe I’ll do it.”

Seger, who was living with various friends and friends of friends, soon met the duo of producer Martin Terefe and songwriter Nick Whitecross, whose collective pedigree was impressive. Terefe would go on to win a couple of Grammys for his work with pop idols Jason Mraz and Colbie Caillat, and Whitecross had been in the popular British band Kissing the Pink. “I thought, ‘OK, I don’t know what I’m doing, but I can ride on this,’ ” Seger said.

From writing sessions that began “laying back stoned on futon beds,” the three collaborators developed several songs. The recording process, however, was not as organic as she had expected. “I was [operating] on remote,” she said. “It was the opposite of everything I had been raised on: people playing and things happening in a room and it being recorded. It was not that. I was told exactly how to sing. … I was not allowed to listen to what I had just sung.”

Songwriting was a learning experience but a good one. Seger thanks Whitecross specifically for teaching her the rudiments of pop-song architecture. But the pressure to perform in certain extremely stilted ways deadened her creative spirit a little. Still, she is proud of the record, even though she was “very distant from it musically.”

Songwriting was a learning experience but a good one. Seger thanks Whitecross specifically for teaching her the rudiments of pop-song architecture. But the pressure to perform in certain extremely stilted ways deadened her creative spirit a little. Still, she is proud of the record, even though she was “very distant from it musically.”

The three collaborators, she said, “started courting major labels on both sides of the water.” Seger, who did not have a manager and was handling business mostly by herself, decided on RCA U.K., whose people had won her over.

As the creative trio was finishing up what would become The May Street Project, Seger took on a manager and a press agent and began doing the press circuit. The profiles that appeared often disappointed her, mainly because most of them were either clichéd or semi-fictional. The story that British journalists insisted on telling –– despite pesky facts –– was primarily one of Cinderella proportions. British journalists “love that rags-to-riches [theme],” Seger said. “I think that really took hold very early on with the first couple of pieces.”

In one particular piece of fiction the claim is made that Seger started writing music when she was two years old. In another, she made her way through a crowded bar, stood atop a table, and began singing an a cappella version of “Bobby McGee.” “A lot of [the press] was just so slanted,” Seger said. “I learned a lot. I wouldn’t trade it, though much of it was angering and embarrassing at the time.”

RCA honchos did not dislike the idea of having a countrified sex symbol on their roster. “The label really wanted me to dress like ‘Britney’s country cousin,’ ” Seger said, referring to an article in The Daily Mail. “I was flooded with stylists –– with no taste. … I was, like, ‘C’mon, are you serious?’ ”

Seger did not buy into the corporate rock-star lifestyle –– the fashion photo shoots, the critical adoration, the fame –– and she continued traveling back and forth between England and Quitman to visit and also to help her parents take care of Jordan and another new daughter, Morgan.

The singer-songwriter finished the album to uniformly positive reviews. Seger, The Guardian said, “has one of the most intoxicatingly come-to-bed voices since Ricki Lee Jones.” The Guardian also described a live performance of one May Street track as “an angry, wistful, moving trawl through her Texas upbringing … told with the same elegiac air Van Morrison applies to his stream-of-consciousness Belfast childhood stories.” The Times said that May Street was “mood music for grown-ups, not manufactured folk-pop.” Q Music said the album “swaggers with a fluent Deep South ease, even showing a surprisingly sweet tooth for trippy beats.”

With a stout backing band, Seger did two tours of England as an opening act: one with a band called Toploader and another with the seminal British New Wave band James.

British MTV had been airing videos of two of Seger’s songs, “Clutch” and “Last Time,” when RCA decided to introduce her to the United States via a lot of press and “Clutch.” Though college radio embraced the song, commercial radio proved to be a little less enthusiastic. The May Street reviews were less plentiful than in England but also positive. May Street, TIME magazine said, “is a surprisingly smooth listen for an album that boasts such seemingly disparate influences.”

U.S. publications, however, merely promulgated some of the same myths established across the pond. Seger recalls a particularly flabbergasted reaction from the woman she calls her “Virginia mother” to a particularly fiction-riddled article that appeared in Elle magazine. “My [Virginia] mother called me and was, like, ‘Shea, first of all, why didn’t you tell me that you had a piece in Elle?’ ‘Ma, I don’t know.’ ‘Well, please tell me that you didn’t say this,’ ” and Seger’s mother would go on to quote something that had been inserted unceremoniously into Seger’s mouth. With her band, Seger did two tours of the United States as an opening act: one with British singer-songwriter David Gray (of “Babylon” fame) and another for a budding American pop-blues singer-songwriter named John Mayer. But airplay and MTV play were still elusive.

After May Street, Seger began writing on her own “absent of [Whitecross], absent of formula.” And she decided to do it in East Texas.

