“The movie business is uglier than most things. It is normally perceived as some kind of cruel and shallow money trench through the heart of the journalism industry, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs, for no good reason. There’s also a negative side.” — Hunter S. Thompson

Leave it up to Thompson to get right to the heart of things. The late journalist and author is one of my heroes, along with Muhammad Ali and the late Robert F. Kennedy. The quote has been applied to the TV industry and the music business as well as films. In this article, I get to use it to write about my favorite subject — me.

When I was growing up in Cleburne, I loved going to movies at the Esquire Theater. As a teenager, when I wasn’t making out or getting thrown out, the movies helped me escape the limitations of what was then a rural town of 13,000 residents. When we went back to Fort Worth (where I was born) to visit my grandmothers, I did the same thing at the 7th Street Theatre, down the block from the Carnation Ice Cream Parlor, where I first tasted coffee ice cream.

When I was growing up in Cleburne, I loved going to movies at the Esquire Theater. As a teenager, when I wasn’t making out or getting thrown out, the movies helped me escape the limitations of what was then a rural town of 13,000 residents. When we went back to Fort Worth (where I was born) to visit my grandmothers, I did the same thing at the 7th Street Theatre, down the block from the Carnation Ice Cream Parlor, where I first tasted coffee ice cream.

In none of those places, now all defunct, did it ever cross my naïve schoolboy’s mind that I might someday be part of a major film myself. And I certainly didn’t know that the magical world of Hollywood could also harbor dens of backstabbing, contract-manipulating jerks — many of whom are not the geniuses they think they are. Without the jerks, maybe it wouldn’t have been possible to turn my nonfiction book I Love You Phillip Morris into a film full of cutting-edge material and brilliant performances by superstar actors such as Jim Carrey and Ewan McGregor. On the other hand, without the jerks it might not have turned into a box-office train wreck either.

In retrospect, maybe all of the angst I went through in that process is part of the big cosmic joke. After all, the film is based on the story of one of God’s purest con men, an artiste in the field of walking off with other people’s money, a master of illusion so skilled at escape that sometimes it seemed as if he must have made cell doors simply disappear.

I originally thought I had cut a bad deal on the film financially. In retrospect I must have been inspired at least partly by my subject. Because I got my money — or most of it — up front. Feels like whistling past the graveyard. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Like any son who refuses to take responsibility for his own actions, I blame this all on my mother, Mary Louise, who is still alive and spry in Cleburne, working miracles in her kitchen every day. In 1975, I was finishing up the spring semester at the University of Texas at Austin when I received a call from her. She told me she had lined up a summer job for me at the geochemical company where my cousin worked in Houston. The gig was supposed to last three months. Obnoxious as usual, I told everyone I met that I would be there for only three months, and then I would get out of that humid hellhole and head straight back to my heavenly Austin. Almost 36 years later, I’m still here — in Houston, that is. That’s because I joined a cult. I became a journalist.

During that first summer in Houston, I began listening to KPFT-FM, to this day one of the damnedest radio stations I’ve ever heard — and as a radio junkie, I’ve listened to a lot of off-the-wall programming. There was Austin’s old KOKE-FM, home of the legendary Joe Gracey. And there was KFAD — one of the first so-call “underground” stations, which, strangely, was based in Arlington and Cleburne and was where my good friend Joe Nick Patoski spent a lot of time behind the microphone.

But KPFT was something else. It was run by an eclectic mixture of brilliant and magical radioheads, along with random whores, junkies, and alcoholics, as well as serious journalists who didn’t look at the world through the same eyes as mainstream media. It was the first time I’d ever heard of a listener-supported radio station — and it was nothing even close to the stodgy, buttoned-up product that continues to be broadcast by public station KERA-FM in Dallas. Instead, KPFT was as wild as the wildcatter city in which it was based. It was theater of the mind of the first order.

While I began as a listener, I soon joined that circus. During a fund-raiser, DJs asked for volunteers to come in and answer the phone, so I stepped up. At some point, they asked the phone volunteers if anyone would be willing to help the news department by ripping wire copy off the old Associated Press teletype machine. I raised my hand, and from that point there was no turning back. Soon I was handed a tape recorder and microphone and asked to go cover an event and write about it. One thing led to another, and within about a year or so, I was the news director.

