“It’s nice to get some attention from the hometown press,” said Feehan. His civic pride is reflected in the name of his production company, The Fort Films, which he formed in the wake of Mandy Lane with Amanda Micallef, another Fort Worth native working in Hollywood. Though his offices are in Los Angeles, he talks about developing a TV show set in Fort Worth, a drama influenced by Sons of Anarchy and Friday Night Lights. “I think Fort Worth has a great visual palette,” he said. “You have the contrasts between the Stockyards and downtown, the East Side and the homes on the West.”

Feehan grew up in one of those homes on the West Side. His family moved to Fort Worth from Houston in 1978, when he was 10. He was born on Halloween, and with the whole country dressing up for his birthday each year, young Chad happily joined in.

“I would make the most elaborate costumes for him,” said his mother Sharon, who also remembered Chad’s fascination with pro wrestling. “He had a billion characters. He’d spend hours inventing these new wrestling personas.” Though Chad never got into in the pro ring himself (undoubtedly to his parents’ relief), he did join the Fort Worth Country Day school wrestling team and played baseball and football.

His parents also nurtured his love of movies, frequently taking him and his sister to the Telluride Film Festival. Feehan mentions Spielberg and John Hughes films as cinematic influences, but he also reverently cites Reservoir Dogs, El Mariachi, and other films from the American independent cinema movement that boomed during the late ’80s and early ’90s, when he was coming of age.

Even as a teenager, Feehan wanted to make films, but some valuable advice from a Hollywood heavyweight caused him to hold off. Feehan’s father Dan, the CEO of Cash America Inc., attended a business lecture by film producer Peter Guber, the man behind such hits as Flashdance, The Color Purple, and Rain Man.

After Dan mentioned his son’s interest in making films, Gruber counseled him to tell Chad to study English literature in college and leave serious cinematic studies for graduate school. (“Movies start with a story.”) Chad duly obtained a bachelor’s in English from the University of California at San Diego, spending one summer studying literature at Oxford and another taking film courses at the nearby University of Southern California.

For graduate school, Feehan looked into all of the “big four” American film schools: USC, UCLA, New York University, and the American Film Institute. He chose AFI, the alma mater of such filmmakers as Terrence Malick, David Lynch, and Darren Aronofsky.

“AFI operates on a conservatory model,” explained Feehan. “You’re not trapped in an academic bubble. You’re in the classroom Wednesday through Friday, but you’re shooting Saturday through Tuesday.” When it came time to choose a specialty, Feehan opted to train as a producer rather than as a director or screenwriter. “I felt it was the safest choice,” he remembered. “It would give me more control. It seemed impractical at the time to direct.”

Initially choosing the business side of filmmaking over the creative side reflected Feehan’s conflicting desire for financial stability while pursuing a career in the arts. “The Graduate affected me most when I was younger,” said Feehan. “Ben [Dustin Hoffman’s character] wanted something different out of his life, and I felt like I didn’t want to be a doctor or a lawyer.”

Such pressure came mostly from within.

“A lot of young men tend to fall in step with their fathers’ career paths,” said Dan Feehan. Chad “was determined at an early age to do something different. I think he felt the pressure of measuring up [to my success]. Young men have that issue with their fathers.

“We’ve tried to raise both our kids to believe that happiness isn’t necessarily reflected in a big house or a big salary,” he said. “Go do something you’re going to be happy doing. That’s what success in life is.” Despite the geographical separation, Dan and Sharon Feehan remain close to Chad and to their daughter Cari, who lives in San Diego.

Everyone who knows Chad Feehan testifies to his single-minded focus. “If there’s one word that describes Chad, it’s intensity,” his father said, “Everything he does, he does it with every fiber of his being, whether that’s school or football or movies.”

Jacob Forman, the screenwriter on All the Boys Love Mandy Lane, put it in different terms: “Chad drinks more Diet Coke than anyone I’ve ever met. He’s direct, fiery, passionate, a bit stubborn, but always a good listener,” he said.

Micallef simply said, “Chad is very good at not letting the ball stop.”

He’d need all that tenacity to sustain him as he watched his biggest success turn into a unique sort of disaster.

********

All the Boys Love Mandy Lane began at AFI. Feehan’s thesis required him to submit a business plan, budget, and shooting schedule for a feature film. Fellow students Forman and Tom Hammock were working toward degrees in writing and production design respectively, and their theses required finished scripts and designs for an imagined feature film as well. The three decided to pool resources and work on the same project.