Seger enlisted the help of two “kindred musical spirits” with whom she had performed previously in live settings in the States: guitarist Chester Kamen (Paul McCartney, Madonna, Bryan Ferry) and bassist Dale Davis (who would go on to perform with multi-platinum British recording artist Amy Winehouse). At the end of the Mayer tour, the group holed up in a house in East Texas with no telephone, no television, no clocks, and no computer — just a keyboard, drum machine, microphone, one drumstick, and a couple of guitars. Seger said she was completely focused on writing, which is when she realized that the corporate-influenced May Street recording process had not utterly stripped her of her natural songwriting instincts. “That was when I started to realize I can kinda do this,” she said. “I don’t know what I’m doing, and it’s not what [Whitecross] taught me, but it’s still good, like, ‘Huh?! Maybe I am a music writer. Cool.’ ”

Seger had assumed that what she and her bandmates were working on would be her next album on RCA. But when she returned to England, the corporate mergers that would effectively neuter originality in mainstream music had begun. “I saw heads being chopped 24 hours straight,” Seger said. “People who had been there for years, who had championed you, were replaced by whoever. Within four days you walked into a totally different regime.”

The U.K.’s Pop Idol, the forerunner to the States’ American Idol, had exploded, which meant that labels no longer had to nurture new artists but merely to capitalize on the semi-stars created by the completely populist process of voting.

RCA’s “new regime,” Seger said, was made up of bean counters. “They weren’t music guys,” she said. “They were old stuffed shirts. They wanted ‘Britney’s country cousin,’ ” she said. “I said I can’t do that, and I asked them to drop me at that point. And they agreed.”

Seger owns the East Texas material and hopes to release it one day — maybe sooner rather than later. “We had a lot of great, honking hit songs,” she said.

Seger owns the East Texas material and hopes to release it one day — maybe sooner rather than later. “We had a lot of great, honking hit songs,” she said.

Around the time of her breakup with RCA, she met Wallace in England. Within six months, she was pregnant with Luna.

The last May Street-related thing that Seger did was in October 2002, when she performed on Lifetime Television along with the Dixie Chicks, Emmylou Harris, Pat Benatar, and Sheryl Crow, among other mega-watt female singer-songwriters, as part of Women Rock! Girls & Guitars, a now-defunct annual breast-cancer awareness concert.

Working alone, Seger approached songwriting not as a commercial endeavor but a personal one. Times soon got difficult, pushing her songwriting even further inward –– Pink Floyd’s Waters had decided not to tour, leaving Wallace without a steady, well-paying gig, and a neck operation on Seger’s father was tragically botched, forcing the sixtysomething to relearn basic motor skills.

Seger and Wallace took Luna and went back to Quitman to help care for her father. And she kept writing. The confessional, stream-of-consciousness lyrics and music that resulted, as delicate-looking but strong as a spider’s web, was unlike anything that Seger had believed she could or would do. She compares her writing at the time to throwing up. “I’m not a person that’s afraid of puking,” she said. “If that’s what I need to do to feel better, then give me whatever [to write with]. It could be with a crayon on a napkin. It could be eyeliner on a business card.”

She had never seen herself as a person who escaped into her songwriting. “But I’ve learned now through the completion of all this that clearly I did go there,” she said.

She kept her music to herself, though. “I never wanted to write [confessional music], which is why I always wanted to be a playwright and an actress,” she said. “The real stuff going on my life was a bit too intense and heavy … and that’s the last thing you want to write about if you’re trying to get into music, especially if you’re a girl and now a mom. But I had to. It was all pouring out of me, pouring out of me and then being locked in a safe.”

Seger played guitar well enough to write but was “scared witless to play in front of anyone.”

As soon as Seger’s father was able to get by, she, Wallace, and Luna moved to Austin, the Southwest’s largest music community and potentially an ideal setting for Wallace to land session work and gigs. However, little work came his way.

Seger eventually put her performance anxiety aside and, with Wallace’s help and guidance, recorded a demo at home. She sent the CD to an old Los Angeles-based business acquaintance, who listened to the disc and then promptly invited her to audition for him. Seger flew to L.A. on her own dime. When she got there, she performed a couple of songs for him and his wife in their living room. The acquaintance was apparently so blown away that he offered to fund an entire album. The deal, however, was great for him but not for Seger. “I told him thank-you but no thank-you,” Seger said. “I waited this long. I can wait some more.”

Things were getting pretty grim financially when a fortuitous letter arrived indicating that she was owed several thousand dollars in royalties from some overseas sales from May Street. “It was beyond a godsend at that time,” she said.