From KPFT I went to KUHF-FM, the still-boring University of Houston station. However, the good thing about working for KUHF was that it was a National Public Radio affiliate, and by filing numerous pieces for NPR, I managed to land a full-time job with the network as its south-central states correspondent. After NPR, I spent six years as the night-shift police beat reporter at KTRH-AM, an all-news station. It wasn’t a great job, but I made lemons into lemonade by developing numerous law enforcement sources who would a great help to me in the future.

During my time at KTRH, I began dabbling in freelance print pieces for news organizations such as Newsday and Houston City Magazine. At Houston Metropolitan Magazine, one of my stories, with graphic details about the gang rape of a woman by a group of Houston high school football stars, got the editor, Gabrielle Cosgriff, fired. However, those pieces also got me hired as a staff writer for the Houston Press, the city’s alternative weekly.

And it was at the Houston Press that my path eventually crossed with that of one Steven J. Russell — con man and escape artist extraordinaire — who changed my life and the lives of many others.

In the summer of 1996, I read a Houston Chronicle story that was short on facts and details about a crook named Steven J. Russell, who had escaped from the Harris County Jail where he had been held following his embezzlement of almost $1 million from his employer. Even more intriguing was the fact that Russell had escaped by impersonating a judge when he called the county clerk’s office and had his own bond lowered. That kind of thing just doesn’t happen in law-and-order Harris County, the death-penalty capital of the world. I was sure there was more to his story than the couple of paragraphs the Chronicle gave it.

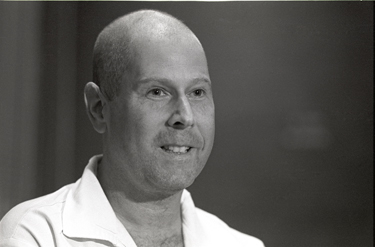

It took only a few days of running the standard traps to determine that indeed the small, balding, mousy-looking Russell had quite a past. The surface story was straight out of middle America: He’d grown up in Norfolk, Va., worked in his family’s produce business, volunteered as a reserve deputy for the local sheriff’s office, and played organ in church on Sundays.

But there was also a dark interior to Russell, which I would continue to learn about over the next seven years, as I researched that initial story, then others, and later a book. And the darkness developed early. It seemed to begin when he was 12, the day his parents, David and Georgia Russell, made a revelation that would change the course of their younger son’s life: He was adopted.

In another way, you could say that the strangeness began with his birth: As he would find out soon enough, the adoption was illegal, off the books, consummated with a wad of cash handed over in a hospital parking lot in September 1957 when Russell was five days old. Had he been born a scant minute earlier, he would have been a Friday the 13th baby. That, at least might have explained why, of four children, his birth parents had given only him away. He didn’t know those details then, but it was a subject that would obsess him for years to come.

As the news of Russell’s origins spread to younger members of his family, some of his cousins used the information to begin taunting Steven relentlessly. His retaliation moved straight past words to violence: He burned down a garage belonging to one cousin’s family. Then he set fire to a classmate’s jacket at school, causing extensive damage to a wall. And that led to 30 days in a hospital psychiatric ward, followed by nine months in the Hanover Boys Home. He was there for anger-management therapy. What he got was physical abuse by older, larger boys with their own criminal tendencies.

At 18, Russell joined the family produce business. In other circumstances that might have helped stabilize a young man’s life. In Russell’s case, it sucked him even deeper into a criminal world. At D.S. Russell & Sons, shady dealings were old hat. For years, Russell’s adoptive father had been conspiring with other Virginia companies to fix the price of produce sold to Virginia school districts. Steven Russell was going to fit right in.

Over the next several years, Russell established his all-American facade more securely. He volunteered as a reserve deputy for the sheriff’s department in Chesapeake, Va. He became close friends with the chief of police in Norfolk and married the chief’s secretary, Deborah. They had a daughter of their own, Stephanie. But beneath that placid surface, things were roiling.

