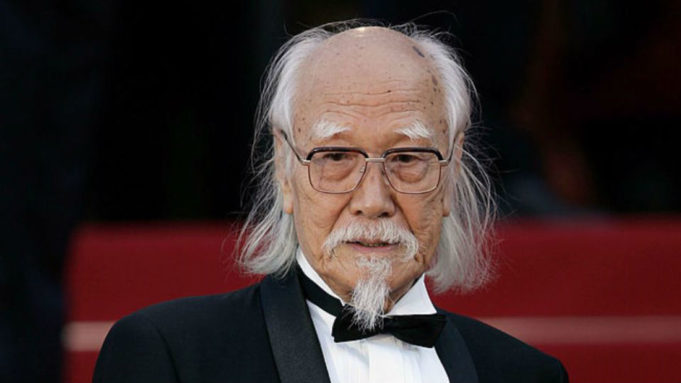

One of the giants of Japanese cinema passed away last week. The news has only now come filtering to us from Tokyo that Seijun Suzuki died on Feb. 13 at the age of 93.

If you’ve never heard of him, that’s okay. He wanted to be one of the greats in the mold of Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujirō Ozu, and Akira Kurosawa, but fate had something different planned for him. He was born in 1923 and was studying agriculture before being drafted into the Japanese army. His World War II action consisted mostly of being shipwrecked, as American forces sank two boats that he was on. He saw lots of death during his time in the war and found it all quite funny, saying that he burst into giggles as he was thrown into the sea from a ship that was being bombed. His movies are famous for their black humor, and apparently, it was in the man’s system.

After the war, he failed to get back into college (he was quite a poor student) and started working in the film industry. In 1956, he caught on at Nikkatsu Studios, one of Japan’s major filmmaking outfits, where he directed a number of financially successful, if conventional, samurai films and gangster movies. He wanted to direct the studio’s prestige pictures, but he was blocked by Shôhei Imamura, a talented filmmaker in his own right who got the studio’s plum assignments like Endless Desire and The Insect Woman. Suzuki managed to get one of those A-list projects in 1964’s Gate of Flesh and won good reviews as well as making a tidy profit for the studio, but even then it didn’t lead to anything. That’s when Suzuki started acting out, inserting flamboyant stylistic touches into his generic stories: extreme camera angles, jarring scene transitions, unexplained changes of weather and setting. This process started in early films like Youth of the Beast and Tattooed Life, but it accelerated sharply after 1964. The movies of his that you’re most likely to find are two of the last he did for Nikkatsu, Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill, and they represent High Suzuki.

His 1966 gangster movie Tokyo Drifter is the story of an antihero named Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari) who’s trying to go straight along with his boss (Ryūji Kita), and it features one character who has an office where every single object is purple. Tetsu spends most of the movie wearing a powder-blue suit and tie, but in the final shootout, it changes to all-white. In fact, the room where that shootout takes place is completely white, and the only furniture in it is a piano and a hideous statue of an emaciated, naked woman holding what looks like a giant Life Savers candy above her head. The decor is so outrageous that the movie feels like a musical, and indeed, Tetsu expresses his sense of alienation by spontaneously bursting into his personal theme song from time to time. At one point, his singing gives away his position to his enemies, but he kills them anyway. The shootouts defy all laws of physics, and if Tetsu throws his gun on the floor at your feet, you know that five seconds later, he’ll use it to kill you. Tetsu gets sold out by everyone eventually, and the movie’s distrust of institutions and its hallucinatory visual style resonated with young Japanese people in the late ’60s, who saw their country being sold out to large corporations. Watching it now, you’ll see a lot of this movie’s influence in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, especially in the Bride’s face-off with O-Ren Ishii in the Japanese nightclub.

If Tokyo Drifter is hallucinatory, then Branded to Kill from the following year is downright schizophrenic. Here, the main character is a hit man named Gorô Hanada (Jô Shishido), who becomes sexually aroused whenever he smells cooking rice and is ranked as Japan’s Number 3 killer. Who compiles the rankings and what criteria do they use? We never find out, but Gorô botches a hit when a butterfly lands on the scope of his sniper rifle just as he pulls the trigger. After that, he becomes a target for the other killers, and Killer No. 1 (Kôji Nanbara) issues Gorô a face-to-face death threat — and then promptly moves in with him! Gorô makes a getaway after one murder by jumping out a window onto a passing blimp, and kills someone else by shooting him through the drain in his sink. (Jim Jarmusch would later steal this bit for his 2000 movie Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai.) The pace of the visuals is frenetic, and every death scene (of which there are many) is memorable in some way. Cinematic violence has only been as beautiful in a few movies; I think of The Godfather, L.A. Confidential, and some of Tarantino’s best work. The Criterion Collection DVD of this movie has a juicy interview with Shishido, where he reveals that Suzuki was nicknamed “Dirty Seijun,” because when he was shooting a film, he’d get so wrapped up in the process that he’d stop bathing or changing his clothes. Shishido also wishes for a bigger penis in the interview and pulls a fake gun on the film crew.

Branded to Kill was the last straw for Nikkatsu president Kyusaku Hori. Finding Suzuki’s movies incomprehensible, he fired the director. This occasioned protests by Suzuki’s fans and a successful wrongful-termination lawsuit, but Suzuki was blackballed by the Japanese movie studios for a decade. He came back to prominence in the late 1970s with his independently made, award-winning trilogy of ghost stories (Zigeunerweisen, The Heat-Haze Theater, and Yumeji), and an international audience started to groove to his avant-garde stylings with the advent of home video. Suzuki continued to act occasionally and make films, including 2001’s Pistol Opera (a loose sequel to Branded to Kill) and 2005’s Princess Raccoon, a charming musical that mostly takes place on a bare soundstage and stars Zhang Ziyi, speaking her part in her native Chinese. This was Suzuki’s last film as a director, and though it never got released in American theaters, it’s well worth seeking out on disc.

In the end, Suzuki wound up accidentally on purpose catching the mood of his time. His absurdist movies capture the disenchantment that Japanese moviegoers felt with their society, and his formal experiments reflect what contemporaries like Nagisa Oshima, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Masahiro Shinoda, and Kaneto Shindô were doing in their films that drew attention to their artificiality rather than obeying the established classical, invisible style. His colleagues were remarkable filmmakers, but none of them went as far as Suzuki, the provocateur who lived long enough to see his best work honored by the world.