Seger, who describes herself as spiritual but not religious, went into her backyard and had “a reckoning” with The Man Upstairs. “ ‘If you give me that check,’ ” she recalled telling him, “ ‘I’ll pay my bills, and if there’s anything left over, I’ll book a studio and I’ll pick up that guitar and I’ll just sing some songs.’ Because at that point, it was the only thing I could think to do. It wasn’t a strategy. It was desperation. I was cornered and creatively just stripped, and the only thing that I hadn’t done, the only part that wasn’t exhausted, were the songs in the safe and me with my guitar without anybody else.”

Armed with only her guitar and voice, Seger entered Wired Recording studios in Austin. Her only stipulation was that she record on analog tape, no doubt a negative reaction to the supremely digitized recording process of May Street. “I went in to face pretty much every fear, every one of my personal demons in that live room,” she said, noting that she had never really played solo in front of strangers.

Over the course of several days, she played her songs repeatedly until she got the takes just right. “It was very hardcore,” she said. “It was not fun. My fingers would bleed. … A lot of times I’d have to stop and, y’know, be a little bit of a mess for a bit and then get back on the chair and go. Do it. Record. Go.”

The output startled her –– and everyone else in the studio. “[Wallace] was, like, ‘That’s wicked!’ … I’ve had amazing encouragement from an amazing caliber of musicians over the years, but I never bought it. I never believed that I kind of owned it, so to speak. … [Recording the new album] was a process of going, ‘OK, this is what I do.’ ”

Only after Seger had performed the songs dozens of times in the studio could she objectively, thoughtfully consider what she had created. “Wow,” she recalled saying to herself, “ you really have grown.”

Wallace contributed to the performances, playing an array of instruments. Additional sounds –– Johnson’s drumwork, Palladino’s bass guitarwork, some strings, accordion playing by Bukka Allen –– were inserted later. Two similar-sounding songs not on the album but recorded earlier in Los Angeles appeared on the soundtrack to Railed, an independent film by an acquaintance.

Recording Shea Segerwas therapeutic for her. “I don’t ever want to make one like it again, but I know that it would have altered me as a performer in every aspect had I not done it,” she said. “For my sanity’s sake, I couldn’t have waited until success deemed it OK for me to make a nontraditional record. It would have killed me before then.”

The songs on Shea Seger are a hodgepodge of straight-ahead bluesy rockers and contemplative, confessional, solo-acoustic ballads. Strength and tenderness are qualities endemic to female singer-songwriters, but what sets Seger apart is her sometimes-gravelly sometimes-conversational voice. She can sound as menacing as a fire-and-brimstone preacher or as vulnerable as a best friend at the end of her rope, whichever the lyrics call for. Any imperfections are voided by her conviction and her commitment to the songs. “I don’t wanna be the one who stares at the sun then begs you to tell me I’m blind,” she sings on the slow-burning “Dew Drops,” really attacking “stares” with a full throat but barely able to bring herself to deliver the strophe’s last few words. To hear Seger perform “Dew Drops” or any other of the record’s moody ballads is to bear witness to either a heart crumbling or battle line being drawn.

The May Street Project was a colorful collection of heavily R&B-inflected, stone-cold pop songs, even the ballads. Critics who heard (and saw) only “Britney’s country cousin,” “the hippie Britney” (NME), or “Dido’s spunky kid sister meets Shelby Lynne” (Entertainment Weekly) totally missed the old-school soul that gives the album its dynamism. In “Clutch,” as sexy an uptempo song as probably ever recorded, Seger sings up, down, and all around the propulsive, danceable beat. “Oh, no,” she sings, the slightest suggestion of a crack underlining the fire burning down below, “You got me goin’ crayyy-zay for you bay-bayyy.” The song also has what could be considered a second chorus. “Let me in your world,” she sings. “Let me in your world for a while,” the desperation as palpable as a furtive touch.

On the new album, the heat of anticipation gives way to a gray, often metaphysical contemplativeness. Though Shea Seger is not long, it is sweeping and epic, with huge chunks of stream-of-consciousness lyrics intercut only occasionally by subtle yet memorable choruses and with no-nonsense fretwork and rhythms. The songs address both spiritual and more earthbound concerns. There are meditations on destiny versus fate, heated missives to charlatans and other heartbreakers, elegies for the living, assertions of purpose, and paeans to the redemptive qualities of love of both the romantic and spiritual varieties. Seger’s lyrical approach is so straightforward and honest it achieves a kind of homespun poetry: light on the storytelling, light on visual imagery, heavy on rhetorical energy. “I’m the piper and I bleed red,” Seger belts out on the stomping, jangly, country-rocking “Piper’s Dream.” “My imagination stole my bread / And now I’m left with a hole instead of a heart / I’m the piper, and I need you / I will bleed you dry enough to prove.” On the jaunty, clap-happy, slide-guitar-spackled “Last Few Standing,” Seger takes the high road. “So we’re suddenly strangers,” she sings over just a crackling beat, her voice airy but masculine. “Someone has to tell you my name / And I saw you last night / It was clear that you had changed / You sold out your mercy / But you won the chance to begin / And now you’d be lucky in a fight to get your ass kicked by a couple of friends.”