For one thing, Russell used his status as sheriff’s deputy to get his birth mother’s name and address from confidential files. That’s when he found out that he had been the second of Thomas and Brenda Basham’s four children.

His birth mother still lived in the area, and Russell decided to confront her. At first she dismissed his claim that he was her son, but his persistence wore her down, and for a time Basham and her other children accepted Russell into their lives. That fairy tale was short-lived, however. It ended when Russell got in trouble with the law again.

His birth mother still lived in the area, and Russell decided to confront her. At first she dismissed his claim that he was her son, but his persistence wore her down, and for a time Basham and her other children accepted Russell into their lives. That fairy tale was short-lived, however. It ended when Russell got in trouble with the law again.

Even before that, not long after Russell joined his adoptive dad’s business, he convinced his father to up the ante on shady dealings by extending the price-fixing scheme to get contracts with the numerous U.S. military outlets in the Norfolk area. Trying to fool Uncle Sam turned out to be a disastrous idea.

The government had seen them coming and quickly issued indictments against officials with five Norfolk area produce companies. Most of the officials received plea deals, with some of them going to prison. Russell’s father also made a deal: He cooperated with the investigation, pleaded guilty to conspiring to rig bids, paid a $15,000 fine, and received a probated sentence.

Steven Russell, however, escaped indictment completely, giving rise to speculation that he too had rolled over for the feds. At that point, Russell decided it might be a good time for him and his family to leave town. He moved to Boca Raton, Fla., where, amazingly, he was hired as a patrolman specializing in DWI arrests for the Boca Raton Police Department. But after only a year, Russell was fired for repeatedly calling in sick while attempting to obtain another law enforcement job with the Florida Highway Patrol. He and his family returned to Virginia, but Russell would keep several key contacts in Florida.

Moving back to Virginia didn’t solve his problems, of course, because Russell carried his problems with him. His brief reunion with his birth family ended when Russell was arrested for stealing jewelry and computers, for which he received five years’ probation.

Another move was in order. The ever-resilient con man fell back on what he knew best — produce — and was hired by Sysco, a wholesale grocery company. The well-paying job required that he relocate to Houston. But when Russell set out for Texas, his wife and daughter stayed behind. He was headed for a new life in more ways than one.

The arts and entertainment scene in Houston was like nothing Russell had ever known. And it inspired him to unleash a side of himself that he had kept hidden for years. He began spending lots of time in Houston’s Montrose area, known, among other things, for its large homosexual population and abundance of gay bars. He’d done the circuit of anonymous bathroom sex in Norfolk area parks for years, but now he didn’t give a rat’s ass who knew he was gay — except, of course, for his wife and daughter.

The arts and entertainment scene in Houston was like nothing Russell had ever known. And it inspired him to unleash a side of himself that he had kept hidden for years. He began spending lots of time in Houston’s Montrose area, known, among other things, for its large homosexual population and abundance of gay bars. He’d done the circuit of anonymous bathroom sex in Norfolk area parks for years, but now he didn’t give a rat’s ass who knew he was gay — except, of course, for his wife and daughter.

Debbie and Stephanie joined him in Houston in January 1985, and for 15 months he managed to keep his sexual encounters with men on the downlow. In April 1986, however, returning from an evening of wine, cocktails, and sex with a younger man, he combined speeding with running from a traffic cop, hitting a railroad crossing at top speed, and rolling his Corvette numerous times — in the process breaking his pelvis in three places.

Over the ensuing months, Debbie nursed him back to health but also decided she’d had enough of humidity, Houston, and a husband she suspected was cheating on her. Before she and his daughter left for Virginia, Russell admitted to his wife that he was gay. They divorced but remained close friends.

After that, Russell bounced around the country, working in the produce industry. He also racked up indictments for state insurance fraud in Texas for faking injuries at various businesses and federal passport fraud. He fled to Florida again rather than face those charges, although warrants were issued for his arrest. But in Florida the clever Mr. Russell basically fell off the law enforcement radar while working in the tomato brokering business. He also found even more opportunities for crime — and another chance at love.

