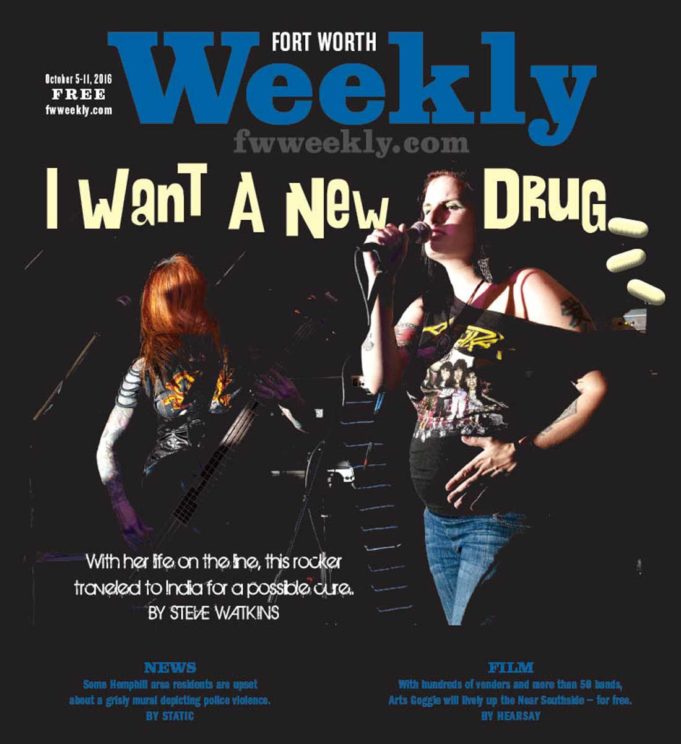

In 2011 at the recently shuttered TCU-area dive bar The Cellar, Elle Hurley did what she had done dozens of times before: She took the stage with her angry-rock band the Transistor Tramps. The sight of her, though, was surreal. The heavily tattooed singer was seven months pregnant.

The cramped, smoky space overflowed with about 100 folks, there to check out the Tramps before Hurley went on maternity leave and also the other band on the bill, headliners Pinkish Black. At one point during the latter’s obscenely loud set, Hurley’s unborn child jumped. Hurley got back onstage, grabbed the microphone, and yelled, “Pinkish Black rocks my fetus!”

The crowd went wild.

Elle Hurley was the embodiment of rock ’n’ roll. Unbeknownst to anyone there, this would be the last time the Tramps would perform.

Hurley was hiding a serious illness onstage. She had recently been diagnosed with hepatitis C. The battle with the chronic and potentially fatal disease would change her life forever, and it would lead her and her family on a journey through bureaucratic nightmares and depression and finally to India and salvation.

Hurley, who worked as a retail manager when not onstage, was diagnosed during routine bloodwork for her pregnancy.

“It was definitely a shock,” Hurley said. “I was on my way to build one of my stores on [I-35] with a team full of employees in my car when the doctor’s office called and gave me the news. So I’m sitting there, and I’m driving, [and] they tell me this, and I’m just like ‘Oh, I’m positive for what?’ Nobody in the car was able to hear what was going on. I was able to keep it private. But I was just like, ‘I really can’t talk right now. Let me call you back.’ I drove my employees to work, and when they were out of earshot, I called my husband in tears, explaining to him what the doctors told me. “

Hepatitis is a disease caused by the HCV virus, and it attacks the liver. Sufferers often need a liver transplant at some point, and at the time of Hurley’s diagnosis, there was no effective cure. Patients were given medication with some onerous side effects, and many died. The disease is passed by blood-to-blood contact and has been stigmatized. Often it is a result of intravenous drug use. For Hurley, this was a mystery. While she had been an IV drug user in her teens, she had been clean for more than 20 years. Her husband, guitarist Richard Hurley, and her older daughter were both tested and came back clean, and Hurley had been tested during her first pregnancy –– nothing. It was suggested to her at one point that this could have been the result of a tattoo, but when I contacted The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, they said that was unlikely.

“Studies show no definitive evidence for an increased risk of hepatitis C infection when tattoos were received in professional parlors,” said Dr. Scott Holmberg, chief of the Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch in CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis. “Nor is the CDC aware of any hepatitis C infections linked to a commercial tattoo parlor. However, receiving non-commercial tattoos — that is, those applied by friends or in settings such as prisons, homes, or other unregulated and unsterile conditions — might transmit HCV. Any percutaneous exposure has the potential for transferring infectious blood and potentially transmitting blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis C.”

Most professional tattoo parlors use an autoclave to sterilize their equipment, the same method used to sterilize doctor’s instruments for surgery. The CDC states that the virus could not survive an autoclave. Although heavily tattooed, Hurley has always been careful about where she got her artwork done. The source of the disease remained a mystery, but getting well was the only thing that mattered.

*****

Meanwhile, 9,000 miles away in Australia, Greg Jefferys was facing a similar predicament. At 60 years old, he had fallen ill, and when lab work came back he was also found to be suffering from hepatitis C. Like Hurley, he was an IV drug user in his youth, but now after more than 40 years clean he was testing positive for hepatitis C. He was told by the staff at the hepatitis clinic in Tasmania that it is possible for hepatitis to lie dormant for as long as 40 years. The CDC confirms that it is possible for the virus to not show up in testing. He started looking for treatment options, and he found that a new drug that could cure him was in trials. While his attempts at being included in the trials failed, there was hope that he could get the drug once it was on the market.

Back in Texas, Hurley was in limbo. Nothing could be done while she was pregnant, for fear of harming the baby.

Precautions were taken during the delivery to prevent the spread of the virus to the baby and hospital staff, and Hurley’s new daughter was born with a clean bill of health. But Hurley was already feeling rundown and sick. She was sleeping a lot, and depression and hopelessness set in. There were trials for the same medication in Texas as well.

“I did immediately start seeing a specialist,” she said. “There was research, and they were getting ready to release a drug. I knew when I got diagnosed there was a chance I would be able to fight it –– I still felt like I was handed a death sentence. But there was like this underlying ‘Maybe there’s a chance they will have this drug come out.’ ”