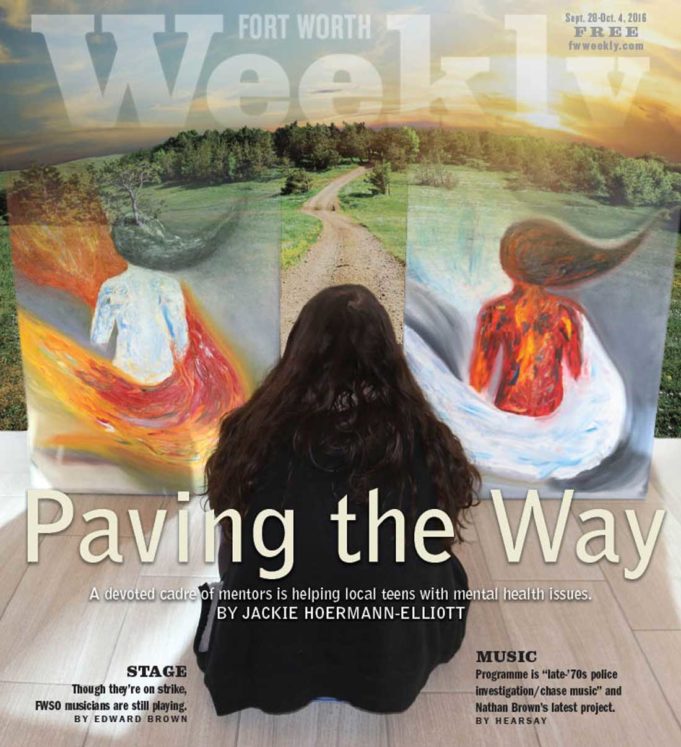

There’s a 17-year-old boy in foster care whom Jackie Davis visits almost every week. Davis is the boy’s mentor and, unquestionably, his friend. Recently, as the 31-year-old Dallas native and I sat in a plain office space near the Chisholm Trail Parkway to discuss the boy and others like him, between us rested the assumption that the child struggles with a mental illness. Instead of prying for details about his diagnosis, however, I studied the incandescence with which Davis described the brilliance of the boy’s artwork. Every finger bolted forward to punctuate the intensity of the abstract-expressionist paintings he produces.

“His work is a lot of his life stories,” Davis said, “and a lot of dreams about what he wants out of life.”

Davis remembers being as expressive as this young man when he was in foster care in Dallas in the 1980s. At 18 months old, Davis, with his three siblings, was removed from their home –– Child Protective Services had reason to suspect physical and sexual abuse. In 1985, Davis became Case No. 85-927-W304, moving from one abusive home to the next until a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) named Molly saw him not as a problem child but a child in need of a solution. After Davis met his CASA, his life took a resplendent turn.

Davis now works as one of four Youth Transition Specialists for Paving the Way (PtW), a four-year federally funded program administered by MHMR of Tarrant County. At PtW, Davis supports dozens of young adults between the ages of 16 and 21 who are transitioning to adulthood. Many of them come from foster care — like the young artist whose work Davis admires — and some come from seemingly stable home environments. The one criterion that unites all of the children is a mental health diagnosis: depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorders related to traumatic or stressful experiences that unraveled their lives in their earliest years.

Davis attributes his success to the support he received from his CASA.

“I know that for these youth this is a good thing,” he said. “At Paving the Way, we get to support them every week, and it means a lot to them, and I know it means a lot to me.”

Surviving Foster Care

In Texas, the quality of care for these children has grown grim. Gov. Greg Abbott recently urged state lawmakers to correct the deplorable conditions of foster care systems in the state, which he deemed “completely unacceptable.” Turn the calendar back to March 25, 2016, when three children had died in placement homes, and Abbott’s response was to crack down on the screening of caretakers appointed by the parents of children taken into care systems. Abbott’s well-intentioned solution flooded long-term care facilities past capacity.

Children needing to be placed in psychological treatment centers weren’t faring much better. In one case, 16 boys and girls were reported to be living in a care facility without beds. CPS workers responded by converting their offices into makeshift bedrooms, but making space for these children to sleep is only part of the problem. Helping them find headspace to cope with old traumas in new living conditions troubles many foster care children and care workers because mental stability is so difficult to see.

What’s worse is when a child’s mental health declines during or after he or she has transitioned out of the care system. According to the most recent Adoption and Foster Care Analysis report published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, an estimated 22,000 children aged out of foster care without finding a family in 2014. At that time, more than 415,000 children were reported to be living in the foster care system. The average age was 8.7 years old with slightly more boys (52 percent) than girls (48 percent).

Research on the mental health of foster children remains severely limited. In the early 2000s, several foster-care alumni groups partnered to conduct the Casey National Alumni Study. Researchers tracked the mental health diagnoses of more than 1,000 adults who had exited the foster care system, finding rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in these adults to be nearly five times the national average. Rates were also higher for panic disorders, depression, social phobias, generalized anxiety, and alcohol and drug dependence.

The effects of these diagnoses were studied in more depth in 2010, when the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago followed more than 600 foster care children transitioning out of a system. Almost 25 percent of the study’s participants experienced homelessness upon their exit. Sixty percent had been convicted of a crime within less than a decade of leaving foster care, and only 6 percent had obtained a two-year or four-year college degree by the age of 24.

The young artist Davis raves about had been in foster care for six years, having been kicked out of his home for drug use and undisclosed behavior problems. Much in the same way that that CASA advocate saw Davis as a child in need of a solution, Davis saw his client as both in need of a solution and as the solution himself.

“From day one, he was very motivated to be successful,” Davis said. “That was his big thing: He wants to be successful and be an entrepreneur like his father. But sometimes he feels like the world is against him.”

It didn’t take long to see why. One of Davis’ earliest meetings with this client involved a trip to the Department of Motor Vehicles for an identification card, without which the young man couldn’t enroll in a GED program. After four failed attempts and with little to no help from his CPS caseworker, Davis helped his client collect the necessary documents for application and accompanied him to the DMV.

On each trip, the duo waited for hours, sitting in the lobby doing not much more than “just talking,” Davis said, about their experiences in and out of care systems.

On the fourth visit, approval was granted. “The relief on his face was to die for,” laughed Davis. “And after he got his ID he got his glasses fixed, and from there everything kind of started falling into place for him, and it felt like it changed the dynamics of our relationship.”

Davis, never one to take much credit, made visible what case workers couldn’t see: potential. His faculties for discerning such potential may stem from traumas no child should ever know.