The story’s setting was inspired by Feehan’s adolescent memories of vacationing on wealthy friends’ ranches in central Texas. However, he had no interest in making an exercise in nostalgia. “A horror film is a safe bet,” he said. “And I felt I could get a ranch [to film on] for little money.”

A New Yorker, Forman needed some help getting into the right mood for writing the script. “I watched a lot of horror movies, but I also watched a lot of Texas movies,” Forman remembered. The crystallizing moment came when he saw Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 coming-of-age film The Last Picture Show.

“There’s a scene where [Cybill Shepherd’s character] is standing by the pool and has to choose whether she wants to be an outsider or one of the cool kids. That made me realize what I wanted the film to be,” Forman recalled. Indeed, the opening scene of Mandy Lane takes place by a swimming pool at a house party, when a villainous nerd (played by Michael Welch) tries to talk a dumb jock into jumping off the roof into the pool to impress Mandy, a scene with greater psychological complexity than most horror films possess.

The film might have stayed on the page as a student project, but Feehan didn’t want to still be working as an assistant when he graduated from school. (Forman described the experience as Chad’s “typical white-knuckle style.”) While serving internships together at Cruise/Wagner Productions (the production company owned by Tom Cruise and his producing partner Paula Wagner), Feehan and Forman blanketed the town with their script.

“We didn’t know that that isn’t how it’s done,” said Feehan. Nevertheless, their approach worked — they found some workshop classmates who had started a production company called Occupant Films and were looking for their first project. Their budget necessitated some changes in the script: An early draft set in the 1950s had to be discarded to save the costs of period costumes and décor. For similar reasons, a large car accident was dropped from the script in favor of the scene on the roof.

To direct the movie, Feehan brought in AFI classmate Jonathan Levine. “His vision was in sync with ours,” said Feehan. “We wanted to meld together the movies that we loved — 1970s slasher flicks and John Hughes movies.”

“I was stuffing envelopes at a talent agency” when Chad approached him, said Levine. “The script was really fresh. It was a great opportunity.” Levine’s own breakthrough came last year when he directed the cancer comedy 50/50, which won strong reviews and landed on several critics’ lists of the best films of 2011.

Playing the title role in Mandy Lane was Amber Heard, a then 20-year-old Austin native in her first starring role, having played some small parts in North Country and the film version of Friday Night Lights. Since then, she has played the female lead opposite Nicolas Cage in Drive Angry and Johnny Depp in The Rum Diary, as well as on the short-lived NBC TV show The Playboy Club. (She also caused a minor flurry when she quietly went public with her lesbian relationship.)

Heard was unavailable for comment, but she described the Mandy Lane role in a 2008 interview for Rottentomatoes.com. “I found this script and said, ‘Whoa, I want this movie, I have to do this.’ … [The script] kind of mocks you a little bit and your expectations.”

The film indeed plays with the conventions of teen horror films, which always seem to involve a virginal girl taking on a faceless killer who butchers her sexually active friends.

Mandy Lane is much more neatly directed than most other movies of its kind. Its high production values on a low budget (around $750,000) and its twist ending are probably what won it such a following, even if the twist isn’t that well thought-out.

The passage of time has dented the film, too, especially since its ground-breaking aspects have been duplicated by other films. “[Last spring’s] Scream 4 basically did everything we did,” said Feehan ruefully.

Even before Mandy Lane’s premiere at the Toronto festival, it had won Feehan his break. An early copy made its way to powerhouse talent agency Creative Artists Agency, which signed Feehan to its roster, where he remains today.

The film played as part of the Midnight Madness program, the festival’s outlet for often-violent thrillers and horror flicks. Mandy Lane had obtained a prime location in a packed theater built to seat 1,300 people. “I didn’t know what to expect,” said Feehan. “We got to the theater and saw a line extending two city blocks to get in.”

“It was an amazing night,” said Micallef, who had worked on the film in an unofficial capacity. “I saw CAA agents grabbing Chad. It was electric. It was some of the most fun I’ve ever had.”

An experience Feehan described as “eye-opening” was about to get even more so. When the Q&A session with the audience was over and Feehan was leaving, CAA representative Brian Kavanaugh-Jones came up and gripped his arm. He said, “Harvey wants to make an offer.”

He was referring to Harvey Weinstein, who had brought American independent film into the mainstream through his company, Miramax Studios. At the time, Weinstein had just acrimoniously parted with the Disney Corp., which had bought up Miramax, the company Weinstein founded with his brother Bob.