In Florida, Russell met and became infatuated with a tall, dark, and handsome man named James Kemple. For a time they led a grand life parading through south Florida’s best hotels, restaurants, and boutiques. That all ended when he received notice that he had been ordered to report to a federal prison in Oklahoma in March 1992 to begin serving his sentence for passport fraud.

Agonizing over his impending incarceration, on the night before he was to report to prison, Russell slipped into a serious funk and began mixing heavy doses of Xanax with large quantities of alcohol. The mixture proved almost fatal. He was hospitalized and placed on a suicide watch.

The next month, law enforcement officers escorted Russell from the hospital back to Houston to await transfer to the federal slammer in Oklahoma. But before the transfer occurred, Russell added a new item to his list of illicit skills: escaping from jail. It was the beginning of an amazing spree.

Russell was determined not to stay in jail — Kemple, long ago diagnosed as HIV-positive, was back in Florida dying of AIDS.

With another inmate’s help, Russell got his hands on some free-world clothes (though outlandish: red hot pants and a black tank top). With those and a walkie-talkie grabbed from a rack in sick bay, he passed as a worker, got a guard to open the right door, and walked out.

For the next two years, Russell and Kemple ping-ponged around the country, racking up an incredible record of scams (including high-level corporate jobs), arrests, and escapes: Stealing from a fast-food job in Florida. Pulling down $85,000 a year with NutraSweet in Chicago but also filing bogus expense reports. Insurance fraud in Florida and Philadelphia.

That part of the ride ended in Philadelphia, when Kemple bungled his role in an insurance scam and both men ended up in federal custody charged with bank fraud. Kemple, 28, was given a compassionate release on bond and went home to die in Florida in July 1994. And in federal prison in New Jersey, Russell went to work on a new scheme, with his late lover as inspiration: He would convince authorities he too was dying of AIDS.

An incarcerated doctor coached him on how to fake the symptoms. He stopped eating, lost weight, and became incontinent. He also used a prison typewriter to falsify lab reports.

“I was looking horrible on paper,” Russell once told me, laughing, during a prison interview.

Apparently near death, Russell petitioned federal authorities to drop the charges against him. They did — but there was still the little matter of felony fraud and escape charges in Texas. Back in jail in Houston, he found his next true love and began a chapter so absurd that fact indeed became stranger than fiction.

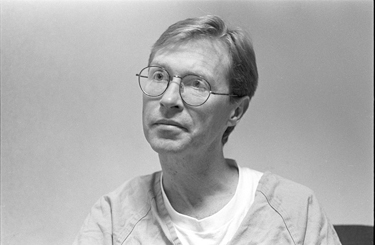

Convicted and sentenced to six months in prison, Russell again had to sit in county jail awaiting a cell in state prison. He made frequent trips to the Harris County Jail law library, where one day he noticed a short inmate trying to reach a book on a top shelf. The attractive little blond man was Phillip Morris, and he told Russell he’d been born on a Friday the 13th.

It was jailhouse romance at its finest. Morris, 35, confessed to Russell that he had spent a good deal of his time in the past as the boy toy of several strange men. Russell told Morris about his insurance scams and claimed to be an attorney. Russell got himself transferred to Morris’ cellblock and became his protector until Russell finally “caught the chain” to a prison cell in Huntsville. He promised Morris that once they were both paroled, he would take care of him.

And he did. Russell served the final three months of his sentence as a model prisoner, got out, got a job, and, posing as an attorney, expedited Morris’ parole.

And he did. Russell served the final three months of his sentence as a model prisoner, got out, got a job, and, posing as an attorney, expedited Morris’ parole.

With straight jobs never quite paying for the lifestyle Russell believed they deserved, he went back on the circuit as only a brilliant con and escape artist could: Get a job, make it more lucrative by cheating, go on the lam, get caught, escape, start over.

Manufacturing a bloated resumé, Russell was hired by North American Medical Management — as the company’s chief financial officer, pulling down a salary approaching six figures. The company handled the business affairs of private doctors and medical clinics.

