Gustave Caillebotte is the forgotten man of the Impressionist movement. This artist counted Monet, Degas, Renoir, and Pissarro among his friends and supported them by buying their artworks, but for a number of reasons, he didn’t achieve the high status that they did. He didn’t live long, for one thing, dying of pulmonary congestion at age 45. He wrote few letters and kept no journal, so much of his private life is a mystery to us. The scion of a wealthy family in the textile industry, he didn’t sell his paintings because he didn’t have to make a living. And he spent his last years in retirement in the French countryside away from his native Paris. The current exhibition at the Kimbell Art Museum, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, seeks to restore the artist to his rightful place as a major painter of his time, and it makes a rather convincing case.

Any discussion of Caillebotte must begin with his one famous painting, “Paris Street; Rainy Day.” When Walter Chrysler bought this large street scene in 1955 and brought it back to America, the French government, famous for jealously guarding the nation’s cultural treasures, took no notice. This arresting composition of fashionable Parisians with umbrellas is one of the crown jewels of the Art Institute of Chicago. You can admire the visual power of the composition or the technical skill that goes into depicting the rain-slicked cobblestones. You may not know that Caillebotte was painting an entirely new neighborhood, as the French government’s urban renewal project after the Franco-Prussian War had turned what had been a barren field into a bustling residential quarter for the upper-middle class.

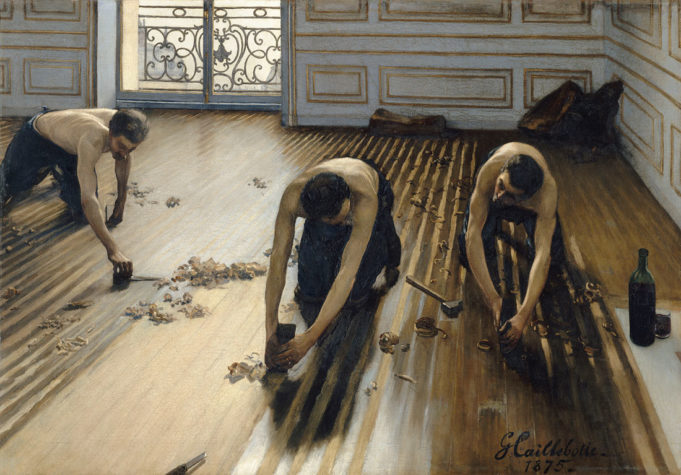

Caillebotte had trained in the established tradition of academic painting, but he kept chafing against its strictures. His “The Floor Scrapers” was submitted to and rejected by the Salon because its three shirtless male figures were not classically proportioned and dressed as mythological heroes but rather depicted realistically and doing the unglamorous work of helping renovate an apartment. So the Salon overlooked the artist’s skillful rendering of the workers’ musculature and the wood shavings piled up around the room as a result of their labor. His two nude paintings, placed opposite each other in the Kimbell gallery, also buck the time’s artistic conventions. His bather is a man instead of the traditional woman, caught in the act of vigorously drying himself off. Meanwhile, his nude woman is much thinner than an 1880s audience would have found attractive, and she’s covering her eyes in what seems like exhaustion rather than looking at the viewer.

The Impressionists accepted Caillebotte as one of their own despite sharing neither his schooling nor his interest in deep focus and composition. His view of the “Rue de Halévy” is close to Monet in its treatment of mist, and his “The Boulevard Seen from Above” offers a highly unusual view from directly above the street.

Paris was Caillebotte’s great subject, the inspiration for his energetic paintings of urban life. You can feel his enthusiasm for the colors and textures of fabric in his “Interior, a Woman Reading,” with its bizarre perspective. His “Fruit Displayed on a Stand” isn’t a meticulously arranged still life but rather seems to catch the figs, grapes, oranges, and tomatoes as a grocer might have put them out for sale. The celebration of nature’s bounty available to city-dwellers reminds you of American artists from the mid-20th century reveling in a consumerist paradise. In fact, Caillebotte’s “Pastry Cakes” normally hangs in a private collection next to a similar Wayne Thiebaud painting.

The artist eventually decamped for the countryside, and his landscape studies are exercises in repetition, like Monet’s haystacks, though not nearly as artistically important. Caillebotte loved sailing, and his best work from this late period seems to be inspired by water. The “Regatta in Argenteuil” is a brilliant portrait of the sun reflecting off the Seine’s surface where the artist can be seen taking out his boat. Meanwhile, the “Bridge at Argenteuil” achieves a Canaletto-like clarity, and the flowers in his “Sunflowers, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers” bear a remarkable resemblance to the sunflowers painted by van Gogh. Connecting Caillebotte to the art around him is an important achievement of this show.

There’s a bigger one, though, and it can found in the fact that nobody in his paintings is smiling. Not even Paul Hugot, whose portrait finds him dressed in the latest fashions to go out, looks all that happy at the prospect of an evening in the great city. Contrast this with Renoir’s jolly Parisians. Ambivalence creeps into the artist’s still lifes like the “Calf in Butcher Shop,” a carcass decorated with flowers that seem outrageously fake. “Paris Street; Rainy Day” was considered to be a critique of the new Paris, with its impersonal buildings and wide streets. In paintings depicting more than one person, the people never seem to be interacting with one another. Even his “Luncheon,” a portrait of the artist’s mother, brother, and family butler, has a funereal tone, with the mother still wearing black from being widowed two years before. With an empty place setting conspicuously in front of the viewer, the painting evokes loss and loneliness. The alienation of urban life in Caillebotte’s work presages Edward Hopper, and it makes this 19th-century artist who was so tied to his time and place seem startlingly modern.

[box_info]Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye

Thru Feb 14. Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. $14-18.

817-332-8451.[/box_info]