Since 1992, Miramax’s downmarket arm, Dimension Films, had filled the company’s coffers by making and releasing lowbrow genre movies such as the Scream films. Weinstein had lost the rights to use Miramax’s name when he broke with Disney, but he still retained Dimension Films for use as part of his new studio, The Weinstein Company. All the Boys Love Mandy Lane would have fit perfectly into Dimension’s slate of releases.

In a courtyard behind the theater in the small hours of the morning, Mandy Lane’s producing team negotiated a sale with Weinstein and his representatives. The two teams never spoke directly, staying on opposite sides of the courtyard while one of Weinstein’s workers ran back and forth with a legal pad with figures scribbled on it. The morning ended with Feehan and his fellow producers $3.5 million richer and a deal in place to release the film worldwide, though no one bought any sports cars with their share of the money.

“Most of the money went to the financing company,” said Feehan. “Most of us used our portions to pay our student loans, rent, put food on the table.”

But the money did make possible one important luxury: “We weren’t forced to get a 9-to-5, so we could wholly focus on our filmmaking careers,” he said.

********

While the film was eventually released in 30-plus countries across Europe and the Middle East, it has yet to play in North America, outside of a few festivals. Some have speculated that Weinstein was looking to cut losses after a string of its horror films (including Wolf Creek, Pulse, Black Christmas, and Grindhouse) flopped at the box office. Then again, perhaps it had nothing to do with horror — the mogul was notorious for souring on films he had acquired and letting them sit on the shelf for long periods. He couldn’t be reached for comment for this article.

Whatever the reason, in the summer of 2007, Weinstein quietly sold the rights to the film to Senator Entertainment, a German firm that was looking to establish a beachhead in the North American market. Mandy Lane would have been its first U.S. release, set for early 2008.

That release was then canceled, as the company instead chose the Bret Easton Ellis adaptation The Informers for its first American release, and it promptly failed at the box office. The company then reorganized with a new focus on marketing German films to German audiences. Mandy Lane was still on the books, and Entertainment Weekly reported a July 2009 release date, but that date came and went with no news.

In August 2009, Senator shuttered its American operations. One more tease came when the film screened at Comic-Con in July 2010, with Levine and Heard in attendance. Heard hinted that a distribution date was about to be announced, but none was forthcoming.

Long before that, the film’s on-again, off-again travails had become a joke. (“I wanted to see Mandy Lane when she was young and sexy, not an old hag,” cracked the horror fan website Bloody-Disgusting.com in 2008.) Much like its title character, Mandy Lane’s out-of-reach quality added to its mystique and allure, turning it into something of a cause célèbre on websites such as FearNet and Cinematical. Senator Entertainment did not respond to inquiries about the film’s status.

Through it all, Feehan didn’t rail in the press about the unfairness of it all or join an ashram or gain 30 pounds and grow a beard. Instead, he calmly switched over to writing and directing films.

“I wanted to write something I could make quickly on a small budget,” he said. “The only thing I knew how to do was make another movie.” The result was Beneath the Dark.

********

To make Beneath the Dark, Feehan first formed The Fort with Micallef, whom he had known since they were schoolchildren. After working on Texas-made films in the mid-1990s, Micallef (the daughter of Reata Restaurants co-founder Al Micallef) had moved out to Los Angeles to house-sit for a friend and never left, learning the ins and outs of development and optioning scripts. When Feehan also moved to Hollywood, she rented him office space, and a partnership was born.

“She kept us from making a lot of mistakes that first-time filmmakers often make,” said Feehan about her work on Mandy Lane. “You’re only as good as your collaborators.”

Micallef is equally effusive in her praise: “Chad’s a born leader,” she said. “He’s extremely generous, and he always wants to know what someone else thinks. We have enormous mutual respect for each other.”

Together they turned Feehan’s script, originally titled Wake, into a thriller about a young couple (played by Josh Stewart and Jamie-Lynn Sigler, the latter famous from her regular role on TV’s The Sopranos) who find themselves marooned at a desolate 1950s-vintage roadside motel in the California desert. The hermetic environment turns out to be a platform for an ambitious attempt to blend supernatural elements with a moral lesson on the consequences of one’s actions.

A prominent role went to Angela Featherstone, a longtime character actor who had met Micallef at an earlier premiere. Working for a first-time director presented no challenge for her. “Chad’s a natural,” she said. “He’s always the same. You never ask ‘What’s going on with Chad today?’ I show up at work and I know what’s expected of me.”

Steadiness and sensitivity would be important qualities in shooting a scene that occurs late in the film when Featherstone’s character is assaulted. “Chad and Amanda asked me when I wanted to shoot the scene, whether I wanted it to be the first thing I shot or the last thing. That was important to me,” she said. “I knew that Chad would protect me, that my safety was important to him.”