Never a bean-counter, he actually surprised himself when, on his own, he discovered that NAMM was cheating itself out of money: Each month, clients poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into NAMM coffers, which the company was allowing to sit in non-interest-bearing accounts. When Russell discovered the situation, he switched the deposits into interest-producing accounts, generating close to $2 million for the company in just five months. And paid himself half of that as a reward. A NAMM official later told me in an interview that Russell was still one of the best CFOs he’d ever worked with.

But discovery was inevitable. He ran, was caught and jailed — and sprung himself once again by manipulating the Harris County jail phone system to route a call to the district clerk’s office, identifying himself as a judge and lowering his bond from $900,000 to $45,000. He arranged for a bondsman to post bail and was gone …

… And was caught in Florida, landing back in prison, this time in Texas’ Estelle Unit near Huntsville. Where he lifted a doctor’s ID badge and helped himself to a stash of green felt-tip markers in art class. What can you do with those two things? If you’re Russell, you can extract the ink in a tub of water, turn a white prison uniform into green medical scrubs, attach the stolen ID, walk out, and catch a cab.

Of course, if you’re Russell, you also hook up with your lover in Florida again, get caught again, go back to state prison — and turn back to a classic in your playbook: the inmate dying of AIDS. This time, in addition to semi-starving yourself and forging medical records, you arrange a “special needs” parole to a private medical facility, sealing the deal by placing yourself in a calculated but dangerous coma with an overdose of stashed drugs. Safely ensconced in a San Antonio-area nursing home, you come out of the coma, impersonate a doctor, get yourself released to help with experimental research, then report your own death.

Of course, if you’re Russell, you also hook up with your lover in Florida again, get caught again, go back to state prison — and turn back to a classic in your playbook: the inmate dying of AIDS. This time, in addition to semi-starving yourself and forging medical records, you arrange a “special needs” parole to a private medical facility, sealing the deal by placing yourself in a calculated but dangerous coma with an overdose of stashed drugs. Safely ensconced in a San Antonio-area nursing home, you come out of the coma, impersonate a doctor, get yourself released to help with experimental research, then report your own death.

Months later, a state prison system fugitive tracker named Terry Cobbs found himself looking at a photo he couldn’t believe. It was that of a man posing as an attorney. But it was also the face of Russell, whom Cobbs had helped put away, allegedly for life, several months earlier. Seems Russell, who could have stayed free forever, since he was supposedly dead, needed the bar card to visit Morris in Dallas County jail.

This time they found Russell in Broward County, Fla. Jailed there, he got his hands on an unrestricted phone and called me at the Houston Press.

“This was a masterpiece, wasn’t it?” he asked, laughing.

During the two years (it seemed like more) that I covered Russell for the Press, his exploits generated two cover stories and several smaller news pieces. I’d always thought I should write a book or a screenplay about the man the Press headlines called the King of Con. But attempting to meet the paper’s story quota was about as much as I could deal with then. So it wasn’t until I received a call from another journalist that I finally got off my ass and got busy.

The call, in early 2001, was from Mark Schone, then an editor with Spin Magazine in New York. Schone told me that he had seen my stories on Russell and was planning to write one himself for Spin. He wanted my help getting in touch with him.

Now usually, I like to think I’m a pretty agreeable guy. But for some reason, on this day, Schone’s words got my back up. I told him that I had invested a great amount of time covering Russell, that I intended to write a book about the guy, and that if anyone was going to write about him, it was going to be me.

Schone, author of Son of a Grifter, graciously replied that in that case he would gladly send my clips that he had collected to his New York publishing agent, Peter Steinberg. Humbled and embarrassed, I thanked Schone and asked him to, yes, please send my clips to your agent.

Not long after that, Steinberg called: He was very interested in representing me. After several false starts, I put together a book proposal that he liked. And in August 2001, Steinberg struck a deal for me with Miramax Books. Yes, that Miramax.

