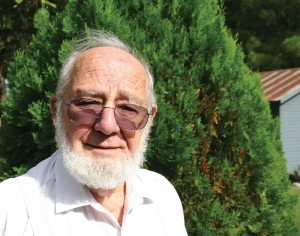

Another summer is winding down –– number 87 for Robert Platt. Seasons come and go rather uneventfully these days. Platt retired as a college professor about 25 years ago, and he then spent 16 years owning and operating the bookstore Books, Etc. in the Stockyards. But in 2009 he pulled down that shingle and settled into real retirement. Now he pretty much hangs around the house with his wife of 67 years, Ruth, reading books and newspapers and watching news shows on television.

He recalls many great summers. The Platts raised four sons, and the hot months were filled with vacations, sports, and any number of activities. Still, the summer that stands out most goes back all the way to 1961. That’s when Platt, a campus minister, helped open the doors of Texas Tech University to African-American students, who’d been forbidden from enrolling ever since the school opened in 1923.

His civil rights stance cost him his job at the university and prompted backlash from at least one church member, who called him a communist. But it remains a proud moment.

“Tech had a very long period when blacks couldn’t go there,” Platt said. “They attributed it all to the fact that [segregation] was in the constitution, but it wasn’t.”

Looking back, Platt sees many events occurring early in his life that put him on track to advocate for African-Americans. He was born in the summer of 1928 in Utica, N.Y., at the peak of the Roaring ‘20s. His mother died seven months later, and his father gave him to relatives. The baby was deaf in one ear and had a slightly defective heart but was otherwise healthy.

The next year, the stock market crashed, leading to the Great Depression. Platt lived in a small house in the working class town of New Mills, N.Y. His aunt would become “Mom,” and his much older cousins became his brothers and sisters. But it was grandfather James who stole his heart. Platt and James, in his 60s at the time, became best buddies.

Platt’s biological father, Robert Platt, remarried and returned a few years later to fetch his son. Poor James became despondent after the boy left. Fearing for the grandfather’s sanity, the family asked Robert to return the boy, which he did. Platt was never legally adopted but lived with his surrogate family until he completed high school.

Grandpa James cheered up considerably with Platt’s return, and they spent most days hanging out. James was quiet and gracious, but at times “he could become quite indignant about social injustices,” Platt recalled.

The family’s cramped quarters and financial uncertainties created worry in the young boy’s mind, exacerbated by the country sliding into World War II. He developed a deep sense of empathy for people who endured suffering.

“I have never really escaped from either the time or place of these formative years,” he said.

Every other summer while growing up, Platt took a train to visit Robert, who lived on a cotton farm. Two African-American families lived in houses on the farm and worked the fields. They were the first black people Platt had ever met.

“Whenever I went to Tennessee, I always played with black kids,” Platt said. “We played games and ran around, had ice cream, and did all the things kids do.”

After high school, Platt enlisted in the Navy but was rejected due to his deaf ear. He attended a Christian college, met his future wife, and enrolled in a seminary. By 1958, he and Ruth and their four children were bound for Lubbock in a Studebaker station wagon with all their belongings piled into a U-Haul trailer. Platt had accepted a job as campus minister at Texas Tech.

First Christian Church was a block away from campus, and students received credits for attending religious classes that Platt taught at the church. In 1961, Platt began teaching an introductory philosophy course on campus.

That same year, an African-American minister at the Mount Vernon Methodist Church in Lubbock complained about Tech’s refusal to enroll black students. Platt heard through a mutual acquaintance that the Rev. M.T. Reed was planning to push the issue.

Attempts to integrate public schools during that time had often prompted protests, violence, and National Guard involvement in numerous cities across the South. Platt worried that the same thing would happen in Lubbock. Platt visited Mount Vernon Methodist bright and early on July 17, 1961, introduced himself to Reed, and asked if it was true that Reed was going to seek help from the national NAACP to force integration.

“Instead of answering me verbally,” Platt said, “he opened a desk drawer and pulled out two envelopes with petitions enclosed, addressed to the NAACP national office.”

Two African-American applicants who’d been previously denied admission to Texas Tech had started petitions to force the school’s hand.

“It would have been a mess,” Platt said, fearing how West Texas rednecks would react to black out-of-towners flooding into Lubbock demanding changes. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in 1954 that state laws requiring segregated schools were unconstitutional. Change, however, was slow to come.

“The Brown vs. the Board of Education verdict had been issued in Washington, D.C., but D.C. was a long way from Lubbock,” Platt said.

Reed was leaving that morning on a five-day trip to New Orleans and had planned to mail the petitions on the way to the train station. Platt asked Reed to hold off on mailing the letters. He wanted to come up with another plan.

“Lubbock might be the next Little Rock,” Platt warned, referring to the Arkansas city that erupted in intimidation and violence after attempts to integrate schools there.

Supposedly, Lubbock Mayor David Casey was sympathetic to the black cause, and Platt vowed to visit him. Sure enough, Casey said he would back any efforts to integrate Tech.

“He was pushing for it all along,” Platt said.

The main obstacle was the university’s board of regents.

The next day, Platt flew to Chicago for a national conference of campus ministers. Arriving back in Lubbock a couple of days later, he was greeted by a big headline in the local newspaper: “Tech to Open Up Doors to Negroes.”

Under pressure from the mayor, the board had reversed its longstanding tradition, although one of the board members had resigned in protest. A Lubbock reporter had credited Platt as an intermediary in changing the admission policy. But the reporter had mistakenly identified him as a “Negro minister,” probably assuming that any local minister fighting for integration must have been black.

Though a husband and father, Platt said he wasn’t worried about sticking his neck out.

“I was sure it would come out alright in the end,” he said. “I’m optimistic. I don’t want to be to be overly religious about it, but I trust God.”

His children weren’t really aware of what was playing out in Lubbock back then, but they’d seen many examples of Robert and Ruth Platt being selfless.

“Mom and Dad have always been active in civil rights and equal opportunity struggles,” youngest son Tim said. “They were active in the timeframe when civil rights wasn’t a popular train of thought. They’ve been that way all their lives and still are.”

After Tech opened its doors to black students, Platt resumed teaching philosophy –– until a university official paid him a visit after the second day of class.

“You’ve been taken off teaching,” the official said. “I don’t know why.”

“I knew why,” Platt said.

Rather than complain or sue the university, Platt drove 27 miles to South Plains College in Levelland and got a teaching job.

“I came out better for it,” he said. “I got this other job the next day. Things worked out. My life has been very blessed.”

In the late 1960s, Platt began teaching at Tarrant County Junior College and living in Fort Worth, where he’s remained ever since. These days find him “just puttering around.”

But every once in a while he’ll revisit his Tech yearbooks and news clippings and recall that special summer of 1961 when he played a minor role in making a great societal change.

Good work Mr. Platt. God bless you Sir.