Beneath the Dark was bought by IFC Films and given a limited theatrical release in November 2010. The film received poor reviews, and Feehan admits that the critics might have been justified. “I was trying to meld genres. It’s difficult to pull off. I may have pushed too far,” he said recently. Nevertheless, he was happy just to see one of his works actually reach a paying audience. “I hadn’t directed anything since I was 18,” he said. “It was incredibly gratifying.”

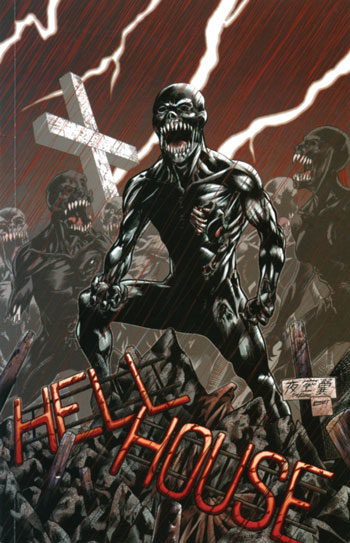

He also collaborated on Hell House, a graphic novel whose story originated with Ryan Dixon, a fellow intern at Cruise/Wagner. After Mandy Lane’s success, Dixon approached Feehan with an idea for a horror comic built around “hell houses,” the fundamentalist Christian haunted houses depicting what their organizers view as sinful behavior.

“I did some research. I was both fascinated and appalled,” said Feehan, who said he was not raised with religion but believes in “some sort of God.”

The project was originally written as a screenplay, but when Jesse Garza, the vice-president of Dallas-based Viper Comics, met with Feehan, the filmmaker pitched the script as a possible graphic novel.

“When writing graphic novels, you have to write what you see on every page,” said Feehan. “There’s only a few panels to work with. We wound up cutting out a lot of the script.”

How does he feel about the result? “I won’t do another graphic novel,” he said flatly. “I enjoyed it, but it’s difficult. I think the story suited the format. I just wish [the ideas under discussion] had been more elevated.”

In the meantime, he has branched out into music videos, directing the video for “Heart Song,” by the hard-rock band Automatic Loveletter. Taking inspiration from Rob Zombie’s horror movies, Feehan gave the video the look of a low-budget 1970s exploitation flick, with its barn setting, grainy visuals, and extensive shots of lead singer Juliet Simms wandering around in a bikini. Automatic Loveletter’s fans were deeply divided, but the band was pleased with the final product.

“Going with Chad was a no-brainer,” said Simms, who is currently a contestant on NBC’s musical talent show The Voice. “I loved his vision, concept, and old-school approach. The gritty, dirty rock ’n’ roll imagery was exactly what the song called for.” She added that she’d like to work with him again.

The biggest recent accolade for Feehan came late last year when his script for a Southern Gothic thriller called Beyond the Pale landed on The Black List, an annually published list of the best unmade scripts in Hollywood. Making the list is often a stepping-stone toward getting a film made: The Hurt Locker, (500) Days of Summer, and Juno all had previously made the list.

Based on a 2006 novel called Twilight by the late William Gay, Beyond the Pale is about a young Southerner who flees through the wilderness from a hired killer. Feehan first heard about the book from his reader. (Screenwriters, producers, studios, and stars often hire people to read novels and other sources for them and advise what material might be adapted into a film.) “My reader said he liked [Twilight], but it couldn’t be made into a film because of the necrophilia,” said Feehan. “I forgot about it, and then I was going home for Christmas in 2009, and I read an article where Stephen King called it the best book he read all year. I got it and read it in one day.”

Taking advantage of the Hollywood writers’ strike, Feehan was able to buy the film rights to the book on the cheap. Now he’s in negotiations with an overseas company to finance the production.

While Feehan would still like to see Mandy Lane released from its purgatory, his other projects have helped him make peace with his first film’s status. Critical though he is of his work, Feehan described himself as “super-proud” of the film.

Forman pointed out that despite the popcorn crowd never having had a chance to see it, the film’s initial success has still worked as a calling card for those who made it.

Feehan’s attitude toward his Hollywood career makes him sound like the athlete he once was, rather than the wrestlers he dressed up as on those long-ago Halloweens. “Filmmaking is about persistence and hard work, not just talent,” he said. “Filmmaking is a marathon, not a sprint.”

[…] Festival, SXSW, and the Sitges Film Festival in Spain. The film was also Fort Worth, TX native Chad Feehan’s thesis project while finishing up his final year at AFI in Los […]