I Love You Phillip Morris was published in June 2003, but it didn’t do much. The promised publicity tour never materialized, but I did give interviews to numerous radio stations around the country while I sat at home in my pajamas. There was also a lovely book signing at the new and sparkling Hobby Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Houston.

Several months before the book was released, movie rights had already been optioned by Mad Chance Productions in Los Angeles — a deal engineered by my West Coast agent (I like saying that), the wonderful Marti Blumenthal. But I didn’t hold my breath. Other stories of mine had been optioned before, but nothing ever came of it.

This time, though, Mad Chance assigned two established Hollywood screenwriters — John Requa and Glen Ficara of Bad Santa fame — to produce a script. Over the next few years, Mad Chance renewed the option two or three times, and EuropaCorp stepped up to bankroll the film, which was said to have a tiny budget of around $13 million.

Then in May 2007, Mad Chance notified me that Jim Carrey had committed to the role of Steven Russell. Ewan McGregor had agreed to play Phillip Morris. While that put a nice bounce in my step, things got even better — especially monetarily — when they actually began shooting the movie in 2008. I didn’t splurge or go on a bender, but I did put a down payment on a small house in The Heights area of Houston, close to downtown. I also bought a pair of hand-made cowboy boots from Rocky Carroll, bootmaker to the stars and President George W. Bush.

That October they even flew me to New Orleans, where much of the film was shot, for a cameo role. My good friend Janet Meyer tagged along as my entourage, and we did New Orleans up right — oysters, gumbo, soul food, and late-night gambling and carousing. One evening we were taken to dinner by the costume director, who was dressed in a kilt. But it was New Orleans and nobody gave a fuck. Joining us for dinner was the real Phillip Morris, who was also there for a cameo role. Morris had not cared for my book, which made him out to be not as innocent as he claimed, so dinner got off to a somewhat awkward start. But after a couple of Dewar’s, I really didn’t give a damn what he thought of the book. Actually, I didn’t give a damn even before the scotch and still don’t for that matter.

On the set, in an east New Orleans courthouse that had been abandoned after Hurricane Katrina, I was taken to a trailer where makeup artists powdered my bald head. Then I was outfitted with a judge’s robe and taken before the cameras. I was filmed banging a gavel and uttering a few sentences. What ended up in the movie was just a quick shot of me looking very judicial.

Morris was also on the set, playing a non-speaking role as Russell’s attorney. Due to Morris’ inability to avoid looking into the camera, it took forever to complete the scene. At one point I even fell asleep.

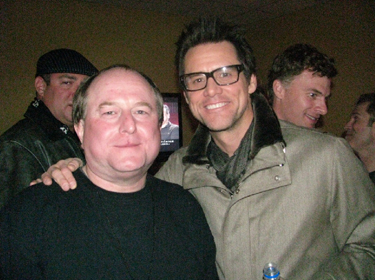

During a break in the shooting, Carrey came over and introduced himself. All I can tell you is that he is very tall and very nice. Even though I hadn’t brought it up, he took me aside and told me that he had heard of a series of personal setbacks I had experienced the previous year. Carrey, who at one point lived in a car in his native Canada when his father lost his job, told me quite sincerely not to get down about those problems and that everything would eventually work out. Like I said, a very nice guy. He would later give me a shout-out on David Letterman’s show.

During a break in the shooting, Carrey came over and introduced himself. All I can tell you is that he is very tall and very nice. Even though I hadn’t brought it up, he took me aside and told me that he had heard of a series of personal setbacks I had experienced the previous year. Carrey, who at one point lived in a car in his native Canada when his father lost his job, told me quite sincerely not to get down about those problems and that everything would eventually work out. Like I said, a very nice guy. He would later give me a shout-out on David Letterman’s show.

In January 2009, the film, bearing the same title as the book and with me getting a full credit, received great reviews at the Sundance Film Festival. Despite changes to the chronology and omission of some facts and details, I thought the film was wonderful and could not have been happier with the job that Requa and Ficara had done.

Everyone seemed sure that we would soon be picked up by a distribution company. But the offers didn’t come. Finally, after months of waiting, Mad Chance struck a distribution deal with Consolidated Pictures Group. A release date was set. And then another and another. Indeed, while the film was playing all over Asia and Europe, the U.S. release was delayed again and again.