Shea Seger could have gone in either of two ways: toward mere college-radio listenability or toward what the album is, a triumph of grit, poetry, and grace. Shea Seger is neither precious nor brutal. It is singular, genuine, as plainspoken and often as intimate as a prayer.

Shea Seger could have gone in either of two ways: toward mere college-radio listenability or toward what the album is, a triumph of grit, poetry, and grace. Shea Seger is neither precious nor brutal. It is singular, genuine, as plainspoken and often as intimate as a prayer.

The cornerstone of the album, in her opinion, is the song “Shells of Men.” Over a gently plucked, barely audible acoustic rhythm, Seger comes on like a world-weary but unbroken believer. “What remains is wearing thin,” she sings, her voice smoky and sweet, “as our wonder years descend / Just take hope / Only shells of men begin again / Only shells of men begin again.” Don’t fret, she’s basically saying. Redemption is at hand, her generous declaration underlined by majestically swelling strings.

Seger had been hollow herself. “People that you find that have the most to offer in life in all different sorts of areas have been broken in some area of their life,” she said. “If you can be broken and be filled [back] in, that is the cornerstone to character that I’ve seen. … ‘Shells of Men’ is why I had to make this record.”

The song –– perhaps the entire album –– could be seen as a reflection of Seger’s life at the time. Her lack of income, her father’s botched surgery, her defection from a major label, her return to the simplicity of Quitman –– she says it all broke her down. Writing was “such a stripping process on all accounts that I was still in a place of dealing with it myself, much less trying to put it on anyone else,” she said.

Commercially releasing her handiwork was only in the back of her mind. “I didn’t think, ‘Oh, this is art –– somebody’s gonna appreciate it,’ ” she said. “It’s not. It’s just life.”

Seger does not know how she will release the album other than online via www.sheaseger.com. Her indecision isn’t born of apathy –– income, she said, is “high on the priority list.” Rather, she believes that setting up a marketing strategy around the album could be karmically dangerous. “I think it’s like tempting fate,” she said. “You can manipulate some things and then do what you know to do and let the rest take care of itself: what things matter, what things don’t, what things are just going to be exhausting. I don’t care in that department, when it comes to strategizing a commercial release of this record. I think it’s gonna do something that it’s gonna do, and I don’t really wanna mess with it that much.”

“I’ve got plenty of albums [in me],” she said, plenty of other opportunities to be “particular … and innovative” about marketing.

With Shea Seger, she said, she wants to make money and gain recognition the old-fashioned way: by performing live. “I won’t have to explain anything,” she said. “I know that when I get on that stage, whether it’s in Texas or in London now, I am who I am, and that’s the thing that will be different and that’s the thing that will set the stakes for everything coming up, whether that be any sort of deal, any sort of investor, any sort of anything.

“What sets me apart is being on that stage,” she continued, “and it doesn’t matter if I’m up and I wanna do a set of Chuck Berry covers. It’s what I do, and that’s the thing I never did get to do before.”

Seger hasn’t lined up a backing band yet but isn’t worried. “If I’m blessed to have astute players join and hold me up like that, then that’ll be great,” she said. “If I don’t, then I’ll get there. It’ll only be a matter of time.”

A big reason for the upcoming move to England has to do with the differences between the U.K.’s musical climate and the United States’. Over there, she said, hard-to-categorize artists are still embraced by mainstream media. Here, she believes, such artists are relegated to the ghettos of college radio and underground publications. Plus, American pop culture often takes its cue from England, dating back to the ’60s.

There are other, pragmatic reasons for the move. Seger’s agent, Rob Light from Creative Artists Agency (George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Oprah Winfrey), told her that she could cover a lot of fertile ground in England without sacrificing much time from her family or spending enormous amounts of money –– the country is only about half the size of Texas. Light also has many industry contacts throughout the U.K.

Seger also wants to return to England to satisfy cosmic harmony. The place where she effectively ended her career should be where she resurrects it.

However, she doesn’t see herself spending the rest of her life overseas. Texas is still on the horizon. “I’m going over there to do a few shows and complete my story and kind of get that under my belt,” she said. “And then come back home.”

[…] 10-year-old daughter Luna Rose have been living for the past few years –– and also where Seger got her major-label start in 2000. Why? Relative newcomer Van Darien is, basically, Shea Seger Lite, and I mean that in a good way. […]