In the meantime, I had attended a film festival in Nashville where I Love You Phillip Morris was featured. Along with Requa and Ficara, who had also ended up directing the movie, and an assistant producer on the film, I took part in a panel discussion during which we explained how the film had come together — that is, if you can say that a film that still wasn’t playing in the U.S. had come together.

However, during that discussion, the assistant producer let it slip that the film was actually produced on a $17 million budget. His words immediately grabbed my attention seeing as how my contract called for me to be paid on a sliding scale depending on the size of the budget. I had been paid based on a $13 million budget. Any budget over $15 million meant that I was owed more money — which I pointed out to the assistant producer on stage. He did not reply, nor did we spend a lot of quality time together during the remainder of the festival.

When my attorney contacted Mad Chance’s attorney, the reply, essentially, was that my attorney and I were a couple of nitwits — which is an extremely unfair evaluation of my attorney. The Mad Chance lawyer also threatened to take legal action against us. We are still pondering our options.

Meanwhile, Mad Chance and Consolidated remained locked in a stalemate over the U.S. release of the film. In some publications and on some web sites, I Love You Phillip Morris became known as the film that would never be released. Finally, Mad Chance took Consolidated to court and severed their relationship.

Luckily (at least somewhat), the distribution rights were obtained by Roadside Attractions. And while a firm release date was finally set, there was not much more. The little promotion the movie was afforded came in the form of a few billboards and even fewer commercials. The biggest push the film received was from Carrey’s appearance on Letterman, who absolutely gushed about the movie and told Carrey it was the best performance he had ever given.

Fortunately for me, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston hosted a wonderful sneak preview of the movie, followed by a panel discussion featuring me, Cobbs, and former prosecutor Terry Jennings, who is now a state appellate court justice.

The next morning I was still enjoying the afterglow of that event when I received a phone call warning me that Roadside officials were extremely angry with me and demanded an apology — for what I was never quite sure. It might have something to do with the possibility that during the Q&A at the museum, I might have given guests the impression that Morris was not the innocent victim he had been portrayed as in the movie but instead was a gold-digging little punk who had been up to his ears in Russell’s embezzlement at NAMM. They threatened not to pay my way to the NYC premiere, but ended up paying about half.

Still, despite critical acclaim, the film hasn’t done well. Its run was short, and if you blinked, you missed it. (The movie is due out on DVD in April.) Both Carrey and McGregor had given Oscar-worthy performances, but, sadly, their efforts pretty much went unnoticed. Requa and Ficara were finalists for the best adapted screenplay award from the Writers Guild of America. But the main thing that stood out was the scoreboard. As of this month, according to International Movie Database, the film had still to break the $2 million dollar mark in U.S. receipts, although it reportedly pulled in close to $20 million at foreign box offices.

But I can’t complain much. I still have my house, and I still have my boots. Nor has the movie hurt my marketability. I’ve been interviewed numerous times by various media outlets (mostly not in my pajamas), which doesn’t pay much but boosts my profile and my hopes of getting another book published. I already have a proposal in to my literary agent, Steinberg, and he likes it. Maybe we can catch lightning in a bottle a second time. I’ve also made a few bucks writing pieces like this on a freelance basis.

As for Steven Russell, I continue to correspond with him as he serves his life sentence in a solitary confinement cell 23 hours a day in the state prison system’s Michael Unit near Palestine in East Texas. Last I heard, Morris was still a free man living in Arkansas, which may be sentence enough. I saw him at the NYC premiere, but we didn’t speak. What a shame. We had so much catching up to do.

By now, though, the words I Love You Phillip Morris are starting to give me a headache. It’s been a great run, but this is my last story about this picture show.

Author and journalist Steve McVicker lives in Houston.

[…] To Hollywood And Back – After all, the film is based on the story of one of God’s purest con men, an artiste in the field of walking off with other people’s money, a master of illusion so skilled at escape that sometimes it seemed as if he must have made cell doors simply … […]